Spanish object pronouns

Spanish object pronouns are Spanish personal pronouns that take the function of an object in a sentence. They may be analyzed as clitics which cannot function independently, but take the conjugated form of the Spanish verb.[1] Object pronouns are generally proclitic, i.e. they appear before the verb of which they are the object; enclitic pronouns (i.e. pronouns attached to the end of the verb) appear with positive imperatives, infinitives, and gerunds.

| Spanish language |

|---|

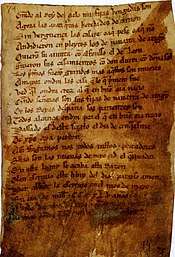

Spanish around the 13th century |

| Overview |

| History |

|

| Grammar |

| Dialects |

| Dialectology |

| Interlanguages |

| Teaching |

In Spanish, up to two (or rarely three) clitic pronouns can be used with a single verb, generally one accusative and one dative. They follow a specific order based primarily on person. When an accusative third-person non-reflexive pronoun (lo, la, los, or las) is used with a dative pronoun that is understood to also be third-person non-reflexive. Simple non-emphatic clitic doubling is most often found with dative clitics, although it is occasionally found with accusative clitics as well, particularly in case of topicalization. In many dialects in Central Spain, including that of Madrid, there exists one of the variants of leísmo, which is using the indirect object pronoun le for the object pronoun where most other dialects would use lo (masculine) or la (feminine) for the object pronoun.

History

As the history of the Spanish language saw the shedding of Latin declensions, only the subject and prepositional object survived as independent personal pronouns in Spanish: the rest became clitics. These clitics may be proclitic or enclitic, or doubled for emphasis.[2] In modern Spanish, the placement of clitic pronouns is determined morphologically by the form of the verb. Clitics precede most conjugated verbs but come after infinitives, gerunds, and positive imperatives. For example: me vio but verme, viéndome, ¡véame! Exceptions exist for certain idiomatic expressions, like "once upon a time" (Érase una vez).[1]

| Case | Latin | Spanish |

|---|---|---|

| 1st sg. |

EGŌ (Nominative) |

yo (Nominative) |

| 1st pl. | NŌS (Nominative/Accusative) |

nosotros, nosotras (Nominative/Prepositional) |

| 2nd sg. |

TŪ (Nominative) |

tú (Nominative) |

| 2nd pl. | VŌS (Nominative/Accusative) |

vosotros, vosotras (Nominative/Prepositional) |

| 3rd sg. |

ILLE, ILLA, ILLUD (Nominative) |

él/ella/ello (Nominative/Prepositional) |

| 3rd pl. |

ILLĪ, ILLAE, ILLA (Nominative) |

ellos/ellas (Nominative/Prepositional) |

| 3rd refl. (sg. & pl.) |

SIBI (Dative) |

sí (Prepositional) |

Old Spanish

Unstressed pronouns in Old Spanish were governed by rules different from those in modern Spanish.[2] The old rules were more determined by syntax than by morphology:[1] the pronoun followed the verb, except when the verb was preceded (in the same clause) by a stressed word, such as a noun, adverb, or stressed pronoun.[2]

For example, from Cantar de Mio Cid:

- e tornós pora su casa, ascóndense de mio Cid

- non lo desafié, aquel que gela diesse[2]

If the first stressed word of a clause was in the future or conditional tense, or if it was a compound verb made up of haber + a participle, then any unstressed pronoun was placed between the two elements of the compound verb.[2]

- daregelo he (modern: se lo daré) = "I'll give it to him".

- daregelo ia/ie (modern: se lo daría) = "I would give it."

- dado gelo ha (modern: se lo ha dado) = "He has given it."[2]

Before the 15th century, clitics never appeared in the initial position; not even after a coordinating conjunction or a caesura. They could, however, precede a conjugated verb if there was a negative or adverbial marker. For example:

- Fuese el conde = "The count left", but

- El conde se fue = "The count left"

- No se fue el conde = "The count did not leave"

- Entonces se fue el conde = "Then the count left".[1]

The same rule applied to gerunds, infinitives, and imperatives. The forms of the future and the conditional functioned like any other verb conjugated with respect to the clitics. But a clitic following a future or conditional was usually placed between the infinitive root and the inflection. For example:

- Verme ha mañana = "See me tomorrow", but

- No me verá mañana = "He will not see me tomorrow"

- Mañana me verá = "He will see me tomorrow"[1]

Early Modern Spanish

By the 15th century, Early Modern Spanish had developed "proclisis", in which an object's agreement markers come before the verb. According to Andrés Enrique-Arias, this shift helped speed up language processing of complex morphological material in the verb's inflection (including time, manner, and aspect).[3]

This proclisis (ascenso de clítico) was a syntactic movement away from the idea that an object must follow the verb. For example, in these two sentences with the same meaning:[4]

- María quiere comprarlo = "Maria wants to buy it."

- María lo quiere comprar = "Maria wants to buy it."

"Lo" is the object of "comprar" in the first example, but Spanish allows that clitic to appear in a preverbal position of a syntagma that it dominates strictly, as in the second example. This movement only happens in conjugated verbs. But a special case occurs for the imperative, where we see the postverbal position of the clitic

- Llámame = "Call me"

- dímelo = "Tell it to me"

This is accounted for by a second syntactic movement wherein the verb "passes by" the clitic that has already "ascended".

Clitic substitution for the accusative

In most cases, one can identify the direct object of a Spanish sentence by substituting it for the accusative personal pronouns "lo", "la", "los", and "las".

- Aristóteles instruyó a Alejandro = "Aristotle instructed Alexander"

- Aristóteles lo instruyó = "Aristotle instructed him"

But "lo" (only in its masculine and singular form) can also replace an attributive adjective, so it is necessary to identify first whether the sentence is predicative or attributive. An example of the attributive:

- Roma es valiente = "Rome is brave"

- Roma lo es = "Rome is [brave]"

The "¿Qué?" method

Traditional Spanish grade school language pedagogy teaches that one may identify the direct object by asking the question "What?" ("¿Qué?"). But this method is not always reliable, because the answer to the question "what" may be the subject:

- La nave surca el mar = "The ship crosses the sea"

- ¿Qué surca? > "La nave." = "What crosses?" "The ship."

This method also fails to analyze question sentences:

- ¿Qué pueblos sometió César? = "Which peoples did Caesar conquer?"

- ¿Qué sometió? > ... (nonsensical, "What conquers?")

Mandatory proclitic

Object pronouns are generally proclitic, i.e. they appear before the verb of which they are the object. Thus:

- Yo te veo = "I see you" (lit. "I you see")

- Él lo dijo = "He said it" (lit. "He it said")

- Tú lo has hecho = "You have done it" (lit. "You it have done")

- El libro nos fue dado = "The book was given to us" (lit. "The book us was given")

Mandatory enclitic

In certain environments, however, enclitic pronouns (i.e. pronouns attached to the end of the verb or similar word itself) may appear. Enclitization is generally only found with:

- positive imperatives

- infinitives

- gerunds

With positive imperatives, enclitization is always mandatory:

- Hazlo ("Do it") but never Lo haz

- Dáselo a alguien diferente ("Give it to somebody else") but never Se lo da a alguien diferente (as a command; that sentence can also mean "He/she/it gives it to somebody else", in which sense it is entirely correct)

With infinitives and gerunds, enclitization is often, but not always, mandatory. With all bare infinitives, enclitization is mandatory:

- tenerlo = "to have it"

- debértelo = "to owe it to you"

- oírnos = "to hear us"

In all compound infinitives that make use of the past participle (i.e. all perfect and passive infinitives), enclitics attach to the uninflected auxiliary verb and not the past participle (or participles) itself:

- haberlo visto = "to have seen it"

- serme guardado = "to be saved for me"

- habértelos dado = "to have given them to you"

- haberle sido mostrado = "to have been shown to him/her/you"

In all compound infinitives that make use of the gerund, however, enclitics may attach to either the gerund itself or the main verb, including the rare cases when the gerund is used together with the past participle in a single infinitive:

- estar diciéndolo or estarlo diciendo = "to be saying it"

- andar buscándolos or andarlos buscando = "to go around looking for them"

- haber estado haciéndolo or haberlo estado haciendo = "to have been doing it"

With all bare gerunds, enclitization is once again mandatory. In all compound gerunds, enclitics attach to the same word as they would in the infinitive, and one has the same options with combinations of gerunds as with gerunds used in infinitives:

- haciéndolo = "doing it"

- hablándoles = "talking to them"

- habiéndolo visto = "having seen it"

- siéndome dado = "being given to me"

- habiéndole sido mostrado = "having been shown to him/her/you"

- habiendo estado teniéndolos or habiéndolos estado teniendo = "having been holding them"

- andando buscándolos or andándolos buscando = "going around looking for them"

Proclitic or enclitic

In constructions that make use of infinitives or gerunds as arguments of a conjugated verb, clitic pronouns may appear as proclitics before the verb (as in most verbal constructions, or, in the case of positive imperatives, as enclitics attached to it) or simply as enclitics attached to the infinitive or gerund itself. Similarly, in combinations of infinitives, enclitics may attach to any one of them:

- Quería hacerlo or Lo quería hacer = "He wanted to do it"

- Estoy considerándolo or Lo estoy considerando = "I'm considering it"

- Empieza a hacerlo or Empiézalo a hacer = "Start doing it"

- Sigue diciéndolo or Síguelo diciendo = "Keep saying it"

- querer vernos or querernos ver = "to want to see us"

- tener que poder hacerlo, tener que poderlo hacer, or tenerlo que poder hacer = "to have to be able to do it"

Enclitics may be found in other environments in literary and archaic language, but such constructions are virtually absent from everyday speech.

Metaplasm

Enclitization is subject to the following metaplasmic rules:

- The s in the first-person plural ending -mos drops before nos, se, and os: vámonos ("let's go"), démoselo ("let's give it to him"), mostrémoos ("let's show you [pl.]"), etc.

- The d in the informal second-person plural positive imperative drops before os: sentaos ("[you all] sit down"), apuraos ("[you all] hurry up"), suscribíos[5] ("[you all] subscribe"), etc., except for the verb ir: idos ("[you all] leave")

Combinations of clitic pronouns

In Spanish, up to two (and rarely three) clitic pronouns can be used with a single verb, generally one accusative and one dative. Whether enclitic or proclitic, they cluster in the following order:[6] [7]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| se | te os | me nos | lo, la, los, las, le, les |

Thus:

- Él me lo dio = "He gave it to me"

- Ellos te lo dijeron = "They said it to you"

- Yo te me daré = "I will give myself to you"

- Vosotros os nos mostráis = "You [pl.] are showing yourselves to us"

- Se le perdieron los libros = "The books disappeared on him" (lit. "The books got lost to him")

Like Latin, Spanish makes use of double dative constructions, and thus up to two dative clitics can be used with a single verb. One must be the dative of benefit (i.e. someone (or something) who is indirectly affected by the action), and the other must refer to the direct recipient of the action itself. Context is generally sufficient to determine which is which:

- Me le arreglaron la moto = roughly "They fixed the bike [motorcycle] for him on my behalf" or "They fixed the bike for me on his behalf" (literally more like "They fixed the bike for him for me" or vice versa)

- Muerte, ¿por qué te me lo llevaste tan pronto? = "Death, why did you take him from me so soon?"

Only one accusative clitic can be used with a single verb, however, and the same is true for any one type of dative clitic. When more than one accusative clitic or dative clitic of a specific type is used with a verb, therefore, the verb must be repeated for each clitic of the same case used:

- Me gusta y te gusta but never Me y te gusta = "You and I like him" (lit. "He pleases you and me")

- Lo vi y te vi but never Lo y te vi = "I saw him and you"

Occasionally, however, with verbs such as dejar ("to let"), which generally takes a direct object as well as a subsequent verb as a further grammatical argument, objects of two different verbs will appear together with only one of them and may thus appear to be objects of the same verb:

- Me la dejaron ver = "They let me see her" (la is the object of ver; Me dejaron verla is thus also acceptable)

- Te lo dejará hacer = "He/she will let you do it" (Te dejará hacerlo is also acceptable)

Se

When an accusative third-person non-reflexive pronoun (lo, la, los, or las) is used with a dative pronoun that is understood to also be third-person non-reflexive (le or les), the dative pronoun is replaced by se:

- Se lo di = "I gave it to him"

- Él se lo dijo = "He said it to him"

If se as such is the indirect object in similar constructions, however, it is often, though not always, disambiguated with a sí:

- Se lo hizo a sí or Se lo hizo = "He did it to himself"

- Se lo mantenían a sí or Se lo mantenían = "They kept it for themselves"

Clitic doubling

Non-emphatic

Simple non-emphatic clitic doubling is most often found with dative clitics. It is found with accusative clitics as well in cases of topicalization, and occasionally in other cases.

All personal non-clitic direct objects, as well as indirect objects, must be preceded by the preposition a. Therefore, to distinguish the non-clitic indirect objects, an appropriate dative clitic pronoun is often used. This is done even with non-personal things such as animals and inanimate objects. With all non-clitic dative personal pronouns, which take the form a + the prepositional case of the pronoun, and all non-pronominal indirect objects that come before the verb, in the active voice, clitic doubling is mandatory:[6]

- A mí me gusta eso but never A mí gusta eso = "I like that" (lit. "That pleases me")

- Al hombre le dimos un regalo but never Al hombre dimos un regalo = "We gave the man a gift"

- Al perro le dijo que se siente but never Al perro dijo que se siente = "He/She/You told the dog to sit"

With non-pronominal indirect objects that come after the verb, however, clitic doubling is usually optional, though generally preferred in spoken language:

- Siempre (les) ofrezco café a mis huéspedes = "I always offer coffee to my guests"

- (Le) Dijeron a José que se quedara donde estaba = "They told Jose to stay where he was"

- (Le) Diste al gato alguna comida = "You gave the cat some food"

Nevertheless, with indirect objects that do not refer to the direct recipient of the action itself as well as the dative of inalienable possession, clitic doubling is most often mandatory:

- No le gusta a la mujer la idea but never No gusta a la mujer la idea = "The woman doesn't like the idea" (lit. "The idea doesn't please the woman")

- Le preparé a mi jefe un informe but never Preparé a mi jefe un informe = "I prepared a report for my boss"

- Les cortó a las chicas el pelo but never Cortó a las chicas el pelo = "He/She/You cut the girls' hair" (dative of inalienable possession, cannot be literally translated into English)

With indefinite pronouns, however, clitic doubling is optional even with such dative constructions:

- Esta película no (le) gusta a nadie = "No one likes this movie" (lit. "This move pleases no one")

- (Les) Preparó esta comida a todos = "He/she/you made this food for everyone"

In the passive voice, where direct objects do not exist at all, simple non-emphatic dative clitic doubling is always optional, even with personal pronouns:

- (Le) Era guardado a mi amigo este pedazo = "This piece was saved for my friend"

- (Te) Fue dado a ti = "It was given to you"

Dative clitic personal pronouns may be used without their non-clitic counterparts, however:

- Él te habló = "He spoke to you"

- Se lo dieron = "They gave it to him/her/you"

- Nos era guardado = "it was saved for us"

Simple non-emphatic clitic doubling with accusative clitics is much rarer. It is generally only found with:

- the pronoun todo ("all, everything")

- numerals that refer to animate nouns (usually people) and are preceded by the definite article (e.g. los seis – "the six")

- the indefinite pronoun uno when referring to the person speaking

Thus:

- No lo sé todo = "I don't know everything"

- Los vi a los cinco = "I saw the five (of them)"

- Si no les gusta a ellos, lo rechazarán a uno = "If they don't like it, they'll reject you"

Accusative clitic doubling is also used in object-verb-subject (OVS) word order to signal topicalization. The appropriate direct object pronoun is placed between the direct object and the verb, and thus in the sentence La carne la come el perro ("The dog eats the meat") there is no confusion about which is the subject of the sentence (el perro).

Clitic doubling is also often necessary to modify clitic pronouns, whether dative or accusative. The non-clitic form of the accusative is usually identical to that of the dative, although non-clitic accusative pronouns cannot be used to refer to impersonal things such as animals and inanimate objects. With attributive adjectives, nouns (appositionally, as in "us friends"), and the intensifier mismo, clitic doubling is mandatory, and the non-clitic form of the pronoun is used:

- Te vi a ti muy feliz = "I saw a very happy you"

- Os conozco a vosotros gente (or, in Latin America, Los conozco a ustedes gente) = "I know you people"

- Le ayudaron a ella misma = "They helped her herself" (ayudar governs the dative)

With predicative adjectives, however, clitic doubling is not necessary. Clitic pronouns may be directly modified by such adjectives, which must be placed immediately after the verb, gerund, or participle (or, if used in combination or series, the final verb, gerund, or participle):

- Mantente informado = "Keep yourself informed"

- Viéndolo hecho en persona, aprendí mucho = "By seeing it done in person, I learned a lot"

- Lo había oído dicho a veces = "He/she/you had heard it said occasionally"

Emphatic

Clitic doubling is also the normal method of emphasizing clitic pronouns, whether accusative or dative. The clitic form is used in the normal way, and the non-clitic form is placed wherever one wishes to place emphasis:

- Lo vi a él = "I saw him"

- Te ama a ti = "He loves you"

- A ella le gusta la idea = "She likes the idea" (lit. "The idea pleases her")

Because non-clitic accusative pronouns cannot have impersonal antecedents, however, impersonal accusative clitics must be used with their antecedents instead:

- Se las di las cosas but never Se las di ellas = "I gave the things (them) to her"

- Lo vi el libro but never Lo vi él = "I saw the book (it)"

Impersonal dative clitic pronouns, however, may be stressed as such:

- Se lo hiciste a ellos = "You did it to them"

- Esto le cabe a ella = "This fits it [feminine noun]"

Emphatic non-pronominal clitic doubling is also occasionally used to provide a degree of emphasis to the sentence as a whole:

- Lo sé lo que dijo = "I know what he/she/you said" (with a degree of emphasis)

- ¡Lo hace el trabajo! ¡Déjalo solo! = "He's doing his work! Leave him alone!"

Prepositional and comitative cases

The prepositional case is used with the majority of prepositions: a mí, contra ti, bajo él, etc., although several prepositions, such as entre ("between, among") and según ("according to"), actually govern the nominative (or sí in the case of se): entre yo y mi hermano ("between me and my brother"), según tú ("according to you"), entre sí ("among themselves"), etc., with the exception of entre nos ("between us"), where the accusative may be used instead (entre nosotros is also acceptable). With the preposition con ("with"), however, the comitative case is used instead. Yo, Tú, and se have distinct forms in the comitative: conmigo, contigo, and consigo, respectively, in which the preposition becomes one word with its object and thus must not be repeated by itself: conmigo by itself means "with me", and con conmigo is redundant. For all other pronouns, the comitative is identical to the prepositional and is used in the same way: con él, con nosotros, con ellos, etc.

As often with verbs used with multiple object pronouns of the same case, prepositions must be repeated for each pronoun they modify:

- Este vino es solamente para mí y para ti but never Este vino es solamente para mí y ti = "This wine is only for me and (for) you"

- Ella estaba con él y con ella but never Ella estaba con él y ella = "She was with him and (with) her"

Notes

- Pountain, Christopher J. (2001). A History of the Spanish Language Through Texts. Routledge. pp. 177, 264–5. ISBN 978-0-415-18062-7.

- Penny, Ralph J. (1991). A History of the Spanish Language. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 119, 123. ISBN 978-0-521-39481-9.

- Asín, Jaime Oliver (1941). Diana Artes Gráficas (ed.). Historia de la lengua española (6th ed.). Madrid. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-0-415-18062-7.

- Zagona, Karen (2002). The Syntax of Spanish. Cambridge Syntax Guides. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 185–90. ISBN 978-0-521-57684-0.

- Note: With reflexive verbs ending in -ir, it is necessary to drop the d in the vosotros imperative due to metaplasm (as with -ar and -er verbs), and it is also necessary to add an acute accent to the i in order to break the diphthong. This is shown in the example suscribíos, which is the vosotros positive imperative of suscribirse.

- "Pronombres Personales Átonos" [Unstressed Personal Pronouns]. Diccionario panhispánico de dudas [Pan-Hispanic Dictionary of Doubts] (in Spanish). Real Academia Española. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- Perlmutter, David M. (1971). Deep and surface structure constraints in syntax. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0030840104. OCLC 202861.

Bibliography

- Nueva Gramática de la Lengua Española, Espasa, 2009.

- Gramática descriptiva de la Lengua Española, Ignacio Bosque y Violeta Demonte, Espasa, 1999.