Diadectes

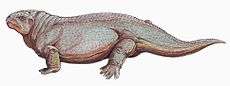

Diadectes (meaning crosswise-biter) is an extinct genus of large, very reptile-like amphibians that lived during the early Permian period (Artinskian-Kungurian stages of the Cisuralian epoch, between 290 and 272 million years ago).[1] Diadectes was one of the first herbivorous tetrapods, and also one of the first fully terrestrial animals to attain large size.

| Diadectes | |

|---|---|

| Mounted skeleton of D. sideropelicus, American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Diadectomorpha |

| Family: | †Diadectidae |

| Genus: | †Diadectes Cope, 1878 |

| Type species | |

| †Diadectes sideropelicus Cope, 1878 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

Silvadectes | |

Description

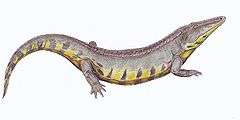

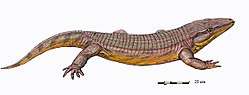

Diadectes was a heavily built animal, 1.5 to 3 m (5 to 10 ft) long, with a thick-boned skull, heavy vertebrae and ribs, massive limb girdles, and short, robust limbs. The nature of the limbs and vertebrae clearly indicates a terrestrial animal. The rib cage was assumed to be barrel-shaped, but new fossils show the ribs were actually sticking out to the sides.[2]

Paleobiology

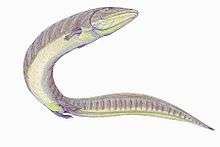

It possesses some characteristics of reptilians and amphibians, combining a reptile-like skeleton with a more primitive, seymouriamorph-like skull. Diadectes has been classified as belonging to the sister group of the amniotes.

Among its primitive features, Diadectes has a large otic notch (a feature found in all labyrinthodonts, but not in reptiles) with an ossified tympanum. At the same time, its teeth show advanced specialisations for an herbivorous diet that are not found in any other type of early Permian animal. The eight front teeth are spatulate and peg-like, and served as incisors that were used to nip off mouthfuls of vegetation. The broad, blunt cheek teeth show extensive wear associated with occlusion, and would have functioned as molars, grinding up the food. It also had a partial secondary palate, which meant it could chew its food and breathe at the same time, something many even more advanced reptiles were unable to do.

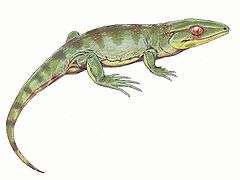

These traits are likely adaptations related to the animals' high-fiber, herbivorous diet, and evolved independently of similar traits seen in some reptilian groups. Many of the reptile-like details of the postcranial skeleton are possibly related to carrying the substantial trunk; these may be independently derived traits on Diadectes and their relatives. Though very similar, they would be analogous rather than homologous to those of early amniotes such as pelycosaurs and pareiasaurs, as the first reptiles evolved from small, swamp-dwelling animals like Casineria and Westlothiana.[3][4] The phenomenon of unrelated animals evolving similarly is known as convergent evolution.[5]

Discovery

Diadectes was first named and described by American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope in 1878,[6] based on part of a lower jaw (AMNH 4360) from the Permian of Texas. Cope noted: "Teeth with short and much compressed crowns, whose long axis is transverse to that of the jaws," the feature expressed in the generic name Diadectes "crosswise biter" (from Greek dia "crosswise" + Greek dēktēs "biter"). He described the animal as "in all probability, herbivorous." Cope's neo-Latin type species name sideropelicus (from Greek sidēros "iron" + Greek pēlos "clay" + -ikos) "of iron clay" alluded to the Wichita beds in Texas, where the fossil was found. Diadectes fossil remains are known from a number of locations across North America, especially the Texas Red Beds (Wichita and Clear Fork).

Classification and species

Numerous species have been assigned to Diadectes, though most of those have proven to be synonyms of one another. Similarly, many supposed separate genera of diadectids have been shown to be junior synonyms of Diadectes. One of these, Nothodon, was actually published by Othniel Charles Marsh five days before the name Diadectes was published by his rival Cope. Despite this fact, in 1912, Case synonymized the two names and treated Diadectes as the senior synonym, which has been followed by other paleontologists since, despite the fact that it violates the rules of International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN).[1]

Phylogeny

A phylogenetic analysis of Diadectes and related diadectids was presented in an unpublished PhD thesis by Richard Kissel in 2010. Previous phylogenetic analyses of diadectids had found D. absitus to be more basal than other species of Diadectes, outside the derived clade composed of these species. In these analyses, Diasparactus zenos was more closely related to the other species of Diadectes than was D. absitus, making Diadectes paraphyletic. Kissel recovered this paraphyly in his analysis and proposed the new genus name "Silvadectes" for D. absitus.[7] Below is the cladogram from Kissel's thesis:

| Diadectomorpha |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

However, according to the ICZN, a name presented in an initially unpublished thesis such as Kissel's is not valid. Because the name "Silvadectes" has not yet been formally erected in a published paper, it was not, as of 2010, considered valid.

References

- Kissel, R. (2010). "Morphology, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha)." Thesis (Graduate Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology University of Toronto).

- Dig into new bones in Seymour - Newschannel 6 Now | Wichita Falls, TX

- Carroll R.L. (1991): The origin of reptiles. In: Schultze H.-P., Trueb L., (ed) Origins of the higher groups of tetrapods — controversy and consensus. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp 331-353.

- Laurin, M. (2004): The Evolution of Body Size, Cope's Rule and the Origin of Amniotes. Systematic Biology no 53 (4): pp 594-622. doi:10.1080/10635150490445706 article

- Mayr, Ernst, and Peter D. Ashlock (1991): Principles of systematic zoology. New York: McGraw-Hill

- Cope, E.D. (1878). "Descriptions of extinct Batrachia and Reptilia from the Permian formation of Texas". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 17: 505–530.

- Kissel, R. (2010). Morphology, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 185. hdl:1807/24357.

- Parker, Steve. Dinosaurus: the complete guide to dinosaurs. Firefly Books Inc, 2003. Pg. 83

- Benton, M. J. (2000), Vertebrate Paleontology, 2nd ed. Blackwell Science Ltd

- Carroll, R. L. (1988), Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution, WH Freeman & Co.

- Colbert, E. H., (1969), Evolution of the Vertebrates, John Wiley & Sons Inc (2nd ed.)

- Reisz, Robert, (no date), Biology 356 - Major Features of Vertebrate Evolution - Anthracosaurs and Diadectomorphs