Germain of Paris

Germain (Latin: Germanus; c. 496 – 28 May 576) was the bishop of Paris and is a saint of the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church. According to an early biography, he was known as Germain d'Autun, rendered in modern times as the "Father of the Poor".[1]

Saint Germain of Paris | |

|---|---|

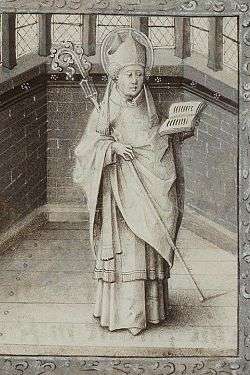

Saint Germain of Paris from a Book of Hours illuminated by Jean le Tavernier, c. 1450–1460. | |

| Bishop of Paris, Father of the Poor | |

| Born | c. 496 near Autun, Kingdom of the Burgundians (now France) |

| Died | 28 May 576 (aged 79-80) Paris, Kingdom of the Franks (now France) |

| Feast | 28 May |

Biography

Germain was born near Autun in what is now France, under Burgundian control 20 years after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, to noble Gallo-Roman parents.[2] Germain studied at Avallon in Burgundy and at Luzy under the guidance of his cousin Scallion, who was a priest. At the age of 35, he was ordained by Agrippinus of Autun and became abbot of the nearby Abbey of St. Symphorian. He was known for his hardworking and austere nature; however, it was his generous alms-giving which caused his monks to fear that one day he would give away all the wealth of the abbey, resulting in their rebellion against him. While in Paris in 555, Sibelius, the bishop of Paris, died, and King Childebert had him consecrated as the bishop of Paris.[3]

Under Germain's influence, Childebert is said to have led a reformed life. In his new role, the bishop continued to practice the virtues and austerities of his monastic life, working to diminish the suffering caused by the incessant wars. He attended the Third and Fourth Councils of Paris (557, 573) and also the Second Council of Tours (566). He persuaded the king to stamp out the pagan practices existing in Gaul and to forbid the excess that accompanied the celebration of most Christian festivals.[3]

Childebert was succeeded briefly by Clotaire, who divided the royal demesnes among his four sons, with Charibert becoming King of Paris. Germain was forced to excommunicate Charibert in 568 for immorality. Charibert died in 570. As his surviving brothers fought violently over his possessions, the bishop encountered great difficulty trying to establish peace, with little success. Sigebert and Chilperic, instigated by their wives, Brunehaut and the infamous Fredegund, went to war. Chilperic was defeated, and Paris fell into Sigebert's hands. Germain later wrote to Brunehaut, asking her to use her influence to prevent further war. However, Sigebert refused and, despite Germain's warning, set out to attack Chilperic at Tournai. Chilperic had fled, and Sigebert was later assassinated at Vitry in 575, under Fredegund's orders.[3] Germain died the following year, before peace was restored.

For nine centuries, in times of plague and crisis, his relics were carried in procession through the streets of Paris.[4]

Two stained-glass panels depicting scenes from the life of Germain are in Metropolitan Museum of Art's Cloisters Collection.[5]

Abbey church of Saint-Germain-des-Prés

During his war on Spain in the year 542, King Childebert besieged Zaragoza. Upon hearing that the inhabitants had placed themselves under the protection of the martyr Vincent of Saragossa, Childebert raised his siege and spared the city. In gratitude, the bishop of Zaragoza presented him with Germain's stole. When Childebert returned to Paris, he caused a church to be erected to receive the relic. In 558 St. Vincent's church was completed and dedicated by Germain on 23 December; on the very same day, Childebert died. A monastery was erected near the church. Its abbots had both spiritual and temporal jurisdiction over the suburbs of Saint-Germain until about the year 1670. The church was frequently plundered and set on fire by the Normans in the ninth century. It was rebuilt in 1014 and dedicated in 1163 by Pope Alexander III.[3]

There is a treatise on the ancient Gallican liturgy that has traditionally been attributed to Germain. The poet Venantius Fortunatus, from whom Germain commissioned a Vita Sancti Marcelli,[6] wrote a eulogy of his life.

Germain's body lay for two centuries in a tomb chamber in the chapel of Saint Symphorian, in the atrium or forecourt of the church of Saint Vincent outside the walls of Paris. The translation of his relics to a more prominent and typically Frankish position within the main church, retro altare, was effected in 756 and was justified by his vision to a pious woman.[7] The church was reconsecrated as Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Fortunatus had visited Germain in Paris and was disappointed so described the work as "nothing but a string of miracles".[8] Germain, according to Venantius had performed his first miracle in the womb, preventing his mother from performing an abortion.[9]

Germain's feast day is appointed as 28 May,[3] and his translation as 25 July.[10]

References

- Jones, Terry. "Germanus of Paris". Patron Saints Index. Archived from the original on 31 December 2006. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- The quality of noble birth as a requisite for episcopacy in works of Covenants Fortunate is discussed by Simon Coates, "Venantius Fortunatus and the image of episcopal authority in Late Antique and early Merovingian Gaul" The English Historical Review 115 (November 2000:1109–1137) esp. pp. 1115ff.

- MacErlean, Andrew. "St. Germain." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 27 October 2017

- Virginia Wylie Egbert, "The Reliquary of Saint Germain" The Burlington Magazine 112 (June 1970:359–65).

- Hayward, Jane. English and French medieval stained glass in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Vol. 1, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003, ISBN 9781872501376

- Simon Coates, "Venantius Fortunatus and the Image of Episcopal Authority in Late Antique and Early Merovingian Gaul" The English Historical Review 115 (November 2000:1109–1137) p. 1113.

- Warner Jacobson, "Saints' Tombs in Frankish Church Architecture" Speculate 72.4 (October 1997:1107–1143) p. 1133 and note 66.

- E. W. Brooks, reviewing the volume of Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Passiones Vitaeque Sanctorum Aevi Merovingici, B. Krusch and W. Levison, eds. (1919) that contains Fortunatus' vita, in The English Historical Review, 35 No. 139 (July 1920:438–440).

- Singled out by Coates 2000:1116.

- The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford, 2013), p. 228.

External links