Cyclone Anne

Severe Tropical Cyclone Anne was one of the most intense tropical cyclones within the South Pacific basin during the 1980s. The cyclone was first noted on January 5, 1988 as a weak tropical depression to the northeast of Tuvalu, in conjunction with the future Typhoon Roy in the Northern Hemisphere. Over the next few days, the system gradually developed while moving southwestward. Once it became a tropical cyclone, it was named Anne on January 8. The next day, Anne rapidly intensified, becoming the fourth major tropical cyclone to affect Vanuatu within four years. On January 11, Anne peaked in intensity while it was equivalent to a Category 5 on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale, and a Category 4 on the Australian tropical cyclone intensity scale. After turning southward on January 12, Anne struck New Caledonia, becoming the strongest tropical cyclone to affect the French Overseas Territory. The system subsequently weakened as it started to interact with Tropical Cyclone Agi. Anne weakened into a depression and was last noted on January 14 to the south-east of New Caledonia.

| Category 4 severe tropical cyclone (Aus scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 5 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

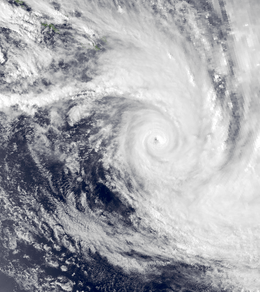

Cyclone Anne on January 11 near its peak intensity | |

| Formed | January 5, 1988 |

| Dissipated | January 14, 1988 |

| Highest winds | 10-minute sustained: 185 km/h (115 mph) 1-minute sustained: 260 km/h (160 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 925 hPa (mbar); 27.32 inHg |

| Fatalities | 2 |

| Damage | $500,000 (1987 USD) |

| Areas affected | Tuvalu, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, New Caledonia |

| Part of the 1987–88 South Pacific cyclone season | |

Several islands within the Solomon Islands reported extensive property and crop damage. Within Vanuatu, Anne brought heavy rains, flooding, and a storm surge. These effects damaged houses, crops, and property, especially on Ureparapara islands and the Torres Islands. Extensive damage was reported in New Caledonia after it was exposed to a prolonged period of storm force winds, with the eastern and southern coasts particularly affected. On January 12, the system produced the highest daily rainfall totals since 1951 in several areas. Two people were killed after they attempted to cross a flooded river, and about 80 others were injured by the cyclone. Due to the impact of this storm, the name Anne was retired.

Meteorological history

On January 5, 1988, the Fiji Meteorological Service (FMS) started to monitor a shallow tropical depression that developed within the monsoon trough about 540 km (335 mi) northeast of Tuvalu.[1][2][3] At around the same time, a twin depression developed within the Northern Hemisphere monsoon trough, which eventually became Typhoon Roy.[4] Over the next two days the Southern Hemisphere system developed further as it was steered towards the south-southwest along an area of high pressure, before it became equivalent to a tropical storm while passing through the Tuvaluan islands.[3][1][5] As a result, the United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) designated the system as Tropical Cyclone 07P and started to issue advisories on it.[3][6] After organized further, the FMS named the storm Anne after it became equivalent to a modern-day Category 2 on the Australian tropical cyclone intensity scale.[1][2][3] On January 9, the cyclone started to rapidly intensify while continuing to move towards the south-southwest. Later that day, the JTWC reported that the system had become equivalent to a Category 1 on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale (SSHWS), and the FMS upgraded Anne to a Category 3 severe tropical cyclone on the Australian Scale.[1][3] Early on January 10, the cyclone passed through Temotu Province and about 55 km (35 mi) to the northwest of Anuta Island.[1][3]

Later on January 10, Anne directly passed over Vanuatu's Torres Islands and came within 65 km (40 mi) of Ureparapara in the Banks Islands.[1] The cyclone continued to move to the south-southwest and affected the northern islands of Vanautu.[1] Early on January 11, the FMS reported that Anne had peaked, with estimated 10-minute sustained winds near its center of 185 km/h (115 mph), equivalent to a Category 4 severe tropical cyclone on the Australian scale.[1][3] At around the same time the JTWC reported that Anne had peak 1-minute peak sustained winds of 260 km/h (160 mph), which made it equivalent to a Category 5 hurricane on the SSHWS.[3][6] This made it one of the most intense tropical cyclones of the 1980s.[1] Over the next day, Cyclone Anne turned south and rapidly weakened as it encountered upper-level wind shear, approaching the French overseas territory of New Caledonia.[1] Late on January 12, Anne weakened into a modern-day Category 2 tropical cyclone, before it made landfall on New Caledonia about 110 km (70 mi) to the north-northwest of Noumea.[1] After the cyclone re-emerged into the Coral Sea, the JTWC downgraded Anne to tropical storm status.[3] Later on January 13, Cyclone Anne started to interact with Cyclone Agi, which had rapidly moved south-eastward towards the "relatively deeper" Anne.[1][3][7] Agi had developed two days prior near the Louisiade Archipelago, about 1,200 km (745 mi) northwest of Cyclone Anne.[3][7] Early on January 14, Anne weakened into a depression and subsequently dissipated southeast of New Caledonia as it was caught up in the upper westerly flow.[2][6][3]

Preparations and impact

During its early stages of development, Anne passed through the central islands of Tuvalu, causing minor damage to houses and crops such as bananas and coconuts.[1] The storm passed to the north of Funafuti where strong gale force winds of 70 km/h (45 mph) were recorded.[8] The system subsequently affected the Solomon Island province of Temotu between January 9 – 10 while it had sustained winds of 150 km/h (95 mph).[1] However, the cyclone's center did not pass directly over any island, and the smaller islands escaped the destructive hurricane-force winds.[1] Because Anne moved through the province at about 30 km/h (20 mph), any gale and storm force winds that affected the islands were not prolonged.[9] Anuta, Utupua, the Duff Islands and the Reef Islands all reported extensive damage to property and crops, with at least 25 houses and 5 classrooms damaged.[9][10]

The system affected the Northern Vanuatu Islands between January 10 – 11 and was the fourth major tropical cyclone to affect the island nation since 1985, after Severe Tropical Cyclones Eric, Nigel and Uma.[11] Ahead of Anne affecting Vanuatu, various alerts and warnings were issued including a hurricane warning.[10] During January 10, the cyclone directly passed over the Torres Islands and came within 65 km (40 mi) of the Banks Islands, although it missed Vanuatu's most populated districts around Port Vila and the rest of Espiritu Santo.[1][12] Within Vanuatu, over 1600 people were made homeless while wind gusts of up to 225 km/h (140 mph) were recorded.[11][13][14] Torrential rain, flooding and storm surge caused damage to houses, crops and property while triggering a landslide on the island of Epi.[11][13][14] The hardest hit area was Torba Province with severe damage recorded on the islands of Ureparapara and the Torres Islands, while extensive damage was recorded on the islands of Vanua Lava and Gaua.[10][11][15] Within the province, virtually the whole population lost their houses, as well as their cash crops.[15][16] There were reports of 4–5 m (13–16 ft) tidal waves, washing away houses on the west coast of Ureparapara, while significant wave heights of over 11 m (36 ft) were recorded.[1][17] Within the province of Sanma, severe damage was recorded on Espiritu Santo after Anne flooded huts, unroofed school buildings, uprooted coconut trees and destroyed the main wharf.[16][18] Overall the total damages from Anne in Vanuatu, were estimated at US$500 thousand.[19]

In conjunction with Tropical Cyclone Agi, Anne affected the whole of New Caledonia between January 11–15, becoming the most powerful tropical cyclone to affect the French overseas territory in 12 years.[20] Winds in Noumea reached up to 150 km/h (95 mph), although there was no serious damage there.[21] Prolonged storm force winds left extensive damage to the island, with the eastern and southern coasts particularly affected.[1][10] On January 12, the system produced the highest daily rainfall totals since 1951, with Noumea recording 262 mm (10.3 in).[22]

Larger rainfall totals included 713 mm (28.1 in) in Goro and 519 mm (20.4 in) in Thio.[23] Two people were killed after they attempted to cross a flooded river.[20] Floods also swept away crops, huts and topsoil belonging to indigenous Melanesians that lived in coastal villages.[24][25] Some areas reported crop damage between 90 and 100%.[10][26] Most of the roads within the territory were left unusable while all international flights to the territory were cancelled.[21] About half of the houses in Poindimié were damaged or destroyed.[21] The last wooden Royal Navy boat was scheduled to be sunk on January 12, but was moved to January 19 due to the cyclones.[27][28] Overall, there were about 80 injuries related to the cyclone in New Caledonia.[20]

Aftermath

The aftermath of the cyclone was marked by a distinct lack of a quantitative assessment within the Solomon Islands; with few boats or aircraft near the remote islands, relief measures were slow to get underway.[9] However, 11 men aboard the United States Navy vessel USS Barbour County received Humanitarian Service Medals from the United States Department of Defense after aiding storm victims on Tikopia and Anuta from January 16 to 19.[29][30][31]

With some residents forced to seek refuge in caves, the Government of Vanuatu asked the Australian, New Zealand and American governments for emergency food supplies and other assistance.[10][15][16] In accordance, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) dispatched two Hercules transport planes to help with recovery efforts.[32] The first carried a helicopter that transported Vanuatu military forces, medical teams and supplies to the affected northern islands, especially remote villages inaccessible to larger aircraft.[12][32][33] The other plane was used to transport more than 16,000 kilograms (35,000 lb) of fuel and relief supplies including food and shelter provisions.[32][34] The Royal New Zealand Air Force also provided a plane, which transported relief supplies from Espiritu Santo to the northern islands up to three times daily, with the bulk of supplies donated by Australia.[12] The European Commission provided Vanuatu with €100,000 in emergency aid to purchase local foods, including rice, preserved meat, and fish, and to distribute it to Anne's victims.[35] The total cost of relief and reconstruction efforts was estimated between US$1.2–2 million.[11][16]

Within the Paiti-la-Tonuatua area to the north of Noumea, New Caledonia Air Force helicopters rescued several people who had moved to the roofs of their houses.[36] Despite the severe crop damage, no areas were declared disasters by January 20. The South Pacific division of the Adventist Development and Relief Agency sent AU$5 thousand to New Caledonia for relief efforts.[10][26] Emergency funding of F300 thousand was given to New Caledonia to help with the relief effort by the French Minister of the Interior and Minister of Overseas Territories.[37] The European Commission also provided New Caledonia with €85 thousand, which was distributed by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in the form of cash donations to the worst-affected families.[38] After the season, the name "Anne" was retired by the World Meteorological Organization.[39]

See also

- Cyclone Agi

- Typhoon Roy

References

- Kishore, Satya; Fiji Meteorological Service (1988). DeAngellis, Richard M (ed.). Tropical Cyclone Anne (Mariners Weather Log: Volume 32: Issue 3: Summer 1988). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 33–34. hdl:2027/uiug.30112104094005. ISSN 0025-3367. OCLC 648466886. Archived from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- Darwin Regional Specialised Meteorological Centre (1988). "January 1988" (PDF). Darwin Tropical Diagnostic Statement. Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 7 (1): 2. ISSN 1321-4233. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- "1988 Tropical Cyclone ANNE (1988006S05182)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- Reese, Kenneth W; Joint Typhoon Warning Center; Naval Pacific Meteorology and Oceanography Center. Chapter III — Summary of Western North Pacific Ocean and North Indian Ocean Tropical Cyclones: Typhoon Roy (01W) (PDF) (1988 Annual Tropical Cyclone Report). United States Navy, United States Air Force. pp. 29–30. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Camplin, J (January 12, 1988). "Cyclone Threat as Anne moves in". Daily Telegraph. Sydney, Australia. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center; Naval Pacific Meteorology and Oceanography Center. Chapter IV — Summary of South Pacific and South Indian Ocean Tropical Cyclones (PDF) (1988 Annual Tropical Cyclone Report). United States Navy, United States Air Force. pp. 160–167. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Foley, G R. "The Australian Tropical Cyclone Season 1987–88" (PDF). Australian Meteorological and Oceanographic Journal. Australian Bureau of Meteorology (36): 205–212. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 9, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- Barstow, Stephen F; Haug, Ola (November 1994). The Wave Climate of Tuvalu (PDF) (SOPAC Technical Report 203). South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission. p. 13. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 26, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- Radford, Deirdre A; Blong, Russell J (1992). Natural Disasters in the Solomon Islands (PDF). 1 (2 ed.). The Australian International Development Assistance Bureau. pp. 125–126. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, Marshall Islands: Tropical Cyclone Anne (UNDRO Information Report Numbers 1–3). United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. January 20, 1988. Archived from the original on May 25, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- Tropical cyclones in Vanuatu: 1847 to 1994 (Report). Vanuatu Meteorological Service. May 19, 1994. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 18, 2010. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- "New Zealand, Australia continue aid to cyclone-devastated Vanuatu". The Xinhua General Overseas News Service. January 20, 1988. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Cyclone havoc in Vanuatu". Sydney Morning Herald. Associated Press. January 12, 1988. p. 9. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- "Vanuatu Appeal for help after cyclone". Canberra Times. National Library of Australia. Reuters. January 13, 1988. p. 5. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- "Crisis for food after cyclone". Courier Mail. Australian Associated Press. January 16, 1988 – via Lexis Nexis.

- Government of Vanuatu (May 3, 2001). Country Presentation of the Government of Vanuatu: Programme of Action for the Development of Vanuatu, 2001–2010 (PDF). Third United Nations Conference on the least developed countries: Brussels, May 14–20, 2001. United Nations. p. 8. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- Barstow, Stephen F; Haug, Ola (November 1994). The Wave Climate of Vanautu (PDF) (SOPAC Technical Report 202). South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 26, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- "Vanuatu hit by cyclone". Xinhua General Overseas News Service. January 12, 1988.

- Report of the WMO Post-Tropical Cyclone "Pam" Expert Mission to Vanuatu (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. p. 22.

- Reuters (January 14, 1988). "Two killed as Cyclone lashes New Caledonia". Sydney Morning Herald. p. 10. Archived from the original on April 25, 2013. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- "Two die in Cyclone". The Age. Reuters. January 14, 1988. p. 6.

- "Weather events in 1988 and their consequences". WMO Bulletin. World Meteorological Organisation. 38 (4): 296-297. 1989. ISSN 0042-9767. LCCN 56043713.

- New Caledonia Meteorological Office. "Phénomènes ayant le plus durement touché la Nouvelle-Calédonie: De 1880 à nos jours: Anne" [Phenomena having the hardest hit New Caledonia: From 1880 to the present: Anne]. Météo-France. Retrieved December 24, 2015.

- "Pacific typhoon kills 2 injuries 80". The Reading Eagle. Reuters. January 13, 1988. p. 2.

- "New Caledonia 2 drown, 80 hurt in Cyclone Anne". The Canberra Times. National Library of Australia. January 14, 1988. p. 5. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- Coffin, James, ed. (February 27, 1988). "Anne causes havoc" (PDF). Record. The South Pacific Division of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church. 97 (7). ISSN 0819-5633. OCLC 226264581.

- "La Dieppoise" (in French). Patrimoire Maritime de Nouvelle-Calédonie. Archived from the original on October 30, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- "The "Dieppoise" wreck". New Caledonia Diving. May 15, 2009. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- "Naval Mobile Construction Battalion 133: Historical Information" (PDF). Naval History and Heritage Command. July 20, 2010. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 25, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense. "Chapter 6.9 – DoD Service Medals: Humanitarian Service Medal". Manual of Military Decorations and Awards. United States Department of Defense. p. 171. Archived from the original on May 25, 2013. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- Barbour County (LST 1195) – Naval Cruise Book – Class of 1988. United States Navy. 1988.

- "In Brief: Cyclone Aid". The Age. Melbourne, Australia. January 18, 1988. p. 3. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- "The Nation: Hercules assists". Australian Financial Review. January 13, 1988. p. 4. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Regular Shorts: $1M aid for Cyclone area". Sydney Morning Herald. January 18, 1988. p. 8. Archived from the original on May 25, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- "Emergency Aid in favour of the Central African Republic, Vanuatu and Uganda" (Press release: IP-88-86). The European Union. February 22, 1988. Archived from the original on May 25, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- Pacific Islands Monthly: February 1988. 59. Pacific Publications. 1988. p. 22.

- "Aide aux victimes du cyclone Anne". Le Monde (in French). January 24, 1988. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- "Emergency Aid for New Caledonia" (Press release: IP-88-116). The European Union. March 1, 1988. Archived from the original on May 25, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- RA V Tropical Cyclone Committee (October 11, 2018). Tropical Cyclone Operational Plan for the South-East Indian Ocean and the Southern Pacific Ocean 2018 (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. pp. I-4–II-9 (9–21). Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

External links

- World Meteorological Organization

- Australian Bureau of Meteorology

- Fiji Meteorological Service

- New Zealand MetService

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center

- Track Map of Cyclone Anne near Vanuatu, from the Vanuatu Meteorological Service.