Healthcare in Austria

The nation of Austria has a two-tier health care system in which virtually all individuals receive publicly funded care, but they also have the option to purchase supplementary private health insurance. Care involving private insurance plans (sometimes referred to as "comfort class" care) can include more flexible visiting hours and private rooms and doctors.[1] Some individuals choose to completely pay for their care privately.[1]

Healthcare in Austria is universal for residents of Austria as well as those from other EU countries.[2] Students from an EU/EEA country or Switzerland with national health insurance in their home country can use the European Health Insurance Card.[3] Self-insured students have to pay an insurance fee of EUR 52.68 per month.[3]

Enrollment in the public health care system is generally automatic and is linked to employment,[4] however insurance is also guaranteed to co-insured persons (i.e. spouses and dependents ), pensioners, students, the disabled, and those receiving unemployment benefits.[5] Enrollment is compulsory, and it is not possible to cross-shop the various social security institutions.[4] Employers register their employees with the correct institution and deduct the health insurance tax from employees' salaries.[6] Some people, such as the self-employed, are not automatically enrolled but are eligible to enroll in the public health insurance scheme.[4] The cost of public insurance is based on income and is not related to individual medical history or risk factors.[6]

All insured persons are issued an e-Card, which must be presented when visiting a doctor (however some doctors only treat privately insured patients). The e-Card allows for the digitization of health claims and replaces the earlier health insurance voucher.[7] Additionally the e-Card can be used for electronic signatures.[8] E-Cards issued after October 2019 will also contain a photo of the card owner to prevent fraud. [9]

Hospitals and clinics can be either state-run or privately run.[4] Austria has a relatively high density of hospitals and physicians; In 2011 there were 4.7 Physicians per 1000 people, which is slightly greater than the average for Europe.[4] In-patient care is emphasized within the Austrian healthcare system; Austria has the most acute care discharges per 100 inhabitants in Europe and the average hospital stay is 6.6 days compared with an EU average of 6.[4]

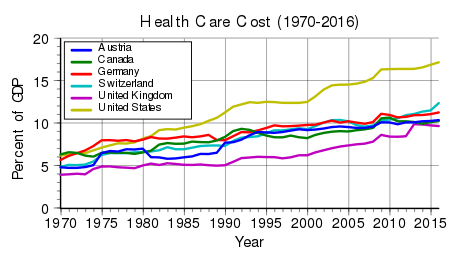

By 2008 the economic crisis caused a deep recession, and out-of-pocket payments for healthcare increased to become 28% of health expenditures.[10] By 2010, Austria's public spending has decreased overall, but it was 15.5%, compared to 13.9% fifteen years earlier.[11]

International comparisons

Austria's health care system was given 9th place by the World Health Organization (WHO) in their mid-2000s (decade) international ranking.[1] In 2015 the cost of healthcare was 11.2% of GDP -the fifth highest in Europe.[12]

The city of Vienna has been listed as 1st in quality of living (which includes a variety of social services) by the Mercer Consultants.[1]

In a sample of 13 developed countries Austria was 5th in its population weighted usage of medication in 14 classes in 2009 and fourth 2013. The drugs studied were selected on the basis that the conditions treated had high incidence, prevalence and/or mortality, caused significant long-term morbidity and incurred high levels of expenditure and significant developments in prevention or treatment had been made in the last 10 years. The study noted considerable difficulties in cross border comparison of medication use.[13]

It was placed 12th in Europe by the Euro health consumer index in 2015. The fact that abortion is not carried out in the public healthcare system reduced its rank.[14]

Waiting times

Despite government claims that no noteworthy waits exist (2007), medium or long waits are normal for at least some elective surgery. Hospital organizations in 2005 stated that mean hip and knee replacement wait times range from 1–12 months, but are generally 3–6 months. In Styria and Upper Austria mean hip replacement wait times were 108 days (about 3.5 months) and mean knee replacement 172 days (5.5 months), cor cataract surgery 142 days (4 months 20 days). For Upper Austria they were 10.3 weeks (72 days, 2 months 11 days) 21.3 weeks (149 days, almost 5 months) and 12 weeks (84 days, or 2 months 23 days). A survey by Statistik Austria found an average wait time of 102 days for eye lens surgery, 78 days (2.5 months) for hip joint surgery, 97 days (3 months 5–5 days) for knee joint surgery, 39 days (1 month 8- days) for coronary surgery, and 28 days (4 weeks) for cardiac surgery [15]

Waiting times can be shortened by arranging to visit the same hospital doctor in a private hospital or clinic. Waits are also sometimes illegally shortened in return for legal or illegal additional payments. Hospital doctors also receive additional fees to treat privately insured patients even though they are only supposed to receive better amenities/accommodations. They may therefore treat private patients sooner.[16] Two Austrian health insurance companies advertised low wait times on their web sites. In a survey in Lower Austria, 8% of respondents said that they were offered shorter waiting times for additional private payments.[15] According to Statistics Austria, 2007, in Thomson & Mossialos, 2009, as cited in Health Systems in Transition (HiT) profile of Austria, 2013, social health insurance patients waited twice as long for cardiac catheterization, and 3-4 times as long for cataract and knee surgery. Compared to individuals with private supplementary insurance, those covered by statutory health insurance wait from three to four times as long for cataract operations and knee operations. For cardiac catheterization procedures, statutory insurance patients wait twice as long. Some states have created objective waiting list guidelines to counteract this.[11]

History

Austria’s health care system was developed alongside other social welfare programs by the Social Democratic Party of Austria in Vienna (during its classical 'Red Vienna' period) initially.[17]

Austria's health care began primarily in 1956 with the "Allgemeines Sozialversicherungsgesetz" better referred to as the General Social Insurance Law or ASVG, which mandated that healthcare is a right.[18] Individuals become eligible, and automatically registered for healthcare, upon employment.[5] The individual get included into the insurance fund known as Krankenkasse, which results in you receiving an insurance card that covers not only the healthcare, but pensions, and unemployment as well. The level of coverage rapidly grew since 1955-1956 ratification of the General Social Insurance Law, and by 1980 it included unrestricted hospital care, and preventive check-up.[11]

In 2010 under the Chancellorship of Werner Faymann, the Social Democratic Health Minister Alois Stöger began the process of reform as a response to rising healthcare costs and difficulties with capacity. The system is financed in part with public debt which had become a significant challenge in the aftermath of the recession which hit Austria in 2009. The reforms for 2013 aimed to increase capacity, improve the quality of care, and address fiscal concerns in concert with the Finance Ministry.[19] A key outcome of the reform with the introduction of a budget cap on healthcare expenditure.[19] The idea of structural reform was not entertained. Because of the federal structure of Austria the legal structure of the social security programme is unusually complex with multiple entities at the state level under the umbrella of the national institution: making adjustments to the federal framework would present a constitutional issue.[19]

Structure

Austria's health programs are funded by the sickness insurance fund known as the Krankenkasse, which in 2013 took 11.0% of the GDP, which was above the average of the E.U average of 7.8% of GDP.[20] Austria's healthcare system is decentralized, and operates with a system similar to United States federalism. Each of the nine states and the federal government of Austria have legal limitation and roles in their healthcare system. Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs is the federal aspect, its role is to develop the framework for the services that are offered, and handle the sickness insurance fund known as the Krankenkasse, which funds Austria's healthcare system. The role of the Provinces is to manage and provide the care as needed.[18] The provision of healthcare is ultimately carried out jointly by federal, provincial, and local actors.[4] Since Austria's health program covers a vast array of social insurance including but not limited to unemployment insurance, family benefits, accident insurance, the overall bureaucracy is vast. While the Krankenkasse is the primary fund, Austria social protection network actually implemented by 22 smaller funds, 19 of which are purely for sickness and all of which by public law are self-governed in order to insure decentralization. The funds are also differentiated to allow for effective risk pooling, which is why membership is compulsory and citizens are generally unable to select which fund they will belong to.[4]

Electronic health records

.jpg)

In December 2012 Austria introduced an Electronic Health Records Act (EHR-Act).[21] These provisions are the legal foundation for a national EHR system based upon a substantial public interest according to Art 8(4) of the Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC.[22]

The Austrian EHR-Act pursues an opt-out approach in order to harmonize the interests of public health and privacy in the best possible manner.

The 4th Part of the Austrian Health Telematics Act 2012 (HTA 2012) – these are the EHR provisions – are one of the most detailed data protection rules within Austrian legislation. Numerous safeguards according to Art 8(4) DPD guarantee a high level of data protection. For example:

- personal health data needs to be encrypted prior to transmission (§ 6 HTA 2012), or

- strict rules on data usage allow personal health data only to be used for treatment purposes or exercising patients' rights (§ 14 HTA 2012), or

- patients may declare their right to opt out from the national EHR at any time (§ 15 HTA 2012), or

- the implementation of an EHR-Ombudsman, to support the patients in exercising their rights (§ 17 HTA 2012), or

- the Access Control Center provides EHR-participants with full control over their data (§ 21 HTA 2012), or

- judicial penalties for privacy breaches (Art 7 of the EHR-Act).

References

- Bondi, Susie (September 2009). "Austrian Health Care". Association of Americans Resident Overseas. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- The Austrian healthcare system Overview of how it works Accessed: 16 October 2011.

- Austrian agency for international mobility and cooperation in education, science and research: National health insurance Archived 2014-12-29 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: June 26, 2014.

- "The Austrian Healthcare System: Key Facts" (PDF). Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "Health Insurance". Stadt Wien. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "Healthcare in Austria". Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "E-Card als Bürgerkarte". Digitales Österreich. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "Pressegespräch - Jetzt kommt die e-cardmit Foto". Chipkarte.at. 2 October 2019.

- "Expenditure on health care". European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. 2011.

- Hofmarcher, Maria M. (2013). Quentin, Wilm (ed.). "Austria: health system review" (PDF). Health Systems in Transition. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization. 15 (7): 75–134. PMID 24334772.

- Ballas, Dimitris; Dorling, Danny; Hennig, Benjamin (2017). The Human Atlas of Europe. Bristol: Policy Press. p. 79. ISBN 9781447313540.

- Office of health Economics. "International Comparison of Medicines Usage: Quantitative Analysis" (PDF). Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- "Outcomes in EHCI 2015" (PDF). Health Consumer Powerhouse. 26 January 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Czypionka, Thomas; Kraus, Markus; Riedel, Monika; Röhrling, Gerald (2007). Waiting Times for Elective operations in Austria: a Question of Transparency (PDF) (Report). Vienna: Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS). pp. 1–3, 5–9, 11, 18.

- Stepan, Adolf; Sommersguter‐Reichmann, Margit (2005). "Monitoring political decision‐making and its impact in Austria". Health Economics. 14 (Suppl 1): S7–S23. doi:10.1002/hec.1026. PMID 16161199.

- Austria. European Observatory on Health Care Systems

- "The Health care Systems of the Individual Member States" (PDF). European Parliament. 1998.

- Hofmarcher, Maria (Oct 2014). "The Austrian health reform 2013 is promising but requires continuous political ambition". Health Policy. 118 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.09.001. PMID 25239031.

- "Austria Health Care & Long-Term Care Systems" (PDF). European Commission. 2016.

- Electronic Health Records Act (EHR-Act)

- Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC