Capture of Chusan

The First Capture of Chusan by British forces in China occurred on 5–6 July 1840 during the First Opium War. The British captured Chusan (Zhoushan), the largest island of an archipelago of that name.

Background

The Kangxi Emperor established an administration in the Chusan (Zhoushan) archipelago after the wars against the Zhengs in Taiwan and Geng Jingzhong during the Revolt of the Three Feudatories. The civil administration of Dinghai County was based in Chusan Island, the largest of the archipelago. The Dinghai regional command (zhen) covered a military garrison with a biao of three water force brigades and a total of 2,600 troops. They also controlled a water force (xie) based in Xiangshan and two water force brigades based in Shipu and Zhenhai.[2] In 1684, Kangxi lifted the early Qing maritime trade ban (haijin), and Ningbo was designated as a foreign trading port. In 1698, port authorities established the "Red Hair House" at Dinghai, where they could receive British traders. The Qianlong Emperor banned the British from Ningbo in 1757 and Dinghai was closed to foreign trade. The British remained familiar with the place and continued to view it with profitable trading potential.[3]

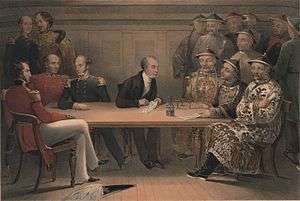

On 4 July 1840, the Wellesley, Conway, Alligator, and Rattlesnake arrived in the anchorage off Chusan harbour.[4] In the afternoon, Captain John Vernon Fletcher of the Wellesley, military secretary Lord Robert Jocelyn, and interpreter Karl Gützlaff were sent on board the junk of a Chinese admiral, who was also governor of the Chusan islands.[5][6] They delivered a written message from Commodore Gordon Bremer, commander-in-chief of the British naval forces, and Brigadier George Burrell, commander-in-chief of the land forces, to surrender the island of Chusan.[7] Bremer and Burrell claimed the occupation was necessary after the "insulting and unwarrantable conduct" of the Canton high officers Lin Zexu and Deng Tingzhen last year towards Chief Superintendent Charles Elliot and British subjects.[8] Part of the message stated:

If the inhabitants of the said islands do not oppose and resist our forces, it is not the intention of the British Government to do injury to their persons and property ... It is necessary for the safety of the British ships and troops that your Excellency should immediately surrender the island Tinghae, its dependencies and forts, and we therefore summon your Excellency to surrender the same peaceably, to avoid the shedding of blood. But if you will not surrender, we, the Commodore and Commander, shall be obliged to use warlike measures for obtaining possession.[8]

After an hour, Chinese Admiral Zhang Chaofa and other officials accompanied the British on board the Wellesley.[5][9] The Chinese objected to being made answerable for actions at Canton, saying, "those are the people you should make war upon, and not upon us who never injured you; we see your strength, and know that opposition will be madness, but we must perform our duty if we fall in so doing."[10] They were informed that hostilities would commence if submission was not made before daylight the next day.[4] Their last words before departing at 8:00 pm were: "If you do not hear from us before sunrise, the consequences be upon our own heads."[10][11] Commodore Bremer wrote that "gongs and other warlike demonstrations were audible" throughout the evening.[11]

Battle

On the morning of 5 July, a large number of Chinese troops occupied the hill and shore. British seamen from the masthead of the ships observed the city walls of Dinghai, which were 1 mile (1.6 km) from the beach, also lined with troops. At about 2:00 pm, the brigs Cruiser and Algerine got into position, and the signal was given to land.[4] The first division comprised the 18th Royal Irish Regiment, Royal Marines, the 26th Regiment, and two 9-pounder guns. The second division comprised the 49th Regiment, Madras Sappers and Miners, and Bengal Volunteers.[12] The British squadron consisted of the warships Wellesley, Conway, Alligator, Cruiser, and Algerine, the steamers Atlanta and Queen, and 10 gun-brigs or transport ships including the Rattlesnake.[11][13][14] According to Chinese accounts, 1,540 troops were stationed at Dinghai: 940 on board 21 war junks with a total of 170 cannon, while 600 were on shore with 20 cannon.[14] At 2:30 pm, the Wellesley fired at the Chinese fort resembling a Martello tower.[13] The Chinese immediately returned fire from the shore and junks. The British cannonade lasted 7–8 minutes before the Chinese troops fled to the city walls behind the suburbs.[11][15]

The British landed unopposed on a deserted beach, which Lord Jocelyn described as having "a few dead bodies, bows and arrows, broken spears and guns".[9] By 4:00 pm, British troops placed two 9-pounders within 400 yards (370 m) of the city walls. Six more 9-pounders, two howitzers, and two mortars were later added to the arsenal.[15] Brigadier Burrell waited until the next day before ordering a resumption of operations. The next morning, he sent a party to reconnoitre the city. Although there were thousands of inhabitants during the evening, the city was now largely abandoned. The gate was found strongly barricaded by large sacks of grain. A company of the 49th Regiment took possession of the main gate of the city, where the British flag was hoisted.[16]

The British, who only had one wounded,[15] captured 91 pieces of ordnance[5] and estimated the Chinese losses at 25 killed.[16] According to Imperial Commissioner Yukien, the Chinese casualties were 13 killed and 13 wounded, with Admiral Zhang having died from his wounds.[14] Lord Jocelyn wrote that Zhang was taken to Ningbo, opposite of the island, and "although honours were heaped upon him for his gallant, but unavailing defence", he died a few days later.[10] Zhang's costume was displayed at the National Museum of Scotland in 2017.[17]

Lord Jocelyn described his account of the city:

The main street was nearly deserted, except here and there, where the frightened people were performing the kow-tow as we passed. On most of the houses was placarded "Spare our lives;" and on entering the jos-houses were seen men, women, and children, on their knees, burning incense to the gods; and although protection was promised [to] them, their dread appeared in no matter relieved.[18]

Aftermath

On 8 July, Rear-Admiral George Elliot, joint plenipotentiary with his cousin Captain Charles Elliot, issued a proclamation from HMS Melville. He declared, among other things, that Chinese natives shall continue to be governed under Chinese laws (excluding torture), and that the "civil, fiscal, and judicial administration" of the Chinese government shall be exercised under the British officer in chief command of the land forces.[19] Brigadier Burrell became governor of Chusan, Gützlaff was made chief magistrate, and Lord Jocelyn was appointed military secretary to the admiral.[20]

Widespread sickness and mortality affected the troops who were in unsanitary conditions. Men were placed in tents pitched on low paddy fields surrounded by stagnant water. These moist, mosquito-ridden environments and lack of proper drainage helped spread malaria. Performing duties in a hot climate while wearing a coatee caused troops to become fatigued. Bad provisions, low spirits, and despondency led them to drink samshu, which increased their liability to disease.[21][22][23] On 22 October, only 2,036 out of 3,650 troops were fit for duty, the rest being sick or dead.[24] From 13 July to 31 December, there were 5,329 hospital admissions (including re-admissions) and 448 deaths. Half the admissions were for intermittent fever and two-thirds of the deaths were from diarrhoea and dysentery.[25] William Lockhart of the Medical Missionary Society established a hospital in Chusan, operating from 13 September to 22 February 1841.[26]

On 23 January 1841, Captain Elliot dispatched the Columbine to Chusan, with instructions to evacuate it for Hong Kong Island.[27][28] He declared the cession of Hong Kong to the United Kingdom after a tentative agreement with Chinese Imperial Commissioner Qishan a few days earlier.[29]

Notes

- The Chinese Repository, vol. 9, p. 408

- Mao 2016, p. 131

- Mao 2016, p. 132

- The Annual Register 1841, p. 573

- The Annual Register 1841, p. 576

- Jocelyn 1841, p. 49

- Ouchterlony 1841, p. vi

- Ouchterlony 1841, p. vii

- Jocelyn 1841, p. 51

- Jocelyn 1841, p. 52

- The Annual Register 1841, p. 577

- The Annual Register 1841, p. 574

- Jocelyn 1841, p. 55

- Mao 2016, pp. 133–134

- The Annual Register 1841, p. 578

- The Annual Register 1841, p. 575

- Ferguson, Brian (23 December 2017). "Treasures of the East go on show in Edinburgh". The Scotsman. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- Jocelyn 1841, p. 59

- Ouchterlony 1841, p. xii

- The Asiatic Journal, vol. 33, p. 351

- MacPherson 1843, pp. 21–22

- The Chinese Repository, vol. 10, p. 456

- Bernard & Hall 1845, p. 107

- The Annual Register 1842, p. 21

- Ouchterlony 1844, p. 54

- The Chinese Repository, vol. 10, pp. 452–453

- Ouchterlony 1844, p. 107

- Bingham 1843, p. 378

- The Chinese Repository, vol. 10, p. 63

References

- The Annual Register, or a View of the History, and Politics, of the Year 1840. London: J. G. F. & J. Rivington. 1841.

- The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British and Foreign India, China, and Australasia. Volume 33. London: Wm. H. Allen and Co. 1840.

- Bernard, W. D.; Hall, W. H. (1845). Narrative of the Voyages and Services of the Nemesis from 1840 to 1843 (2nd ed.). London: Henry Colburn.

- Bingham, John Elliot (1843). Narrative of the Expedition to China, from the Commencement of the War to Its Termination in 1842 (2nd ed.). Volume 1. London: Henry Colburn.

- The Chinese Repository. Volume 9. Canton. 1840.

- The Chinese Repository. Volume 10. Canton. 1841.

- "Chronicle: February". The Annual Register, or a View of the History, and Politics, of the Year 1841. London: J. G. F. & J. Rivington. 1842.

- Jocelyn, Robert (1841). Six Months with the Chinese Expedition; or, Leaves from a Soldier's Note-book (2nd ed.). London: John Murray.

- MacPherson, Duncan (1843). Two Years in China (2nd ed.). London: Saunders and Otley.

- Mao, Haijian (2016). The Qing Empire and the Opium War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-06987-9.

- Ouchterlony, John (1841). A Statistical Sketch of the Island of Chusan, with a Brief Note on the Geology of China. London: Pelham Richardson.

- Ouchterlony, John (1844). The Chinese War. London: Saunders and Otley.

External links