Concubinage

Concubinage (/kənˈkjuːbɪnɪdʒ/ kəng-KYOO-bih-nij) is an interpersonal and sexual relationship between a man and a woman in which the couple are not or cannot be married.[1] The inability to marry may be due to multiple factors such as differences in social rank status, an existing marriage, religious or professional prohibitions, or a lack of recognition by appropriate authorities. The woman in such a relationship is referred to as a concubine (/ˈkɒŋkjʊˌbaɪn/ KONG-kyoo-bine). A concubine among polygynyous peoples is a secondary wife, usually of inferior rank.[2][3][4]

Relationships (Outline) |

|---|

|

Endings |

Concubines have existed in all cultures, though the prevalence of concubinage and the status of rights and expectations of a concubine have varied somewhat, as have the rights of children of a concubine. Whatever the status and rights of the concubine, they were always inferior to those of the wife, and typically neither she nor her children had rights of inheritance. Especially among royalty and nobility, the woman in such relationships was commonly described as a mistress. The children of such relationships were counted as illegitimate and in some societies were barred from inheriting the father's title or estates, even in the absence of legitimate heirs.

In Asia

Concubinage was highly popular before the early 20th century all over East Asia. The main function of concubinage was producing additional heirs, as well as bringing males pleasure. Children of concubines had lower rights in account to inheritance, which was regulated by the Dishu system.

Mongols

Polygyny and concubinage were very common in Mongol society especially for powerful Mongol men. Genghis Khan, Ögedei Khan, Jochi, Tolui, and Kublai Khan (among others) all had many wives and concubines.

Genghis Khan frequently acquired wives and concubines from empires and societies that he had conquered, these women were often princesses or queens that were taken captive or gifted to him.[5] Genghis Khan's most famous concubine was Möge Khatun, according to the Persian historian Ata-Malik Juvayni she was "given to Chinggis Khan by a chief of the Bakrin tribe, and he loved her very much."[6] After Genghis Khan died, Möge Khatun became a wife of Ögedei Khan. Ögedei also favored her as a wife, and she frequently accompanied him on his hunting expeditions.[7]

China

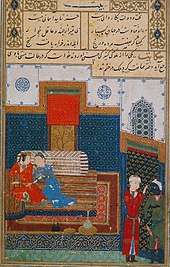

In China, successful men often had concubines until the practice was outlawed when the Chinese Communist Party came to power in 1949. The standard Chinese term translated as "concubine" was qiè 妾, a term that has been used since ancient times, which means "concubine; I, your servant (deprecating self reference)". Concubinage resembled marriage in that concubines were recognized sexual partners of a man and were expected to bear children for him. Unofficial concubines (Chinese: 婢妾; pinyin: bì qiè) were of lower status, and their children were considered illegitimate. The English term concubine is also used for what the Chinese refer to as pínfēi (Chinese: 嬪妃), or "consorts of emperors", an official position often carrying a very high rank.[8]

In premodern China it was illegal and socially disreputable for a man to have more than one wife at a time, but it was acceptable to have concubines.[9] In the earliest records a man could have as many concubines as he could afford. From the Eastern Han period (AD 25–220) onward, the number of concubines a man could have was limited by law. The higher rank and the more noble identity a man possessed, the more concubines he was permitted to have.[10]

A concubine's treatment and situation was variable and was influenced by the social status of the male to whom she was attached, as well as the attitude of his wife. In the Book of Rites chapter on "The Pattern of the Family" (Chinese: 內則) it says, “If there were betrothal rites, she became a wife; and if she went without these, a concubine.”[11] Wives brought a dowry to a relationship, but concubines did not. A concubinage relationship could be entered into without the ceremonies used in marriages, and neither remarriage nor a return to her natal home in widowhood were allowed to a concubine.[12]

The position of the concubine was generally inferior to that of the wife. Although a concubine could produce heirs, her children would be inferior in social status to a wife's children, although they were of higher status than illegitimate children. The child of a concubine had to show filial duty to two women, their biological mother and their legal mother—the wife of their father.[13] After the death of a concubine, her sons would make an offering to her, but these offerings were not continued by the concubine's grandsons, who only made offerings to their grandfather's wife.[14]

There are early records of concubines allegedly being buried alive with their masters to "keep them company in the afterlife".[15] Until the Song dynasty (960–1276), it was considered a serious breach of social ethics to promote a concubine to a wife.[12]

During the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), the status of concubines improved. It became permissible to promote a concubine to wife, if the original wife had died and the concubine was the mother of the only surviving sons. Moreover, the prohibition against forcing a widow to remarry was extended to widowed concubines. During this period tablets for concubine-mothers seem to have been more commonly placed in family ancestral altars, and genealogies of some lineages listed concubine-mothers.[12]

Imperial concubines, kept by emperors in the Forbidden City, had different ranks and were traditionally guarded by eunuchs to ensure that they could not be impregnated by anyone but the emperor.[15] In Ming China (1368–1644) there was an official system to select concubines for the emperor. The age of the candidates ranged mainly from 14 to 16. Virtues, behavior, character, appearance and body condition were the selection criteria.[16]

Despite the limitations imposed on Chinese concubines, there are several examples in history and literature of concubines who achieved great power and influence. Lady Yehenara, otherwise known as Empress Dowager Cixi, was arguably one of the most successful concubines in Chinese history. Cixi first entered the court as a concubine to Xianfeng Emperor and gave birth to his only surviving son, who later became Tongzhi Emperor. She eventually became the de facto ruler of Qing China for 47 years after her husband's death.[17]

An examination of concubinage features in one of the Four Great Classical Novels, Dream of the Red Chamber (believed to be a semi-autobiographical account of author Cao Xueqin's family life). Three generations of the Jia family are supported by one notable concubine of the emperor, Jia Yuanchun, the full elder sister of the male protagonist Jia Baoyu. In contrast, their younger half-siblings by concubine Zhao, Jia Tanchun and Jia Huan, develop distorted personalities because they are the children of a concubine.

Emperors' concubines and harems are emphasized in 21st-century romantic novels written for female readers and set in ancient times. As a plot element, the children of concubines are depicted with a status much inferior to that in actual history. The zhai dou (Chinese: 宅斗,residential intrigue) and gong dou (Chinese: 宫斗,harem intrigue) genres show concubines and wives, as well as their children, scheming secretly to gain power. Empresses in the Palace, a gong dou type novel and TV drama, has had great success in 21st-century China.[18]

Hong Kong and Macau

Hong Kong officially abolished the Great Qing Legal Code in 1971, thereby making concubinage illegal. Casino magnate Stanley Ho of Macau took his "second wife" as his official concubine in 1957, while his "third and fourth wives" retain no official status.[19]

Japan

Before monogamy was legally imposed in the Meiji period, concubinage was common among the nobility.[20] Its purpose was to ensure male heirs. For example, the son of an Imperial concubine often had a chance of becoming emperor. Yanagihara Naruko, a high-ranking concubine of Emperor Meiji, gave birth to Emperor Taishō, who was later legally adopted by Empress Haruko, Emperor Meiji's formal wife. Even among merchant families, concubinage was occasionally used to ensure heirs. Asako Hirooka, an entrepreneur who was the daughter of a concubine, worked hard to help her husband's family survive after the Meiji Restoration. She lost her fertility giving birth to her only daughter, Kameko; so her husband—with whom she got along well—took Asako's maid-servant as a concubine and fathered three daughters and a son with her. Kameko, as the child of the formal wife, married a noble man and matrilineally carried on the family name.[21]

A Samurai could take concubines but their backgrounds were checked by higher-ranked samurai. In many cases, taking a concubine was akin to a marriage. Kidnapping a concubine, although common in fiction, would have been shameful, if not criminal. If the concubine was a commoner, a messenger was sent with betrothal money or a note for exemption of tax to ask for her parents' acceptance. Even though the woman would not be a legal wife, a situation normally considered a demotion, many wealthy merchants believed that being the concubine of a samurai was superior to being the legal wife of a commoner. When a merchant's daughter married a samurai, her family's money erased the samurai's debts, and the samurai's social status improved the standing of the merchant family. If a samurai's commoner concubine gave birth to a son, the son could inherit his father's social status.

Concubines sometimes wielded significant influence. Nene, wife of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, was known to overrule her husband's decisions at times and Yodo-dono, his concubine, became the de facto master of Osaka castle and the Toyotomi clan after Hideyoshi's death.

Korea

Joseon monarchs had a harem which contained concubines of different ranks. Empress Myeongseong managed to have sons, preventing sons of concubines getting power.

Children of concubines often had lower value in account of marriage. A daughter of concubine could not marry a wife-born son of the same class. For example, Jang Nok-su was a concubine-born daughter of a mayor, who was initially married to a slave-servant, and later became a high-ranking concubine of Yeonsangun.

Vikings

Polygyny was common among Vikings, rich and powerful Viking men tended to have many wives and concubines. Viking men would often buy or capture women and make them into their wives or concubines.[22][23] Researchers have suggested that Vikings may have originally started sailing and raiding due to a need to seek out women from foreign lands.[24][25][26][27] Polygynous relationships in Viking society may have led to a shortage of eligible women for the average male, this is because polygyny increases male-male competition in society because it creates a pool of unmarried men who are willing to engage in risky status-elevating and sex seeking behaviors.[28][29] Due to this, the average Viking man could have been forced to perform riskier actions to gain wealth and power to be able to find suitable women.[30][31][32] The concept was expressed in the 11th century by historian Dudo of Saint-Quentin in his semi imaginary History of The Normans.[33] The Annals of Ulster depicts raptio and states that in 821 the Vikings plundered an Irish village and "carried off a great number of women into captivity".[34]

Ancient Egypt

While most Ancient Egyptians were monogamous, a male pharaoh would have had other, lesser wives and concubines in addition to the Great Royal Wife. This arrangement would allow the pharaoh to enter into diplomatic marriages with the daughters of allies, as was the custom of ancient kings.[35] Concubinage was a common occupation for women in ancient Egypt, especially for talented women. A request for forty concubines by Amenhotep III (c. 1386-1353 BCE) to a man named Milkilu, Prince of Gezer states:

"Behold, I have sent you Hanya, the commissioner of the archers, with merchandise in order to have beautiful concubines, i.e. weavers. Silver, gold, garments, all sort of precious stones, chairs of ebony, as well as all good things, worth 160 deben. In total: forty concubines - the price of every concubine is forty of silver. Therefore, send very beautiful concubines without blemish." - (Lewis, 146)[36]

Concubines would be kept in the pharaoh's harem. Amenhotep III kept his concubines in his palace at Malkata, which was one of the most opulent in the history of Egypt. The king was considered to be deserving of many women as long as he cared for his Great Royal Wife as well.[36]

Greco-Roman Antiquity

Ancient Greece

In Ancient Greece the practice of keeping a concubine (Ancient Greek: παλλακίς pallakís) was common among the upper classes, and they were for the most part women who were slaves or foreigners, but occasional free born based on family arrangements (typically from poor families).[37] Children produced by slaves remained slaves and those by non-slave concubines varied over time; sometimes they had the possibility of citizenship.[38] The law prescribed that a man could kill another man caught attempting a relationship with his concubine.[39] By the mid 4th century concubines could inherit property, but, like wives, they were treated as sexual property.[40] While references to the sexual exploitation of maidservants appear in literature, it was considered disgraceful for a man to keep such women under the same roof as his wife.[41] Apollodorus of Acharnae said that hetaera were concubines when they had a permanent relationship with a single man, but nonetheless used the two terms interchangably.[42]

Ancient Rome

Concubinage was an institution practiced in ancient Rome that allowed a man to enter into an informal but recognized relationship with a woman (concubina, plural concubinae) who was not his wife, most often a woman whose lower social status was an obstacle to marriage. Concubinage was "tolerated to the degree that it did not threaten the religious and legal integrity of the family".[43] It was not considered derogatory to be called a concubina, as the title was often inscribed on tombstones.[44]

In Abrahamic religions

In Judaism

In Judaism, a concubine is a marital companion of inferior status to a wife.[45] Among the Israelites, men commonly acknowledged their concubines, and such women enjoyed the same rights in the house as legitimate wives.[46]

In ancient Judaism

The term concubine did not necessarily refer to women after the first wife. A man could have many wives and concubines. Legally, any children born to a concubine were considered to be the children of the wife she was under. Sarah had to get Ishmael out of her house because legally Ishmael would always be the first born son even though Isaac was her natural child. The concubine may not have commanded the exact amount of respect as the wife. In the Levitical rules on sexual relations, the Hebrew word that is commonly translated as "wife" is distinct from the Hebrew word that means "concubine". However, on at least one other occasion the term is used to refer to a woman who is not a wife – specifically, the handmaiden of Jacob's wife.[47] In the Levitical code, sexual intercourse between a man and a wife of a different man was forbidden and punishable by death for both persons involved.[48][49] Since it was regarded as the highest blessing to have many children, wives often gave their maids to their husbands if they were barren, as in the cases of Sarah and Hagar, and Rachel and Bilhah. The children of the concubine often had equal rights with those of the wife;[46] for example, King Abimelech was the son of Gideon and his concubine.[50] Later biblical figures such as Gideon, and Solomon had concubines in addition to many childbearing wives. For example, the Books of Kings say that Solomon had 700 wives and 300 concubines.[51]

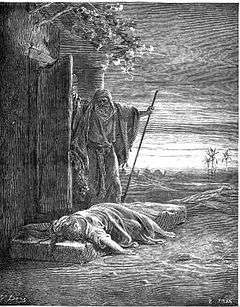

The account of the unnamed Levite in Judges 19–20[52] shows that the taking of concubines was not the exclusive preserve of kings or patriarchs in Israel during the time of the Judges, and that the rape of a concubine was completely unacceptable to the Israelite nation and led to a civil war. In the story, the Levite appears to be an ordinary member of the tribe, whose concubine was a woman from Bethlehem in Judah. This woman was unfaithful, and eventually abandoned him to return to her paternal household. However, after four months, the Levite, referred to as her husband, decided to travel to her father's house to persuade his concubine to return. She is amenable to returning with him, and the father-in-law is very welcoming. The father-in-law convinces the Levite to remain several additional days, until the party leaves behind schedule in the late evening. The group pass up a nearby non-Israelite town to arrive very late in the city of Gibeah, which is in the land of the Benjaminites. The group sit around the town square, waiting for a local to invite them in for the evening, as was the custom for travelers. A local old man invites them to stay in his home, offering them guest right by washing their feet and offering them food. A band of wicked townsmen attack the house and demand the host send out the Levite man so they can have sex with him. The host offers to send out his virgin daughter as well as the Levite's concubine for them to rape, to avoid breaking guest right towards the Levite. Eventually, to ensure his own safety and that of his host, the Levite gives the men his concubine, who is raped and abused through the night, until she is left collapsed against the front door at dawn. In the morning, the Levite finds her when he tries to leave. When she fails to respond to her husband's order to get up, most likely because she is dead, the Levite places her on his donkey and continues home. Once home, he dismembers her body and distributes the 12 parts throughout the nation of Israel. The Israelites gather to learn why they were sent such grisly gifts, and are told by the Levite of the sadistic rape of his concubine. The crime is considered outrageous by the Israelite tribesmen, who then wreak total retribution on the men of Gibeah, as well as the surrounding tribe of Benjamin when they support the Gibeans, killing them without mercy and burning all their towns. The inhabitants of (the town of) Jabesh Gilead are then slaughtered as a punishment for not joining the eleven tribes in their war against the Benjaminites, and their four hundred unmarried daughters given in forced marriage to the six hundred Benjamite survivors. Finally, the two hundred Benjaminite survivors who still have no wives are granted a mass marriage by abduction by the other tribes.

In modern Judaism

In Judaism, concubines are referred to by the Hebrew term pilegesh (Hebrew: פילגש). The term is a loanword from Ancient Greek παλλακίς,[53][54][55] meaning "a mistress staying in house".

According to the Babylonian Talmud,[46] the difference between a concubine and a legitimate wife was that the latter received a ketubah and her marriage (nissu'in) was preceded by an erusin ("formal betrothal"), which was not the case for a concubine.[56] One opinion in the Jerusalem Talmud argues that the concubine should also receive a marriage contract, but without a clause specifying a divorce settlement.[46] According to Rashi, "wives with kiddushin and ketubbah, concubines with kiddushin but without ketubbah"; this reading is from the Jerusalem Talmud,[45]

Certain Jewish thinkers, such as Maimonides, believed that concubines were strictly reserved for royal leadership and thus that a commoner may not have a concubine. Indeed, such thinkers argued that commoners may not engage in any type of sexual relations outside of a marriage.

Maimonides was not the first Jewish thinker to criticise concubinage. For example, Leviticus Rabbah severely condemns the custom.[57] Other Jewish thinkers, such as Nahmanides, Samuel ben Uri Shraga Phoebus, and Jacob Emden, strongly objected to the idea that concubines should be forbidden.

In the Hebrew of the contemporary State of Israel, pilegesh is often used as the equivalent of the English word "mistress"—i.e., the female partner in extramarital relations—regardless of legal recognition. Attempts have been initiated to popularise pilegesh as a form of premarital, non-marital or extramarital relationship (which, according to the perspective of the enacting person(s), is permitted by Jewish law).[58][59][60]

In Islam and the Arab world

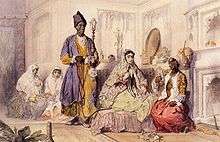

Concubinage according to Islamic sexual jurisprudence is not permitted because any sex before marriage is prohibited. Muslim scholars vehemently reject concubinage all along,[61][62][63] which was not considered prostitution, and was very common during the Arab slave trade throughout the Middle Ages and early modern period, when women and girls from the Caucasus, Africa, Central Asia and Europe were captured and served as concubines in the harems of the Arab World.[64] Ibn Battuta tells us several times that he was given or purchased female slaves.[65]

Concubinage is permitted and regulated in Islam. Al-Muminun 6 and Al-Maarij 30 both, in identical wording, draw a distinction between spouses and "those whom one's right hands possess" (concubines), saying " أَزْوَاجِهِمْ أَوْ مَا مَلَكَتْ أَيْمَانُهُمْ" (literally, "their spouses or what their right hands possess"), while clarifying that sexual intercourse with either is permissible. However both these surahs literal wording[66][67] do not specifically use the term wife but instead the more general & both-gender including term spouse in the grammatically masculine plural (azwajihim), thus Mohammad Asad in his commentary to both these Surahs rules out concubinage due to the fact that "since the term azwaj ("spouses"), too, denotes both the male and the female partners in marriage, there is no reason for attributing to the phrase aw ma malakat aymanuhum the meaning of "their female slaves"; and since, on the other hand, it is out of the question that female and male slaves could have been referred to here, it is obvious that this phrase does not relate to slaves at all, but has the same meaning as in 4:24 namely, "those whom they rightfully possess through wedlock" with the significant difference that in the present context this expression relates to both husbands and wives, who "rightfully possess" one another by virtue of marriage."[68] Following this approach, Mohammad Asads translation of the mentioned verses denotes a different picture, which is as follows: "with any but their spouses - that is, those whom they rightfully possess [through wedlock]".[69] Sayyid Abul Ala Maududi explains that "two categories of women have been excluded from the general command of guarding the private parts: (a) wives, (b) women who are legally in one's possession".[70] "Concubine" (surriyya) refers to the female slave (jāriya), whether Muslim or non-Muslim, with whom her master engages in sexual intercourse. The word "surriyya" is not mentioned in the Qur'an. However, the expression "Ma malakat aymanukum" (that which your right hands own), which occurs fifteen times in the sacred book, refers to slaves and therefore, though not necessarily, to concubines. Concubinage was a pre-Islamic custom that was allowed to be practiced under Islam with Jews and non-Muslim people to marry concubine after teaching her and instructing her well and then giving them freedom.[71] Rationale given for recognition of concubinage in Islam is that "it satisfied the sexual desire of the female slaves and thereby prevented the spread of immorality in the Muslim community."[72] Most schools restrict concubinage to a relationship where the female slave is required to be monogamous to her master[73] (though the master's monogamy to her is not required), but according to Sikainga, "in reality, however, female slaves in many Muslim societies were prey for [male] members of their owners' household, their [owner's male] neighbors, and their [owner's male] guests."[72] Concubines were common in pre-Islamic Arabia and when Islam arrived, it had a society with concubines. Islam introduced legal restrictions to the concubinage[74] and encouraged manumission.[75] Islam furthermore endorsed educating, freeing and marrying female slaves.[76] In verse 23:6 in the Quran it is allowed to have sexual intercourse with concubines after marrying them, as Islam forbids sexual intercourse outside of marriage.[77] Children of former concubines were generally declared as legitimate with or without wedlock, and the mother of a free child was considered free upon the death of the male partner.

According to Shia Muslims, Muhammad sanctioned Nikah mut‘ah (fixed-term marriage, called muta'a in Iraq and sigheh in Iran) which has instead been used as a legitimizing cover for sex workers, in a culture where prostitution is otherwise forbidden.[78] Some Western writers have argued that mut'ah approximates prostitution.[79] Julie Parshall writes that mut'ah is legalised prostitution which has been sanctioned by the Twelver Shia authorities. She quotes the Oxford encyclopedia of modern Islamic world to differentiate between marriage (nikah) and Mut'ah, and states that while nikah is for procreation, mut'ah is just for sexual gratification.[80] According to Zeyno Baran, this kind of temporary marriage provides Shi'ite men with a religiously sanctioned equivalent to prostitution.[81] According to Elena Andreeva's observation published in 2007, Russian travellers to Iran consider mut'ah to be "legalized profligacy" which is indistinguishable from prostitution.[82] Religious supporters of mut'ah argue that temporary marriage is different from prostitution for a couple of reasons, including the necessity of iddah in case the couple have sexual intercourse. It means that if a woman marries a man in this way and has sex, she has to wait for a number of months before marrying again and therefore, a woman cannot marry more than 3 or 4 times in a year.[83][84][85][86][87]

Pre-modern times

In ancient times, two sources for concubines were permitted under an Islamic regime. Primarily, non-Muslim women taken as prisoners of war were made concubines as happened after the Battle of the Trench,[88] or in numerous later Caliphates.[89] It was encouraged to manumit slave women who rejected their initial faith and embraced Islam, or to bring them into formal marriage.

Modern times

According to the rules of Islamic Fiqh, what is halal (permitted) by Allah in the Quran cannot be altered by any authority or individual.

It is further clarified that all domestic and organizational female employees are not concubines in this era and hence sex is forbidden with them unless Nikah,[90] Nikah mut‘ah[91] or Nikah Misyar is committed through the proper channels.

In the United States

When slavery became institutionalized in the North American colonies, white men, whether or not they were married, sometimes took enslaved women as concubines; children of such unions remained slaves.[92] Marriage between the races was prohibited by law in the colonies and the later United States. Many colonies and states also had laws against miscegenation, or any interracial relations. From 1662 the Colony of Virginia, followed by others, incorporated into law the principle that children took their mother's status, i.e., the principle of partus sequitur ventrem.[93] This led to generations of multiracial slaves, some of whom were otherwise considered legally white (one-eighth or less African, equivalent to a great-grandparent) before the American Civil War.

In some cases, men had long-term relationships with enslaved women, giving them and their mixed-race children freedom and providing their children with apprenticeships, education and transfer of capital. A relationship between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings is an example of this.[94] Such arrangements were more prevalent in the Southern states during the antebellum years.

Plaçage

In Louisiana and former French territories, a formalized system of concubinage called plaçage developed. European men took enslaved or free women of color as mistresses after making arrangements to give them a dowry, house or other transfer of property, and sometimes, if they were enslaved, offering freedom and education for their children.[95] A third class of free people of color developed, especially in New Orleans.[95][96] Many became educated, artisans and property owners. French-speaking and practicing Catholicism, these women combined French and African-American culture and created an elite between those of European descent and the slaves.[95] Today, descendants of the free people of color are generally called Louisiana Creole people.[95]

See also

References

- Bonnie G. Smith (2008). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. Oxford University Press. pp. 467–. ISBN 978-0-19-514890-9.

- "Dictionary.com - Concubine". Dictionary. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- "Definition of CONCUBINE". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "CONCUBINE | definition in the Cambridge English Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- Broadbridge, Anne F. (18 July 2018). Women and the Making of the Mongol Empire. Cambridge University Press. pp. 74, 92. ISBN 978-1-108-63662-9.

- McClynn, Frank (14 July 2015). Genghis Khan: His Conquests, His Empire, His Legacy. Hachette Books. p. 117. ISBN 978-0306823961.

- De Nicola, Bruno (2017). Women in Mongol Iran: The Khatuns, 1206-1335. Edinburgh University Press. p. 68.

- Patricia Buckley Ebrey (2002): Women and the Family in Chinese History. Oxford: Routledge, p. 39.

- Ebrey 2002:39.

- Shi Fengyi 史凤仪 (1987): Zhongguo gudai hunyin yu jiating 中国古代婚姻与家庭 Marriage and Family in Ancient China. Wuhan: Hubei Renmin Chubanshe, p. 74.

- Nei Ze. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- Ebrey 2002: 60.

- Ebrey 2002: 54.

- Ebrey 2002: 42.

- "Concubines of Ancient China". Beijing Made Easy. Beijing Made Easy. 2012. Archived from the original on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- Qiu Zhonglin(Chung-lin Ch'iu)邱仲麟:"Mingdai linxuan Houfei jiqi guizhi" 明代遴選後妃及其規制 (The Imperial Concubine Selection System during the Ming Dynasty). Mingdai Yanjiu 明代研究 (Ming Studies) 11.2008:58.

- Sterling Seagrave, Peggy Seagrave (1993). Dragon lady: the life and legend of the last empress of China. Vintage Books.

- "Top 10 Chinese entertainment events in 2012 (7) - People's Daily Online". en.people.cn. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- "港台剧怀旧经典". www.aiweibang.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- "Concubinage in Asia". Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- INC., SANKEI DIGITAL. "【九転十起の女(27)】女盛りもとうに過ぎ…夫とお手伝いの間に子供". Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- Karras, Ruth Mazo (1990). "Concubinage and Slavery in the Viking Age". Scandinavian Studies. 62 (2): 141–162. ISSN 0036-5637. JSTOR 40919117.

- Poser, Charles M. (1994). "The dissemination of multiple sclerosis: A Viking saga? A historical essay". Annals of Neurology. 36 (S2): S231–S243. doi:10.1002/ana.410360810. ISSN 1531-8249. PMID 7998792.

- Hrala, Josh. "Vikings Might Have Started Raiding Because There Was a Shortage of Single Women". ScienceAlert. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- Choi, Charles Q.; November 8, Live Science Contributor |; ET, 2016 09:07am. "The Real Reason for Viking Raids: Shortage of Eligible Women?". Live Science. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- "Sex Slaves – The Dirty Secret Behind The Founding Of Iceland". All That's Interesting. 16 January 2018. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- "Kinder, Gentler Vikings? Not According to Their Slaves". National Geographic News. 28 December 2015. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- Raffield, Ben; Price, Neil; Collard, Mark (1 May 2017). "Male-biased operational sex ratios and the Viking phenomenon: an evolutionary anthropological perspective on Late Iron Age Scandinavian raiding". Evolution and Human Behavior. 38 (3): 315–24. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.10.013. ISSN 1090-5138.

- LawlerApr. 15, rew; 2016; Am, 3:00 (13 April 2016). "Vikings may have first taken to seas to find women, slaves". Science | AAAS. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Viegas, Jennifer (17 September 2008). "Viking Age triggered by shortage of wives?". msnbc.com. Archived from the original on 23 July 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- Knapton, Sarah (5 November 2016). "Viking raiders were only trying to win their future wives' hearts". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- "New Viking Study Points to "Love and Marriage" as the Main Reason for their Raids". The Vintage News. 22 October 2018. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- David R. Wyatt (2009). Slaves and Warriors in Medieval Britain and Ireland: 800–1200. Brill. p. 124. ISBN 978-90-04-17533-4.

- Andrea Dolfini; Rachel J. Crellin; Christian Horn; Marion Uckelmann (2018). Prehistoric Warfare and Violence: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. Springer. p. 349. ISBN 978-3-319-78828-9.

- Shaw, Garry J. The Pharaoh, Life at Court and on Campaign, Thames and Hudson, 2012, p. 48, 91-94.

- "Women in Ancient Egypt". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- Sue Blundell; Susan Blundell (1995). Women in Ancient Greece. Harvard University Press. pp. 124–. ISBN 978-0-674-95473-1.

- Nigel Guy Wilson (2006). Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece. Psychology Press. pp. 158–. ISBN 978-0-415-97334-2.

- James Davidson (1998). Courtesans and Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens. p. 98. ISBN 0-312-18559-6.

- Bonnie MacLachlan (31 May 2012). Women in Ancient Greece: A Sourcebook. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 74–. ISBN 978-1-4411-0964-4.

- James Davidson (1998). Courtesans and Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens. pp. 98–99. ISBN 0-312-18559-6.

- James Davidson (1998). Courtesans and Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens. p. 101. ISBN 0-312-18559-6.

- Grimal, Love in Ancient Rome (University of Oklahoma Press) 1986:111.

- Kiefer, Sexual Life in Ancient Rome (Kegan Paul International) 2000:50.

- "Concubine". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- Staff (2002–2011). "PILEGESH (Hebrew, ; comp. Greek, παλλακίς).". Jewish Encyclopedia. JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- Genesis 30:4

- Leviticus 20:10

- Deuteronomy 22:22

- Judges 8:31

- 1 Kings 11:1–3

- Judges 19, Judges 20

- Michael Lieb, Milton and the culture of violence, p.274, Cornell University Press, 1994

- Agendas for the study of Midrash in the twenty-first century, Marc Lee Raphael, p.136, Dept. of Religion, College of William and Mary, 1999

- Nicholas Clapp, Sheba: Through the Desert in Search of the Legendary Queen, p.297, Houghton Mifflin, 2002

- "PILEGESH (Hebrew, ; comp. Greek, παλλακίς)". Jewish Virtual Library.

- Leviticus Rabbah, 25

- Matthew Wagner (16 March 2006). "Kosher sex without marriage". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 3 May 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- Adam Dickter, "ISO: Kosher Concubine", New York Jewish Week, December 2006

- Suzanne Glass, "The Concubine Connection" Archived 3 January 2013 at Archive.today, The Independent, London 20 October 1996

- Asad, Mohammad. The Message of the Quran. pp. Surah 4:25 [commentary].

This passage lays down in an unequivocal manner that sexual relations with female slaves are permitted only on the basis of marriage, and that in this respect there is no difference between them and free women; consequently, concubinage is ruled out.“

- Quran, translated by Mustafa Islamoğlu. pp. Surah 23:6, Commentary.

- Mohammad Asad: The Message of the Quran, Surah 23:6, [Commentary].

Lit., "or those whom their right hands possess" (aw ma malakat aymanuhum). Most of the commentators assume unquestioningly that this relates to female slaves, and that the particle aw ("or") denotes a permissible alternative. This conventional interpretation is, in my opinion inadmissible inasmuch as it is based on the assumption that sexual intercourse with one's female slave is permitted without marriage: an assumption which is contradicted by the Qur'an itself (see 4:3, {24}, {25} and 24:32, with the corresponding notes). Nor is this the only objection to the above-mentioned interpretation. Since the Qur'an applies the term "believers" to men and women alike, and since the term azwaj ("spouses"), too, denotes both the male and the female partners in marriage, there is no reason for attributing to the phrase aw ma malakat aymanuhum the meaning of "their female slaves"; and since, on the other hand, it is out of the question that female and male slaves could have been referred to here, it is obvious that this phrase does not relate to slaves at all, but has the same meaning as in 4:24- namely, "those whom they rightfully possess through wedlock" (see note [26] on 4:24) - with the significant difference that in the present context this expression relates to both husbands and wives, who "rightfully possess" one another by virtue of marriage. On the basis of this interpretation, the particle aw which precedes this clause does not denote an alternative ("or") but is, rather, in the nature of an explanatory amplification, more or less analgous to the phrase "in other words" or "that is", thus giving to the whole sentence the meaning, "...save with their spouses - that is, those whom they rightfully possess [through wedlock]...", etc. (Cf. a similar construction 25:62 - "for him who has the will to take thought - that is [lit., "or"], has the will to be grateful".)“

- "BBC – Religions – Islam: Slavery in Islam". Archived from the original on 21 May 2009. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- Insights into the concept of Slavery Archived 2009-11-22 at the Wayback Machine. San Francisco Unified School District.

- "Surah Marijj 30".

- "Surah Muminun 6".

- Asad, Mohammad. The Message of the Quran. pp. Surah Muminun, Ayah 6 (See note 3).

- Asad, Muhammad. Ibid. pp. Surah Muminun ayah 6.

- "Surah – AL – MUMINOON". 11 March 2007. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007.

- "Al-Adab Al-Mufrad / Book-9 / Hadith-48". quranx.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- Sikainga, Ahmad A. (1996). Slaves Into Workers: Emancipation and Labor in Colonial Sudan. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-77694-2. p.22

- Bloom, Jonathan; Blair, Sheila (2002). Islam: A Thousand Years of Faith and Power. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09422-1. p.48

- "Maarif ul Quran". Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- "Surah Al-Baqara 2:177-177 – Maariful Quran – Maarif ul Quran – Quran Translation and Commentary". Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- Sahih Bukhari Volume 3, Book 46, Number 724.

The Prophet said, "He who has a slave-girl and teaches her good manners and improves her education and then manumits and marries her, will get a double reward.

- "A Study of the Quran – 3. Does the Qur'an permit sex outside marriage with female slaves?". Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- İlkkaracan, Pınar (2008). Deconstructing sexuality in the Middle East: challenges and discourses. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-7546-7235-7.

- İlkkaracan, Pınar (2008). Deconstructing sexuality in the Middle East: challenges and discourses. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-7546-7235-7. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015.

- Parshall, Philip L.; Parshall, Julie (1 April 2003). Lifting the Veil: The World of Muslim Women. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 9780830856961.

- Baran, Zeyno (21 July 2011). Citizen Islam: The Future of Muslim Integration in the West. A&C Black. ISBN 9781441112484.

- Andreeva, Elena (2007). Russia and Iran in the great game: travelogues and Orientalism. Routledge studies in Middle Eastern history. 8. Psychology Press. pp. 162–163. ISBN 0415771536. "Most of the travelers describe the Shi'i institution of temporary marriage (sigheh) as 'legalized profligacy' and hardly distinguish between temporary marriage and prostitution."

- Temporary Marriage in Islam Part 6: Similarities and Differences of Mut’a and Regular Marriage | A Shi'ite Encyclopedia | Books on Islam and Muslims | Al-Islam.org..

- "Marriage » Mut'ah (temporary marriage) – Islamic Laws – The Official Website of the Office of His Eminence Al-Sayyid Ali Al-Husseini Al-Sistani". www.sistani.org. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- "The Rules in Matrimony and Marriage". Al-Islam.org. 3 October 2012. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- "How is Mutah different from prostitution (from a non-Muslim point of view)?". islam.stackexchange.com. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- "Marriage". english.bayynat.org.lb. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- Majlisi, M. B. (1966). Hayat-ul-Qaloob, Volume 2, Translated by Molvi Syed Basharat Hussain Sahib Kamil, Imamia Kutub Khana, Lahore, Pakistan

- Murat Iyigun, “Lessons From the Ottoman Harem on Culture, Religion & Wars”, University of Colorado, 2011

- "Definition of Nikah (Islamic marriage)". nikah.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2004. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- Motahhari M. "The rights of woman in Islam, fixed-term marriage and the problem of the harem" Archived 28 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Al-islam.org website. Accessed 15 March 2014.

- Amott, Teresa L.; Matthaei, Julie A. (1996). Race, Gender, and Work: A Multi-cultural Economic History of Women in the United States. South End Press. ISBN 9780896085374.

- Peter Kolchin, American Slavery, 1619–1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1993, p. 17

- "Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: A Brief Account" Archived 30 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Monticello Website, Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved 22 June 2011. Quote: "Ten years later [referring to its 2000 report], TJF and most historians now believe that, years after his wife's death, Thomas Jefferson was the father of the six children of Sally Hemings mentioned in Jefferson's records, including Beverly, Harriet, Madison and Eston Hemings ... Since then, a committee commissioned by the Thomas Jefferson Heritage Society, after reviewing essentially the same material, reached different conclusions, namely that Sally Hemings was only a minor figure in Thomas Jefferson's life and that it is very unlikely he fathered any of her children. This committee also suggested in its report, issued in April 2001 and revised in 2011, that Jefferson's younger brother Randolph (1755–1815) was more likely the father of at least some of Sally Hemings's children."

- Helen Bush Caver and Mary T. Williams, "Creoles" Archived 13 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Multicultural America, Countries and Their Cultures Website. Retrieved 3 Feb 2009

- Peter Kolchin, American Slavery, 1619–1865, New York: Hill and Wang, 1993, pp. 82–83

External links

| Look up concubinage or concubine in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Servile Concubinage