Neopteroplax

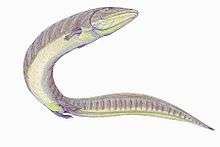

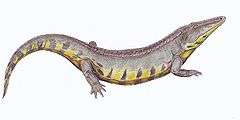

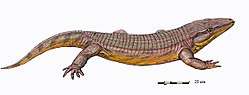

Neopteroplax is an extinct genus of eogyrinid embolomere closely related to European genera such as Eogyrinus and Pteroplax.[1] Members of this genus were among the largest embolomeres (and Carboniferous tetrapods in general) in North America. Neopteroplax is primarily known from a large (~40 cm) skull found in Ohio, although fragmentary embolomere fossils from Texas and New Mexico[2] have also been tentatively referred to the genus. Despite its similarities to specific European embolomeres, it can be distinguished from them due to a small number of skull and jaw features, most notably a lower surangular at the upper rear portion of the lower jaw.[1]

| Neopteroplax | |

|---|---|

_(Birmingham_Shale%2C_Upper_Pennsylvanian%3B_Bloomingdale%2C_Ohio%2C_USA)_1_(49761151626).jpg) | |

| Skull cast of N. conemaughensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Embolomeri |

| Family: | †Eogyrinidae |

| Genus: | †Neopteroplax Romer, 1963 |

| Type species | |

| Neopteroplax conemaughensis Romer, 1963 | |

| Other species | |

| |

Discovery

The type species, Neopteroplax conemaughensis, is known from a large skull found in Late Carboniferous shale during railroad renovations in Bloomingdale, Ohio. Although damaged by excavators, most of the left side of the skull can be reconstructed based on surviving fragments. The only other Neopteroplax fossils recovered from this site were a few rib and vertebra fragments. The site was geologically slightly younger than the famous Carboniferous deposits of the nearby Linton diamond coal mine. Other fossils found near the Neopteroplax skull include fragments of fin spines from Edaphosaurus and several small amphibians (including a Platyhystrix-like form), as well as teeth from early chondrichthyan fish like Cladodus, petalodonts, and cochliodonts. The skull was described, reconstructed and named by Alfred Sherwood Romer in 1963, as part of a study on various new Carboniferous embolomere fossils from Eastern North America. Citing similarities to certain European embolomeres (often referred to the genera Pteroplax or Eogyrinus), he named the skull Neopteroplax conemaughensis, in reference to both Pteroplax as well as the geological formation which the skull was found in (the Conemaugh series of Ohio).[1]

Jaw fragments and vertebrae similar to those of N. conemaughensis have also been recovered from the Thrifty Formation of Texas, which lies close to the border between the Carboniferous and Permian periods. These Texan remains were assigned to the second species of Neopteroplax, Neopteroplax relictus. These two species are mainly differentiated by their geographical and temporal isolation.[1] Large embolomerous vertebrae and jaws from the Wild Cow Formation of New Mexico have also been tentatively assigned to Neopteroplax by Lucas et al. (1999).[2] Some sources, such as Marjanovic & Laurin (2019), have doubted the validity of these western remains' referral to the genus.[3]

Description

Counting the enlarged cheek regions, the skull was 39.5 centimeters (15.6 inches) in length. The snout was moderately long and the skull as a whole was deep, although crushing has reduced this depth and splayed out the cheeks, making the fossil wider than it would have been when alive. The overall shape and texture was similar to that of most other embolomeres, although there is no trace of lateral line canals. Sutures between skull bones are difficult to interpret with certainty, but when visible, their arrangement and structure is similar to that of other embolomeres (particularly English specimens commonly referred to Pteroplax or Eogyrinus). For example, the lacrimal bone is excluded from the front edge of the orbit (eye socket) due to a downward branch of the prefrontal bone, and the broad squamosal bone is only weakly attached to skull bones above it.[1] The orbits were roughly circular, in contrast with a well-preserved embolomere skull from Newsham (initially referred to Anthracosaurus and now considered the lectotype of Eogyrinus), which has more triangular orbits due to the shape of the jugal bone, which forms the lower rim of the orbit.[4] On the other hand, the jugal of Neopteroplax otherwise resembles that of the Newsham skull due to extending down far enough that it wraps under the rim of the mouth. The premaxilla (at the tip of the snout) had three teeth, with the first two rather large and the last one much smaller. The following maxilla bone had about 40 teeth, which were generally small except for a "canine" region of four or five larger teeth near the front part of the bone. All of the teeth were only preserved as broken stumps at best, so specific information about their shape is unobtainable.[1]

The front part of the palate (roof of the mouth) has large, elliptical choanae (internal nostrils) separated by narrow, toothless vomer bones. Most of the palate was formed by the plate-like pterygoid bones, which were covered with tiny denticles. The outer edge of each pterygoid connected to a small, rectangular palatine bone and the longer ectopterygoid, which lies immediately behind it. The palatine and ectopterygoid possessed very large fangs, with two on the palatine and six on the ectopterygoid. Very little of the braincase is well preserved, with the exception of the blade-like parasphenoid which extends forwards along the midline of the skull and divides most of the pterygoids from each other.[1]

The lower jaw of Neopteroplax possessed typical embolomere features such as two large meckelian fenestra (holes visible on the inner surface of the jaw), but it also has a few unique and diagnostic traits. It was approximately 34.2 cm (13.5 in) long, deep towards the rear and tapering and curving upwards towards the front. However, the rear portion of the jaw is not as deep as in the European embolomeres. This is because the surangular bone, which forms the upper portion of the jaw behind the tooth row, was only gently convex along its upper edge, rather than strongly arched with a pronounced crest. The outer surface of the jaw has an pronounced lateral line canal which becomes more indistinct towards the jaw joint. Like the rest of the skull, tooth preservation on the jaw is too poor to conclude much about its dentition. However, it is clear that the first of the coronoids (a series of bones adjacent and inwards of the main tooth row) was toothless, in contrast to Eobaphetes and Eogyrinus, which have denticles on the first coronoid.[1][4]

References

- Romer, Alfred S. (February 1963). "The larger embolomerous amphibians of the American Carboniferous". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 128: 415–454.

- Lucas, Spencer G.; Rowland, J. Mark; Kues, Barry S.; Estep, John W.; Wilde, Garner L. (1999). "Uppermost Pennsylvanian and Permian stratigraphy and biostratigraphy at Placitas, New Mexico" (PDF). Albuquerque Geology.

- Marjanović, David; Laurin, Michel (2019-01-04). "Phylogeny of Paleozoic limbed vertebrates reassessed through revision and expansion of the largest published relevant data matrix". PeerJ. 6: e5565. doi:10.7717/peerj.5565. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 6322490. PMID 30631641.

- Panchen, A. L. (10 February 1972). "The skull and skeleton of Eogyrinus attheyi Watson (Amphibia: Labyrinthodontia)". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 263 (851): 279–326. doi:10.1098/rstb.1972.0002. ISSN 0080-4622.