Classless society

Classless society refers to a society in which no one is born into a social class. Such distinctions of wealth, income, education, culture, or social network might arise and would only be determined by individual experience and achievement in such a society. For the opposite see class society.

Helen Codere defines social class as a segment of the community, the members of which show a common social position in a hierarchical ranking.[1] Codere suggest that a true class-organized society is one in which the hierarchy of prestige and status is divisible into groups each with its own social, economic, attitudinal and cultural characteristics and each having differential degrees of power in community decision.[1]

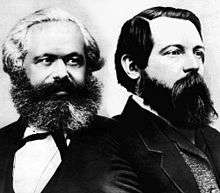

Since determination of life outcome by birth class has proved historically difficult to avoid, advocates of a classless society such as anarchists, communists and libertarian socialists propose various means to achieve and maintain it and attach varying degrees of importance to it as an end in their overall programs/philosophy.

Classlessness

The term classlessness has been used to describe different social phenomena.

In societies where classes have been abolished, it is usually the result of a voluntary decision by the membership to form such a society to abolish a pre-existing class structure in an existing society or to form a new one without any. This would include communes of the modern period such as various American utopian communities or the kibbutzim as well as revolutionary and political acts at the nation-state level such as the Paris Commune or the Russian Revolution. The abolition of social classes and the establishment of a classless society is the primary goal of anarchism, communism and libertarian socialism.

Classlessness also refers to the state of mind required in order to operate effectively as a social anthropologist. Anthropological training includes making assessments of and therefore becoming aware of one's own class assumptions so that these can be set aside from conclusions reached about other societies. This may be compared to ethnocentric biases or the "neutral axiology" required by Max Weber. Otherwise conclusions reached about studied societies will likely be coloured by the anthropologist's own class values.

Classlessness can also refer to a society that has acquired pervasive and substantial social justice where the economic upper class wields no special political power and poverty as experienced historically is virtually nonexistent as it cannot be achieved.

According to Ulrich Beck, classlessness is achieved with class struggle: "It is the collective success with class struggle which institutionalizes individualization and dissolves the culture of classes, even under conditions of radicalizing inequalities".[2] Essentially, classlessness will exist when the inequalities and injustice out ranks societies idea of the need for social ranking and hierarchy.

Social classes in present day

The state of social classes in society today is disputed. If the actual development is taken by the discussion, then Western society has moved past classes to a classless society. This is reinforced by the statement from Becker and Andreas Hadjar: "The weakening of class identities is also postulated by Savage (2000, p. 37), who assumes that although individuals may still refer to social class, class position no longer generates a deep sense of identity and belonging".[3] Some say that society today has not completely abolished classes, but that distinctions can be only attributed to experience and success (meritocracy). Others maintain that the class system remains in place, e.g. by showing that children's success in education correlates with their parent's wealth, and wealth being inherited.[4]

Marxist definition

In Marxist theory, tribal hunter-gatherer society, primitive communism, was classless. Everyone was equal in a basic sense as a member of the tribe and the different functional assignments of the primitive mode of production, howsoever rigid and stratified they might be, did not and could not simply because of the numbers produce a class society as such. With the transition to agriculture, the possibility to make a surplus product, i.e. to produce more than what is necessary to satisfy one's immediate needs, developed in the course of development of the productive forces. According to Marxism, this also made it possible for a class society to develop because the surplus product could be used to nourish a ruling class which did not participate in production.

Libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism, also called left-libertarianism, social anarchism, social libertarianism and socialist libertarianism, is a group of anti-authoritarian socialist political philosophies that rejects socialism as the centralised state ownership and control of the economy, which they regard as state capitalism. Political philosophy is the study of fundamental questions about the government, state, justice, politics, liberty and the enforcement of a legal code by an authoritative body. According to Charles Larmore, the second approach sees political philosophy as the freedom to discipline one-self from the basic features of the human condition that make up the reality of political life.[5]

Libertarianism is a collection of political philosophies and movements that uphold liberty as a core principle.[6] Libertarians seek to maximize political freedom and autonomy, emphasizing freedom of choice, voluntary association and individual judgment.[7][8][9] Libertarians share a skepticism of authority and state power, but they diverge on the scope of their opposition to existing political and economic systems. Various schools of libertarian thought offer a range of views regarding the legitimate functions of state and private power, often calling for the restriction or dissolution of coercive social institutions.[10]

Past and present political philosophies and movements commonly described as libertarian socialist include anarchism (especially anarcho-communism, anarcho-syndicalism,[11] collectivist anarchism and mutualism)[12] as well as autonomism, communalism, participism, guild socialism,[13] revolutionary syndicalism and libertarian Marxist[14] philosophies such as council communism[15] and Luxemburgism[16] as well as some versions of utopian socialism[17] and individualist anarchism.[18][19][20][21]

See also

- Bourgeoisie

- Communist revolution

- Corporate power

- Equality of outcome

- False consciousness

- Middle class

- New class

- Proletariat

- Social class in Colombia

- Social class in France

- Social class in Italy

- Social class in New Zealand

- Social class in the United States

- Social equality

- Social organization

- Social status

- Socialism

- Stateless communism

- Working class

References

- Codere, H. (1957). Kwakiutl Society: Rank without Class. American Anthropologist, 59(3), 473–486. JSTOR 665913

- Beck, U. (2007). Beyond class and nation: Reframing social inequalities in a globalizing world. The British Journal of Sociology, 58(4), 679-705. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00171.x

- Becker, R. and Hadjar, A. (2013), “Individualisation” and class structure: how individual lives are still affected by social inequalities. International Social Science Journal, 64: 211–223. doi:10.1111/issj.12044

- Of course class still matters – it influences everything that we do, Will Hutton, The Guardian, January 10, 2010

- Larmore, C. (2013). What is political philosophy? Journal of Moral Philosophy, 10 (3), 276-306. doi:10.1163/174552412X628896

- Boaz, David, David Boaz (January 30, 2009). "Libertarianism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

...libertarianism, political philosophy that takes individual liberty to be the primary political value.

- Woodcock, George (2004). Anarchism: A History Of Libertarian Ideas And Movements. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781551116297.

for the very nature of the libertarian attitude—its rejection of dogma, its deliberate avoidance of rigidly systematic theory, and, above all, its stress on extreme freedom of choice and on the primacy of the individual judgment

- Boaz, David (1999). "Key Concepts of Libertarianism". Cato Institute. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- "What Is Libertarian?". Institute for Humane Studies. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- Long, Joseph.W (1996). "Toward a Libertarian Theory of Class." Social Philosophy and Policy. 15:2 p. 310. "When I speak of 'libertarianism'... I mean all three of these very different movements. It might be protested that LibCap ["libertarian capitalism"], LibSoc ["libertarian socialism"] and LibPop ["libertarian populism] are too different from one another to be treated as aspects of a single point of view. But they do share a common—or at least an overlapping—intellectual ancestry."

- Sims, Franwa (2006). The Anacostia Diaries As It Is. Lulu Press. p. 160.

- A Mutualist FAQ: A.4. Are Mutualists Socialists? Archived 2009-06-09 at the Wayback Machine

- "It is by meeting such a twofold requirement that the libertarian socialism of G.D.H. Cole could be said to offer timely and sustainable avenues for the institutionalization of the liberal value of autonomy..." Charles Masquelier. Critical theory and libertarian socialism: Realizing the political potential of critical social theory. Bloombury. New York-London. 2014. pg. 190.

- "Locating libertarian socialism in a grey area between anarchist and Marxist extremes, they argue that the multiple experiences of historical convergence remain inspirational and that, through these examples, the hope of socialist transformation survives." Alex Prichard, Ruth Kinna, Saku Pinta and Dave Berry (eds) Libertarian Socialism: Politics in Black and Red. Palgrave Macmillan, December 2012. pg. 13.

- "Councilism and anarchism loosely merged into ‘libertarian socialism’, offering a non-dogmatic path by which both council communism and anarchism could be updated for the changed conditions of the time, and for the new forms of proletarian resistance to these new conditions." Toby Boraman. "Carnival and Class: Anarchism and Councilism in Australasia during the 1970s" in Alex Prichard, Ruth Kinna, Saku Pinta and Dave Berry (eds). Libertarian Socialism: Politics in Black and Red. Palgrave Macmillan, December 2012. pg. 268.

- Murray Bookchin, Ghost of Anarcho-Syndicalism; Robert Graham, The General Idea of Proudhon's Revolution.

- Kent Bromley, in his preface to Peter Kropotkin's book The Conquest of Bread, considered early French utopian socialist Charles Fourier to be the founder of the libertarian branch of socialist thought, as opposed to the authoritarian socialist ideas of Babeuf and Buonarroti." Kropotkin, Peter. The Conquest of Bread, preface by Kent Bromley, New York and London, G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1906.

- "(Benjamin) Tucker referred to himself many times as a socialist and considered his philosophy to be "Anarchistic socialism." An Anarchist FAQ by Various Authors

- French individualist anarchist Émile Armand shows clearly opposition to capitalism and centralized economies when he said that the individualist anarchist "inwardly he remains refractory – fatally refractory – morally, intellectually, economically (The capitalist economy and the directed economy, the speculators and the fabricators of single are equally repugnant to him.)""Anarchist Individualism as a Life and Activity" by Emile Armand

- Anarchist Peter Sabatini reports that in the United States "of early to mid-19th century, there appeared an array of communal and "utopian" counterculture groups (including the so-called free love movement). William Godwin's anarchism exerted an ideological influence on some of this, but more so the socialism of Robert Owen and Charles Fourier. After success of his British venture, Owen himself established a cooperative community within the United States at New Harmony, Indiana during 1825. One member of this commune was Josiah Warren (1798–1874), considered to be the first individualist anarchist". Peter Sabatini. "Libertarianism: Bogus Anarchy"

- "It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism." Chartier, Gary; Johnson, Charles W. (2011). Markets Not Capitalism: Individualist Anarchism Against Bosses, Inequality, Corporate Power, and Structural Poverty. Brooklyn, NY: Minor Compositions/Autonomedia. Pg. Back cover.

- Anarchism (2015). In The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather Guide. Abington, United Kingdom: Helicon.

- Beitzinger, A. J.; Bromberg, H. (2013). Anarchism. In Fastiggi, R. L. (ed.). New Catholic Encyclopedia Supplement 2012-2013. Detroit: Gale. Vol. 1. pp. 70–72.