White rhinoceros

The white rhinoceros or square-lipped rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum) is the largest extant species of rhinoceros. It has a wide mouth used for grazing and is the most social of all rhino species. The white rhinoceros consists of two subspecies: the southern white rhinoceros, with an estimated 19,682–21,077 wild-living animals in the year 2015,[3] and the much rarer northern white rhinoceros. The northern subspecies has very few remaining individuals, with only two confirmed left in 2018 (two females; Fatu, 18 and Najin, 29), both in captivity. Sudan, the world's last known male northern white rhinoceros, died in Kenya on 19 March 2018.[4]

| White rhinoceros[1] | |

|---|---|

%2C_Santuario_de_Rinocerontes_Khama%2C_Botsuana%2C_2018-08-02%2C_DD_06.jpg) | |

| A white rhinoceros (C. simum) in Khama Rhino Sanctuary | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Rhinocerotidae |

| Genus: | Ceratotherium Gray, 1867 |

| Species: | C. simum |

| Binomial name | |

| Ceratotherium simum (Burchell, 1817) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

Ceratotherium simum cottoni (northern) | |

| |

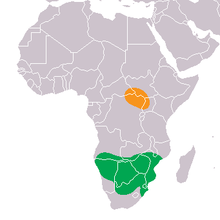

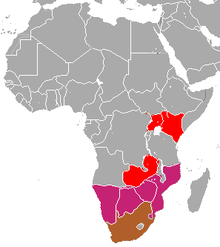

| White rhinoceros original range (orange: northern (C. s. cottoni); green: southern (C. s. simum)). | |

| |

| White rhinoceros current range (brown – native, magenta – reintroduced, red – introduced) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Naming

A popular albeit widely discredited theory of the origins of the name "white rhinoceros" is a mistranslation from Dutch to English. The English word "white" is said to have been derived by mistranslation of the Dutch word "wijd", which means "wide" in English. The word "wide" refers to the width of the rhinoceros's mouth. So early English-speaking settlers in South Africa misinterpreted the "wijd" for "white" and the rhino with the wide mouth ended up being called the white rhino and the other one, with the narrow pointed mouth, was called the black rhinoceros. Ironically, Dutch (and Afrikaans) later used a calque of the English word, and now also call it a white rhino. This suggests the origin of the word was before codification by Dutch writers. A review of Dutch and Afrikaans literature about the rhinoceros has failed to produce any evidence that the word wijd was ever used to describe the rhino outside of oral use.[5]

An alternative name for the white rhinoceros, more accurate but rarely used, is the square-lipped rhinoceros. The white rhinoceros' generic name, Ceratotherium, given by the zoologist John Edward Gray in 1868,[6] is derived from the Greek terms keras (κέρας) "horn" and thērion (θηρίον) "beast". Simum, is derived from the Greek term simos (σιμός), meaning "flat nosed".

Taxonomy and evolution

The white rhinoceros of today was said to be likely descended from Ceratotherium praecox which lived around 7 million years ago. Remains of this white rhino have been found at Langebaanweg near Cape Town.[7] A review of fossil rhinos in Africa by Denis Geraads has however suggested that the species from Langebaanweg is of the genus Ceratotherium, but not Ceratotherium praecox as the type specimen of Ceratotherium praecox should, in fact, be Diceros praecox, as it shows closer affinities with the black rhinoceros Diceros bicornis.[8] It has been suggested that the modern white rhino has a longer skull than Ceratotherium praecox to facilitate consumption of shorter grasses which resulted from the long term trend to drier conditions in Africa.[9] However, if Ceratotherium praecox is in fact Diceros praecox, then the shorter skull could indicate a browsing species. Teeth of fossils assigned to Ceratotherium found at Makapansgat in South Africa were analysed for carbon isotopes and the researchers concluded that these animals consumed more than 30% browse in their diet, suggesting that these are not the fossils of the extant Ceratotherium simum which only eats grass.[10] It is suggested that the real lineage of the white rhino should be; Ceratotherium neumayri → Ceratotherium mauritanicum → C. simum with the Langebaanweg rhinos being Ceratotherium sp. (as yet unnamed), with black rhinos being descended from C. neumayri via Diceros praecox.[8]

_-_Black_%26_White_Rhinos.png)

Recently, an alternative scenario has been proposed[11] under which the earliest African Ceratotherium is considered to be Ceratotherium efficax, known from the Late Pliocene of Ethiopia and the Early Pleistocene of Tanzania. This species is proposed to have been diversified into the Middle Pleistocene species C. mauritanicum in northern Africa, C. germanoafricanum in East Africa, and the extant C. simum. The first two of these are extinct, however, C. germanoafricanum is very similar to C. simum and has often been considered a fossil and ancestral subspecies to the latter. The study also doubts the ancestry of C. neumayri from the Miocene of southern Europe to the African species.[11] It is likely that the ancestor of both the black and the white rhinos was a mixed feeder, with the two lineages then specializing in browsing and grazing, respectively. The oldest definitive record of the White Rhinoceros is during the mid Early Pleistocene at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, around 1.8 Ma.[12]

Southern white rhinoceros

There are two subspecies of white rhino: the southern white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum simum) and the northern white rhinoceros. As of 31 December 2007, there were an estimated 17,460 southern white rhinos in the wild (IUCN 2008), making them by far the most abundant subspecies of rhino in the world; the number of southern white rhinos outnumbers all other rhino subspecies combined. South Africa is the stronghold for this subspecies (93.0%), conserving 16,255 individuals in the wild in 2007 (IUCN 2008). There are smaller reintroduced populations within the historical range of the species in Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Uganda and Swaziland, while a small population survives in Mozambique. Populations have also been introduced outside of the former range of the species to Kenya and Zambia.[13]

Wild-caught southern whites will readily breed in captivity given appropriate amounts of space and food, as well as the presence of other female rhinos of breeding age. However, for reasons that are not currently understood, the rate of reproduction is extremely low among captive-born southern white females.[14]

Northern white rhinoceros

The northern white rhinoceros or northern square-lipped rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum cottoni) is considered critically endangered and possibly extinct in the wild. Formerly found in several countries in East and Central Africa south of the Sahara, this subspecies is a grazer in grasslands and savanna woodlands.

Initially, six northern white rhinoceros lived in the Dvůr Králové Zoo in the Czech Republic. Four of the six rhinos (which were also the only reproductive animals of this subspecies) were transported to Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya,[15] where scientists hoped they would successfully breed and save this subspecies from extinction. One of two remaining in the Czech Republic died in late May 2011.[16] Both of the last two males capable of natural mating died in 2014 (one in Kenya on 18 October and one in San Diego on 15 December).[17][18] In 2015, the Kenyan government placed the last remaining male of the subspecies at Ol Pejeta under 24-hour armed guard to deter poachers, but he was put down on 19 March 2018 due to multiple health problems caused by old age, leaving just two females alive which reside at the Ol Pejeta complex. Staff hope to inseminate the remaining females with the last male's semen, although the semen is not preferable due to the age of the rhino.[19]

Following the phylogenetic species concept, recent research has led to the hypothesis that the northern white rhinoceros is a different species, rather than a subspecies of white rhinoceros as was previously thought, in which case the correct scientific name for the former should be Ceratotherium cottoni. Distinct morphological and genetic differences suggest the two proposed species have been separated for at least a million years.[20] However, the results of the research were not universally accepted by other scientists.[21]

Description

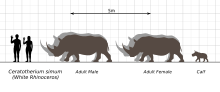

The white rhinoceros is the largest of the five living species of rhinoceros. By mean body mass, the white rhinoceros falls behind only the three extant species of elephant as the largest land animal and terrestrial mammal alive today.[22][23] It weighs slightly more on average than a hippopotamus despite a considerable mass overlap between these two species.[24] It has a massive body and large head, a short neck and broad chest.

The head and body length is 3.7 to 4 m (12.1 to 13.1 ft) in males and 3.4 to 3.65 m (11.2 to 12.0 ft) in females,[25] with the tail adding another 70 cm (28 in) and the shoulder height is 170 to 186 cm (5.58 to 6.10 ft) in the male and 160 to 177 cm (5.25 to 5.81 ft) in the female.[25] The male, averaging about 2,300 kg (5,070 lb) is heavier than the female, at an average of about 1,700 kg (3,750 lb).[25] The largest size the species can attain is not definitively known; specimens of up to 3,600 kg (7,940 lb) are considered reliable, while larger sizes up to 4,500 kg (9,920 lb) have been claimed but are not verified.[26][27][28][29] On its snout it has two horn-like growths, one behind the other. These are made of solid keratin, in which they differ from the horns of bovids (cattle and their relatives), which are keratin with a bony core, and deer antlers, which are solid bone.

.jpg)

The front horn is larger and averages 60 cm (24 in) in length, reaching as much as 150 cm (59 in) but only in females.[30] The white rhinoceros also has a noticeable hump on the back of its neck. Each of the four stumpy feet has three toes. The color of the body ranges from yellowish brown to slate grey. Its only hair is the ear fringes and tail bristles. White rhinos have a distinctive broad, straight mouth which is used for grazing. Its ears can move independently to pick up sounds, but it depends most of all on its sense of smell. The olfactory passages that are responsible for smell are larger than their entire brain. The white rhinoceros has the widest set of nostrils of any land-based animal.

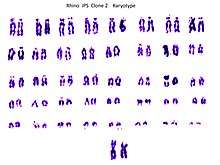

Genome and karyotype

The genome size of the white rhinoceros is 2666.62 Mbp.[31] A diploid cell has 2 x 40 autosomals and 2 sex chromosomes (XX or XY).[32]

Behavior and ecology

White rhinoceroses are found in grassland and savannah habitat. Herbivore grazers that eat grass, preferring the shortest grains, the white rhinoceros is one of the largest pure grazers. It drinks twice a day if water is available, but if conditions are dry it can live four or five days without water. It spends about half of the day eating, one third resting, and the rest of the day doing various other things. White rhinoceroses, like all species of rhinoceros, love wallowing in mud holes to cool down. The white rhinoceros is thought to have changed the structure and ecology of the savanna's grasslands. Comparatively based on studies of the African elephant, scientists believe the white rhino is a driving factor in its ecosystem. The destruction of the megaherbivore could have serious cascading effects on the ecosystem and harm other animals.[33]

.jpg)

White rhinoceroses produce sounds which include a panting contact call, grunts and snorts during courtship, squeals of distress, and deep bellows or growls when threatened. Threat displays (in males mostly) include wiping its horn on the ground and a head-low posture with ears back, combined with snarl threats and shrieking if attacked. The vocalizations of the two species differ between each other, and the panting contact calls between individual white rhinoceroses in each species can vary as well.[34] The differences in these calls aid the white rhinoceroses in identifying each other and communicating over long distances.[34] The white rhinoceros is quick and agile and can run 50 km/h (31 mph).

White rhinoceroses live in crashes or herds of up to 14 animals (usually mostly female). Sub-adult males will congregate, often in association with an adult female. Most adult bulls are solitary. Dominant bulls mark their territory with excrement and urine.[35] The dung is laid in well-defined piles. It may have 20 to 30 of these piles to alert passing rhinoceroses that it is his territory. Another way of marking their territory is wiping their horns on bushes or the ground and scrapes with its feet before urine spraying. They do this around ten times an hour while patrolling territory. The same ritual as urine marking except without spraying is also commonly used. The territorial male will scrape-mark every 30 m (98 ft) or so around its territory boundary. Subordinate males do not mark territory. The most serious fights break out over mating rights with a female. Female territory overlaps extensively, and they do not defend it.

Reproduction

Females reach sexual maturity at 6–7 years of age while males reach sexual maturity between 10–12 years of age. Courtship is often a difficult affair. The male stays beyond the point where the female acts aggressively and will give out a call when approaching her. The male chases and or blocks the way of the female while squealing or wailing loudly if the female tries to leave his territory. When ready to mate the female curls her tail and gets into a stiff stance during the half-hour copulation.[36] Breeding pairs stay together between 5–20 days before they part their separate ways. The gestation period of a white rhino is 16 months. A single calf is born and usually weighs between 40 and 65 kg (88 and 143 lb). Calves are unsteady for their first two to three days of life. When threatened, the baby will run in front of the mother, which is very protective of her calf and will fight for it vigorously. Weaning starts at two months, but the calf may continue suckling for over 12 months. The birth interval for the white rhino is between two and three years. Before giving birth, the mother will chase off her current calf. White rhinos can live to be up to 40–50 years old.[37]

Adult white rhinos have no natural predators (other than humans) due to their size,[38] and even young rhinos are rarely attacked or preyed on due to the mother's presence and their tough skin. One exceptional successful attack was perpetrated by a lion pride on a roughly half-grown white rhinoceros, which weighed 1,055 kg (2,326 lb), and occurred in Mala Mala Game Reserve, South Africa.[39]

Distribution

The southern white rhino lives in Southern Africa. About 98.5% of white rhinos live in just five countries (South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Kenya and Uganda). Almost at the edge of extinction in the early 20th century, the southern subspecies has made a tremendous comeback. In 2001 it was estimated that there were 11,670 white rhinos in the wild with a further 777 in captivity worldwide, making it the most common rhino in the world. By the end of 2007 wild-living southern white rhinos had increased to an estimated 17,480 animals (IUCN 2008).

The northern white rhino (Ceratotherium simum cottoni) formerly ranged over parts of northwestern Uganda, southern Chad, southwestern Sudan, the eastern part of Central African Republic, and northeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).[40] The last surviving population of wild northern white rhinos are or were in Garamba National Park, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)[41] but in August 2005, ground and aerial surveys conducted under the direction of African Parks Foundation and the African Rhino Specialist Group (ARSG) only found four animals: a solitary adult male and a group of one adult male and two adult females.[42][43] In June 2008 it was reported that the species may have gone extinct in the wild.[44]

Like the black rhino, the white rhino is under threat from habitat loss and poaching,[45] most recently by Janjaweed. Although there are no measurable health benefits, the horn is sought after for traditional medicine and jewelry.[45][46]

Poaching

Historically the major factor in the decline of white rhinos was uncontrolled hunting in the colonial era, but now poaching for their horn is the primary threat. The white rhino is particularly vulnerable to hunting, because it is a large and relatively unaggressive animal with very poor eye sight and generally lives in herds.

Despite the lack of scientific evidence, the rhino horn is highly prized in traditional Asian medicine, where it is ground into a fine powder or manufactured into tablets to be used as a treatment for a variety of illnesses such as nosebleeds, strokes, convulsions, and fevers. Due to this demand, several highly organized and very profitable international poaching syndicates came into being and would carry out their poaching missions with advanced technologies ranging from night vision scopes, silenced weapons, darting equipment and even helicopters. The ongoing civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo and incursions by poachers primarily coming from Sudan have further disrupted efforts to protect the few remaining northern rhinos.[47]

In 2013, poaching rates for white rhinos nearly doubled from the previous year. As a result, the white rhino has now received Near Threatened status as its total population tops out at 20,000 members. Poaching of the animal has gone virtually unchecked in most of Africa, and the non-violent nature of the rhinoceros makes it susceptible to poaching. Mozambique, one of the four main countries the white rhino lives in, is used by poachers as a passageway to South Africa, which holds a fairly large number of white rhinos. Here, rhinos are regularly killed and their horns are smuggled out of the country.[48] As of 2014, Mozambique labels white rhino poaching as a misdemeanor.[47][49]

In March, 2017 the Thoiry Zoo, located in France, was broken into by poachers. A Southern white rhinoceros named Vince was found shot dead in his enclosure; the poachers had removed one of his horns and had attempted to remove his second horn. This is believed to be the first time a rhinoceros had been killed in a European zoo.[50][51][52]

Even with increased anti-poaching efforts in many African countries, many poachers are still willing to risk death or prison time because of the tremendous amount of money that they stand to make. Rhino horn can fetch tens of thousands of dollars per kilogram on the black market in Asia and, depending on the exact price, can be worth more than its weight in gold.[53] Poachers are also starting to use social media sites for obtaining information on the location of rhino in popular tourist attractions (such as Kruger National Park) by searching for geotagged photographs posted online by unsuspecting tourists. By using GPS coordinates of rhino in recent photographs, poachers are able to more easily find and kill their targets.[54]

Modern conservation tactics

The northern white rhino is critically endangered to the point that only two of these rhinos are known to remain in the world, both in captivity.[55] Several conservation tactics have been taken to prevent this subspecies from disappearing from the planet. Perhaps the most notable type of conservation efforts for these rhinos is having moved them from Dvur Kralove Zoo in the Czech Republic to Kenya's Ol Pejeta Conservancy on 20 December 2009, where they have been under constant watch every day, and have been given favorable climate and diet, to which they have adapted well, in order to boost their chances of reproducing.

In order to save the northern white rhino from extinction, Ol Pejeta Conservancy announced that it would introduce a fertile southern white rhino from Lewa Wildlife Conservancy in February 2014. They placed the male rhino in an enclosure with both female northern white rhinos in hopes to cross-breed the subspecies. Having the male rhino with two female rhinos was expected to increase competition for the female rhinos and in theory should result in more mating experiences. Ol Pejeta Conservancy did not announce any news of rhino mating.[15][47][56]

On 22 August 2019, using (ICSI), eggs from Fatu and Najin "were successfully inseminated" using the seminal fluid from Saut and Suni. The male Sudan's sperm was harvested before his death and is still in Kenya.[57][58] On 11 September 2019, it was announced that "two embryos" were generated and will be kept in a frozen state, until placed in a surrogate female.[59][60] On 15 January 2020, it was announced that "another embryo" was created using the same techniques; all three embryos are "from Fatu".[61]

In captivity

Most white rhinos in zoos are southern white rhinos; in 2001 it was estimated that there were 777 white rhinos in captivity worldwide.

The San Diego Zoo Safari Park in San Diego, California, US had two northern white rhinos,[41][62] one of which was wild-caught. On 22 November 2015, a 41-year-old female named Nola (born in 1974), which had been on loan from the Dvůr Králové Zoo in Dvůr Králové, Czech Republic) since 1989, was euthanized after experiencing a downturn in health.[63] On 14 December 2014, a 44-year-old male named Angalifu died of old age at the San Diego Zoo.[64] The other four captive northern white rhinos were loaned to Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya, and only two remain alive. Females Najin and Fatu are still living, while males Suni and Sudan died in 2014 and 2018, respectively.[65] The northern white rhinos had been transferred to Ol Pejeta Conservancy from the Dvůr Králové Zoo in 2009 in an attempt to protect the taxa in their natural habitat.[66][67] The only two northern white rhinos left are maintained under 24-hour armed guard in Kenya.[68]

References

- Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Perissodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 634–635. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Emslie, R. (2012). Ceratotherium simum. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012.RLTS.T4185A16980466.en

- "Rhino population figures". SaveTheRhino.org. 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- "World's last male northern white rhino dies". CNN. CNN. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- Rookmaaker, Kees (2003). "Why the name of the white rhinoceros is not appropriate". Pachyderm. 34: 88–93.

- Groves, Colin P. (1972). "Ceratotherium simum". Mammalian Species (8): 1–6. doi:10.2307/3503966. JSTOR 3503966.

- Skinner, J. D. & Chimimba, Christian T. (2005). The Mammals of the Southern African Sub-region. Cambridge University Press. p. 567. ISBN 978-0-521-84418-5.

- Geraads, Denis (2005). "Pliocene Rhinocerotidae (Mammalia) from Hadar and Dikka (Lower Awash, Ethiopia), and a revision of the origin of modern African rhinos" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (2): 451–461. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0451:PRMFHA]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 4524458.

- Turner, Alan (2004). Evolving Eden: An Illustrated Guide to the Evolution of the African Large-mammal Fauna. Columbia University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-231-11944-3.

- Sponheimer, M.; Reed, K. & Lee-Thorp, J.A. (2001). "Isotopic palaeoecology of Makapansgat Limeworks Perissodactyla" (PDF). South African Journal of Science. 97: 327–328.

- Hernesniemi, E.; Giaourtsakis, I.X.; Evans, A.R. & Fortelius, M. (2011). "Chapter 11 Rhinocerotidae". In Harrison, T. (ed.). Palaeontology and Geology of Laetoli: Human Evolution in Context. Volume 2: Fossil Hominins and the Associated Fauna. Springer Science+Business Media B.V. pp. 275–294. ISBN 978-90-481-9961-7.

- Geraads, D., 2010. Rhinocerotidae, in: Werdelin, L., Sanders, W.J. (eds), Cenozoic mammals of Africa. University of California Press, Berkeley, pp. 669–683

- Emslie, R. & Brooks, M. (1999). African Rhino. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC African Rhino Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. ISBN 2-8317-0502-9.

- Swaisgood, Ron (Summer 2006). "Scientific Detective Work in Practice: Trying to Solve the Mystery of Poor Captive-born White Rhinoceros Reproduction". CRES Report. Zoological Society of San Diego. pp. 1–3.

- Northern White Rhinos. olpejetaconservancy.org

- Johnston, Raymond (2 June 2011). "White rhino dies in Czech zoo, seven left worldwide". Czech Position. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011.

- Young, Ricky (14 December 2014) Rare white rhino dies at safari park. U-T San Diego. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Drazen Jorgic (19 October 2014). "Death of rare northern white rhino leaves species on brink of extinction". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Ellis-Petersen, Hannah (20 March 2018). "Last male northern white rhino is put down". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Groves, C.P.; Fernando, P; Robovský, J (2010). "The Sixth Rhino: A Taxonomic Re-Assessment of the Critically Endangered Northern White Rhinoceros". PLoS ONE. 5 (4): e9703. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...5.9703G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009703. PMC 2850923. PMID 20383328.

- Emslie, R. (2011). "Ceratotherium simum ssp. cottoni". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T4183A10575517.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Bian, G.; Ma, L.; Su, Y.; Zhu, W. (2013). "The microbial community in the feces of the white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum) as determined by barcoded pyrosequencing analysis". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e70103. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070103.

- Cumming, D. H. M., Du Toit, R. F., & Stuart, S. N. (1990). African Elephants and Rhinos: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan: Action Plan for the Conservation of Biological Diversity 10. IUCN/SSC-AESG, Gland, Switzerland.

- Pienaar, U. de V.; Van Wyk, P.; Fairall, N. (1966). "An experimental cropping scheme of Hippopotami in the Letaba river of the Kruger National Park". Koedoe. 9 (1). doi:10.4102/koedoe.v9i1.778.

- Macdonald, D. (2001). The New Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford University Press, Oxford. ISBN 0198508239.

- Allen, Jeremiah (2010). Namibia (Other Places Travel Guide). Other Places Publishing. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-9822619-6-5.

- Newton, Michael (2009). Hidden Animals: A Field Guide to Batsquatch, Chupacabra, and Other Elusive Creatures. Greenwood Press. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-313-35906-4.

- Groves, C. P. (1972). "Ceratotherium simum". Mammalian Species. 8 (8): 1–6. doi:10.2307/3503966. JSTOR 3503966.

- Wroe, S.; Crowther, M.; Dortch, J. & Chong, J. (2004). "The size of the largest marsupial and why it matters". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 271: S34–6. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0095. JSTOR 4142550. PMC 1810005. PMID 15101412.

- Heller, E. (1913). "The white rhinoceros". Smithsonian Misc. Coll. 61 (1).

- Ceratotherium simum genome sequencing at the Broad Institute

- Stephen J. O'Brien, Joan C. Menninger and William G. Nash: Atlas of Mammalian Chromosomes John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken 2005, ISBN 9780471350156, S. 678

- Cromsigt, J. P. G. M.; Te Beest, M. (2014). "Restoration of a megaherbivore: Landscape-level impacts of white rhinoceros in Kruger National Park, South Africa". Journal of Ecology. 102 (3): 566–575. doi:10.1111/1365-2745.12218.

- Cinková, Ivana; Policht, Richard (5 June 2014). Mathevon, Nicolas (ed.). "Contact Calls of the Northern and Southern White Rhinoceros Allow for Individual and Species Identification". PLoS ONE. 9 (6): e98475. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098475. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4047034. PMID 24901244.

- Richard Estes (1991). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals: Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, Primates. University of California Press. pp. 323-. ISBN 978-0-520-08085-0.

- Owen-Smith, N. "The social system of the white rhinoceros." The behaviour of ungulates and its relation to management. IUCN, Morges (1974): 341–351.

- "Factfile: white rhino". savetherhino.org. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "Wildlife: Rhinoceros". African Wildlife Foundation. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Radloff, F. G. & Du Toit, J. T. (2004). "Large predators and their prey in a southern African savanna: a predator's size determines its prey size range". Journal of Animal Ecology. 73 (3): 410–423. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8790.2004.00817.x. JSTOR 3505651.

- Sydney, J. (1965). "The past and present distribution of some African ungulates". Transactions of the Zoological Society of London. 3 (4): 1–397. doi:10.1017/S0030605300006815.

- International Rhino Foundation. 2002. Rhino Information – Northern White Rhino. 19 September 2006.

- IUCN (7 July 2006) West African black rhino feared extinct.

- "WWF | Northern White Rhino". Worldwildlife.org. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- Smith, Lewis (17 June 2008). "News | Poachers kill last four wild northern white rhinos". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- Szabo, Christopher (9 September 2013). "Rhino poaching in Africa reaches all-time high". Environment. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "Rhino Horn Use: Fact vs. Fiction". Nature: Rhinoceros. PBS. 20 August 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "African rhino poaching crisis". WWF. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Bürger, Vicus (28 March 2015). "Stropery: Koerier praat uit". Netwerk24. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Dell'Amore, Christine (17 January 2014). "1,000+ Rhinos Poached in 2013:Highest in Modern History". National Geographic. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "Poachers Kill Rhino in Brazen Attack at French Zoo". 7 March 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "Poachers kill rhino for his horn at French zoo". BBC News. 7 March 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "Poachers Break into French Zoo, Kill White Rhino And Steal His Horn". NPR. 7 March 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Gwin, Peter (March 2012). "Rhino Wars". National Geographic. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Stampler, Laura (7 May 2014). "Stick to Foodstagramming: Poachers May Be Following Your Safari Pictures". Time. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Sullivan, Deborah (20 December 2014). "Scientists seek to create new rhinos with stem cell technology". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "Male Southern White Rhino Introduced in Endangered Species Boma". Ol Pejeta Conservancy. 12 February 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Ciaccia, Chris (26 August 2019). "Northern white rhino eggs successfully fertilized". Fox News. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- Fortin, Jacey (28 August 2019). "Scientists Fertilize Eggs From the Last Two Northern White Rhinos". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- Dahir, Abdi Latif (11 September 2019). "Scientists have successfully created embryos of the near-extinct northern white rhino". Quartz Africa. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "Living on the brink". BBC Earth. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- Anna, Cara (15 January 2020). "'Amazing': New embryo made of nearly extinct rhino species". Star Tribune. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Eastman, Q. (2007) Northern white rhinos in danger. North County Times (11 June 2007) via Web Archive.

- "Endangered white rhino dies at San Diego Zoo". Fox News. AP. 22 November 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Ohlheiser, Abby (15 December 2014). "A northern white rhino has died. There are now five left in the entire world". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "ZOO Dvůr Králové – Severní bílý nosorožec Suni v Keni uhynul". zoodvurkralove.cz (in Czech). Archived from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "Události ČT: Ve Dvoře Králové oplakávají Nabiré" (in Czech). CT24. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "Northern White Rhinos | Ol Pejeta Conservancy". olpejetaconservancy.org. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Svenska, Anneka; Ross, Tom (16 August 2019). The Last Two Northern White Rhinos in the World. Animal Watch (Documentary). Event occurs at 1:36–1:46. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ceratotherium simum. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Ceratotherium simum |

- White Rhino Info & White Rhino Pictures on the Rhino Resource Center website.

- White Rhino entry on International Rhino Foundation website.

- White Rhino entry on World Wide Fund for Nature website.

- White Rhinoceros entry on IUCN Red List.

- Honolulu Zoo

- San Diego Zoo

- Philadelphia Zoo

- Narrated video about the White Rhinoceros

- White Rhino description

- First test tube White Rhinoceros born at Budapest Zoo

- Poachers kill one of last two white rhinos in Zambia

- Rhino Webcam at Zoo Budapest

- New baby rhino from frozen sperm – Madrid

- "Rare White Rhino Dies, Leaving Only Four Left on the Planet". news.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- View the cerSim1 genome assembly in the UCSC Genome Browser.

- People Not Poaching: The Communities and IWT Learning Platform