Criticism of fast food

Criticism of fast food includes claims of negative health effects, animal cruelty, cases of worker exploitation, children targeted marketing and claims of cultural degradation via shifts in people's eating patterns away from traditional foods. Fast food chains have come under fire from consumer groups, such as the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a longtime fast food critic over issues such as caloric content, trans fats and portion sizes. Social scientists have highlighted how the prominence of fast food narratives in popular urban legends suggests that modern consumers have an ambivalent relationship (characterized by guilt) with fast food, particularly in relation to children.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Human body weight |

|---|

|

Measurements |

|

Related conditions |

Some of these concerns have helped give rise to the slow food and local food movements. These movements seek to promote local cuisines and ingredients, and directly oppose laws and habits that encourage fast food choices. Proponents of the slow food movement try to educate consumers about what its members consider the environmental, nutritional, and taste benefits of fresh, local foods.

Health based criticisms

.jpg)

Many fast foods are rich in calories as they include considerable amounts of mayonnaise, cheese, salt, fried meat, and oil, thus containing high fat content (Schlosser). Excessive consumption of fatty ingredients such as these results in unbalanced diet. Proteins and vitamins are generally recommended for daily consumption rather than large quantities of carbohydrates or fat. Due to their fat content, fast foods are implicated in poor health and various serious health issues such as obesity and cardiovascular diseases. Additionally, there is strong empirical evidence showing that fast foods are also detrimental to appetite, respiratory system function,[2] and central nervous system function (Schlosser). In a cross-sectional data study from more than 100-thousand adolescents in 32 countries, which included low-income, middle-income, to high-income countries, it has been found that fast food is associated with increased attempt to suicide.[3][4]

According to the Massachusetts Medical Society Committee Jeff Nutrition, fast foods are commonly high in fat content, and studies have found associations between fast food intake and increased body mass index (BMI) and weight gain.[5] In particular many fast foods are high in saturated fats which are widely held to be a risk factor in heart disease.[6] In 2010, heart disease was the number 1 ranking cause of death.[7] A 2006 study[8] fed monkeys a diet consisting of a similar level of trans fats as what a person who ate fast food regularly would consume. Both diets contained the same overall number of calories. It was found that the monkeys who consumed higher levels of trans fat developed more abdominal fat than those fed a diet rich in unsaturated fats. They also developed signs of insulin resistance, an early indicator of diabetes. After six years on the diet, the trans fat fed monkeys had gained 7.2% of their body weight, compared to just 1.8% in the unsaturated fat group. A five-year study conducted in Singapore showed that frequent fast food consumers (more than 2 time per week) had a significant increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes and an increased risk of death rate from coronary heart disease, when compared to non-consumers.[9] The American Heart Association recommends consumption of about 16 grams of saturated fats a day.[10]

The director of the obesity program for the Children's Hospital Boston, David Ludwig, says that "fast food consumption has been shown to increase caloric intake, promote weight gain, and elevate risk for diabetes". Excessive calories are another issue with fast food. According to B. Lin and E. Frazao, from the US Department of Agriculture(USDA), the percentage of calories which can be attributed to fast-food consumption has increased from 3% to 12% of the total calories consumed in the United States.[11] A regular meal at McDonald's consists of a Big Mac, large fries, and a large Coca-Cola drink amounting to 1,430 calories. The USDA recommends a daily caloric intake of 2,700 and 2,100 kcal (11,300 and 8,800 kJ) for men and women (respectively) between 31 and 50, at a physical activity level equivalent to walking about 1.5 to 3 miles per day at 3 to 4 miles per hour in addition to the light physical activity associated with typical day-to-day life,[12] with the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety guidance suggesting roughly the same levels.[13]

However, besides fast food consumption, there are many other the other reasons for over weighting among children while they are growing, including sex development, "hormonal changes," and social interactions. At those moments kids can feel depressed, which may lead to increase or decrease in appetite. In fact, increased hunger may lead to obesity in some cases. “…seasonal effective disorder affects 1.7 – 5.5% of youths ages 9-19 years old based on a community study of over 2,000 youth."[14]

The fast food chain D'Lites, founded in 1978, specialized in lower-calorie dishes and healthier alternatives such as salads. It filed for bankruptcy in 1987 as other fast food chains began offering healthier options.[15] McDonald's has been attempting to offer healthier options besides salads. They have incorporated fruit and milk as options of happy meals and have promoted healthier ads and packaging for kids. The Alliance for a Healthier Generation has set a standard in hopes of pressuring fast food companies to make recommended healthier adjustments.[16]

Food poisoning risk

Besides the risks posed by trans fats, high caloric intake, and low fiber intake, another cited health risk is food poisoning. In his book Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal, Eric Schlosser argues [17] that meatpacking factories concentrate livestock into feedlots and herd them through processing assembly lines operated by employees of various levels of expertise, some of which may be poorly trained, increasing the risk of large-scale food poisoning.[18]

Manure on occasion gets mixed with meat, possibly contaminating it with salmonella and pathogenic E. coli. Usually spread through undercooked hamburgers, raw vegetables, and contaminated water, it is difficult to treat. In 2008, the Health Protection Agency in England showed that in a Salmonella Typhimurium infection of 179 cases, consumption of pre-packaged egg sandwiches was associated with illness.[19] Although supportive treatment can substantially aid inflicted individuals, since endotoxin is released from gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli upon death, antibiotic use to treat E. coli infections is not recommended.[20] About 4% of people infected with E. coli 0157:H7 develop hemolytic uremic syndrome, and about 5% of children who develop the syndrome die. The rate of developing HUS is 3 in 100,000 or 0.003%. E. coli 0157:H7 has become the leading cause of renal failure among American children.[18] These numbers include rates from all sources of poisoning, including lettuce; radish sprouts; alfalfa sprouts; unpasteurized apple juice/cider; cold cooked or undercooked meat; and unpasteurized animal milk. Additional environmental sources include fecal-contaminated lakes, nonchlorinated municipal water supply, petting farm animals and unhygienic person-to-person contact.[21] An average of sources leads to the number of 0.00000214% for undercooked beef.

Food-contact paper packaging

Fast food often comes in wrappers coated with polyfluoroalkyl phosphate esters (PAPs) to prevent grease from leaking through them. These compounds are able to migrate from the wrappers into the packaged food.[22] Upon ingestion, PAPs are subsequently biotransformed into perfluorinated carboxylic acids (PFCAs), compounds which have long attracted attention due to their detrimental health effects in rodents and their unusually long half-lives in humans. While epidemiological evidence has not demonstrated causal links between PFCAs and these health problems in humans, the compounds are consistently correlated with high levels of cholesterol and uric acid, and PAPs as found on fast food packaging may be a significant source of PFCA contamination in humans.[22][23][24]

Fast food and diet

On average, nearly one-third of U.S. children aged 4 to 19 eat fast food on a daily basis. Over the course of a year this is likely to result in a child gaining 6 extra pounds every year.[25] In a research experiment published in Pediatrics, 6,212 children and adolescents ages 4 to 19 years old were examined to extrapolate some information about fast food. Upon interviewing the participants in the experiment, it was reported that on any given day 30.3% of the total sample had eaten fast food. Fast-food consumption was prevalent in both males and females, in all racial/ethnic groups, and in all regions of the country.[26]

Additionally, in the study children who ate fast food, compared to those who did not, tended to consume more total fat, carbohydrates, and sugar-sweetened beverages. Children who ate fast food also tended to eat less fiber, milk, fruits, and non-starchy vegetables. After reviewing these test results, the researchers concluded that consumption of fast food by children seems to have a negative effect on an individual's diet, in ways that could significantly increase the risk for obesity.[26] Due to having reduced cognitive defenses against marketing, children may be more susceptible to fast food advertisements, and consequently have a higher risk of becoming obese.[27] Fast food is only a minuscule factor that contributes to childhood obesity. A study conducted by researchers at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill's Gillings School of Global Public Health showed that poor diet and obesity as an overall factor are the leading causes of rising obesity rates in children. "While reducing fast-food intake is important, the rest of a child's diet should not be overlooked," Jennifer Poti, co author and doctoral candidate in the university's Department of Nutrition. [28]

Contrary evidence has been documented that questions the correlation of a fast food diet and obesity. A 2014 People Magazine article recounts the experience of John Cisna, a science teacher at Colo-NESCO High School, who ate a fast food diet for 90 days. At the end of 90 days he had lost 37 pounds and his cholesterol level went from 249 to 170. Cisna kept to a strict 2,000 calorie limit a day and walked 45 minutes a day. Harley Pasternak, a celebrity trainer and nutrition expert, supports Cisna's experiment by saying, "While I don’t think it’s a great idea to eat too much fast food...I do think he is right. Fast food, while far from healthy, doesn’t make people gain weight. Eating too much fast food too often is what can make you gain weight—the same way eating too much of anything can pack on the pounds." [29] A cross-sectional study in China shows that the relationship between BMI and times per week fast food consumption was not significant.[30]

Jared Fogle’s drastic weight loss on a Subway diet, which is considered a fast food chain, is another case that poses a fair debate against the idea that the culprit of obesity is fast food. Fogle dropped 235 pounds by consuming Subway sandwiches for lunch and dinner daily. With no cheese or mayonnaise, the calories of both sandwiches totaled less than 1,000 calories in a day.[31]

Fast food labels without the calorie amount increase the risks of obesity. In the article of M. Mclnerney et al. is examined the impact of fast food labeling on college students’ overweighting. In the study the students required to label the calories of fast foods in the items’ lists. The results showed positive effects on the decreased significance of weighting among college students.[32] Thus, fast food restaurants need to write down the exact calories of the products to inform the consumers about their food choices in order to prevent overweight.

Fast food commercials

A 2012, estimated report by the US Federal Trade Commission revealed a $7.9 billion marketing expenditure difference between expenditure on marketing to all audiences and expenditure on marketing strictly to children and adolescents. According to this report, Fast food industries spent approximately $9.7 billion on marketing food and beverages to the general audience while they spent only $1.8 billion on marketing to children and adolescents.[33]

Consumer responsibility

Spokespeople for the fast food industry claim that there are no good or bad foods, but instead there are good or bad diets. The industry has defended itself by placing the burden of healthy eating on the consumer, who freely chooses to consume their product outside of what nutritional recommendations allow.[34]

Many fast food restaurants added labels to their menus by listing the nutritional information below each item. The intent was to inform consumers of the caloric and nutritional content of the food being served there and result in directing consumers to the healthier options available. However, reports do not display any significant drop in sales at sandwich or burger locations which highlights no change in consumer behavior even after food was labeled.[35]

Fast food is also affordable on people's incomes and expenses relating to the regions they live. "Healthy foods including whole-grain products, low-fat dairy foods, and fresh fruits and vegetables may be less available, and relatively costlier, in poor and minority neighborhoods."[36] So, fast food stores are located in the areas where the demand by the population is high.

Some other studies show that eating fast food is not dependent on a person's income. Researchers found that an amount of fast food consumed does not correlate with a person’s income level. The article "Wealth doesn't equal health Wealth: Fast food consequences not just for poor," discusses the issue: not all rich people are healthy food consumers, nor do they consume fast food less frequently than poor people. Additionally, fast food customers work harder and longer than those who do not eat fast food daily.[37] So, it is dependent on a person to choose their meal based on their lifestyle.

A study conducted in 20 Fast Food restaurants in Australia showed that despite the availability of healthy meal options on the menu less than 3% of the consumers observed opted for a healthy meal which emulated results of other recent Australian research on consumption of healthy meals at Fast Food locations. In this 12 hour observational study, about 34% of meals purchased were take-away, meals that were excluded from the study, and 65% represented the unhealthy eat-in meals while the remaining 1% represented the healthy meals purchased.[38]

Restrained eating, or excessive consumption of fast food and other unhealthy foods high in sugar and sodium, is a category of different eating habits derived from results of a cross-sectional study in 2014. This study depicted a prominent association between restrained eating and nurses working overnight shifts and those who are under high stress. Fruits and vegetables were reported as the least likely to be consumed under stress. About 395 nurses participated in this study. All these nurses were employees of two major hospitals in the capital city, Riyadh, of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.[39]

The research gathered from a nationwide study in China strictly concentrated on the link between fast food consumption and the growing obesity epidemic in children, ranging from ages 6–18. Although end results weren't completely inconclusive, there was no significant relationship found between the said two parties. The variables taken into consideration to support and narrow the study, displayed that with the presence of any of the following variables low-income households, peer influence, geographical location, pocket money and independence, fast food consumption rates increased. Fast food consumption rates escalated when older children were surveyed whilst consumption rates for younger children appeared normal. Also, western fast food was preferred by children of all ages because they associated western fast food with high quality food.[40]

"The McLawsuit" was a group of overweight children that filed a class action lawsuit against McDonald's seeking compensation for obesity related reasons.[41]

The CSR Halo Effect

The Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Effect is a phrase used to judge a category based on judgments from other similar categories or is in relation to them.[42] To put it in terms of the fast food industry, a customer who had a bad experience at a McDonald's would associate that experience with other McDonald's, casting a per-conspired image in their mind of how all other Mcdonald's are. Ioannis Assiouras states that "positive prior CSR leads to higher sympathy and lower anger and schadenfreude toward the company, than negative prior CSR or lack of CSR information." [42]

Worker discrepancies and strikes

Many fast food employees are adults who earn minimum wage, which in the United States is around $7.25 for every hour.[43] Around 60% of fast food workers are twenty-five years and older.[44][45]

Many employees have protested to raise the minimum wage. On December 5, 2013, protesters from 100 cities in the United States held demonstrations for a $15 hourly wage.[46] This protest was one of a series of strikes that began 2012, in New York City, protesting against low wages.[47]

There has been a study over employee wages at the fast food companies, the study suggests the fast food industry needs to increase an hourly payment from "7.25 to 10.25" for the beginners of the job. Besides, they recommend to rise that to 5 dollars after few years of experience.[48] From that it is clear to understand that how increased minimum wages has its effects on employees services, life style, and well being. Because workers start to work better when their life style changes as well as their payments.

Packaging waste

A 2011 study of litter in the Bay area by Clean Water Action found that nearly half of the litter present on the streets was fast food packaging. The Natural Resources Defense Council's paper “Waste and Opportunity 2015: Environmental Progress and Challenges in Food, Beverage, and Consumer Goods Packaging” reported that no fast food brands were meeting best practices for use of recycled materials or promotion of recycling of the used packaging. The EPA states that only a tiny proportion of the plastic waste generated by the fast food industry is recycled.[49]

Disposable Tableware as a Business Model

The use of disposable tableware shifts costs from in-house employment to the municipal waste stream. By convincing consumers to bus disposable tableware, mostly in the 1960-1975 time period, formula fast food restaurants were able gain competitive advantage over full-service lunch counter operations, despite the additional cost of the disposable items. Some attempts[50][51] at discouraging this have been made, but the custom of busing disposable items is still widespread. Other measures include "Carryout Bag" laws[52] and restrictions on formula restaurants.[53][54]

Fast food industry's response to criticism

John Merritt, senior vice president of public affairs for Hardee’s says their "strategy is not necessarily to move towards healthier items" but "to move towards more choice." [55]

In 2013, McDonald’s and Dunkin’ Brands publicly pledged to transition out of their use of foam hot beverage cups. McDonald’s has replaced foam with paper cups, but Dunkin’ has not initiated transition. The use of foam cups can still be seen at Chick-fil-A, Burger King, and KFC. Chipotle uses aluminum meal lids that are made from 95% recycled material, but they do not have postconsumer recycling, so the lids that are left on-site are landfilled.[56]

Animal cruelty

In 2015, a gruesome video clip of a T&S farm in Dukedom, Tennessee was released by animal rights activists, where workers were caught abusing chickens. Tyson Foods, the company which delivers chicken nuggets to the fast food giant McDonald's, cancelled their contract with the farm stating "animal well-being" is their utmost priority. McDonald's supported Tyson Foods' decision and described the workers actions as unacceptable.[57]

In the fall of 2007, an investigator working for the Humane Society of the United States documented inhumane treatment of downed dairy cows, those too weak to walk, at a slaughterhouse in Chino, California. Plant workers at the Hallmark/Westland facility were filmed using a forklift to forcibly move cows who could not rise to their feet, dragging them with chains, kicking them, spraying high-pressure water hoses into their nostrils and shocking them with electric prods, all in an effort to get them to stand long enough for the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) veterinary inspector to pass them for slaughter.[58]

Nutrition and health

In 2013, McDonald's announced that they would include fruits and vegetables in their menu combinations. Don Thompson, McDonald's chief executive stated, "We’ve been trying to optimize our menu with more fruits and vegetables and giving customers additional choices when they come to McDonald’s."[59]

In 2016 the company replaced the high-fructose corn syrup in its hamburger buns with sugar and removed antibiotics that are "important to human medicine" from its chicken. They also removed artificial preservatives from their cooking oil, pork sausage patties, eggs served on the breakfast menu, and Chicken McNuggets. The skin, safflower oil and citric acid from the McNuggets was also replaced with pea starch, rice starch and powdered lemon juice. These changes were made in an effort to target "health-conscious consumers."[60]

Source reduction

Many fast food chains have reduced their material usage by “lightweighting”, or reducing material in a package by weight. McDonald’s made over 10 reduction in packaging weight in 2012, such as a 48% reduction in the chicken sandwich paperboard carton, and an 18-28% reduction in its plastic cold cups. Starbucks has reduced their water bottle weight by 20% and cold cups by 15%.[56]

Cage-free hens

Over 160 companies in the food sector have announced that they are planning to shift to eggs from only cage-free hens, most by the year 2025. The list includes McDonald’s, Dunkin’ Donuts, Carl’s Jr., Burger King, Denny’s, Jack in the Box, Quiznos, Shake Shack, Starbucks, Sonic, Taco Bell, Wendy’s, White Castle, and Subway, among others. The full list can be seen at: https://web.archive.org/web/20170306143016/http://cagefreefuture.com/docs/Cage%20Free%20Corporate%20Policies.pdf [61]

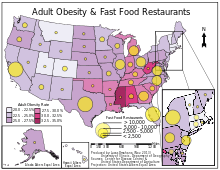

Proximity of fast food locations

A study of students who live within a half mile from fast food locations have been reported to consume fewer amounts of fruit and vegetables, consume more soda, and are more likely to be overweight.[62] More other studies show that the exposure to poor-quality food environments has important effects on adolescent eating patterns and overweight. Therefore, it seems that policy interventions limiting the proximity of fast-food restaurants to schools could help reduce adolescent obesity.[63]

See also

- Criticism of fast food advertising

- McDonaldization

References

- Robin Croft (2006), Folklore, families and fear: understanding consumption decisions through the oral tradition, Journal of Marketing Management, 22:9/10, pp1053-1076, ISSN 0267-257X

- Sharon Kirkey. “Fast Food May Be Linked to Higher Asthma Rates; Researchers Look for Triggers of Respiratory Affliction.” Edmonton Journal, Edmonton Journal, Jan. 2009.

- "Researchers at Anglia Ruskin University Target Affective Disorders (Fast Food Consumption and Suicide Attempts among Adolescents Aged 12-15 Years from 32 Countries)." Obesity, Fitness & Wellness Week, 2020, pp. 660.

- Jacob, Louis; Stubbs, Brendon; Firth, Joseph; Smith, Lee; Haro, Josep Maria; Koyanagi, Ai (2020-04-01). "Fast food consumption and suicide attempts among adolescents aged 12–15 years from 32 countries". Journal of Affective Disorders. 266: 63–70. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.130. ISSN 0165-0327. PMID 32056938.

- Block, J. P.; Scribner, R. A.; Desalvo, K. B. (2004). "Fast Food, Race/Ethnicity, and Income". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 27 (3): 211–7. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.007. PMID 15450633.

-

- Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation (2003). Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases (WHO technical report series 916) (PDF). World Health Organization. pp. 81–94. ISBN 978-92-4-120916-8. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- Kris-Etherton, PM; Innis, S; Dietetic Assocition, Ammerican; Dietetic Assocition, Ammerican (2007). "Position of the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada: Dietary Fatty Acids". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 107 (9): 1599.e1–1599.e15. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.024. PMID 17936958.

- "Food Fact Sheet – Cholesterol" (PDF). British Dietetic Association. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- "Frequently Asked Questions about Fats". American Heart Association. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- "Saturated Fat". Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- "Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors". Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- "Lower your cholesterol". National Health Service. 2018-04-26. Retrieved 2012-05-03. * "Nutrition Facts at a Glance – Nutrients: Saturated Fat". Food and Drug Administration. 2009-12-22. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- "Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for fats, including saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids, and cholesterol". European Food Safety Authority. 2010-03-25. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- "Name That Fast Food" New York Times, 17 December 1985. GALE. Web. 6 September 2013.

- "Why fast foods are bad, even in moderation".

- Duffey, Kiyah J (January 2013). "Greater intake of Western fast food among Singaporean adults is associated with increased risk of diabetes and heart-disease-related death". Evidence Based Nursing. 16 (1): 25–26. doi:10.1136/eb-2012-101006. ISSN 1367-6539. PMID 23100260.

- SaturatedFats.NHC.22 August 2013.Web.9 September 2013

- Block, Jason P.; Scribner, Richard A.; Desalvo, Karen B. (2004). "Fast Food, Race/Ethnicity, and Income: A Geographic Analysis". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 27 (3): 211–217. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.007. PMID 15450633.

- "Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion (CNPP) | USDA-FNS" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-27. Retrieved 2011-11-23.

- Reevis, Gloria M.; Postolache, Teodor T. (2008). "Childhood Obesity and Depression: Connection between These Growing Problems in Growing Children". International Journal of Child Health and Human Development. IJCHD 1.2 (2): 103–114. PMC 2568994. PMID 18941545.

- FIU Hospitality Review. 1988. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- Morrison, Maureen. "McD's vow to promote healthful menu options puts pressure on rivals; Fast-food leader says it will offer salads instead of fries with value meals and push milk and fruit for Happy Meals in industry watershed." Advertising Age 30 September 2013: 0006. General OneFile. Web. 22 November 2013.

- Schiosser E. Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin; 2001.

- "FDA issues letter to industry on foods containing botanical and other novel ingredients". US Food and Drug Administration. February 5, 2001. Archived from the original on July 31, 2009. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

- Boxall, N. S.; Adak, G. K.; De Pinna, E.; Gillespie, I. A. (December 2011). "A Salmonella Typhimurium phage type (PT) U320 outbreak in England, 2008: continuation of a trend involving ready-to-eat products". Epidemiology and Infection. 139 (12): 1936–1944. doi:10.1017/S0950268810003080. ISSN 0950-2688. PMID 21255477.

- "E. coli treatment". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- Razzaq, Samiya (2006-09-15). "Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome: An Emerging Health Risk". American Family Physician. 74 (6): 991–996. PMID 17002034. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- D'eon JC, Mabury SA (2010). "Exploring Indirect Sources of Human Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Carboxylates (PFCAs): Evaluating Uptake, Elimination and Biotransformation of Polyfluoroalkyl Phosphate Esters (PAPs) in the Rat". Environ Health Perspect. 119 (3): 344–350. doi:10.1289/ehp.1002409. PMC 3059997. PMID 21059488.

- Steenland K, Fletcher T, Savitz DA (2010). "Epidemiologic Evidence on the Health Effects of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA)". Environ. Health Perspect. 118 (8): 1100–8. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901827. PMC 2920088. PMID 20423814.

- Schlosser, Eric. Fast food nation: The dark side of the all-American meal. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=dU13X_AM_N8C&oi=fnd&pg=PP2&dq=fast+food&ots=DnPkOK3oKl&sig=_XtoQIQbakFGInAVJF1I7CYuYYk#v=onepage&q=fast%20food&f=false

- "Fast Food Linked To Child Obesity". 5 January 2004. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- "Effects of fast-food consumption on energy intake and diet quality among children in a national household survey." Pediatrics 113.1 (2004): 112-118. E-Journals. EBSCO. Web. 27 Oct. 2014.

- Brownell, Kelly. "In Your Face: How The Food Industry Drives Us To Eat." Nutrition Action Health Letter 37.4 (2010):3. MasterFILE Premier. Web. 10 September 2013.

- Poti, J. M.; Duffey, K. J.; Popkin, B. M. (2013). "The association of fast food consumption with poor dietary outcomes and obesity among children: is it the fast food or the remainder of the diet?". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 99 (1): 162–171. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.071928. PMC 3862453. PMID 24153348.

- Pasternak, Harley. "Harley Pasternak: Can You Lose Weight Eating Fast Food?" People, GreatIdeas. 08 Jan. 2014. Web. 26 Mar. 2014.

- Ma, R., D. C. Castellanos, and J. Bachman. "Identifying Factors Associated with Fast Food Consumption among Adolescents in Beijing China using a Theory-Based Approach." Public Health, vol. 136, 2016, pp. 87-93.

- Downs, Julie (October 2013). "Does "Healthy" Fast Food Exist? The Gap Between Perceptions and Behavior". Journal of Adolescent Health. 53 (4): 429–430. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.005. PMID 24054077.

- McInerney, M; Hutchins, M (September 2017). "Menu Labels Decrease the Number of Calories Selected from Fast-food Restaurants among College Students: A Pilot Study". Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 117 (9): A90. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2017.06.075.

- McClure, Auden (November 2013). "Receptivity to Television Fast-Food Restaurant Marketing and Obesity Among U.S. Youth". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 45 (5): 560–568. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.011. PMC 3934414. PMID 24139768.

- Brownell, Kelly."In Your Face: How The Food Industry Drives Us to Eat."Nutrition Action Health Letter 37.4(2010):3.MasterFILE Premier. Web. 10 September 2013.

- Downs, Julie (October 2013). "Does "Healthy" Fast Food Exist? The Gap Between Perceptions and Behavior". Journal of Adolescent Health. 53 (4): 429–430. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.005. PMID 24054077.

- Newman, Beyron Y. (2006). ". "Health Versus Fast Food Locations."". Optometry - Journal of the American Optometric Association. 77 (6): 258. doi:10.1016/j.optm.2006.03.013.

- "Wealth doesn't equal health Wealth: Fast food consequences not just for poor". Business Insights: Essentials. Spring 2018.

- Wellard, Glasson, Chapman, Lyndal, Colleen, Kathy (April 2012). "Sales of healthy choices at fast food restaurants in Australia". Health Promotion Journal of Australia. 23 (1): 37–41. doi:10.1071/he12037. PMID 22730936. ProQuest 1011639552.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Almajwal, Ali (February 2016). "Stress, shift duty, and eating behavior among nurses in Central Saudi Arabia". Saudi Medical Journal. 37 (2): 191–8. doi:10.15537/smj.2016.2.13060. PMC 4800919. PMID 26837403.

- Hong, Xue (March 2016). "Time Trends in Fast Food Consumption and Its Association with Obesity among Children in China". PLOS ONE. 11 (3): e0151141. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1151141X. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0151141. PMC 4790849. PMID 26974536. ProQuest 1773263068.

- Mello, Michelle M.; Rimm, Eric B.; Studdert, David M. (November 2003). "The McLawsuit: The Fast-Food Industry And Legal Accountability For Obesity". Health Affairs. 22 (6): 207–216. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.22.6.207. ISSN 0278-2715. PMID 14649448.

- Assiouras, Ioannis. "Join Academia.edu & Share Your Research with the World." THE EFFECT OF CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY ON CONSUMERS' EMOTIONAL REACTIONS IN PRODUCT-HARM CRISIS. N.p., 2011. Web. 31 Jan. 2014.

- Jablon, Eden. "Understanding the Fast-Food Minimum Wage Debate – Food". The Wesleyan Argus. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- "Slow Progress for Fast-Food Workers" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- "Bill Maher: Average fast food worker is 29, most are on public assistance | PunditFact". Politifact.com. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- "Charts: Why Fast-Food Workers Are Going on Strike". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- Mantel, Barbara. "Minimum Wage." CQ Researcher. 04 Jan. 2014. Web. 03 Feb. 2014.

- Pollin, Robert; Wicks-Lim, Jeannette (September 2016). "A $15 U.S. Minimum Wage: How the Fast-Food Industry Could Adjust Without Shedding Jobs". Journal of Economic Issues. 50 (3): 716–744. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.675.1509. doi:10.1080/00213624.2016.1210382.

- MacKerron, Conrad B. "Waste and Opportunity 2015: Environmental Progress and Challenges in Food, Beverage, and Consumer Goods Packaging". Rep. no. R:15-01-A. N.p.: NRDC, 2015. Print.

- "Don't Bus Throw-Away Utensils and Tableware", skoozeme.com

- "Be straw free campaign"

- "Bring your bag" information, Dept. of Environmental Protection, Montgomery Cty., Maryland, US

- Formula Business Restrictions, Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR)

- Analysis of Cities with Formula Business Ordinances, Malibu, California (.pdf)

- Clark, Charles S. "Fast-Food Shake-up." CQ Researcher. 08 Nov. 1991. Web. 03 Feb. 2014.

- MacKerron, Conrad B. Waste and Opportunity 2015: Environmental Progress and Challenges in Food, Beverage, and Consumer Goods Packaging. Rep. no. R:15-01-A. N.p.: NRDC, 2015. Print.

- Tolliver, Whitecomb; Jonathan, Dan (August 27, 2015). "McDonald's, Tyson Foods drop farm after videotape shows animal cruelty". Reuters.

- Shields, Sara; Shapiro, Paul; Rowan, Andrew (2017-05-15). "A Decade of Progress toward Ending the Intensive Confinement of Farm Animals in the United States". Animals. 7 (12): 40. doi:10.3390/ani7050040. ISSN 2076-2615. PMC 5447922. PMID 28505141.

- Strom, Stephanie (26 September 2013). "With Tastes Growing Healthier, McDonald's Aims to Adapt Its Menu". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- "McDonald's to remove corn syrup from buns, curbs antibiotics in chicken". Reuters. 2016-08-01. Retrieved 2017-04-16.

- Strom, Stephanie. "McDonald's Plans a Shift to Eggs From Only Cage-Free Hens." The New York Times. The New York Times, 9 September 2015. Web. 5 March 2017.

- Davis, Brennan; Carpenter, Christopher (March 2009). "Proximity of Fast-Food Restaurants to Schools and Adolescent Obesity". American Journal of Public Health. 99 (3): 505–510. doi:10.2105/ajph.2008.137638. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 2661452. PMID 19106421.

- Davis, Brennan, and Christopher Carpenter. "Proximity of Fast-Food Restaurants to Schools and Adolescent Obesity." American Journal of Public Health, vol. 99, no. 3, 2009, pp. 505-510.