Capacitive sensing

In electrical engineering, capacitive sensing (sometimes capacitance sensing) is a technology, based on capacitive coupling, that can detect and measure anything that is conductive or has a dielectric different from air. Many types of sensors use capacitive sensing, including sensors to detect and measure proximity, pressure, position and displacement, force, humidity, fluid level, and acceleration. Human interface devices based on capacitive sensing, such as trackpads,[1] can replace the computer mouse. Digital audio players, mobile phones, and tablet computers use capacitive sensing touchscreens as input devices.[2] Capacitive sensors can also replace mechanical buttons.

A capacitive touchscreen typically consists of a capacitive touch sensor along with at least two complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) integrated circuit (IC) chips, an application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) controller and a digital signal processor (DSP). Capacitive sensing is commonly used for mobile multi-touch displays, popularized by Apple's iPhone in 2007.[3][4]

Design

Capacitive sensors are constructed from many different media, such as copper, indium tin oxide (ITO) and printed ink. Copper capacitive sensors can be implemented on standard FR4 PCBs as well as on flexible material. ITO allows the capacitive sensor to be up to 90% transparent (for one layer solutions, such as touch phone screens). Size and spacing of the capacitive sensor are both very important to the sensor's performance. In addition to the size of the sensor, and its spacing relative to the ground plane, the type of ground plane used is very important. Since the parasitic capacitance of the sensor is related to the electric field's (e-field) path to ground, it is important to choose a ground plane that limits the concentration of e-field lines with no conductive object present.

Designing a capacitance sensing system requires first picking the type of sensing material (FR4, Flex, ITO, etc.). One also needs to understand the environment the device will operate in, such as the full operating temperature range, what radio frequencies are present and how the user will interact with the interface.

There are two types of capacitive sensing system: mutual capacitance,[5] where the object (finger, conductive stylus) alters the mutual coupling between row and column electrodes, which are scanned sequentially;[6] and self- or absolute capacitance where the object (such as a finger) loads the sensor or increases the parasitic capacitance to ground. In both cases, the difference of a preceding absolute position from the present absolute position yields the relative motion of the object or finger during that time. The technologies are elaborated in the following section.

Surface capacitance

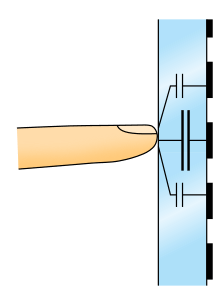

In this basic technology, only one side of the insulator is coated with conductive material. A small voltage is applied to this layer, resulting in a uniform electrostatic field.[7] When a conductor, such as a human finger, touches the uncoated surface, a capacitor is dynamically formed. Because of the sheet resistance of the surface, each corner is measured to have a different effective capacitance. The sensor's controller can determine the location of the touch indirectly from the change in the capacitance as measured from the four corners of the panel: the larger the change in capacitance, the closer the touch is to that corner. With no moving parts, it is moderately durable, but has low resolution, is prone to false signals from parasitic capacitive coupling, and needs calibration during manufacture. Therefore, it is most often used in simple applications such as industrial controls and interactive kiosks.[8]

Projected capacitance

Projected capacitive touch (PCT) technology is a capacitive technology which allows more accurate and flexible operation, by etching the conductive layer. An X-Y grid is formed either by etching one layer to form a grid pattern of electrodes, or by etching two separate, parallel layers of conductive material with perpendicular lines or tracks to form the grid; comparable to the pixel grid found in many liquid crystal displays (LCD).[9]

The greater resolution of PCT allows operation with no direct contact, such that the conducting layers can be coated with further protective insulating layers, and operate even under screen protectors, or behind weather and vandal-proof glass. Because the top layer of a PCT is glass, PCT is a more robust solution versus resistive touch technology. Depending on the implementation, an active or passive stylus can be used instead of or in addition to a finger. This is common with point of sale devices that require signature capture. Gloved fingers may not be sensed, depending on the implementation and gain settings. Conductive smudges and similar interference on the panel surface can interfere with the performance. Such conductive smudges come mostly from sticky or sweaty finger tips, especially in high humidity environments. Collected dust, which adheres to the screen because of moisture from fingertips can also be a problem.

There are two types of PCT: self capacitance, and mutual capacitance.

Mutual capacitive sensors have a capacitor at each intersection of each row and each column. A 12-by-16 array, for example, would have 192 independent capacitors. A voltage is applied to the rows or columns. Bringing a finger or conductive stylus near the surface of the sensor changes the local electric field which reduces the mutual capacitance. The capacitance change at every individual point on the grid can be measured to accurately determine the touch location by measuring the voltage in the other axis. Mutual capacitance allows multi-touch operation where multiple fingers, palms or styli can be accurately tracked at the same time.[10]

Self-capacitance sensors can have the same X-Y grid as mutual capacitance sensors, but the columns and rows operate independently. With self-capacitance, current senses the capacitive load of a finger on each column or row. This produces a stronger signal than mutual capacitance sensing, but it is unable to resolve accurately more than one finger, which results in "ghosting", or misplaced location sensing.[11]

Circuit design

Capacitance is typically measured indirectly, by using it to control the frequency of an oscillator, or to vary the level of coupling (or attenuation) of an AC signal.

The design of a simple capacitance meter is often based on a relaxation oscillator. The capacitance to be sensed forms a portion of the oscillator's RC circuit or LC circuit. Basically the technique works by charging the unknown capacitance with a known current. (The equation of state for a capacitor is i = C dv/dt. This means that the capacitance equals the current divided by the rate of change of voltage across the capacitor.) The capacitance can be calculated by measuring the charging time required to reach the threshold voltage (of the relaxation oscillator), or equivalently, by measuring the oscillator's frequency. Both of these are proportional to the RC (or LC) time constant of the oscillator circuit.

The primary source of error in capacitance measurements is stray capacitance, which if not guarded against, may fluctuate between roughly 10 pF and 10 nF. The stray capacitance can be held relatively constant by shielding the (high impedance) capacitance signal and then connecting the shield to (a low impedance) ground reference. Also, to minimize the unwanted effects of stray capacitance, it is good practice to locate the sensing electronics as near the sensor electrodes as possible.

Another measurement technique is to apply a fixed-frequency AC-voltage signal across a capacitive divider. This consists of two capacitors in series, one of a known value and the other of an unknown value. An output signal is then taken from across one of the capacitors. The value of the unknown capacitor can be found from the ratio of capacitances, which equals the ratio of the output/input signal amplitudes, as could be measured by an AC voltmeter. More accurate instruments may use a capacitance bridge configuration, similar to a Wheatstone bridge.[12] The capacitance bridge helps to compensate for any variability that may exist in the applied signal.

Comparison with other touchscreen technologies

Capacitive touchscreens are more responsive than resistive touchscreens (which react to any object since no capacitance is needed), but less accurate. However, projective capacitance improves a touchscreen's accuracy as it forms a triangulated grid around the point of touch.[13]

A standard stylus cannot be used for capacitive sensing, but special capacitive stylus, which are conductive, exist for the purpose. One can even make a capacitive stylus by wrapping conductive material, such as anti-static conductive film, around a standard stylus or rolling the film into a tube.[14] Capacitive touchscreens are more expensive to manufacture than resistive touchscreens. Some cannot be used with gloves, and can fail to sense correctly with even a small amount of water on the screen.

Mutual capacitive sensors can provide a two-dimensional image of the changes in the electric field. Using this image, a range of applications have been proposed. Authenticating users,[15][16] estimating the orientation of fingers touching the screen[17][18] and differentiating between fingers and palms[19] become possible. While capacitive sensors are used for the touchscreens of most smartphones, the capacitive image is typically not exposed to the application layer.

Power supplies with a high level of electronic noise can reduce accuracy.

Pen computing

Many stylus designs for resistive touchscreens will not register on capacitive sensors because they are not conductive. Styluses that work on capacitive touchscreens primarily designed for fingers are required to simulate the difference in dielectric offered by a human digit.[20]

References

- Larry K. Baxter (1996). Capacitive Sensors. John Wiley and Sons. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-7803-5351-0.

- Wilson, Tracy. "HowStuffWorks "Multi-touch Systems"". Retrieved August 9, 2009.

- Kent, Joel (May 2010). "Touchscreen technology basics & a new development". CMOS Emerging Technologies Conference. CMOS Emerging Technologies Research. 6: 1–13.

- Ganapati, Priya (5 March 2010). "Finger Fail: Why Most Touchscreens Miss the Point". Wired. Archived from the original on 2014-05-11. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- US Pat No 5,305,017 5,861,875

- e.g. U.S. Pat. No. 4,736,191

- cite web | url = http://www.lionprecision.com/tech-library/technotes/cap-0020-sensor-theory.html | title = Capacitive Sensor Operation and Optimization | publisher = Lionprecision.com | date = | accessdate = 2012-06-15 }}

- "Please Touch! Explore The Evolving World Of Touchscreen Technology". electronicdesign.com. Archived from the original on 2009-01-08. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- "Capacitive Touch (Touch Sensing Technologies — Part 2)". TouchAdvance.com. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

- Wagner, Armin; Kaindl, Georg (2016). "WireTouch: An Open Multi-Touch Tracker based on Mutual Capacitance Sensing". doi:10.5281/zenodo.61461. Retrieved 2020-05-23. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Self-Capacitive Touchscreens Explained (Sony Xperia Sola)

- "Basic impedance measurement techniques". Newton.ex.ac.uk. Retrieved 2012-06-15.

- "Technical Overview About Capacitive Sensing Vs. Other Touchscreen-Related Technologies". Glider Gloves. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- "How To Make A Free Capacitive Stylus". Pocketnow. 2010-02-24. Retrieved 2012-06-15.

- Holz, Christian; Buthpitiya, Senaka; Knaust, Marius (2015). "Bodyprint: Biometric User Identification on Mobile Devices Using the Capacitive Touchscreen to Scan Body Parts" (PDF). Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. doi:10.1145/2702123.2702518. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- Guo, Anhong; Xiao, Robert; Harrison, Chris (2015). "CapAuth: Identifying and Differentiating User Handprints on Commodity Capacitive Touchscreens" (PDF). Proceedings of the International Conference on Interactive Tabletops & Surfaces. doi:10.1145/2817721.2817722. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- Xiao, Robert; Schwarz, Julia; Harrison, Chris (2015). "Estimating 3D Finger Angle on Commodity Touchscreens" (PDF). Proceedings of the International Conference on Interactive Tabletops & Surfaces. doi:10.1145/2817721.2817737. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- Mayer, Sven; Le, Huy Viet; Henze, Niels (2017). "Estimating the Finger Orientation on Capacitive Touchscreens Using Convolutional Neural Networks" (PDF). Proceedings of the International Conference on Interactive Tabletops & Surfaces. doi:10.1145/3132272.3134130. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- Le, Huy Viet; Kosch, Thomas; Bader, Patrick; Mayer, Sven; Niels, Henze (2017). "PalmTouch: Using the Palm as an Additional Input Modality on Commodity Smartphones" (PDF). Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. doi:10.1145/3173574.3173934. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- J.D. Biersdorfer (2009-08-19). "Q&A: Can a Stylus Work on an iPhone?". Gadgetwise.blogs.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2012-06-15.