Chandelas of Jejakabhukti

The Chandelas of Jejakabhukti were a royal dynasty in Central India. They ruled much of the Bundelkhand region (then called Jejakabhukti) between the 9th and the 13th centuries.

Chandelas of Jejakabhukti | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9th century CE–13th century CE | |||||||||

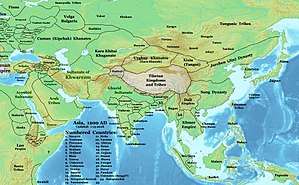

Map of Asia in 1200 CE. Chandela kingdom is shown in central India. | |||||||||

| Capital | Khajuraho Kalanjara Mahoba | ||||||||

| Common languages | Sanskrit | ||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism Jainism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

• c. 831 – c. 845 CE | Nannuka | ||||||||

• c. 1003 – c. 1035 CE | Vidyadhara | ||||||||

• c. 1288 – c. 1311 CE | Hammiravarman | ||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval India | ||||||||

• Established | 9th century CE | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 13th century CE | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||||

| Outline of South Asian history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Palaeolithic (2,500,000–250,000 BC) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Neolithic (10,800–3300 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chalcolithic (3500–1500 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bronze Age (3300–1300 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Iron Age (1500–200 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Middle Kingdoms (230 BC – AD 1206) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late medieval period (1206–1526)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern period (1526–1858)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Colonial states (1510–1961)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Periods of Sri Lanka

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Specialised histories |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Chandelas initially ruled as feudatories of the Gurjara-Pratiharas of Kanyakubja (Kannauj). The 10th century Chandela ruler Yashovarman became practically independent, although he continued to acknowledge the Pratihara suzerainty. By the time of his successor Dhanga, the Chandelas had become a sovereign power. Their power rose and declined as they fought battles with the neighbouring dynasties, especially the Paramaras of Malwa and the Kalachuris of Tripuri. From the 11th century onwards, the Chandelas faced raids by the northern Muslim dynasties, including the Ghaznavids and the Ghurids. The Chandela power effectively ended around the beginning of the 13th century, following Chahamana and Ghurid invasions.

The Chandelas are well known for their art and architecture, most notably for the temples at their original capital Khajuraho. They also commissioned a number of temples, water bodies, palaces and forts at other places, including their strongholds of Ajaigarh, Kalinjar and their later capital Mahoba.

Origin

The origin of the Chandelas is obscured by mythical legends. The epigraphic records of the dynasty, as well as contemporary texts such as Balabhadra-vilasa and Prabodha-chandrodaya, suggest that the Chandelas belonged to the legendary Lunar dynasty (Chandravansha).[1] A 954 CE Khajuraho inscription states that the dynasty's first king Nannuka was a descendant of sage Chandratreya, who was a son of Atri. A 1002 CE Khajuraho inscription gives a slightly different account, in which Chandratreya is mentioned as a son of Indu (the Moon) and a grandson of Atri.[2] The 1195 CE Baghari inscription and the 1260 CE Ajaygadh inscription contain similar mythical accounts.[3] The Balabhadra-vilasa also names Atri among the ancestors of the Chandelas. Another Khajuraho inscription describes the Chandela king Dhanga as a member of the Vrishni clan of the Yadavas (who also claimed to be part of the Lunar dynasty).[1]

The later medieval texts include Chandelas among the 36 Rajput clans. These include Mahoba-Khanda, Varna Ratnakara, Prithviraj Raso and Kumarapala-charita. The Mahoba-Khanda legend of the dynasty's origin goes like this: Hemaraja, a priest of the Gaharwar king of Benares, had a beautiful daughter named Hemavati. Once, while Hemavati was bathing in a pond, the moon god Chandra saw her and made love to her. Hemavati was worried about the dishonour of being an unwed mother, but Chandra assured her that their son would become a great king. This child was the dynasty's progenitor Chandravarma. Chandra presented him with a philosopher's stone and taught him politics.[4][1] The dynasty's own records do not mention Hemavati, Hemaraja or Indrajit. Such legends appear to be later bardic inventions. In general, the Mahoba-Khanda is a historically unreliable text.[2]

British indologist V. A. Smith theorized that the Chandelas were of either Bhar or Gond origin. Some other scholars including R. C. Majumdar also supported this theory.[5] The Chandelas worshipped Maniya, a tribal goddess, whose temples are located at Mahoba and Maniyagadh.[6] Besides, they have been associated with places that are also associated with Bhars and Gonds. Also, Rani Durgavati, whose family claimed Chandela descent married a Gond chief of Garha-Mandla.[7] Historian R. K. Dikshit does not find these arguments convincing: he argues that Maniya was not a tribal deity.[8] Also, the dynasty's association with Gond territory is not necessarily indicative of a common descent: the dynasty's progenitor may have been posted as a governor in these territories.[7] Finally, Durgavati's marriage to a Gond chief can be dismissed as a one-off case.[8]

History

Early rulers

The Chandelas were originally vassals of the Gurjara-Pratiharas.[9] Nannuka (r. c. 831-845 CE), the founder of the dynasty, was the ruler of a small kingdom centered around Khajuraho.[10]

According to the Chandela inscriptions, Nannuka's successor Vakpati defeated several enemies.[11] Vakpati's sons Jayashakti (Jeja) and Vijayashakti (Vija) consolidated the Chandela power.[12] According to a Mahoba inscription, the Chandela territory was named "Jejakabhukti" after the Jayashakti.[13] Vijayashakti's successor Rahila is credited with several military victories in eulogistic inscriptions.[14] Rahila's son Harsha played an important role in restoring the rule of the Pratihara king Mahipala, possibly after a Rashtrakuta invasion or after Mahiapala's conflict with his step-brother Bhoja II.[15]

Rise as a sovereign power

Harsha's son Yashovarman (r. c. 925-950 CE) continued to acknowledge the Pratihara suzerainty, but became practically independent.[16] He conquered the important fortress of Kalanjara.[17] A 953-954 CE Khajuraho inscription credits him with several other military successes, including against Gaudas (identified with the Palas), the Khasas, the Chedis (the Kalachuris of Tripuri), the Kosalas (possibly the Somavamshis), the Mithila (possibly a small tributary ruler), Malavas (identified with the Paramaras), the Kurus, the Kashmiris and the Gurjaras.[18] These claims appear to be exaggerated, as similar claims of extensive conquests in northern India are also found in the records of the other contemporary kings such as the Kalachuri king Yuva-Raja and the Rashtrakuta king Krishna III.[19] Yashovarman's reign marked the beginning of the famous Chandela-era art and architecture. He commissioned the Lakshmana Temple at Khajuraho.[17]

Unlike the earlier Chandela inscriptions, the records of Yashovarman's successor Dhanga (r. c. 950-999 CE) do not mention any Pratihara overlord. This indicates that Dhanga formally established the Chandela sovereignty.[20] A Khajuraho inscription claims that the rulers of Kosala, Kratha (part of Vidarbha region), Kuntala, and Simhala listened humbly to the commands of Dhanga's officers. It also claims that the wives of the kings of Andhra, Anga, Kanchi and Raḍha resided in his prisons as a result of his success in wars. These appear to be eulogistic exaggerations by a court poet, but suggest that Dhanga did undertake extensive military campaigns.[21][22] Like his predecessor, Dhanga also commissioned a magnificent temple at Khajuraho, which is identified as the Vishvanatha Temple.[23]

Dhanga's successor Ganda appears to have retained the territory he inherited.[24] His son Vidyadhara killed the Pratihara king of Kannauj (possibly Rajyapala) for fleeing his capital instead of fighting the Ghaznavid invader Mahmud of Ghazni.[25][26] Mahmud later invaded Vidyadhara's kingdom; according to the Muslim invaders, this conflict ended with Vidyadhara paying tribute to Mahmud.[27] Vidyadhara is noted for having commissioned the Kandariya Mahadeva Temple.[28]

The Chandela art and architecture reached its zenith during this period. The Lakshmana Temple (c. 930–950 CE), the Vishvanatha Temple (c. 999-1002 CE) and the Kandariya Mahadeva Temple (c. 1030 CE) were constructed during the reigns of Yashovarman, Dhanga and Vidyadhara respectively. These Nagara-style temples are representative of the most fully developed style at Khajuraho.[29]

- Nagara-style temples of Khajuraho

.jpg)

_(8638423582).jpg)

Decline

By the end of Vidyadhara's reign, the Ghaznavid invasions had weakened the Chandela kingdom. Taking advantage of this, the Kalachuri king Gangeya-deva conquered eastern parts of the kingdom.[30] Chandela inscriptions suggest that Vidyadhara's successor Vijayapala (r. c. 1035-1050 CE) defeated Gangeya in a battle.[31] However, the Chandela power started declining during the Vijayapala's reign.[32] The Kachchhapaghatas of Gwalior probably gave up their allegiance to the Chandelas during this period.[33]

Vijayapala's elder son Devavavarman was subjugated by Gangeya's son Lakshmi-Karna.[34] His younger brother Kirttivarman resurrected the Chandela power by defeating Lakshmi-Karna.[35] Kirtivarman's son Sallakshanavarman achieved military successes against the Paramaras and the Kalachuris, possibly by raiding their territories. A Mau inscription suggests that he also conducted successful campaigns in the Antarvedi region (the Ganga-Yamuna doab).[36] His son Jayavarman was of religious temperament and abdicated the throne after being tired of governance.[37]

Jayavarman appears to have died heirless, as he was succeeded by his uncle Prithvivarman, the younger son of Kirttivarman.[38] The Chandela inscriptions do not ascribe any military achievements to him; it appears that he was focused on maintaining the existing Chandela territories without adopting an aggressive expansionist policy.[39]

Revival

By the time Prithvivarman's son Madanavarman (r. c. 1128–1165 CE) ascended the throne, the neighbouring Kalachuri and Paramara kingdoms had been weakened by enemy invasions. Taking advantage of this situation, Madanavarman defeated the Kalachuri king Gaya-Karna, and possibly annexed the northern part of the Baghelkhand region.[40] However, the Chandelas lost this territory to Gaya-Karna's successor Narasimha.[41] Madanavarman also captured the territory on the western periphery of the Paramara kingdom, around Bhilsa (Vidisha). This probably happened during the reign of the Paramara king Yashovarman or his son Jayavarman.[42][43] Once again, the Chandelas could not retain the newly annexed territory for long, and the region was recaptured by Yashovarman's son Lakshmivarman.[41]

Jayasimha Siddharaja, the Chaulukya king of Gujarat, also invaded the Paramara territory, which was located between the Chandela and the Chaulukya kingdoms. This brought him in conflict with Madanavarman. The result of this conflict appears to have been inconclusive, as records of both the kingdoms claim victory.[44] A Kalanjara inscription suggests that Madanavarman defeated Jayasimha. On the other hand, the various chronicles of Gujarat claim that Jayasimha either defeated Madanavarman or extracted a tribute from him.[45] Madanavarman maintained friendly relations with his northern neighbours, the Gahadavalas.[46]

Madanavarman's son Yashovarman II either did not rule, or ruled for a very short time. Madanavarman's grandson Paramardi-deva was the last powerful Chandela king.[47]

Final decline

Paramardi (reigned c. 1165-1203 CE) ascended the Chandela throne at a young age. While the early years of his reign were peaceful, around 1182-1183 CE, the Chahamana ruler Prithviraj Chauhan invaded the Chandela kingdom. According to the medieval legendary ballads, Prithviraj's army lost its way after a surprise attack by Turkic forces, and unknowingly camped at the Chandela capital Mahoba. This led to a brief conflict between the Chandelas and the Chauhans, before Prithviraj left for Delhi. Sometime later, Prithviraj invaded the Chandela kingdom and sacked Mahoba. Paramardi cowardly took shelter in the Kalanjara fort. The Chandela force, led by Alha, Udal and other generals, was defeated in this battle. According to the various ballads, Paramardi either committed suicide out of shame or retired to Gaya.[48]

Prithviraj Chauhan's raid of Mahoba is corroborated by his Madanpur stone inscriptions. However, there are several instances of historical inaccuracies in the bardic legends. For example, it is known that Paramardi did not retire or die immediately after the Chauhan victory. He restored the Chandela power, and ruled as a sovereign until around 1202-1203 CE, when the Ghurid governor of Delhi invaded the Chandela kingdom.[49] According to Taj-ul-Maasir, a chronicle of the Delhi Sultanate, Paramardi surrendered to the Delhi forces. He promised to pay tribute to the Sultan, but died before he could keep this promise. His dewan offered some resistance to the invading forces, but was ultimately subdued. The 16th century historian Firishta states that Paramardi was assassinated by his own minister, who disagreed with the king's decision to surrender to the Delhi forces.[50]

The Chandela power did not fully recover from their defeat against the Delhi forces. Paramardi was succeeded by Trailokyavarman, Viravarman and Bhojavarman. The next ruler Hammiravarman (r. c. 1288-1311 CE) did not use the imperial title Maharajadhiraja, which indicates that the Chandela king had a lower status by his time. The Chandela power continued to decline because of the rising Muslim influence, as well as the rise of other local dynasties, such as the Bundelas, the Baghelas and the Khangars.[51]

Hammiravarman was succeeded by Viravarman II, whose titles do not indicate a high political status.[52][53] One minor branch of the family continued ruling Kalanjara: its ruler was killed by Sher Shah Suri's army in 1545 CE. Another minor branch ruled at Mahoba: Durgavati, one of its princesses married into the Gond royal family of Mandla. Some other ruling families also claimed Chandela descent (see Chandel).[54]

Art and architecture

The Chandelas are well known for their art and architecture. They commissioned a number of temples, water bodies, palaces and forts at various places. The most famous example of their cultural achievements are the Hindu and Jain temples at Khajuraho. Three other important Chandela strongholds were Jayapura-Durga (modern Ajaigarh), Kalanjara (modern Kalinjar) and Mahotsava-Nagara (modern Mahoba).[55]

- Chandela architecture

Dulhadeo temple, Khajuraho

Dulhadeo temple, Khajuraho Ajaigarh temple

Ajaigarh temple

Other smaller Chandela sites include Chandpur, Deogarh, Dudahi, Kakadeo and Madanpur.[55]

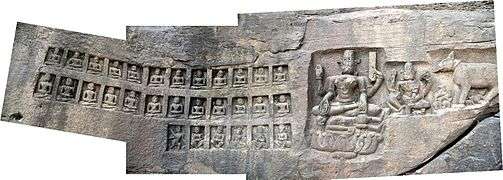

- Chandela sculptures

Brahma and his consort, Khajuraho

Brahma and his consort, Khajuraho Stone carving, Ajaigarh

Stone carving, Ajaigarh Jain tirthankaras and Sarasvati, Ajaigarh

Jain tirthankaras and Sarasvati, Ajaigarh Jain heavens, Ajaigarh

Jain heavens, Ajaigarh Jain shramanas, Ajaigarh

Jain shramanas, Ajaigarh Cattle with treasure sign, Ajaigarh

Cattle with treasure sign, Ajaigarh_(8638391942).jpg) Loving couple, Khajuraho

Loving couple, Khajuraho Surasundari Apsara, Khajuraho

Surasundari Apsara, Khajuraho Dancing Ganesha, Khajuraho

Dancing Ganesha, Khajuraho Surasundari and vyala, Khajuraho

Surasundari and vyala, Khajuraho_(8503001895).jpg) Kandariya Mahadeva temple carvings

Kandariya Mahadeva temple carvings_(8638393390).jpg) Parshvanatha temple carvings

Parshvanatha temple carvings_(8498182643).jpg) Lakshmana temple carvings

Lakshmana temple carvings

List of rulers

- ^ Harihar Vitthal Trivedi 1991, pp. 335-552.

Based on epigraphic records, the historians have come up with the following list of Chandela rulers of Jejākabhukti (IAST names in brackets):[56][57]

- Nannuka, c. 831-845 CE

- Vakpati (Vākpati), c. 845-865 CE

- Jayashakti (Jayaśakti) and Vijayashakti (Vijayaśakti), c. 865-885 CE

- Rahila (Rāhila), c. 885-905 CE

- Shri Harsha (Śri Harśa), c. 905-925 CE

- Yasho-Varman (Yaśovarman), c. 925-950 CE

- Dhanga-Deva (Dhaṅgadeva), c. 950-999 CE

- Ganda-Deva (Gaṇḍadeva), c. 999-1002 CE

- Vidyadhara (Vidyādhara), c. 1003-1035 CE

- Vijaya-Pala (Vijayapāla), c. 1035-1050 CE

- Deva-Varman, c. 1050-1060 CE

- Kirtti-Varman (Kīrtivarman), c. 1060-1100 CE

- Sallakshana-Varman (Sallakṣaṇavarman), c. 1100-1110 CE

- Jaya-Varman, c. 1110-1120 CE

- Prithvi-Varman (Pṛthvīvarman), c. 1120-1128 CE

- Madana-Varman, c. 1128-1165 CE

- Yasho-Varman II (c. 1164-65 CE); did not rule or ruled for a very short time

- Paramardi-Deva, c. 1165-1203 CE

- Trailokya-Varman, c. 1203-1245 CE

- Vira-Varman (Vīravarman), c. 1245-1285 CE

- Bhoja-Varman, c. 1285-1288 CE

- Hammira-Varman (Hammīravarman), c. 1288-1311 CE

- Vira-Varman II (an obscure ruler with low titles, attested by only one 1315 CE inscription)[52]

References

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 3.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 4.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 5.

- Jai Narayan Asopa (1976). Origin of the Rajputs. Bharatiya Publishing House. p. 208.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 6.

- Ali Javid and Tabassum Javeed (2008). World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India. 1. Algora. p. 44. ISBN 9780875864822.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 7.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 8.

- Radhey Shyam Chaurasia, History of Ancient India: Earliest Times to 1000 A. D.

- Sailendra Sen (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus. p. 22. ISBN 978-93-80607-34-4.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, pp. 27-28.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, p. 30.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 28.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, pp. 30-31.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, pp. 32-35.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, pp. 36-37.

- Sushil Kumar Sullerey 2004, p. 24.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, p. 42-51.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 42.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, p. 57.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 56.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, pp. 61-65.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 69.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, pp. 72.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, pp. 72-73.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 72.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, pp. 81-82.

- Sushil Kumar Sullerey 2004, p. 26.

- James C. Harle (1994). The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. Yale University Press. p. 234.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, pp. 89-90.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, p. 88.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 101.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, p. 90.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, p. 91.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, p. 94.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 120-121.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 126.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, pp. 110-111.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, p. 111.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 132.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 135.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, pp. 130-132.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, p. 112-113.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 133.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, pp. 133-134.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 132-133.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 130.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, pp. 120-123.

- Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, pp. 123-126.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 148.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 179.

- Peter Jackson 2003, p. 199.

- Om Prakash Misra 2003, p. 11.

- Romila Thapar 2013, p. 572.

- Sushil Kumar Sullerey 2004, p. 17.

- R. K. Dikshit 1976, p. 25.

- Sushil Kumar Sullerey 2004, p. 25.

Bibliography

- Harihar Vitthal Trivedi (1991). Inscriptions of the Paramāras (Part 2). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Volume VII: Inscriptions of the Paramāras, Chandēllas, Kachchapaghātas, and two minor dynasties. Archaeological Survey of India.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Om Prakash Misra (2003). Archaeological Excavations in Central India: Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-81-7099-874-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peter Jackson (2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54329-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- R. K. Dikshit (1976). The Candellas of Jejākabhukti. Abhinav. ISBN 9788170170464.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Romila Thapar (2013). The Past Before Us. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72651-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sisirkumar Mitra (1977). The Early Rulers of Khajurāho. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120819979.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sushil Kumar Sullerey (2004). Chandella Art. Aakar Books. ISBN 978-81-87879-32-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links