Deindustrialisation by country

Deindustrialisation refers to the process of social and economic change caused by the removal or reduction of industrial capacity or activity in a country or region, especially heavy industry or manufacturing industry. Deindustrialisation has taken place in many nations over the years, as social changes and urbanisation have changed the financial demographics of the world. Phenomena such as the mechanisation of labour render industrial societies obsolete, and lead to the de-establishment of industrial communities.

Background

Theories that predict or explain deindustrialisation have a long intellectual lineage. Karl Marx's theory of declining (industrial) profit argues that technological innovation enables more efficient means of production, resulting in increased physical productivity, i.e., a greater output of use value per unit of capital invested. In parallel, however, technological innovations replace people with machinery, and the organic composition of capital increases. Assuming only labour can produce new additional value, this greater physical output embodies a smaller value and surplus value. The average rate of industrial profit therefore declines in the longer term.

George Reisman (2002) identified inflation as a contributor to deindustrialisation. In his analysis, the process of fiat money inflation distorts the economic calculations necessary to operate capital-intensive manufacturing enterprises, and makes the investments necessary for sustaining the operations of such enterprises unprofitable.

The term de-industrialisation crisis has been used to describe the decline of labour-intensive industry in a number of countries and the flight of jobs away from cities. One example is labour-intensive manufacturing. After free-trade agreements were instituted with less developed nations in the 1980s and 1990s, labour-intensive manufacturers relocated production facilities to Third World countries with much lower wages and lower standards. In addition, technological inventions that required less manual labour, such as industrial robots, eliminated many manufacturing jobs.

Australia

In 2008, four companies mass-produced cars in Australia.[1] Mitsubishi ceased production in March 2008, followed by Ford in 2016, and Holden and Toyota in 2017.[2]

Holden bodyworks were manufactured at Elizabeth, South Australia and engines are produced at the Fishermens Bend plant in Port Melbourne, Victoria. In 2006, Holden's export revenue was just under A$1.3 billion.[3] In March 2012, Holden was given a $270 million lifeline by the Australian government. In return, Holden planned to inject over $1 billion into car manufacturing in Australia. They estimated the new investment package would return around $4 billion to the Australian economy and see GM Holden continue making cars in Australia until at least 2022.[4] However, Holden announced on 11 December 2013 that Holden cars would no longer be manufactured in Australia from the end of 2017.[5]

Ford had two main factories, both in Victoria: located in the Geelong suburb of Norlane and the northern Melbourne suburb of Broadmeadows. Both plants were closed down in October 2016.

Until 2006, Toyota had factories in Port Melbourne and Altona, Victoria. Since then, all manufacturing has been at Altona. In 2008, Toyota exported 101,668 vehicles worth $1,900 million.[6] In 2011 the figures were "59,949 units worth $1,004 million".[7] On 10 February 2014 it was announced that by the end of 2017 Toyota would cease manufacturing vehicles and engines in Australia.[8]

Until trade liberalisation in the mid 1980s, Australia had a large textile industry. This decline continued through the first decade of the 21st century. Since the 1980s, tariffs have steadily been reduced; in early 2010, the tariffs were reduced from 17.5 percent to 10 percent on clothing, and 7.5–10% to 5% for footwear and other textiles.[9] As of 2010, most textile manufacturing, even by Australian companies, is performed in Asia.

Austria

Austria has many indicators that justify labelling them as a deindustrialising country. Data collected from the OECD for Austria has shown that since 1956 total employment did grow until 1994 and since then remained relatively steady. Employment in industry and construction, however, has declined steadily as service sector employment has steadily increased. Data also shows that even as employment in industry and construction has decreased, industry productivity has continued to grow.

Austrian unemployment has steadily increased since 1983 due to deindustrialisation. Austria was one of the countries in a study that showed that increasing overall unemployment was significantly related to manufacturing unemployment. Austria's foreign and domestic policy has made deindustrialisation possible. High labour taxes and high withholding taxes repel low-skill immigration as low capital taxes enable domestic capital investment. Stern banking secrecy policies, no withholding taxes for non-residents, joining the European Union, and adopting the Euro enabled substantial growth in Austria's services sector.

Belgium

Data taken from the OECD website show that industrial employment in Belgium rose between 1999 and 2000 and then declined until 2003, rising again until 2006. The overall trend in industrial employment in Belgium, however, is still a decline. OECD data also shows that production and sales of total industry in Belgium has been on the rise since 1955, with the exception of small declines during a few years. Despite this trend, deindustrialisation is occurring at fairly rapid rates in Belgium. Variables such as large population increases and regional discrepancies account for these misleading statistics. Deindustrialisation is hitting the region of Wallonia much harder than the region of Flanders. Wallonia remains much more impoverished and has an unemployment rate of about 17% (twice that of the unemployment rate in Flanders). Other statistics displaying the effects of deindustrialisation in Belgium is the rise in employment in the service sector from 1999 until 2006. Today, industry is much less significant in Belgium than it has been in previous years.

Canada

Much of the academic literature pertaining to Canada hints at deindustrialisation as a problem in the older manufacturing areas of Ontario and the east. Nationwide, over the past fifty years, according to 2008 OECD data, industrial production and overall employment have been steadily increasing. Industrial production levelled off a bit between 2004 and 2007, but its production levels are the highest that they have ever been. The perception of deindustrialisation that the literature refers to deals with the fact that although employment and economic production have risen, the economy has shifted drastically from manufacturing jobs to service sector jobs. Only 13% of the current Canadian population has a job in the industrial sector. Technological advancements in industry over the past fifty years have allowed for industrial production to keep rising during the Canadian economic shift to the service sector. 69% of the GDP of Canada comes from the service sector.[10][11]

Denmark

Regarding Denmark's industry, the country does not appear to be deindustrialising as a whole. Literature (Goldsmith and Larsen 2004) has stated that perhaps Denmark's size and "Nordic style" of governing has allowed it to hide from the detrimental effects of globalisation. Both men's and women's labour statistics (OECD data 2008) show a steady increase over the past decade. Despite a slight dip from 2001 to 2003, overall employment in Denmark has been at a steady increase since 1995. Denmark's total industry output has also been on the rise since the 1974, despite an economic recession from 1987 to 1993. The country's high employment and low unemployment rates have improved the production industry, and the high tax rates have strengthened the economy.

Finland

Based on the data from the OECD website, Finland has been industrialising according to industrial employment and industrial production statistics. Finland has been considered very resilient based on its remarkable economic comeback after their recession in 1990 due to the fall of the Soviet Union. During this time, production of total industry and civilian employment in industry declined rapidly. Finland has been ranked number one three times in the World Economic Forum competitiveness studies as one of the most developed IT economies since 2000.

Since the 1990 recession, which was one of the largest in European history, Finland has managed to soar back to the top of the economic ladder. Finland has done so by focusing strongly on education. After their recession, Finland invested its money on boosting R&D, education, and retraining workers that had lost their job due to the recession. With its investment in education, Finland has succeeded in increasing some of its industries. For example, the forest industry now specialises in high-quality papers. As a result of investment in education and technology, Finland is now one of the world's largest producers of paper-making machinery. According to the statistics on the OECD website, Finland is not deindustrialising.

France

Data for France indicates that while employment in industry relative to the total French economy has decreased, there is a lack of sound evidence pointing to an overall trend of deindustrialisation. Research (Lee 2005, Feinstein 1999) shows that at the same time relative employment in industry is decreasing, total production in industry has almost quadrupled since the mid 20th century, levelling off only since about the year 2000 (OECD 2008). Lee shows that between 1962 and 1995, employment in industry in France fell 13.1% (2005:table 1). Advances in technology that allow for higher output by fewer employees, coupled with a change in the type of products manufactured domestically, such as the high-tech electronics now manufactured in France, explain the negative relationship of employment and output in French industry. Thus, it may feel like deindustrialisation is occurring because of the relative decrease of employment or highly publicised cases of outsourcing, yet the data suggest industry production in France is not suffering.

Germany

Historic

In occupied Germany after World War II the Morgenthau Plan was implemented, although not in its most extreme version.[12]:530 The plan was present in the U.S. occupation directive JCS 1067[13][12]:520 and in the Allied "industrial disarmament" plans.[12]:520 On February 2, 1946, a dispatch from Berlin reported:

Some progress has been made in converting Germany to an agricultural and light industry economy, said Brigadier General William H. Draper, Jr., chief of the American Economics Division, who emphasised that there was general agreement on that plan. He explained that Germany's future industrial and economic pattern was being drawn for a population of 66,500,000. On that basis, he said, the nation will need large imports of food and raw materials to maintain a minimum standard of living. General agreement, he continued, had been reached on the types of German exports — coal, coke, electrical equipment, leather goods, beer, wines, spirits, toys, musical instruments, textiles and apparel — to take the place of the heavy industrial products that formed most of Germany's pre-war exports.[14]

According to some historians, the U.S. government abandoned the Morgenthau plan as policy in September 1946 with Secretary of State James F. Byrnes' speech "Restatement of Policy on Germany".[15]

Others have argued that credit should be given to former U.S. President Herbert Hoover, who in one of his reports from Germany, dated March 18, 1947, argued for a change in occupation policy, amongst other things stating, "There is the illusion that the New Germany left after the annexations can be reduced to a 'pastoral state'. It cannot be done unless we exterminate or move 25,000,000 people out of it."[16]

Worries about the sluggish recovery of the European economy, which before the war had depended on the German industrial base, and growing Soviet influence amongst a German population subject to food shortages and economic misery, caused the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Generals Clay and Marshall to start lobbying the Truman administration for a change of policy.[17]

In July 1947, President Harry S. Truman rescinded on "national security grounds"[17] the punitive occupation directive JCS 1067, which had directed the U.S. forces of occupation in Germany to "take no steps looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany [or] designed to maintain or strengthen the German economy". It was replaced by JCS 1779, which instead noted that "[a]n orderly, prosperous Europe requires the economic contributions of a stable and productive Germany."[18]

It had taken over two months for General Clay to overcome continued resistance to the new directive JCS 1779, but on July 10, 1947, it was finally approved at a meeting of the SWNCC. The final version of the document "was purged of the most important elements of the Morgenthau plan."[19]

Dismantling of (West) German industry ended in 1951, but "industrial disarmament" lingered in restrictions on actual German steel production, and production capacity, as well as in restrictions on key industries. All remaining restrictions were finally rescinded on May 5, 1955. "The last act of the Morgenthau drama occurred on that date or when the Saar was returned to Germany."[12]:520

Vladimir Petrov concluded: "The victorious Allies … delayed by several years the economic reconstruction of the war torn continent, a reconstruction which subsequently cost the US billions of dollars."[20]

Current

In the early 2000s, the unemployment in Germany was moderately high, while industrial output was steadily increasing. Germany's unemployment rate of roughly seven percent (OECD, 2008) is by and large due to the continuing struggles with the reunification process between East and West Germany that began in 1990. However, the unemployment rate has been declining since 2005, when it reached its peak of over ten percent. In the 2010s, Germany's unemployment rate has been one of the lowest in continental Europe.

Between 2010 and 2017 the manufacturing employment in absolute terms has risen by 10% from 4.9 million workers to 5.4 million December 2016. Federal German statistics office

Indian subcontinent

During the reign of the Mughal Empire, India was estimated to be the largest economy in the world, apparently accounting for approximately one-quarter of the world economy.[21] It had strong agriculture and industry, and was the world's largest cotton textile manufacturer (particularly Bengal Subah).[22] But in the latter half of the 18th century, India underwent political turmoil and Europeans (mainly British) got an opportunity to become political masters. During their rule, British mercantilism targeted weakening of the craft guilds, pricing and quota caps, and banning production of many products and commodities in India.

India's de-industrialization contributed to Britain's Industrial Revolution, with India no longer being a competitor in the global textile industry, as well as India itself becoming a large market for British textiles. Indian cotton-making could not compete with British inventions and modernisation, such as the: Spinning Jenny, Automatic Mule, Water Frame, Power Loom, Flying Shuttle or Steam Engine until Britain greatly surpassed the estimated production of India's more basic manual industry.[23][24][25][22]

Ireland

Ireland has yet to de-industrialise. Industrial employment and production and sales in industry have increased since 1990, according to OECD data. The increase in industry coincided with the introduction of Intel to the Irish economy in late 1989. Though one may not think of Intel as industry in the same sense as steel production, it is considered to be industry. Intel is now the largest company by turnover in Ireland. This was the beginning of what was called the "Celtic Tiger" economy. Dell and Microsoft followed Intel to Ireland, creating a large software industry. As is evidenced by these three companies, a majority of the industries that exist in Ireland are a result of foreign direct investment. The top three FDIs are the US, the UK, and Germany.

Italy

Overall, Italy in 2008 did not seem to be deindustrialising. According to OECD (2008) data, the rate of industrial employment is at an all-time high, although, in general, it has stayed relatively consistent since 1956. The rate of industrial production is also on the rise after a small dip in recent years; even though production rates are still at almost 2 percent less than they were in 2000, the 2005 rate is eighty percent more than what it was in 1955. These figures, however, do not make the distinction between different regions of the country: according to Rowthorn and Ramaswamy (1999), most manufacturing plants are located in cities such as Genoa and Milan in Northern Italy, and the unemployment rate in the South is significantly higher than in the North. Prior to World War II, Italy's economy was mainly agricultural, but it has since shifted to become one of the largest industrial economies in the world. In general, Italy is continuing to experience a period of industrialisation that has been taking place since the shift.

Japan

Historic

To further remove Japan as a potential future military threat after World War II, the Far Eastern Commission decided that Japan must partly be de-industrialised. Dismantling of Japanese industry was foreseen to have been achieved when Japanese standards of living were reduced to those between 1930 and 1934[12]:531 [26] (see Great Depression). In the end the adopted program of de-industrialisation in Japan was implemented to a lesser degree than the similar U.S. "industrial disarmament" program in Germany.[12]:531

Current

A notable event began in the 1990s as the economy of Japan suddenly stagnated after three decades of tremendous economic growth. This could be construed as directly linked to deindustrialisation, as this phenomenon began to be recognised in developed countries of the world around this same time. However, Japan had larger economic problems, the effects of which can still be seen in the country's low economic growth today. According to data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2008), deindustrialisation is occurring in Japan. However, although industrial employment as a percentage of total employment has dropped over the last couple of decades in Japan, total employment has not. Unemployment was fairly low at 3.5% in 2007,[10] and the economy is relatively stable. Literature (Matsumoto 1996) has stated that the service sector has been expanding and providing jobs for those that have been displaced from industry. Strong union membership has also played a role in keeping employment rates stable. Although outsourcing and industrial decline may contribute to job loss in industry, the shift in modern economies from industry to service may help reduce negative effects.

Netherlands

Much like many other OECD countries, the Netherlands is not experiencing deindustrialisation in the usual way one might think of it. While the OECD's Annual Labour Force Statistics Survey may show that industrial employment opportunities in the Netherlands have significantly decreased in the past 50 years, the OECD's Production and Sales MEI for Industry and Service Statistics shows that the overall production in the industrial sector has actually improved. The Netherlands, like many other countries, has advanced to produce more with less.

Also, perhaps in response to the decline in industrial sector employment, the service industry of the Netherlands has grown and expanded its employment opportunities. The timely response of alternatives for employment may have had something to do with the progressive policies the Netherlands has in place to complement the changes in industry. An example might include tax breaks for families where the father works full-time and the mother works part-time, also referred to as the "one-and-a-half breadwinner" policy.

New Zealand

New Zealand is in a phase of deindustrialisation starting in the late 1990s. The evidence for this phenomenon is apparent in the decrease of economic output, a shift from employment in the manufacturing sector to the service sector (which may be due to an increase in tourism), the dissipation of unions caused by immigration and individual work contracts, along with the influence on culture by highbrow mass media (like the internet) and technology. It is possible to interpret these trends in a different way due to the complex nature of the data and the difficulty in quantifying and calculating reliable results. These trends are important to study, because they might occur in waves that could help predict economic and cultural outcomes in the future.

With the reduction and removal of tariffs through the 1980s and 1990s plus the importation of second hand Japanese cars, the major assembly plants began to close. New Zealand Motor Corporation which had closed its aging Newmarket plant in 1976 and Petone plant in 1982 closed their Panmure plant in 1988. General Motors closed its Petone plant in 1984 and its Trentham plant in 1990. 1987 saw a run of closures: Motor Industries International, Otahuhu, Ford Seaview, Motor Holdings Waitara. Suzuki in Wanganui closed 1988 and VANZ (Vehicle Assemblers of New Zealand a joint Ford and Mazda operation) at Sylvia Park in 1997. Toyota Christchurch in 1996 and VANZ Wiri the next year. Finally in 1998 along with Mitsubishi Porirua, bought from Todd in 1987, Nissan shutdown at Wiri, Honda closed in Nelson and Toyota in Thames.[27]

Redundancies occurred in manufacturing industry; approximately 76,000 manufacturing jobs were lost between 1987 and 1992.[28]

Poland

In Poland, as in many other former communist countries, deindustrialisation occurred rapidly in the years after the fall of communism in 1989, with many unprofitable industries going bankrupt with the switch to market economy, and other state-owned industries being destroyed by a variety of means, including arbitrarily changed credit and tax policies. The deindustrialisation in Poland was based on a neoliberalism-inspired doctrine (systemic transformation according to the requirements of Western financial institutions) and on the conviction that industry-based economy was a thing of the past. However, the extent of deindustrialisation was greater in Poland than in other European, including post-communist, countries: more than ⅓ of total large and midsize industrial assets were eliminated. The perceived economic reasons for deindustrialisation were reinforced by political and ideological motivations, such as removal of the remaining socialist influences concentrated in large enterprises (opposed to rapid privatization and shock therapy, as prescribed by the Balcerowicz Plan) and by land speculation (plants were sold at prices even lower than the value of the land on which they were located). Among such "privatized" institutions there were many cases of hostile takeovers (involved in 23% of all assets transferred), when industrial entities were sold and then changed to the service sector or liquidated to facilitate a takeover of the old company's market by the buying (typically foreign) firm.[29][30][31]

According to comprehensive research data compiled by economist Andrzej Karpiński and others, 25-30% of the reductions were economically justified, while the rest resulted from various processes that were controversial, often erroneous or pathological, including actions aimed at quick self-enrichment on the part of people with decision-making capacities. Unlike in the case of the Western deindustrialisation of the preceding years, in Poland modern competitive industries with established markets were also eliminated, including the electronic, telecommunications, computer, industrial machinery, armament and chemical industries. The abandoned domestic and foreign markets, often in Eastern Europe and the Third World countries, had subsequently been taken over by non-Polish interests. Nearly half (47%) of the lost enterprises represented consumer product light industry, rather than heavy industry. Capitalist Poland's early economic policies resulted in economic and social crises including high unemployment, and in what some see as irredeemable losses, impacting Poland's situation today. At the same time however, many constructive developments took place, including the widespread rise of entrepreneurship, and, especially after Poland joined the European Union, significant economic growth. The transformation process, as executed, generally replaced large enterprises with small, creating an environment inimical to innovation but conducive to human capital flight.[29][30][31]

The evaluation of Poland's economic advancement depends on the criteria used. For example, the country's industrial output had increased 2.4 times between 1989 and 2015, while the Polish GDP's percentage of the gross world product dropped from 2.4 in 1980 to 0.5-0.6 in 2015. In a number of measured categories of progress, Poland places behind its European Union formerly communist near neighbors (the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Lithuania), which had not undertaken deindustrialisation policies as radical as that of Poland.[30][31][32]

Soviet Union

Prior to its dissolution in 1991, the USSR had the second largest economy in the world after the United States.[33] The economy of the Soviet Union was the modern world's first centrally planned economy. It was based on a system of state ownership and managed through Gosplan (the State Planning Commission), Gosbank (the State Bank) and Gossnab (State Commission for Materials and Equipment Supply). Economic planning was through a series of five-year plans. The emphasis was put on rapid development of heavy industry, and the nation became one of the world's top manufacturers of a large number of basic and heavy industrial products, but it lagged behind in the output of light industrial production and consumer durables.

As the Soviet economy grew more complex, it required more and more complex disaggregation of control figures (plan targets) and factory inputs. As it required more communication between the enterprises and the planning ministries, and as the number of enterprises, trusts, and ministries multiplied, the Soviet economy started stagnating. The Soviet economy was increasingly sluggish when it came to responding to change, adapting cost−saving technologies, and providing incentives at all levels to improve growth, productivity and efficiency.

Most information in the Soviet economy flowed from the top down, and economic planning was often done based on faulty or outdated information, particularly in sectors with large numbers of consumers. As a result, some goods tended to be underproduced, leading to shortages, while other goods were overproduced and accumulated in storage. Some factories developed a system of barter and either exchanged or shared raw materials and parts, while consumers developed a black market for goods that were particularly sought after but constantly underproduced.

Conceding the weaknesses of their past approaches in solving new problems, the leaders of the late 1980s, headed by Mikhail Gorbachev, were seeking to mold a program of economic reform to galvanise the economy. However, by 1990 the Soviet government had lost control over economic conditions. Government spending increased sharply as an increasing number of unprofitable enterprises required state support and consumer price subsidies to continue.

The industrial production system in the Soviet Union suffered a political and economic collapse in 1991, after which a transition from centrally planned to market-driven economies occurred. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the economic integration of the Soviet republics was dissolved, and overall industrial activity declined substantially.[34] A lasting legacy remains in the physical infrastructure created during decades of combined industrial production practices.

Sweden

Sweden's industrial sector presents diverging information in production output and industrial employment levels. Using OECD (2008) data, specific statements can be made about these elements. With this data, it can be seen that production output within the industrial sector has been constantly rising. Contrastingly, employment within industry has been steadily declining since the 1970s, as service sector employment rates increase. Though the decline in industrial employment points to a deindustrialising economy, the increasing levels of production output state otherwise.

Sweden's industrial sector remains intact as it relies on its resource base of timber, hydropower, and iron ore as a large economic contributor.[35] Because of its increased production rates in industry, it can be ascertained that deindustrialisation has not occurred in Sweden. The decrease in industrial employment has been countered by an increase in efficiency and automation, increasing output levels in the industrial sector.

Switzerland

Deindustrialisation is a phenomenon that has been occurring in Switzerland since the mid-1970s. Civilian employment in industry has been in decline since 1975, according to OECD (2008) data, due to a major recession in the market. Literature (Afonso 2005) has stated that this is due to large numbers of migrant workers being forced to leave the country thanks to nonrenewable working permits; the industry, heavily based in foreign labour, suffered greatly and those losses are still observed in the present. Production of total industry has been increasing consistently at a slow rate since a slight decline in 1974.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom has experienced considerable deindustrialisation, especially in both heavy industry (such as mining and steel) and light manufacturing. New jobs have appeared with either low wages, or with high skill requirements that the laid-off workers lack. Meanwhile, the political reverberations have been growing.[36][37] Jim Tomlinson agrees that deindustrialization is a major phernomenon but denies that it represents a decline or failure.[38]

The UK's share of manufacturing output had risen from 9.5% in 1830, during the Industrial Revolution, to 22.9% in the 1870s. It fell to 13.6% by 1913, 10.7% by 1938, and 4.9% by 1973.[39] Overseas competition, trade unionism, the welfare state, loss of the British Empire, and lack of innovation have all been put forward as explanations for the industrial decline.[40] It reached crisis point in the 1970s, with a worldwide energy crisis, high inflation, and a dramatic influx of low-cost manufactured goods from Asia. Coal mining quickly collapsed and practically disappeared by the 21st century.[41] Railways were decrepit, more textile mills closed than opened, steel employment fell sharply, and the car-making industry suffered. Popular responses varied a great deal;[42] Tim Strangleman et al. found a range of responses from the affected workers: for example, some invoked a glorious industrial past to cope with their new-found personal economic insecurity, while others looked to the European Union for help.[43] It has been argued that these reverberations contributed towards the popular vote in favour of Brexit in 2016.[44]

Economists developed two alternative interpretations to explain de-industrialization in Britain. The first was developed by Oxford economists Robert Bacon and Walter Eltis. They argue that the public sector expansion deprived the private sector of sufficient labour and capital. In a word, the government “crowded out” the private sector. A variation of this theory emphasizes the increases in taxation cut the funds needed for wages and profits. Union demands for higher wage rates resulted in lower profitability in the private sector, and a fall in investment. However, many economists counter that public expenditures have lowered unemployment levels, not increased them.[45][46][47]

The second explanation is the New Cambridge model associated with Wynne Godley and Francis Cripps.[48] It stresses the long-term Decline and competitiveness of British industry. During the 1970s especially, the manufacturing sector steadily lost its share of both home and international markets. The historic substantial surplus of exports over Imports slipped into an even balance. That balance is maintained by North Sea oil primarily, and to a lesser extent from some efficiency improvement in agriculture and service sectors. The New Cambridge model posits several different causes for the decline in competitiveness. Down to the 1970's, the model stresses bad delivery times, poor design of products, and general low-quality. The implication is that although research levels are high in Britain, industry has been laggard in implementing innovation. The model after 1979 points to the appreciation of sterling against other currencies, so that British products are more expensive. In terms of policy, the New Cambridge model recommends general import controls, or else unemployment will continue to mount.[49] The model indicates that deindustrialization is a serious problem which threatens the nation's ability to maintain balance of payments equilibrium in the long run. The situation after North Sea oil runs out appears troublesome. De-industrialization imposes that serious social consequences. Workers skilled in the manufacturing sector are no longer needed, and are shuffled off to lower paying, less technologically valuable jobs. Computization and globalization are are compounding that problem.[50]

United States

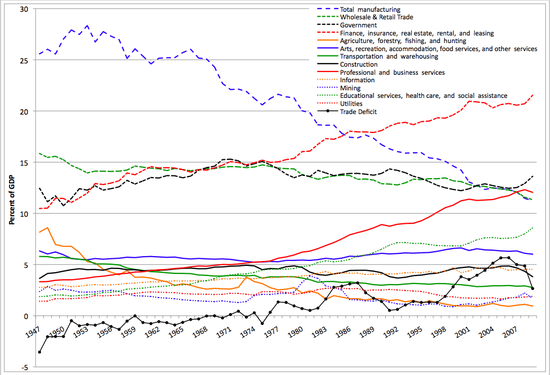

In the United States, deindustrialisation is mostly a regional phenomenon, centred on the Rust Belt of the original industrial centres from New England to the Great Lakes. While many Americans put the timing of industrial crisis as 1979 to 1984, in fact the most massive loss of US manufacturing jobs occurred in the 21st century: one third of US manufacturing jobs disappeared between 2001 and 2009, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.[53]

The mainstream of the economics professions argues nonetheless that loss of manufacturing jobs is not a problem for the following reasons: real industrial production rose in the United States in most years from 1983 to 2007. The argument is then that machines are replacing workers in the sense that more output is being produced by the same number of workers. In addition, the overall US labour force has increased dramatically, resulting in a massive reduction in the percent of the labour force engaged in industry (from over 35% in the late 1960s to under 20% today). Industry (and specifically manufacturing) is thus less prominent in American life and the American economy now than in over a hundred years.

However, the interpretation that manufacturing employment declined as a result of replacing people with machines has not addressed the issue that US non-financial firms seriously dropped their investment in fixed capital as a percent of operating profits between 2001 and 2009 (see NIPA accounts at www.bea.gov). It appears that far from buying robots, US manufacturing firms may be buying fewer machines as well as hiring fewer workers. In general, the literature that argues loss of US manufacturing jobs is inevitable in an advanced capitalist nation does also not grapple with the prominent role of manufacturing in advanced economies such as Germany and Japan, which also tend to have unit labor costs at least as high (if not higher) than those of the United States, per the Conference Board.

In fact, industry does continue in the United States, for example, there are export-competitive producers of precision technology in New England. Thus, the perception that all industry has left the United States is due to shifting patterns in the geography and political geography of production, away from metropolitan centers (such as New York, Boston, Chicago, Oakland, toward more "rural" areas (such as Georgia or New Hampshire or Utah). Since most Americans live in large cities, most Americans see empty factories, even if plants are operating well in other locations. Some argue also that the shift has been (from the heavily unionised Northeast and Midwest towards the Southeast and the high supply of workers (largely immigrant, first-generation, and second-generation) willing to accept low wages in the Southwest), along with increasing labour productivity, which has led to higher levels of output without increases in the total number of workers. Many argue that the textile industry, was the dominant factor in the industrialisation of New England, and in the 20th century increasingly textile factories were moved to the South. In recent decades the South has also lost its textile firms.[54]

Yet it would be inaccurate to argue that the only sectors to leave New England after 1980 were labor-intensive sector such as shoes and textiles, and there are many non-union firms in New England today. Rather, even high productivity sectors in which the US might be expected to have a comparative advantage such as machine tool production departed the United States between 1980 and 1985. This is arguably because the US Federal Reserve advocated for a strong dollar policy, at precisely the moment when German and Japanese manufacturers had falling costs due to rising productivity (post WW II catch-up was complete). Under the circumstances of falling Japanese prices, for example, only a decline in the value of the US dollar could have kept US machine tools competitive. The fact that the US Federal Reserve followed precisely the opposite policy and caused the dollar to appreciate 1979 to 1984 was a death blow to New England's machine tools. In 1986, the Fed recognized its mistake and negotiated the devaluation of the dollar against the Yen and the German Mark with the Plaza Accords, but by then it was too late for many firms, which either closed, laid off hundreds, or were sold to conglomerates during the down periods.[55]

Certain sectors of manufacturing remain vibrant. The production of electronic equipment has risen by over 50%, while that of clothing has fallen by over 60%. Following a moderate downturn, industrial production grew slowly but steadily between 2003 and 2007. The sector, however, averaged less than 1% growth annually from 2000 to 2007; from early 2008, moreover, industrial production again declined, and by June 2009, had fallen by over 15% (the sharpest decline since the great depression). Output thereafter began to recover.[56]

The population of the United States has nearly doubled since the 1950s, adding approximately 150 million people. Yet, during this period (1950–2007), the proportion of the population living in the great manufacturing cities of the Northeast has declined significantly. During the 1950s, the nation's twenty largest cities held nearly a fifth of the US population. In 2006, this proportion has dropped to about one tenth of the population.[57]

Many small and mid-sized manufacturing cities in the Rust Belt experience similar fates. For instance, the city of Cumberland, Maryland, declined from a population of 39,483 in the 1940s to a population of 20,915 in 2005. The city of Detroit, Michigan, saw its population drop from a peak of 1,849,568 in 1950 to 713,777 in 2010, the largest drop in population of any major city in the U.S. (1,135,971) and the second largest drop in terms of percent of people lost (second only to St. Louis, Missouri's 62.7% drop).

One of the first industries to decline was the textile industry in New England, as its factories shifted to the South. Since the 1970s, textiles have also declined in the Southeast. New England responded by developing a high-tech economy, especially in education and medicine, using its very strong educational base.[58]

As Americans migrated away from the manufacturing centres, they formed sprawling suburbs, and many former small cities have grown tremendously in the last 50 years. In 2005 alone, Phoenix, Arizona has grown by 43,000 people, an increase in population greater than any other city in the United States. Contrast that with the fact that in 1950, Phoenix was only the 99th largest city in the nation with a population of 107,000. In 2005, the population has grown to 1.5 million, ranking as the sixth largest city proper in the US.[57]

References

- Hassall, David (12 April 2012). "Tomcar - New local vehicle manufacturer". GoAuto. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- "Toyota workers out of jobs as car manufacturer closes Altona plant". ABC News. Australia. 6 December 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- "Vehicle Exports". GM Holden. Archived from the original on 2009-09-15. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- "Holden To Stay After Government Promises $270 Million Assistance". Australian Manufacturing. 23 March 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- "South Australia stunned as GM announces Holden's closure in Adelaide in 2017". GM Holden. 12 December 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- "Exports-2008". Toyota Australia. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- "Exports-2011". Toyota Australia. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- Dunckley, Mathew (10 February 2014). "Toyota confirms exit from Australian manufacturing in 2017". Port Macquarie News. Portnews.com.au. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- Peter Anderson (1 January 2010). "ACCI Welcomes textiles and car tariff cuts (ACCI media release 003/10)" (PDF). Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- CIA World Factbook Archived 2007-08-28 at the Wayback Machine 2008

- Steven High, Industrial sunset: the making of North America's rust belt, 1969-1984 (University of Toronto Press, 2015).

- Frederick H. Gareau, "Morgenthau's Plan for Industrial Disarmament in Germany". The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 2 (June 1961)

- Michael R. Beschloss, The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941–1945, pg. 233

- James Stewart Martin. All Honorable Men (1950) pg. 191.

- John Gimbel, "On the Implementation of the Potsdam Agreement: An Essay on U.S. Postwar German Policy". Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 87, No. 2. (Jun., 1972), pp. 242-269.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-04-14. Retrieved 2010-09-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Ray Salvatore Jennings, "The Road Ahead: Lessons in Nation Building from Japan, Germany, and Afghanistan for Postwar Iraq". May 2003, Peaceworks No. 49, pp. 14,15 Archived 14 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Pas de Pagaille!" Time, July 28, 1947.

- Vladimir Petrov, Money and conquest; allied occupation currencies in World War II. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press (1967) p. 236 (Petrov footnotes Hammond, American Civil-Military Decisions, p. 443)

- Vladimir Petrov, Money and conquest; allied occupation currencies in World War II. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Press (1967) p. 263

- Angus Maddison (2006), "The World Economy", OECD Publishing, ISBN 92-64-02261-9, p. 263

- Gupta, Bishnupriya. "COTTON TEXTILES AND THE GREAT DIVERGENCE: LANCASHIRE, INDIA AND SHIFTING COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE, 1600-1850" (PDF). International Institute of Social History. Department of Economics, University of Warwick. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- Griffiths, Trevor (1992). "Inventive Activity in the British Textile Industry 1700-1800". Journal of Economic History. 52 (4): 881–906. doi:10.1017/S0022050700011943. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Bottomley, Sean (2014). The British Patent System and the Industrial Revolution 1700-1852: From Privilege to Property. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–9. ISBN 9781107058293.

- Landes, David (2003). The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the present (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 214–215. ISBN 9780521534024.

- (A footnote in Gareau states: "For a text of this decision, see Activities of the Far Eastern Commission. Report of the Secretary General, February, 1946 to July 10, 1947, Appendix 30, p. 85.")

- Mark Webster, page 193 Assembly, New Zealand Car Production 1921–1998 Reed 2002 ISBN 0 7900 0846 7

- Judith Bell, I See Red, Awa Press, Wellington: 2006, pp.22–56.

- Paweł Soroka (2015-08-18). "Polska po 1989 r. doświadczyła katastrofy przemysłowej. Czy możemy odbudować nasz potencjał? [After 1989 Poland experienced an industrial catastrophe. Can we rebuild our potential?]". forsal.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-31.

- Paweł Dybicz (conversation with Andrzej Karpiński) (2016-05-23). "Stracone szanse? [Lost chances?]". Przegląd. Retrieved 2016-06-01.

- "Gdyby nie masowa likwidacja przemysłu po 1989 roku, dziś zarabialibyśmy o ⅓ więcej [If not for the massive liquidation of industry after 1989, we would be earning ⅓ more today]". forsal.pl. 2016-05-24. Retrieved 2016-05-31.

- Eugeniusz Guz, "Polska w ogonie Europy [Poland in the tail of Europe]". Przegląd magazine #22(856), 30 May 2016

- "1990 CIA World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- Oldfield, J.D. (2000) "Structural economic change and the natural environment in the Russian Federation". Post-Communist Economies, 12(1): 77-90)

- CIA World Factbook 2008

- Tim Strangleman, James Rhodes, and Sherry Linkon, "Introduction to crumbling cultures: Deindustrialization, class, and memory." International Labor and Working-Class History 84 (2013): 7-22. online

- Steven High, "'The Wounds of Class': A Historiographical Reflection on the Study of Deindustrialization, 1973–2013." History Compass 11.11 (2013): 994-1007

- Jim Tomlinson, "De-industrialization not decline: a new meta-narrative for post-war British history." Twentieth Century British History 27.1 (2016): 76-99.

- Azar Gat (2008). War in Human Civilization. Oxford University Press. p. 519. ISBN 978-0-19-923663-3.

- Keith Laybourn (1999). Modern Britain Since 1906: A Reader. I.B.Tauris. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-86064-237-1.

- Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (2016). "Historical coal data: coal production, availability and consumption 1853 to 2015".

- For a detailed field study by an anthropologist, see Thorleifsson, Cathrine (2016). "From coal to Ukip: the struggle over identity in post-industrial Doncaster". History and Anthropology. Taylor and Francis. 27 (5): 555–568. doi:10.1080/02757206.2016.1219354.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Strangleman, Tim; Rhodes, James; Linkon, Sherry (Fall 2013). "From coal to Ukip: the struggle over identity in post-industrial Doncaster". International Labor and Working-Class History. Cambridge Journals. 84 (1): 7–22. doi:10.1017/S0147547913000227.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Pdf.

- O'Reilly, Jacqueline; et al. (October 2016). "Brexit: understanding the socio-economic origins and consequences (discussion forum)" (PDF). Socio-Economic Review. Oxford Journals. 14 (4): 807–854. doi:10.1093/ser/mww043.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Christopher Pick, ed., What's What in the 1980s (1982), pp 86-87.

- Robert Bacon and Walter Eltis, Britain's Economic Problem: Too Few Producers (2nd ed. 1978) excerpt.

- Robert Bacon and Walter Eltis, Britain’s economic problem revisited (Springer, 1996, second edition).

- Francis Cripps, and Wynne Godley, "A formal analysis of the Cambridge economic policy group model." Economica (1976): 335-348 online.

- Francis Cripps, and Wynne Godley, "Control of imports as a means to full employment and the expansion of world trade: the UK's case." Cambridge Journal of Economics 2.3 (1978): 327-334.

- Pick, What's What in the 1980s (1982), pp 86-878.

- National Welding and Manufacturing , U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, accessed 2009-09-07 Archived March 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Who Makes It?". Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- "US Bureau of Labor Statistics".

- David Koistinen, "Business and Regional Economic Decline: The Political Economy of Deindustrialization in Twentieth-Century New England" Business and economic history online (2014) #12

- Duggan, M.C. 2017 Duggan, MC 2017 "Deindustrialization in the Granite State" in Dollars and Sense, Nov/Dec issue.

- Federal Reserve

- Stephen Ohlemacher, "America's big cities are getting smaller", Associated Press

- David Koistinen, Confronting Decline: The Political Economy of Deindustrialization in Twentieth-Century New England (University Press of Florida; 2013)

Further reading

- Afonso, A. (2005) "When the Export of Social Problems is no Longer Possible: Immigration Policies and Unemployment in Switzerland," Social Policy and Administration, Vol. 39, No. 6, Pp. 653–668

- Baumol, W. J. (1967) 'Macroeconomics of Unbalanced Growth: The Anatomy of Urban Crisis,' The American Economic Review, Vol. 57, No. 3

- Boulhol, H. (2004) 'What is the impact of international trade on deindustrialisation in OECD countries?' Flash No.2004-206 Paris, CDC IXIS Capital Markets

- Brady, David, Jason Beckfield, and Wei Zhao. 2007. "The Consequences of Economic Globalization for Affluent Democracies." Annual Review of Sociology 33: 313-34.

- Bluestone, B. and Harrison, B. The Deindustrialization of America: Plant Closings, Community Abandonment and the Dismantling of Basic Industry. New York: Basic Books, 1982.

- Cairncross, A. (1982) 'What is deindustrialisation?' Pp. 5–17 in: Blackaby, F (Ed.) Deindustrialisation. London: Pergamon

- Cowie, J., Heathcott, J. and Bluestone, B. Beyond the Ruins: The Meanings of Deindustrialization Cornell University Press, 2003.

- Central Intelligence Agency. 2008. The CIA World Factbook

- Feinstein, Charles. 1999. "Structural Change in the Developed Countries During the Twentieth Century." Oxford Review of Economic Policy 15: 35-55.

- Fuchs, V. R. (1968) The Service Economy. New York, National Bureau of Economic Research

- Lever, W. F. (1991) 'Deindustrialisation and the Reality of the Post-industrial City'. Urban Studies, Vol. 28, No. 6, pp. 983-999

- Goldsmith, M. and Larsen, H. (2004) "Local Political Leadership: Nordic Style." International Journal of Urban and Regional Research Vol. 28.1, Pp. 121–133.

- Koistinen, David. Confronting Decline: The Political Economy of Deindustrialization in Twentieth-Century New England. (University Press of Florida, 2013)

- Koistinen, David. "Business and Regional Economic Decline: The Political Economy of Deindustrialization in Twentieth-Century New England" Business and economic history online (2014) #12

- Krugman, Paul. "Domestic Distortions and the Deindustrialization Hypothesis." NBER Working Paper 5473, NBER & Stanford University, March 1996.

- Kucera, D. and Milberg, W. (2003) "Deindustrialization and Changes in Manufacturing Trade: Factor Content Calculations for 1978-1995." Review of World Economics 2003, Vol. 139(4).

- Lee, Cheol-Sung. 2005. "International Migration, Deindustrialization and Union Decline in 16 Affluent OECD Countries, 1962-1997." Social Forces 84: 71-88.

- Logan, John R. and Swanstrom, Todd. Beyond City Limits: Urban Policy and Economic Restructuring in Comparative Perspective, Temple University Press, 1990.

- Matsumoto, Gentaro. 1996. "Deindustrialization in the UK: A Comparative Analysis with Japan." International Review of Applied Economics 10:273-87.

- Matthews, R. C. O., Feinstein, C. H. and Odling-Smee, J. C. (1982) British Economic Growth, Oxford University Press

- OECD Stat Extracts (2008)

- Pitelis, C. and Antonakis, N. (2003) 'Manufacturing and competitiveness: the case of Greece'. Journal of Economic Studies, Vol. 30, No. 5, Pp. 535–547

- Reisman, G. (2002) "Profit Inflation by the US Government"

- Rodger Doyle, "Deindustrialization: Why manufacturing continues to decline", Scientific American - May, 2002

- Rowthorn, R. (1992) 'Productivity and American Leadership – A Review...' Review of Income and Wealth, Vol. 38, No. 4

- Rowthorn, R. E. and Wells, J. R. (1987) De-industrialisation and Foreign Trade Cambridge University Press

- Rowthorn, R. E. and Ramaswamy, R. (1997) Deindustrialization–Its Causes and Implications, IMF Working Paper WP/97/42.

- Rowthorn, Robert and Ramana Ramaswamy (1999) 'Growth, Trade, and Deindustrialization' IMF Staff Papers, 46:18-41.

- Sachs, J. D. and Shatz, H. J. (1995) 'Trade and Jobs in US Manufacturing'. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity No. 1

- Vicino, Thomas, J. Transforming Race and Class in Suburbia: Decline in Metropolitan Baltimore. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Historiography

- High, Stephen. "The Wounds of Class": A Historiographical Reflection on the Study of Deindustrialization, 1973–2013," History Compass (2013) 11#11 pp 994–1007; on US and UK; DOI: 10.1111/hic3.12099