Tinea nigra

Tinea nigra, also known as superficial phaeohyphomycosis[1] and Tinea nigra palmaris et plantaris,[1] is a superficial fungal infection that causes dark brown to black, painless patches called macules on the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet of otherwise healthy individuals. The macules occasionally extend to the fingers, toes, and nails, and may be reported on the chest, neck, or genital area.[2]:311 Tinea nigra infections can present with multiple macules that can be mottled or velvety in appearance, and may be oval or irregular in shape. The macules can be anywhere from a few mm to several cm in size.[3]

| Tinea nigra | |

|---|---|

| |

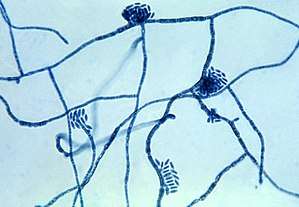

| Micrograph of the fungus Hortaea werneckii, the causative agent of tinea nigra | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

Causes

This infection is caused by the fungus formerly classified as Exophiala werneckii, but more recently classified as Hortaea werneckii.[4] The causative organism has also been described as Phaeoannellomyces werneckii.[5] Tinea nigra is extremely superficial and can be removed from the skin by forceful scraping. It tends to appear in areas where eccrine sweat glands are highly concentrated. Infections generally start to appear on the skin around 2–7 weeks post inoculation. The ability of H. werneckii to tolerate high salt concentrations and acidic conditions allows it to flourish inside the stratum corneum. H. wernickii tends remain localized in one spot or region, and produces darkly-colored, brown macules on the skin due to the production of a melanin-like substance.[3]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of tinea nigra is made based on microscopic examination of stratum corneum skin scrapings obtained by using a scalpel. The scrapings are mixed with potassium hydroxide (KOH).[6] The KOH lyses the nonfungal debris.[6] The skin scrapings are cultured on Sabouraud's agar at 25°C and allowed to grow for about a week. H. werneckii can generally be distinguished due to its two-celled yeast form and the presence of septate hyphae with thick, darkly pigmented walls.[3]

Treatment

Treatment consists of topical application of dandruff shampoo, which contains selenium sulfide, over the skin. Topical antifungal imidazoles such as ketoconazole, itraconazole, and miconazole may also be used. Imidazoles are generally used twice daily for a two-week period. This is the same treatment plan for tinea or pityriasis versicolor. Other treatment methods include the use of epidermal tape stripping, Undecylenic acid, and other topical agents such as ciclopirox. Once a tinea nigra infection has been eradicated from the host, it is not likely to reoccur.[3]

Epidemiology

Tinea nigra is commonly found in Africa, Asia, Central America, and South America. It is typically not found in the United States or Europe, although cases have been documented in the Southeastern United States. People of all ages can be infected; however, it is generally more apparent in children and younger adults. Females are three times more likely than males to become infected.[3]

See also

- List of cutaneous conditions

References

- Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. pp. Chapter 76. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- Schwartz, Robert A (September 2004). "Superficial fungal infections". The Lancet. 364 (9440). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17107-9. PMID 15451228.

- Murray, Patrick R.; Rosenthal, Ken S.; Pfaller, Michael A. (2005). Medical Microbiology (5th ed.). Elsevier Mosby.

- Pegas JR, Criado PR, Lucena SK, de Oliveira MA (2003). "Tinea nigra: report of two cases in infants". Pediatric Dermatology. 20 (4): 315–7. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.2003.20408.x. PMID 12869152.

- Gladwin, Mark; Trattler, Bill. Clinical Microbiology (4th ed.). p. 196.