Cornwall Friends Meeting House

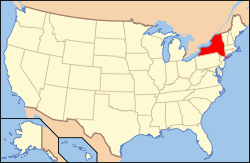

The Cornwall Friends Meeting House is a historic meeting house located on a 5.4-acre (2.2 ha) parcel of land at the junction of Quaker Avenue (Orange County 107) and US 9W in Cornwall, New York, United States, near Cornwall-St. Luke's Hospital. It is both the oldest religious building in the town, and the first one built.[1] In 1988 it was added to the National Register of Historic Places as a well-preserved, minimally-altered example of a late 18th-century Quaker meeting house.

Cornwall Friends Meeting House | |

South (front) elevation and west profile of meeting house in 2007 | |

| Location | Cornwall, NY |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Newburgh |

| Coordinates | 41°26′01″N 74°02′35″W |

| Area | 5.4 acres (2.2 ha)[1] |

| Built | 1790[1] |

| NRHP reference No. | 88002751 |

| Added to NRHP | 1988 |

Built in 1790, it emulates the doubled style of meeting house pioneered by Buckingham Friends Meeting House in Pennsylvania two decades earlier.[2] David Sands-Ring, a local convert to the Religious Society of Friends and the son of a wealthy landowner, sponsored the construction of the meeting house. At first a branch of the Nine Partners meeting near present-day Millbrook in Dutchess County, it later became an independent congregation within the Society. Members also maintain the Smith Clove Meetinghouse in Highland Mills to the south of Cornwall.

Property

The property consists of the meeting house, a carriage house and cemetery. All are considered contributing resources to the Register listing.

The meeting house itself is a two-and-a-half-story four-bay white clapboard structure, set amid tall oak trees and set back slightly from the street. It has a full porch on the south (front) elevation, where separate entrances project at either end. Rough-hewn post-and-beam framing supports the house on a stone foundation. The gabled roof has a slight overhang but no decoration. A one-story wing with brick chimney rising from its metal-shingled roof extends from the northeast corner.[1]

Inside, the main floor is divided into two rooms of equal size, with a removable partition between them, an original feature found in many Quaker meeting houses of the period. The western half, used for services, features plain white benches along every wall facing the center of the room, where a Bible sits on a small table. The benches along the northern wall, reserved for elders, are slightly elevated. The east room, used for meetings and social gatherings, has a piano, folding tables and chairs and a library of Quaker reading. Two original stairs lead up to the upper story, formerly a gallery that overlooked the lower rooms. Much of the original work, including the bare ceiling, remains. The northeast wing contains a kitchen and two bathrooms.[1]

The carriage house is located to the east of the meeting house. It is a five-bay open-front structure, built of pegged and hewn timber framing with vertical siding.[1] The structure is an early five-bay, open-front shed with pegged and hewn framing and vertical siding. The building is thirty-two feet east of the Meeting House, with the front of the open bays aligned with the back (or south) wall of the Meeting House. One of the bays has been enclosed for storage. The simple heart of this magnificent structure remains unmodified: massive posts and beams held together by hand-hewn pins. Along several of the supporting timbers, and on the far (east) wall, one can see evidence of restless horses’ gnawing on the wood. One may also see some century-old mischief, as children's pen-knives have left such marks as “GTC: 1877.”

The cemetery, located to the northwest of the meeting house, contains graves dating to 1799. Not all of the 771 entombed are Quakers, as the cemetery was not restricted to congregants and it was the only one in Cornwall at the time. Early tombstones are of sandstone, with later markers of marble, reflecting changing trends in the 19th century. Funerary art is absent from graves of Quakers, per the faith's preference for simplicity, and minimal on non-Quaker resting places. The only exceptions are three 19th century headstones in the Quaker section with carvings of flowers, all the graves of children, and some early 20th century granite stones. The Cemetery is an active part of the Cornwall Monthly Meeting, the operation of which is overseen by the Cemetery Committee of the Meeting. Interments continue to take place, both of Quakers and others to whom the site holds a special claim.[1]

History

Cornwall's Quaker meeting originated with David Sands-Ring, the American-born son of a Presbyterian family that had settled in the area, after a stop in Sands Point, Long Island, following the seizure of its English landholdings by the Crown for religious reasons. At the age of 14, in 1759, the spiritually curious boy found himself drawn to the local Quaker population, whose religious thinking was close to his own. Along with Edward Hallock, another displaced Long Islander from the nearby hamlet of New Marlborough (today's Marlboro), he began attending meetings at the Nine Partners Meeting House across the river. He was admitted to that meeting upon attaining adulthood and married Hallock's daughter. Eventually Sands-Ring converted his entire family to his new faith.[1]

Others in the area soon followed them, and in 1773 the Nine Partners meeting allowed Hallock and Sands-Ring to hold their own meetings, alternating between the two locations. The congregations continued to grow and three years later, in 1776, the Cornwall and New Marlborough meetings became separate "preparative meetings", their business still subject to Nine Partners' approval. The Revolutionary War displaced more Long Island Quakers to Cornwall, and in 1788 it became a self-governing meeting. The next year a 10-acre (4 ha) parcel was deeded to the meeting for its house, as the Sands-Rings' could no longer host the growing congregation.[1]

Meeting members directed the construction of the house in 1790, the first religious building in Cornwall.[1] Its exterior reflects contemporary trends in vernacular residential architecture; the interior arrangements were dictated by religious requirements. The Cornwall Meeting gave rise to preparative meetings of its own in the area, including Smith Clove, and Cornwall became its own Quarterly Meeting in 1816, ending its last tie with Nine Partners.[1]

The Cornwall Quaker community was almost 500 strong, including most of Cornwall's prominent families, in 1825, when it along with the entire American Society of Friends was torn by the schism resulting from the influence of Elias Hicks. He represented mainstream Quakers who kept to the Society's traditional forms of worship, while those who disagreed with him, the Orthodox Quakers, had moved toward practices typical of mainstream Protestantism, such as worshipping in churches under the direction of ministers. Hicks' supporters formed a majority of the Cornwall meeting, and the Orthodox, including the Sands family, left and built their own meeting house around 1829.[1]

Over the rest of the 19th century the Quakers assimilated more into mainstream culture. The renovations made to the Cornwall meeting house reflect this trend, with not only new clapboard going on but the porch replacing what had been separate entrance lobbies for men and women. In the 1920s the north wing, with its kitchen facility, was added and in the 1950s the building was equipped with electrical and plumbing service. The original design of the Meeting Room featured a gallery above the main floor that occupied the front and two sides of the upper floor. However, after a fire in 1978 a ceiling was constructed over the Meeting Room. With the exception of this ceiling, the carpeting, the cushions on the benches and the paint on the walls, the Meeting Room itself is unchanged from the day it was built in 1790.[1]

The doors on the extreme corners of the porch lead upstairs. The rare, slender stair rails, supported by square balusters, are distinctive from the late 1700s. The rail ends in a pronounced upturn. Along the walls may be seen New England-style tapered posts supporting the ceiling. These are called “gunstock” posts, due to their shape. The rough-hewn beams, over 200 years old, are visible from this room, as well as the original wood surrounding the windows.

References

- Kuhn, Robert (October 1988). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Cornwall Friends Meeting House". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- "Buckingham Friends Meeting House National Historic Landmark Application" (PDF). (166 KiB), retrieved August 1, 2007.