Carsharing

Carsharing or car sharing (AU, NZ, CA, TH, & US) or car clubs (UK) is a model of car rental where people rent cars for short periods of time, often by the hour. It differs from traditional car rental in that the owners of the cars are often private individuals themselves, and the carsharing facilitator is generally distinct from the car owner. Carsharing is part of a larger trend of shared mobility.

Carsharing enables an occasional use of a vehicle or access to different brands of vehicles. The renting organization may be a commercial business. Users can also organize as a company, public agency, cooperative, or ad hoc grouping. The network of cars on the network becomes available to the users through a variety of means, ranging from the simplicity of using an app to unlock the car in real time, to meeting the owner of the car in order to exchange keys. As of January 2020 the world's top city for car-sharing is Moscow with more than 30,000 vehicles.[1]

History

Early days

The first reference to carsharing in print identifies the Selbstfahrergenossenschaft carshare program in a housing cooperative that got underway in Zürich in 1948,[2][3] but there was no known formal development of the concept in the next few years. By the 1960s, as innovators, industrialists, cities, and public authorities studied the possibility of high-technology transportation – mainly computer-based small vehicle systems (almost all of them on separate guideways) – it was possible to spot some early precursors to present-day service ideas and control technologies.

The early 1970s saw the first whole-system carshare projects. The ProcoTip system in France lasted only about two years. A much more ambitious project called the Witkar was launched in Amsterdam by the founders of the 1965 white bicycles project. A sophisticated project based on small electric vehicles, electronic controls for reservations and return, and plans for a large number of stations covering the entire city, the project endured into the mid-1980s before finally being abandoned.

In July 1977, the first official British experiment in carsharing started in Suffolk. An office in Ipswich provided a Share-a-Car service for "putting motorists who are interested in sharing car journeys in touch with each other."[4] In 1978, the Agricultural Research Council granted the University of Leeds £16,577 "for an investigation and simulation of carsharing".[5] The scheme was not intended for different drivers of a single car but for a driver offering seats in his car.

The 1980s and first half of the 1990s was a "coming of age" period for carsharing, with continued slow growth, mainly of smaller non-profit systems, many in Switzerland and Germany[6] but also on a smaller scale in Canada, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United States.[7]

Carsharing in North America was founded in Quebec City in 1994 by Benoît Robert, with a company called Communauto that is still a leader in carsharing globally. Cycling advocate and environmentalist Claire Morissette (1950–2007) played a major role in its evolution starting in 1995, when Communauto established itself in Montreal as a private company. The company goal is to provide a convenient and economical alternative to owning a car.

In 2005, a novel form of car sharing service, the "Libre Service Integral", later knowed as Free Floating, has been introduce by VULOG and tested from 2007 in Antibes CiteVU mobility service, on the french riviera. An electric car paid by minute, when and how long I need, where I want and where I go". This service was added to Communauto in 2012.

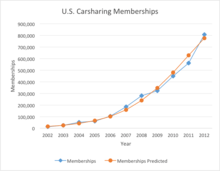

Boom in the United States

Zipcar, Flexcar (bought by Zipcar in 2007), and City Car Club were all started in 2000. City CarShare was founded in the San Francisco Bay Area in 2001, as a non-profit. Several car rental companies launched their own carsharing services beginning in 2008, including Avis on Location by Avis, Hertz on Demand (formerly known as Connect by Hertz[8]), operating in the U.S. and Europe; Uhaul Car Share owned by U-Haul, and WeCar by Enterprise Rent-A-Car.[9] By 2010, when various peer-to-peer carsharing systems were introduced. As of September 2012[10] Zipcar accounted for 80% of the U.S carsharing market[9][11] and half of all car-sharers worldwide[12] with 730,000 members sharing 11,000 vehicles.

In 2008, City CarShare introduced the first wheelchair carrying car share vehicle, the Access Mobile, specifically designed as a fleet vehicle shared with non-wheelchair users.

Carsharing is noted as a tool for achieving VMT and GHG reduction targets in the California Transport Plan (CTP) 2040 to reduce congestion and pollution.[13]

Development and growth

| city | fleet in units |

|---|---|

| Tokyo | 19.800 |

| Moscow | 16.500 |

| Beijing | 15.400 |

| Shanghai | 13.900 |

| Guangzhou | 4.200 |

Carsharing has also spread to other global markets with dense urban populations (such as Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Mexico, Russia and Turkey) given that population density is often a critical determinant of success for carsharing.[15] Successful carsharing development has tended to be associated mainly with densely populated areas, such as city centers and more recently university and other campuses. There are some programs (mostly in Europe) for providing services in lower density and rural areas. Low-density areas are considered more difficult to serve with carsharing because of the lack of alternative modes of transportation and the potentially larger distance that users must travel to reach the cars.

Many building developers are now incorporating share-cars into their developments as an added value to tenants, and municipal government bodies around the world are starting to stipulate the implementation of a carsharing service in new buildings, as a sustainability initiative. These trends have created a demand for a new model of carsharing – residential, private-access share-cars that are typically underwritten by the Homeowner association. In Germany a pilot project has been started by the semiconductor manufacturer Infineon to replace regular pool vehicles with a corporate carsharing system.[16] Replacing private automobiles with shared ones directly reduces demand for parking spaces. The fact that only a certain number of cars can be in use at any one time may reduce traffic congestion at peak times. Even more important for congestion, the strong metering of costs provides a cost incentive to drive less. With owned automobiles many expenses are sunk costs and thus independent of how much the car is driven (such as original purchase, insurance, registration, and some maintenance).

According to Navigant Consulting, global carsharing services revenue is expected to grow to US$6.2 billion by 2020, with over 12 million members worldwide. The main factors driving the growth of carsharing are the rising levels of congestion faced by city dwellers; shifting generational mindsets about car ownership; the increasing costs of personal vehicle ownership; and a convergence of business models.[17][18] Carsharing operators increasingly opt to brand parts of their fleets with third-party advertising in order to increase revenue and improve competitiveness (Transit media).

For future applications, many carsharing companies invest in plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEV) to reduce gas consumption. One idea is to calculate and compensate all emissions on behalf of your drivers according to the Kyoto protocol, e.g. via reforestation schemes. The world's first certified carbon neutral carsharing service is Respiro carsharing in Madrid[19] and is also done by Australian p2p car sharing platform Car Next Door.

The most important technological innovation to affect the carsharing market is self-driving cars. It is expected that most self-driving vehicles won't be owned by individuals, but will rather be shared. Some companies, like Ernst & Young, have also started to use blockchain technology to record ownership, usage of shared vehicles and insurance information.[20]

In July 2018, Volkswagen announced its intention to launch an all-electric car-sharing service by 2019.[21] In August 2018, the carsharing startup Getaround rose $300 million from Softbank.[22] According to Moscow's authority, the number of carsharing journeys in the city averaged 30,000 a day between January and September 2018.[23]

Global development and comparison in urban regions

Car-sharing is growing in urban regions as more people around the world adopt it.[24] The world's top cities for car-sharing in 2018 were Tokyo (Japan) with 19.8K vehicles, Moscow (Russia) with 16.5K vehicles, Beijing (China) with 15.4K vehicles, Shanghai (China) with 13.9K vehicles, Guangzhou (China) with 4.2K vehicles.[25]

Types of carsharing

Generally, carsharing programs fall into one of four sharing models: roundtrip, one-way, peer-to-peer, or fractional.

Roundtrip carsharing

Members begin and end their trip at the same location, often paying by the hour, mile, or both.

One-way/free-floating carsharing

One-way carsharing enables users to begin and end their trip at different locations through free floating zones or station-based models with designated parking locations.[26] As of 2017, free-floating carsharing is available in 55 cities and 20 countries worldwide, with 40,000 vehicles and serving 5.6 million users, with Europe and North America representing the majority of the market. In Europe, free floating services took up more than 65 percent in carsharing membership.[27]

The service is expected to reach 14.3 million users with more than 100,000 vehicles by the end of 2022.[28]

Peer-to-peer carsharing

Peer-to-peer carsharing, sometimes referred to as P2P or Personal Vehicle Sharing,[26] operates similarly to roundtrip carsharing in trip and payment type. However, the vehicles themselves are typically privately owned or leased with the sharing system operated by a third-party.

Fractional ownership

Fractional ownership allows users to co-own a vehicle and share its costs and use.[29] Neighborhood fractional ownership carsharing is often promoted as an alternative to owning a car where public transit, walking, and cycling can be used most of the time and a car is only necessary for out-of-town trips, moving large items, or special occasions. It can also be an alternative to owning multiple cars for households with more than one driver.[30]

Difference with traditional car rentals

Carsharing differs from traditional car rentals in the following ways:

- Carsharing is not limited by office hours

- Reservation, pickup, and return is all self-service

- Vehicles can be rented by the minute, by the hour, as well as by the day

- Users are members and have been pre-approved to drive (background driving checks have been performed and a payment mechanism has been established).

- Vehicle locations are distributed throughout the service area, and often located for access by public transport.

- Insurance: state minimum liability insurance (only $5000 in some states), comprehensive and collision insurance. They do not provide uninsured, under-insured or personal injury protection insurance.

- Fuel costs are included in the rates.

- Vehicles are not serviced (cleaning, fueling) after each use, although certain programs (such as Car2Go or GoGet) continuously clean and fuel their fleet.

With carsharing, individuals have access to private cars without having costs and responsibilities associated with car ownership (except for fractional ownerships).[31] Some carshare operations (CSOs) cooperate with local car rental firms, in particular in situations wherein classic rental may be the cheaper option.

The insurance policies on carsharing greatly varies among companies, but all carsharing firms provide insurance that at least meets the legal minimum requirements for the given region of operation. Rob Lieber of The New York Times has criticized carsharing firms such as Zipcar for the paltry coverage afforded carsharing drivers.[32]

Technology

The technology of CSOs varies enormously, from simple manual systems using key boxes and log books to increasingly complex computer-based systems (e.g. partially automated and fully automated systems) with supporting software packages that handle a growing array of back office functions.[34] The simplest CSOs have only one or two pick-up points, but more advanced systems allow cars to be picked up and dropped off at any available public parking space within a designated operating area.

Once the reservations are completed and confirmed, the car will then be delivered at the time and place scheduled. There will be a small card reader mounted on the windshield. Once the customer places their membership card on the reader, it will use what is called blink technology to activate the time and unlock the car. The reader will not work until it is time for that specific reservation. The keys can then be found somewhere inside the car such as the glove compartment. Depending on the company, the customer may be provided with a key to a lock box that contains the ignition key itself.[35] In some cases the car can be unlocked using a mobile phone and the car can even be started using the phone as well.

Many car sharing networks price their services as a small start up fee and then a milage fee for the distance driven in the car. Usually the app will include insurance, gas cards, and upkeep to their fleet of cars at no additional charge to the customer.

International terminology

See also

- Access economy

- Alternatives to the automobile

- Car rental

- Carpooling

- Ecoleasing

- Fleet vehicle

- List of carsharing organizations

- Ridesharing company

References

- Москва вышла в мировые лидеры по парку каршеринга

- "The CarSharing Handbook (Part 1)". Rain Magazine. Archived from the original on 20 July 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Shaheen, Susan; Sperling, Daniel; Wagner, Conrad (1998). "Carsharing in Europe and North America: Past, Present and Future" (PDF). 52 (3). Transportation Quarterly: 35–52. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Young, Robin (19 July 1977). "Experiment in car-sharing". The Times. p. 2.

- The Times, 15 February 1978, p. 12

- "The early days of car-sharing". Rain Magazine. 1994.

- Shaheen, Susan; Sperling, Daniel; Wagner, Conrad (September 1999). "A Short History of Carsharing in the 90's". Journal of World Transport Policy & Practice. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Loveday, Eric (20 July 2011). "Hertz on Demand is a bit like ZipCar without membership fees". Autoblog Green. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Belson, Ken (10 September 2010). "Car Sharing: Ownership by the Hour". New York Times. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- "Zipcar Reports 2012 Third Quarter Results" (Press release). Ir.zipcar.com. 8 November 2012. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- "Wheels when you need them". The Economist. 2 September 2010. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- "The connected car". The Economist. 4 June 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Shaheen, Susan; Chan, Nelson; Bansal, Apaar; Cohen, Adam. "Shared Mobility: Definitions, Industry Developments, and Early Understanding" (PDF). Innovative Mobility Research.

- "Here Is the Future of Car Sharing, and Carmakers Should Be Terrified". www.bloomberg.com.

- Dhingra, Chhavi; Stanich, Rebecca (28 May 2013). "Car-Sharing Picking Up Speed in the Developing World". Sustainable Cities Collective. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Bartsche, Alina (9 October 2012). "How to Cut Costs Through Carsharing". CFO Insight. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Martin, Richard (22 August 2013). "Carsharing Services Will Surpass 12 Million Members Worldwide by 2020". Navigant Consulting. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Navigant Research (22 August 2013). "Navigant forecasts global carsharing services to grow to $6.2B by 2020". Green Car Congress. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Green, Caryn (16 September 2009). "Car-Sharing – Good for the Environment and the Budget". Organic Green and Natural. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- "EY debuts blockchain technology in carsharing and other news". 1 September 2017.

- Kirsten Korosec (4 July 2018). "VW plans to launch an all-electric car-sharing service next year". Techcrunch.com. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- "Car-sharing startup Getaround raises $300 million in funding led by SoftBank". Reuters.com. 21 August 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- "Moscow Residents Turn to Car-Sharing After Parking Crackdown". Themoscowtimes.com. 10 December 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- Prieto, Marc; Baltas, George; Stan, Valentina (1 July 2017). "Car sharing adoption intention in urban areas: What are the key sociodemographic drivers?". Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 101: 218–227. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2017.05.012. ISSN 0965-8564.

- News, Jelly. "Moscow : the transformation of The car-sharing capital of News". Jelly News. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Shaheen, Susan; Chan, Nelson; Bansal, Apaar; Cohen, Adam (November 2015). "Shared Mobility: Definitions, Industry Developments, and Early Understanding" (PDF). Innovative Mobility Research.

- "BMW–Daimler tie-up to bring 'largest free-floating car sharing provider'". Fleet World. 4 March 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- "Berg Insight: Carsharing service membership reached 23.8 million worldwide in 2017 | the internet of things". www.theinternetofthings.eu. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- Martin, Elliot; Shaheen, Susan (July 2016). "The Impacts of Car2go on Vehicle Ownership, Modal Shift, Vehicle Miles Traveled, and Greenhouse Gas Emissions: An Analysis of Five North American Cities". Innovative Mobility Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 2016.

- Cervero, Robert; Golub, Aaron; Nee, Brendan (2007). "City CarShare: Longer-Term Travel Demand and Car Ownership Impacts". Institute of Urban and Regional Development University of California at Berkeley. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Shaheen, Susan; Sperling, Daniel; Wagner, Conrad (Summer 1998). "Carsharing in Europe and North America: Past, Present, and Future" (PDF). Transportation Quarterly. pp. 35–52. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Lieber, Ron (22 April 2011). "Consider the Worst Case With Zipcar". The New York Times.

- Frolov, Andrey (8 August 2018). "Каршеринг "Яндекс.Драйв" договорился о поглощении стартапа мобильной заправки машин "Топливо в бак" – Транспорт на vc.ru". vc.ru.

- Shaheen, Susan A.; Cohen, Adam P.; Roberts, J. Darious (2005). "Carsharing in North America: Market Growth, Current Developments, and Future Potential". Transportation Research Record. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Toothman, Jessika (16 May 2008). "How Car Sharing Works". howstuffworks. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- "West Sussex County Council: Car clubs". West Sussex County Council. 11 December 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- "Car hire and car clubs – Driving your car". Which? Car. 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Bergen, Mark (8 August 2013). "Indian Drivers Attract Larry Summers". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carsharing. |