Colma, California

Colma is a small incorporated town in San Mateo County, California, on the San Francisco Peninsula in the San Francisco Bay Area. The population was 1,792 at the 2010 census. The town was founded as a necropolis in 1924.[6]

Colma, California | |

|---|---|

Town in California | |

| Town of Colma | |

A cemetery in Colma | |

Seal | |

| Motto(s): "It's great to be alive in Colma" | |

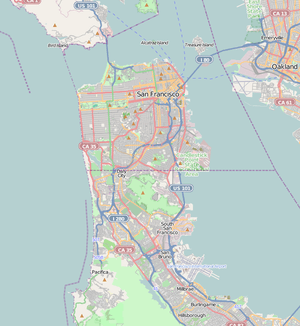

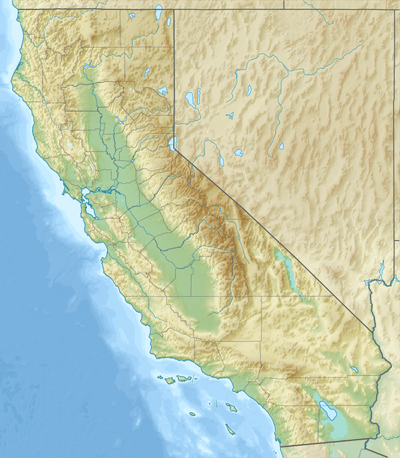

Location of Colma in San Mateo County, California | |

Colma, California Location of Colma  Colma, California Colma, California (San Francisco Bay Area)  Colma, California Colma, California (California)  Colma, California Colma, California (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 37°40′44″N 122°27′20″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | San Mateo |

| Incorporated as "Lawndale" | August 5, 1924[1] |

| Name changed to "Colma" | November 17, 1941 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor[2] | Joanne F. del Rosario |

| • City Manager[3] | Brian Dossey |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.89 sq mi (4.90 km2) |

| • Land | 1.89 sq mi (4.90 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) 0% |

| Elevation | 121 ft (37 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 1,792 |

| • Estimate (2019)[5] | 1,489 |

| • Density | 787.00/sq mi (303.84/km2) |

| United States Census Bureau | |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Code | 94014 |

| Area code(s) | 650 |

| FIPS code | 06-14736 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1658303 |

| Website | www.colma.ca.gov |

With most of Colma's land dedicated to cemeteries, the population of the dead—about 1.5 million, as of 2006—outnumbers that of the living by a ratio of nearly a thousand to one. This has led to Colma's being called "the City of the Silent" and has given rise to a humorous motto, now recorded on the city's website: "It's great to be alive in Colma".[6]

Etymology

The origin of the name Colma is widely disputed. Before 1872, Colma was designated as "Station" or "School House Station", the name of its post office in 1869. Currently, there seem to be seven possible sources of the town's being called Colma:[7]

- William T. Coleman, allegedly known as the "Lion of the Vigilantes" and a significant landowner in the area

- Thomas Coleman, a registered voter in the district during the 1870s

- A transfer name from Europe: Alsace has a Colmar

- A re-spelling of an ancient Uralic word meaning death

- A literary origin from James Macpherson's Songs of Selma, in one of the Ossianic fragments

- Native American languages:

- "Kolma" means "moon" in one dialect of the Costanoan, or the Ohlone people, who lived in the area; however, this name does not appear on any design ("diseño") of Indian rancherias at the time

- A local Native American word meaning "springs", of which many can be found around the city.[8]

- A corruption of Colima, a Mexican place name meaning volcano, but also ancestors.[9]

History

The community of Colma was formed in the 19th century as a collection of homes and small businesses along El Camino Real and the adjacent San Francisco and San Jose Railroad line. Several churches, including Holy Angels Catholic Church, were founded in these early years. The community founded its own fire district, which serves the unincorporated area of Colma north of the town limits, as well as the area that became a town in 1924.

Hienrich (Henry) von Kempf moved his wholesale nursery here in the early part of the 20th century, from the land where the Palace of Fine Arts currently sits (in what was known as "Cow Hollow") in San Francisco. The business was growing, and thus required more space for Hienrich's plants and trees. Hienrich then began petitioning to turn the Colma community into an agricultural township. He succeeded and became the town of Colma's first treasurer.

In the early 20th century, Colma was the site of many major boxing events. Middleweight world champion Stanley Ketchel held six bouts at the Mission Street Arena in Colma, including two world middleweight title bouts against Billy Papke and a world heavyweight title bout against Jack Johnson.[10]

San Francisco cemetery relocations

Colma became the site for numerous cemeteries after San Francisco outlawed new interments within city limits in 1900, then evicted all existing cemeteries in 1912. Approximately 150,000 bodies were moved between 1920 and 1941 at a cost of $10 per grave and marker. Those for whom no one paid the fee were reburied in mass graves, and the markers were recycled in various San Francisco public works.[11] The completion of the relocation was delayed until after World War II; these events are the subject of A Second Final Rest: The History of San Francisco's Lost Cemeteries (2005), a documentary by Trina Lopez.[12] The main rail line between San Francisco and San Jose running through Colma had been bypassed in 1907 for a route closer to the San Francisco Bay shoreline, and the former main line was repurposed as a branch line to move coffins to Colma. Decades later, the right-of-way for the rail line through Colma was purchased by BART for use in the San Francisco International Airport extension project.[11]

The Town of Lawndale was incorporated in 1924,[11] primarily at the behest of the cemetery owners with the cooperation of the handful of residents who lived closest to the cemeteries. The residential and business areas immediately to the north continued to be known as Colma. Because another California city named Lawndale already existed, in Los Angeles County, the post office retained the Colma designation, and the town changed its name back to Colma in 1941.[11]

Originally, Colma's residents were primarily employed in occupations related to the many cemeteries in the town. Since the 1980s, however, Colma has become more diversified, and a variety of retail businesses and automobile dealerships has brought more sales tax revenue to the town government.[6][13] In 1986, 280 Metro Center opened for business in Colma; it is now recognized as the world's first power center.[14][15]

Notable interments

Many, if not most, of the well-known people who died in San Francisco since the first cemeteries opened there have been buried or reburied in Colma, with an additional large number of such burials in Oakland's Mountain View Cemetery. Some notable people interred in Colma include:

- Cypress Lawn Memorial Park

- William Henry Crocker, business magnate

- Charles De Young, San Francisco Chronicle founder

- Phineas Gage, famous 19th-century medical curiosity

- Edward Gilbert, California politician and co-founder of the Alta California

- William Randolph Hearst, newspaper tycoon

- Ed Lee, first Asian American Mayor of San Francisco

- Willie McCovey, Major League Baseball Hall of Famer

- John McLaren, horticulturist

- Turk Murphy, jazz musician and bandleader

- Hills of Eternity and Home of Peace (side-by-side Jewish cemeteries)

- Wyatt Earp is buried next to his wife, Josephine Marcus Earp[6][16]

- Julie Rosewald, America's first female cantor[17]

- Levi Strauss, denim trouser pioneer

- Alice B. Toklas is not buried in Colma, though there is a large Toklas tombstone for her and markers there for some of her relatives[16]

- Holy Cross Cemetery

- Joseph Alioto, San Francisco mayor

- Pat Brown, 32nd governor of California

- Beniamino Bufano, sculptor, noted for peace monuments and other statues

- Patrick and Terence Casey, the San Francisco brothers team of pulp writers

- Frank "the Crow" Crosetti, New York Yankees shortstop

- Joe DiMaggio, Yankees center fielder[6]

- Abigail Folger, coffee heiress and Manson murder victim

- A.P. Giannini, Bank of America founder

- Vince Guaraldi, jazz musician

- James D. Phelan, senator

- Woodlawn Cemetery

- Thomas Henry Blythe (born Thomas Williams, 1822–1883), emigrated to San Francisco from Wales and became a wealthy capitalist.

- Henry Miller, California cattle rancher

- Joshua Abraham "Emperor" Norton, a late-1800s San Francisco celebrity known as "Emperor of these United States and Protector of Mexico"

- José Sarria, LGBT political activist who styled himself "The Widow Norton" in reference to Norton[16]

- Eternal Home Cemetery (Jewish cemetery)

- Bill Graham, music promoter

- Greek Orthodox Memorial Park

- George Christopher, San Francisco mayor

- Nicholas Doukas, founder of Greek Orthodox Memorial Park

- Stacey Doukas, photographer

- Greenlawn Memorial Cemetery

- James Rolph, San Francisco mayor and 27th governor of California

Geography and geology

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 1.9 sq mi (4.9 km2), all land. The town's 17 cemeteries comprise approximately 73% of the town's land area.[6]

Colma is situated on the San Francisco Peninsula at the highest point of the Merced Valley, a gap between San Bruno Mountain and the northernmost foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountain Range.[18][19] The foothills and eastern flanks of the range are composed largely of poorly consolidated Pliocene-Quaternary freshwater and shallow marine sediments that include the Colma and Merced Formations, recent slope wash, ravine fill, colluvium, and alluvium. These surficial deposits unconformably overlay the much older Jurassic to Cretaceous-aged Franciscan Assemblage. An old landfill about 135 deep existed at the site developed by the 260,000 sq ft (24,000 m2) mixed-use Metro Center.[20]

Colma Creek flows through the city as it makes its way from San Bruno Mountain to San Francisco Bay.

Education

Colma has one private school, Holy Angels School, a Catholic school for preschool through 8th grade.[21]

Colma belongs to the Jefferson Elementary School District, which has two schools in Colma: Garden Village Elementary (grades K–5) and Benjamin Franklin Intermediate (grades 6–8). High school students typically attend Westmoor High School in the Jefferson Union High School District.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 188 | — | |

| 1930 | 369 | — | |

| 1940 | 354 | −4.1% | |

| 1950 | 297 | −16.1% | |

| 1960 | 500 | 68.4% | |

| 1970 | 537 | 7.4% | |

| 1980 | 395 | −26.4% | |

| 1990 | 1,103 | 179.2% | |

| 2000 | 1,191 | 8.0% | |

| 2010 | 1,792 | 50.5% | |

| Est. 2019 | 1,489 | [5] | −16.9% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[22] | |||

Informally, as of 2006 Colma had "1,500 aboveground residents ... and 1.5 million underground".[6]

2010

The 2010 United States Census[23] reported that Colma had a population of 1,792. The population density was 938.6 people per square mile (362.4/km2). The racial makeup of Colma was 620 (34.6%) White, 59 (3.3%) African American, 7 (0.4%) Native American, 619 (34.5%) Asian, 9 (0.5%) Pacific Islander, 366 (20.4%) from other races, and 112 (6.3%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 708 persons (39.5%).

The Census reported that 1,763 people (98.4% of the population) lived in households, 0 (0%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 29 (1.6%) were institutionalized.

There were 564 households, out of which 217 (38.5%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 271 (48.0%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 110 (19.5%) had a female householder with no husband present, 42 (7.4%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 44 (7.8%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 8 (1.4%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 91 households (16.1%) were made up of individuals, and 31 (5.5%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.13. There were 423 families (75.0% of all households); the average family size was 3.45.

The population was spread out, with 390 people (21.8%) under the age of 18, 178 people (9.9%) aged 18 to 24, 532 people (29.7%) aged 25 to 44, 488 people (27.2%) aged 45 to 64, and 204 people (11.4%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36.4 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.9 males.

There were 586 housing units at an average density of 306.9 per square mile (118.5/km2), of which 224 (39.7%) were owner-occupied, and 340 (60.3%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.7%; the rental vacancy rate was 2.3%. 738 people (41.2% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 1,025 people (57.2%) lived in rental housing units.

2000

In the census[24] of 2000, there were 1,191 people, 329 households, and 245 families residing in the town. The population density was 624.6 people per square mile (240.8/km2). There were 342 housing units at an average density of 179.4 per square mile (69.1/km2).

There were 329 households, out of which 36.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 57.1% were married couples living together, 11.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 25.5% were non-families. 17.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.47 and the average family size was 3.92.

In the town the population was spread out, with 24.7% under the age of 18, 8.9% from 18 to 24, 31.7% from 25 to 44, 19.1% from 45 to 64, and 15.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 87.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.9 males.

The median income for a household in the town was US$58,750, and the median income for a family was US$60,556. Males had a median income of US$32,059 versus US$29,934 for females. The per capita income for the town was US$20,241. About 3.4% of families and 5.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 4.8% of those under age 18 and 3.7% of those age 65 or over.

In popular culture

- Harold and Maude, (1971), a dark comedy about a death-obsessed young man and a vivacious older woman, filmed scenes at Holy Cross Cemetery and elsewhere on the Peninsula.[25]

- Tales of the City (novel and 1993 miniseries) has a minor character named Candi Moretti, a waitress whose name tag says she is from Colma.

- Colma (1998), the fourth studio album released by guitarist Buckethead, makes reference to the town of Colma.[26]

- A Second Final Rest: The History of San Francisco's Lost Cemeteries (2005), by Trina Lopez, documents the relocation of cemeteries from San Francisco to Colma.[12]

- Alive in Necropolis (2008), a novel by Doug Dorst.

- Colma: The Musical (2007) is an American independent film that was shot on location in Colma and Daly City. The film has won several special jury prizes at local and international film festivals.[27][28]

- Colma: A Journey of Souls (2014) is a documentary film about the history of Colma, produced by Kingston Media in association with the Colma Historical Society.[29]

References

- "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- . Colma.ca.gov. Retrieved on 2019-01-20.

- City Manager Home. Colma.ca.gov. Retrieved on 2013-07-21.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Pogash, Carol (3 December 2006). "Colma, Calif., Is a Town of 2.2 Square Miles, Most of It 6 Feet Deep". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- Gudde, Erwin G. California Place Names: The Origin and Etymology of Current Geographical Names (4th ed.). University of California Press. p. 86.

- "And Just How Are Things in Colma, Calif.? Awfully Quiet, Night and Day". New York Times. April 21, 1996. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- "Colima Origin", nationsencyclopedia.com, Thomson Gale, 4 July 2006,

Colima Pronunciation: koh-LEE-mah. Origin of state name: From the Náhuatl (Amerindian) word collimaitl. Colli means either ancestors or volcano, and maitl means domain of. Capital: Colima.

CS1 maint: date and year (link) - "Stanley Ketchel - Boxer". Boxrec.com. October 15, 1910. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- Branch, John (February 5, 2016). "The Town of Colma, Where San Francisco's Dead Live". The New York Times. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- Bressler, Janice (July 3, 2018). "New film highlights history of Richmond's lost cemeteries". Richmond ReView / Sunset Beacon. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- Boudreau, John (12 June 1994). "Couldn't you just die? Necropolis USA: One town's underground economy". The Washington Post. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Laird, Gordon (2009). The Price of a Bargain: The Quest for Cheap and the Death of Globalization. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. p. 68. ISBN 9781551993287. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- Pacione, Michael (2009). Urban Geography: A Global Perspective (3rd ed.). Milton Park: Routledge. p. 249. ISBN 9780415462013. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- Roisman, Jon (November 6, 2014). "Local Jewish history comes to life at cemetery walk". JWeekly.com.

- Roisman, Jon. "Local Jewish history comes to life at cemetery walk". J. The Jewish News of Northern California. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

Actors, many of them professional, portrayed a number of local Jewish luminaries, such as Levi Strauss, Alice B. Toklas and Joshua Abraham Norton, a late 1800s San Francisco celebrity better known as “Emperor Norton.” [...] notable Jews buried there, including Julie Rosewald (America’s first female cantor) and Josephine Earp (wife of famed lawman Wyatt Earp, who is buried at her side).

- Colma Cardroom Project, Environmental Impact Report, Environmental Science Associates, prepared for the city of Colma (1993); IV.B. "Geology and Soils" Archived 2015-07-25 at the Wayback Machine.

- About the Mountain: Topography and Climate Archived 2015-07-25 at the Wayback Machine, San Bruno Mountain Watch (nd).

- M.Papineau, B.George, J.Buxton et al., Environmental Impact Report for the Metro Center, Colma, California, Earth Metrics report 10062, prepared for the city of Colma and the California State Clearinghouse (1989)

- "About Us". Holy Angels School. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Colma town". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Harold and Maude Bay Area Filming Locations". Harold and Maude homepage. Archived from the original on 15 September 2019. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

Bay Area Location: Holy Cross Cemetery on Old Mision[sic] Road in Colma.

- "Colma - Buckethead — Listen and discover music at Last.fm". www.last.fm. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

The album was recorded for Buckethead's mother as she was ill with colon cancer and he wanted to make an album she would enjoy listening to whilst recovering. The title of the album makes reference to the small town of Colma near San Francisco, California, where "the dead population outnumber the living by thousands to one".

- Manohla Dargis (July 6, 2007). "Big Teenage Dreams, Small-Town Doldrums". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-05-28.

- "Colma: The Musical". GreenRockSolid. 5 July 2007. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- Livengood, Carolyn (October 30, 2014). "Veterans Day to be observed at Golden Gate National Cemetery". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved October 5, 2018.