Crematorium

A crematorium or crematory is a venue for the cremation of the dead.

.jpg)

Modern crematoria contain at least one cremator (also known as a crematory, retort or cremation chamber), a purpose-built furnace. In some countries a crematorium can also be a venue for open-air cremation. In many countries, crematoria contain facilities for funeral ceremonies, such as a chapel. Some crematoria also incorporate a columbarium, a place for interring cremation ashes.

Ceremonial facilities

While a crematorium can be any place containing a cremator, modern crematoria are designed to serve a number of purposes. As well as being a place for the practical but dignified disposal of dead bodies, they must also serve the emotional and spiritual needs of the mourners.[1]

The design of a crematorium is often heavily influenced by the funeral customs of its country. For example, crematoria in the United Kingdom are designed with a separation between the funeral and cremation facilities, as it is not customary for mourners to witness the coffin being placed in the cremator. To provide a substitute for the traditional ritual of seeing the coffin descend into a grave, they each incorporated a mechanism for removing the coffin from sight. On the other hand, in Japan, mourners will watch the coffin enter the cremator, then will return after the cremation for the custom of picking the bones from the ashes.[1]

History

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, cremation could only take place on an outdoor, open pyre; the alternative was burial. In the 19th century, the development of new furnace technology and contact with cultures that practiced cremation led to its reintroduction in the Western world.[1]

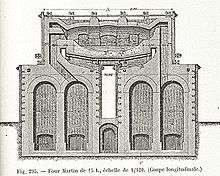

The organized movement to instate cremation as a viable method for body disposal began in the 1870s. In 1869 the idea was presented to the Medical International Congress of Florence by Professors Coletti and Castiglioni "in the name of public health and civilization". In 1873, Professor Paolo Gorini of Lodi and Professor Lodovico Brunetti of Padua published reports or practical work they had conducted.[2][3] A model of Brunetti's cremating apparatus, together with the resulting ashes, was exhibited at the Vienna Exposition in 1873 and attracted great attention, including that of Sir Henry Thompson, 1st Baronet, a surgeon and Physician to the Queen Victoria, who returned home to become the first and chief promoter of cremation in England.[4]

Meanwhile, Sir Charles William Siemens had developed his regenerative furnace in the 1850s. His furnace operated at a high temperature by using regenerative preheating of fuel and air for combustion. In regenerative preheating, the exhaust gases from the furnace are pumped into a chamber containing bricks, where heat is transferred from the gases to the bricks. The flow of the furnace is then reversed so that fuel and air pass through the chamber and are heated by the bricks. Through this method, an open-hearth furnace can reach temperatures high enough to melt steel, and this process made cremation an efficient and practical proposal. Charles's nephew, Carl Friedrich von Siemens perfected the use of this furnace for the incineration of organic material at his factory in Dresden. The radical politician, Sir Charles Wentworth Dilke, took the corpse of his dead wife there to be cremated in 1874. The efficient and cheap process brought about the quick and complete incineration of the body and was a fundamental technical breakthrough that finally made industrial cremation a practical possibility.[5]

The first crematorium in the West opened in Milan in 1876.[6][7] By the end of the 19th century, several countries had seen their first crematorium open. Golder's Green Crematorium was built from 1901 to 1928 in London and pioneered two features that would become common in future crematoria: the separation of entrance and exit, and a garden of remembrance.[1]

| Country | Location of first crematorium | Year opened | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crematorium Temple, Monumental Cemetery, Milan | 1876 | [6][7] | |

| LeMoyne Crematory, Washington County, Pennsylvania | 1876 | [8][9] | |

| Gotha | 1878 | [7] | |

| Woking Crematorium, Woking, Surrey | 1885 | [10] | |

| Stockholm | 1887 | [7] | |

| Zürich | 1889 | [7] | |

| Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris | 1889 | [7] |

Cremators

While open outdoor pyres were used in the past and are often still used in many areas of the world today, notably India, most cremation in industrialized nations takes place within enclosed furnaces designed to maximize use of the thermal energy consumed while minimizing the emission of smoke and odors.

Thermodynamics

A human body usually contains a negative caloric value, meaning that energy is required to combust it. This is a result of the high water content; all water must be vaporized which requires a very large amount of thermal energy.

A 68 kg (150 lbs) body which contains 65% water will require 100 MJ of thermal energy before any combustion will take place. 100 MJ is approximately equivalent to 3 m3 (105 ft3) of natural gas, or 3 liters of fuel oil (0.8 US gallons). Additional energy is necessary to make up for the heat capacity ("preheating") of the furnace, fuel burned for emissions control, and heat losses through the insulation and in the flue gases.

As a result, crematories are most often heated by burners fueled by natural gas. LPG (propane/butane) or fuel oil may be used where natural gas is not available. These burners can range in power from 150 to 400 kilowatts (0.51 to 1.4 million British thermal units per hour).

Crematories heated by electricity also exist in India, where electric heating elements bring about cremation without the direct application of flame to the body.

Coal, coke, and wood were used in the past, heating the chambers from below (like a cooking pot). This resulted in an indirect heat and prevented mixing of ash from the fuel with ash from the body. The term retort when applied to cremation furnaces originally referred to this design.

There has been interest, mainly in developing nations, to develop a cremator heated by concentrated solar energy.[11] Another new design starting to find use in India, where wood is traditionally used for cremation, is a cremator based around a wood gas fired process. Due to the manner in which the wood gas is produced, such crematories use only a fraction of the required wood; and according to multiple sources, have far less impact on the environment than traditional natural gas or fuel oil processes.[12]

Combustion system

A typical unit contains a primary and secondary combustion chamber. These chambers are lined with a refractory brick designed to withstand the high temperatures.

The primary chamber contains the body – one at a time usually contained in some type of combustible casket or container. This chamber has at least one burner to provide the heat which vaporizes the water content of the body and aids in combustion of the organic portion. A large door exists to load the body container. Temperature in the primary chamber is typically between 1,400–1,800 °C (2,550–3,270 °F) 871 and 982 °C (1600 to 1800 °F).[13] Higher temperatures speed cremation but consume more energy, generate more nitric oxide, and accelerate spalling of the furnace's refractory lining.

The secondary chamber may be at the rear or above the primary chamber. A secondary burner(s) fires into this chamber, oxidizing any organic material which passes from the primary chamber. This acts as a method of pollution control to eliminate the emission of odors and smoke. The secondary chamber typically operates at a temperature greater than 900 °C (1650 °F).

Air pollution control and energy recovery

The flue gases from the secondary chamber are usually vented to the atmosphere through a refractory-lined flue. They are at a very high temperature, and interest in recovering this thermal energy e.g. for space heating of the funeral chapel, or other facilities or for distribution into local district heating networks has arisen in recent years. Such heat recovery efforts have been viewed in both a positive and negative light by the public.[14]

In addition, filtration systems (baghouses) are being applied to crematories in many countries. Activated carbon adsorption is being considered for mercury abatement (as a result of dental amalgam). Much of this technology is borrowed from the waste incineration industry on a scaled-down basis. With the rise in the use of cremation in Western nations where amalgam has been used liberally in dental restorations, mercury has been a growing concern.

Automation

The application of computer control has allowed cremators to be more automated, in that temperature and oxygen sensors within the unit along with pre-programmed algorithms based upon the weight of the deceased allow the unit to operate with less user intervention. Such computer systems may also streamline recordkeeping requirements for tracking, environmental, and maintenance purposes.

Additional aspects

The time to carry out a cremation can vary from 70 minutes to 210 minutes. Cremators used to run on timers (some still do) and one would have to determine the weight of the body therefore calculating how long the body has to be cremated for and set the timers accordingly. Other types of crematories merely have a start and a stop function for the cremation displayed on the user interface. The end of the cremation must be judged by the operator who in turn stops the cremation process.[15][16]

As an energy-saving measure, some cremators provide heating for the building.[1]

References

- "Typology: Crematorium". Architectural Review. 14 November 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- Cobb, John Storer (1901). A Quartercentury of Cremation in North America. Knight and Millet. p. 150.

- "Brunetti, Lodovico" by Giovanni Cagnetto, Enciclopedia Italiana (1930)

- "Introduction". Internet. The Cremation Society of Great Britain. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- Alon Confino; Paul Betts; Dirk Schumann (2013). Between Mass Death And Individual Loss: The Place of the Dead in Twentieth-Century Germany. Berghahn Books. p. 94.

- Boi, Annalisa; Celsi, Valeria (2015). "The Crematorium Temple in the Monumental Cemetery in Milan". In_Bo. Ricerche e Progetti per Il Territorio. 6 (8). doi:10.6092/issn.2036-1602/6076.

- Encyclopedia of Cremation by Lewis H. Mates (p. 21-23)

- "The LeMoyne Crematory". Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- "An Unceremonious Rite; Cremation of Mrs. Ben Pitman" (PDF). The New York Times. 16 February 1879. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- The History Channel. "26 March – This day in history". Archived from the original on 30 December 2006. Retrieved 20 February 2007.

- "Development of a Solar Crematorium" (PDF).

- "Gasifier Based Crematorium,Wood Gasifier Based Crematorium,Biomass Gasifier Crematorium Exporters". www.gasifiers.co.in. Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- "How Is A Body Cremated?". Cremation Resource. US. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Nobel, Justin (24 May 2011). "New Life for Crematories' Waste Heat". Miller-McCune. Archived from the original on 29 August 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- Cremationprocess.co.uk Archived 25 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Ashes to Ashes: The Cremation Process Explained". www.everlifememorials.com.

External links