Conowingo Dam

The Conowingo Dam (also Conowingo Hydroelectric Plant, Conowingo Hydroelectric Station) is a large hydroelectric dam in the lower Susquehanna River near the town of Conowingo, Maryland. The medium-height, masonry gravity dam is one of the largest non-federal hydroelectric dams in the U.S.

| Conowingo Dam | |

|---|---|

Conowingo Dam, looking North | |

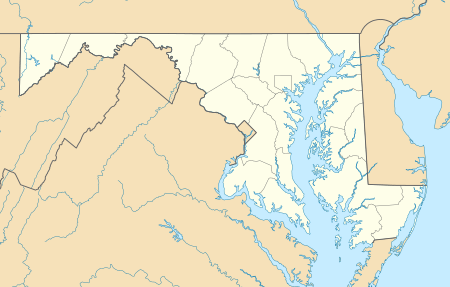

Location of Conowingo Dam in Maryland | |

| Official name | Conowingo Hydroelectric Station |

| Country | United States |

| Location | Cecil and Harford counties, Maryland |

| Coordinates | 39°39′36″N 76°10′26″W |

| Status | Operational |

| Construction began | 1926 (completed in 1928) |

| Opening date | 1928 |

| Owner(s) | Susquehanna Electric Company |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Type of dam | Gravity dam |

| Impounds | Susquehanna River |

| Height | 94 ft (29 m) |

| Length | 4,648 ft (1,417 m) |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | Conowingo Reservoir |

| Total capacity | 310,000 acre⋅ft (0.38 km3) |

| Active capacity | 71,000 acre⋅ft (0.088 km3) |

| Surface area | 9,000 acres (3,600 ha) |

| Maximum length | 4,648 ft (1,417 m) |

| Maximum water depth | 105 ft (32 m) |

| Normal elevation | 109.2 ft (33.3 m) |

| Power Station | |

| Operator(s) | Exelon |

| Commission date | 1928 |

| Type | Run-of-the-river |

| Turbines | 7 x 36 MWe, 4 x 65 MWe |

| Installed capacity | 548 MWe |

| Website Conowingo Hydroelectric Generating Station | |

The dam sits about 9.9 miles (16 km) from the river mouth at the Chesapeake Bay, 5 miles (8 km) south of the Pennsylvania border and 45 miles (72 km) northeast of Baltimore, on the border between Cecil and Harford counties.

The dam supports a 9,000-acre reservoir, which today covers the original town of Conowingo. During dam construction, the town was moved to its present location about 1-mile (1.6 km) northeast of the dam's eastern end. The rising water also would have covered Conowingo Bridge, the original U.S. Route 1 crossing, so it was demolished in 1927. U.S. Route 1 now crosses over the top of the dam.

The Conowingo Reservoir, and the nearby Susquehanna State Park, provide many recreational opportunities.

Construction and hydroelectric power generation

.jpg)

The area, which appears on a 1612 map by John Smith, was originally known as Smyth's Falls.

On January 23, 1925, Philadelphia Electric Company awarded the construction contract for the dam to Stone & Webster of Boston,[1] who did the design. Construction, which started in 1926, was carried out by Arundel Corporation of Maryland.[2] (Abandoned railroad tracks for transporting heavy equipment to the dam site can be seen along the western shore of the river below the dam.) When completed in 1928, it was the second-largest hydroelectric project by power output in the United States after Niagara Falls.[3]

Some 5,000 workers flocked to this rural northeastern corner of Maryland, seeking to earn good pay as construction got underway. In addition to those working directly on the dam, large numbers relocated railroad tracks, paved new roads, and constructed steel towers to stretch the mighty transmission lines toward Philadelphia. This was nearly fifty years before Congress passed the Occupational Safety and Health Act, which guaranteed the right to a safe job. While these men struggled to earn a living, many suffered disabling injuries handling high voltage electric lines, tumbling from high elevations, managing explosives, encountering poisonous snakes, and much more.

When Maryland Public Television aired its documentary, "Conowingo Dam: Power on the Susquehanna" for Chesapeake Bay Week in April 2016, the question came up about how many workers died performing their duties.[4] While investigating the death of Hunter H. Bettis on November 26, 1927, Darlington Coroner Wiliam B. Selse commented in the Baltimore Sun that more than twenty men had lost their lives. In an attempt to create a registry or census of job-related fatalities, death certificates, newspaper accounts, and funeral home books were examined. Fourteen individuals were identified.[5]

The dam was built with 11 turbine sites, although only seven turbines were initially installed, driving generators each rated for 36 megawatts. A turbine house, on the southwestern end of the dam, encloses these seven units. One additional "house" unit provides 25 Hz power for the dam's electric railroad system (identical to that used by the Pennsylvania Railroad, which had an electrified line [now under Norfolk Southern ownership] running on the eastern shore). In 1978, four higher-capacity turbines were added. Each drives a 65-megawatt generator, increasing the dam's electrical output capacity from 252 to 548 megawatts. The four newer turbines are in the open air section at the northeast end of the powerhouse. The generators produce power at 13,800 volts. This is stepped up to 220,000 volts for transmission, primarily to the Philadelphia area. The dam currently contributes an average of 1.6 billion kilowatt-hours annually to the electric grid.

Through subsidiaries and mergers, the dam is now operated by the Susquehanna Electric Company, part of Exelon Power Corporation. The current Federal Energy Regulatory Commission license for the dam was issued in 1980 and expired in 2014.[6]

The Conowingo Hydroelectric Station would be a primary black start power source if the regional PJM power grid ever had a widespread emergency shutdown (blackout).[7][8]

Flood control

The dam has 53 flood control gates, starting at the northeastern end of the powerhouse and spanning the majority of the dam. The flood gates are operated by three overhead cranes rated for 60 short tons (53.6 long tons; 54.4 t) each and built by the Morgan Engineering Company of Ohio. The cranes run on rails the length of the dam and are electrically powered from lines that run above the face of the dam. An additional crane was recently (c. 2006) installed at the power house end of the rails, which required installing new power rails below the existing power wires. As of 2017, all new overhead cranes have been installed with the original Morgan cranes removed and scrapped. The new cranes have backup generators installed on them to allow operation during a facility grid power failure.

In 1936, all the flood gates were opened for the first time. During Hurricane Agnes, in 1972, all 53 flood gates were opened, for only the second time, and explosives planted to blow a section of the weir, as the waters rose during the early morning hours of June 24 within 5 feet (1.52 m) of topping the dam (a record crest of 111.5 ft (34.0 m), 3 feet (0.91 m) above normal level for the entire 14-mile (23 km) long Conowingo Reservoir.) Paul English, dam superintendent, released a bulletin at 10:30 p.m. on June 23 saying that the water levels were reaching a point at which the stability of the dam "cannot be controlled. When it reaches 111 feet (33.8 m)...it will be in the hazy area...It is not known...whether a structure of the dam may give and...people downstream should be advised."[9] At this time, the flow sensor in the dam recorded its record discharge of 1,130,000 cu ft/s (32,000 m3/s), and the stream height gauge, at the dam's downstream side, registered a record 36.85 feet (11.23 m).[10] On January 20, 1996, the gauge recorded its second-highest recorded crest of 34.18 feet (10.42 m).[10] A severe ice jam also developed behind the dam on this date. The record minimum recorded discharge was on March 2, 1969, when the flow sensor registered 144 cu ft/s (4.1 m3/s).

On September 9, 2011, 44 flood gates were opened due to the impact of the remnants of Tropical Storm Lee. The Susquehanna River behind the dam was 32.41 feet (9.88 m), the third-highest in history. The town of Port Deposit, located 5 miles southeast of the dam, was evacuated.[11]

On July 26, 2018, 20 of the 53 floodgates were opened due to rising floodwaters resulting from several days of torrential downpours in the Mid-Atlantic. The Susquehanna saw water levels of over 26.25 feet (8.00 m), placing nearby cities, like Port Deposit, MD, at risk of flooding like in 2011.[12] The ecological impact of this event is not known, but Chesapeake Bay ecologists are concerned about the health of the Chesapeake Bay with the influx of sediment and limiting nutrients, such as phosphorus and nitrogen, impacting water clarity and promoting algal blooms.[13] The Coast Guard issued warnings for all vessels in the Chesapeake Bay regarding the fields of debris, floating and submerged, that had been released when the floodgates opened.

Ecology and environmental impacts

Conowingo Dam bridge | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°40′N 76°10′W |

| Carries | Two lanes of |

| ID number | 100000120001010 |

| Characteristics | |

| Width | 20 ft (6.1 m) |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 8850 (in 2002) |

| |

_in_northeastern_Harford_County%2C_Maryland%2C_approaching_the_southwest_end_of_the_Conowingo_Dam_on_the_Susquehanna_River.jpg)

The river water impounded by the dam forms the 14-mile (23 km) long Conowingo Reservoir, known locally as Conowingo Lake. The reservoir is used as a drinking water supply for Baltimore and the Chester Water Authority; as cooling water for the Peach Bottom Nuclear Generating Station; and for recreational boating and fishing. In low rainfall or drought conditions, balancing the desire to maintain the reservoir level with the water flow needs for the downstream ecology is one of the challenges faced by the dam operators.[14]

The Conowingo Dam, and to a lesser extent the Holtwood and Safe Harbor Dams further upstream, stopped migratory fish species, especially American shad, from swimming further up the Susquehanna River to spawn. In 1984, a fish capture feature was added at Conowingo and shad were trucked upstream above all three dams and released. This program ended in 1999. A fish lift was installed in 1991. All three dams completed installation of fish lifts in time for the 2000 season. During the 2000 migration season, 153,000 American shad passed through the Conowingo fish lift. "However, passage rates of shad from Conowingo to Holtwood have been only 30 to 50 percent, suggesting that fish are having difficulty moving upstream in the waters of the Conowingo pool."[15]

The three dams are also involved with another ecological concern. Normally, the reservoirs above each dam trap sediment and nutrients that run off from the watershed and prevent some of that from reaching the Chesapeake Bay. A 1998 USGS study suggests that they may reach capacity before 2020, and cease to reduce the nutrient and sediment load hitting the bay. However, the scouring of major floods, and other factors, affect this.[16]

References

- "PRR Chronology 1926 (citing New York Times)" (PDF).

- "History Matters! Interpretive Plan for the Lower Susquehanna Heritage Greenway" (PDF). p. 162. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2006. Retrieved July 15, 2006.

- "A Hydro Plant That Rivals Niagara." Popular Science Monthly, November 1930, p. 49.

- "Conowingo Dam: Power on the Susquehanna". Maryland Public Television. Maryland Public Television. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- "On Labor Day: Remembering Those Who Died While Building the Conowingo Dam". Window on Cecil County's Past. Window on Cecil County's Past. September 7, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- "Conowingo Dam » The Federal Licensing Process". Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- "Exelon Corporation: Conowingo". Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- "Conowingo Hydroelectric Project (FERC No. 405)". Low Impact Hydropower Institute. June 23, 2008. Archived from the original on May 10, 2008. Retrieved November 14, 2008.

- http://www.portdeposit.org/?a=history_detail and The Baltimore Sun, June 24, 1972

- "Historical Crests for Susquehanna River at Conowingo Dam". Archived from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2006.

- "Waiting is over for Maryland river towns, as Susquehanna waters recede". Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- "Hogan Administration Announces Statewide Response Efforts for Potential Conowingo Dam Impacts". Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- "Conowingo Dam High Flow Threatens Chesapeake Bay Pollution Goals, Ignites Tensions". Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- "CONOWINGO POOL MANAGEMENT PLAN" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2006. Retrieved July 22, 2006.

- "Migratory Fish Restoration and Passage On the Susquehanna River". Safe Harbor Water Power Corporation. Archived from the original on December 30, 2007. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- "USGS Fact Sheet 003-98". 1998. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- Safe Harbor Water Power Corporation, Conestoga, PA. "How Fish Lifts Work."

External links

- U.S. Geological Survey. Conowingo Dam real-time water flow data

- Thinkquest (Oracle Education Foundation). "Conowingo Hydroelectric Plant." - Virtual tour with interior pictures and diagrams

- National Weather Service. NWS Flood Stage Info. for Susquehanna River at Conowingo

- Maryland Public Television. Promo Video: Conowingo Dam: Power on the Susquehanna An introduction to the MPT one-hour documentary

- "Promo Video: Conowingo Dam: Power on the Susquehanna". Maryland Public TV. Maryland Public Television. Retrieved February 4, 2019.