Mycosis

Mycosis is a fungal infection of animals, including humans.[1] Mycoses are common and a variety of environmental and physiological conditions can contribute to the development of fungal diseases. Inhalation of fungal spores or localized colonization of the skin may initiate persistent infections; therefore, mycoses often start in the lungs or on the skin.[2]

| Mycosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Plural: mycoses |

| |

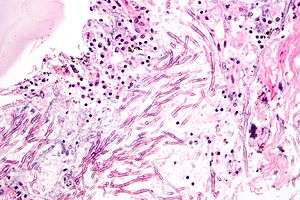

| Micrograph showing a mycosis (aspergillosis). The Aspergillus (which is spaghetti-like) is seen in the center and surrounded by inflammatory cells and necrotic debris. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

Fungal infections of the skin was the 4th most common skin disease in 2010 affecting 984 million people.[3] An estimated 1.6 million people die each year of fungal infections.[4]

Causes

Individuals being treated with antibiotics are at higher risk of fungal infections.[5]

People with weakened immune systems are also at risk of developing fungal infections. This is the case of people with HIV/AIDS, people under steroid treatments, and people taking chemotherapy. People with diabetes also tend to develop fungal infections.[6] Very young and very old people, also, are groups at risk.[7] Although all are at risk of developing fungal infections, the likelihood is higher in these groups.

Children whose immune system is not functioning properly (such as children with cancer) are at risk of invasive fungal infections. Antifungal medications can be given at the development of a fever or when an infection has been formally identified. These agents appear equally efficacious.[8] Research suggests kidney damage was less likely with a lipid preparation of amphotericin B compared with conventional amphotericin B. No significant differences were observed in children when comparing other antifungal agents.

Diagnosis

Classification

Mycoses are classified according to the tissue levels initially colonized.

Superficial mycoses

Superficial mycoses are limited to the outermost layers of the skin and hair.[9]

An example of such a fungal infection is Tinea versicolor, a fungus infection that commonly affects the skin of young people, especially the chest, back, and upper arms and legs. Tinea versicolor is caused by a fungus that lives in the skin of some adults. It does not usually affect the face. This fungus produces spots that are either lighter than the skin or a reddish brown.[10] This fungus exists in two forms, one of them causing visible spots. Factors that can cause the fungus to become more visible include high humidity, as well as immune or hormone abnormalities. However, almost all people with this very common condition are healthy.

Cutaneous mycoses

Cutaneous mycoses extend deeper into the epidermis, and also include invasive hair and nail diseases. These diseases are restricted to the keratinized layers of the skin, hair, and nails. Unlike the superficial mycoses, host immune responses may be evoked resulting in pathologic changes expressed in the deeper layers of the skin. The organisms that cause these diseases are called dermatophytes, the resulting diseases are often called ringworm, dermatophytosis or tinea. Dermatophytes only cause infections of the skin, hair, and nails, and are unable to induce systemic, generalized mycoses, even in immunocompromised hosts.[11]

Subcutaneous mycoses

Subcutaneous mycoses involve the dermis, subcutaneous tissues, muscle and fascia. These infections are chronic and can be initiated by piercing trauma to the skin which allows the fungi to enter. These infections are difficult to treat and may require surgical interventions such as debridement.

Systemic mycoses due to primary pathogens

Systemic mycoses due to primary pathogens originate primarily in the lungs and may spread to many organ systems. Organisms that cause systemic mycoses are inherently virulent. In general, primary pathogens that cause systemic mycoses are dimorphic.

Systemic mycoses due to opportunistic pathogens

Systemic mycoses due to opportunistic pathogens are infections of patients with immune deficiencies who would otherwise not be infected. Examples of immunocompromised conditions include AIDS, alteration of normal flora by antibiotics, immunosuppressive therapy, and metastatic cancer. Examples of opportunistic mycoses include Candidiasis, Cryptococcosis and Aspergillosis.

Prevention

Keeping the skin clean and dry, as well as maintaining good hygiene, will help larger topical mycoses. Because fungal infections are contagious, it is important to wash after touching other people or animals. Sports clothing should also be washed after use.

Treatment

Topical and systemic antifungal drugs are used to treat mycoses.

Epidemiology

Fungal infections of the skin were the 4th most common skin disease in 2010 affecting 984 million people.[3]

An estimated 1.6 million people die each year of fungal infections.[4]

See also

- Pathogenic fungi

- Fungal infection in plants § Fungi

- Actinomycosis

- Blastomycosis

- Coccidioidomycosis

- Mucormycosis

- Onychomycosis

- Zygomycosis

References

- "Dorlands Medical Dictionary:mycosis".

- "What Is a Fungal Infection?". Archived from the original on June 19, 2009. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- Hay, Roderick J.; Johns, Nicole E.; Williams, Hywel C.; Bolliger, Ian W.; Dellavalle, Robert P.; Margolis, David J.; Marks, Robin; Naldi, Luigi; Weinstock, Martin A.; Wulf, Sarah K.; Michaud, Catherine; Murray, Christopher J.L.; Naghavi, Mohsen (Oct 28, 2013). "The Global Burden of Skin Disease in 2010: An Analysis of the Prevalence and Impact of Skin Conditions". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 134 (6): 1527–34. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.446. PMID 24166134.

- "Stop neglecting fungi". Nature Microbiology. 2 (8): 17120. 25 July 2017. doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.120. ISSN 2058-5276. PMID 28741610.

- Britt, L. D.; Peitzman, Andrew; Barie, Phillip; Jurkovich, Gregory (2012). Acute Care Surgery. p. 186. ISBN 9781451153934.

- "Thrush in Men". NHS. Retrieved 2013-07-13.

- "Fungal infections: Introduction". Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- Blyth, Christopher C; Hale, Katherine; Palasanthiran, Pamela; O'Brien, Tracey; Bennett, Michael H (2010-02-17). "Antifungal therapy in infants and children with proven, probable or suspected invasive fungal infections". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD006343. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006343.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMID 20166083.

- Malcolm D. Richardson; David W. Warnock (2003). "Introduction". Fungal Infection: Diagnosis and Management. John Wiley & Sons, 2012. p. 5.

- "Tinea versicolor" (PDF). Royal Berkshire NHS. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 20, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- Schmidt, Axel; Geschke, Frank-Ulrich (2007), "Antimycotics", Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (7th ed.), doi:10.1002/14356007.a03_077, ISBN 978-3527306732

External links

- Guide to Fungal Infections – patient-oriented, educational website written by dermatologists

| Classification |

|---|