Digital signal processor

A digital signal processor (DSP) is a specialized microprocessor chip, with its architecture optimized for the operational needs of digital signal processing.[1][2] DSPs are fabricated on MOS integrated circuit chips.[3][4] They are widely used in audio signal processing, telecommunications, digital image processing, radar, sonar and speech recognition systems, and in common consumer electronic devices such as mobile phones, disk drives and high-definition television (HDTV) products.[3]

The goal of a DSP is usually to measure, filter or compress continuous real-world analog signals. Most general-purpose microprocessors can also execute digital signal processing algorithms successfully, but may not be able to keep up with such processing continuously in real-time. Also, dedicated DSPs usually have better power efficiency, thus they are more suitable in portable devices such as mobile phones because of power consumption constraints.[5] DSPs often use special memory architectures that are able to fetch multiple data or instructions at the same time. DSPs often also implement data compression technology, with the discrete cosine transform (DCT) in particular being a widely used compression technology in DSPs.

Overview

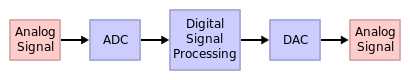

Digital signal processing algorithms typically require a large number of mathematical operations to be performed quickly and repeatedly on a series of data samples. Signals (perhaps from audio or video sensors) are constantly converted from analog to digital, manipulated digitally, and then converted back to analog form. Many DSP applications have constraints on latency; that is, for the system to work, the DSP operation must be completed within some fixed time, and deferred (or batch) processing is not viable.

Most general-purpose microprocessors and operating systems can execute DSP algorithms successfully, but are not suitable for use in portable devices such as mobile phones and PDAs because of power efficiency constraints.[5] A specialized DSP, however, will tend to provide a lower-cost solution, with better performance, lower latency, and no requirements for specialised cooling or large batteries.

Such performance improvements have led to the introduction of digital signal processing in commercial communications satellites where hundreds or even thousands of analog filters, switches, frequency converters and so on are required to receive and process the uplinked signals and ready them for downlinking, and can be replaced with specialised DSPs with significant benefits to the satellites' weight, power consumption, complexity/cost of construction, reliability and flexibility of operation. For example, the SES-12 and SES-14 satellites from operator SES launched in 2018, were both built by Airbus Defence and Space with 25% of capacity using DSP.[6]

The architecture of a DSP is optimized specifically for digital signal processing. Most also support some of the features as an applications processor or microcontroller, since signal processing is rarely the only task of a system. Some useful features for optimizing DSP algorithms are outlined below.

Architecture

Software architecture

By the standards of general-purpose processors, DSP instruction sets are often highly irregular; while traditional instruction sets are made up of more general instructions that allow them to perform a wider variety of operations, instruction sets optimized for digital signal processing contain instructions for common mathematical operations that occur frequently in DSP calculations. Both traditional and DSP-optimized instruction sets are able to compute any arbitrary operation but an operation that might require multiple ARM or x86 instructions to compute might require only one instruction in a DSP optimized instruction set.

One implication for software architecture is that hand-optimized assembly-code routines (assembly programs) are commonly packaged into libraries for re-use, instead of relying on advanced compiler technologies to handle essential algorithms. Even with modern compiler optimizations hand-optimized assembly code is more efficient and many common algorithms involved in DSP calculations are hand-written in order to take full advantage of the architectural optimizations.

Instruction sets

- multiply–accumulates (MACs, including fused multiply–add, FMA) operations

- used extensively in all kinds of matrix operations

- convolution for filtering

- dot product

- polynomial evaluation

- Fundamental DSP algorithms depend heavily on multiply–accumulate performance

- used extensively in all kinds of matrix operations

- related ISA and instructions:

- Specialized instructions for modulo addressing in ring buffers and bit-reversed addressing mode for FFT cross-referencing

- DSPs sometimes use time-stationary encoding to simplify hardware and increase coding efficiency.

- Multiple arithmetic units may require memory architectures to support several accesses per instruction cycle -- typically supporting reading 2 data values from 2 separate data buses and the next instruction (from the instruction cache, or a 3rd program memory) simultaneously.[7][8][9][10]

- Special loop controls, such as architectural support for executing a few instruction words in a very tight loop without overhead for instruction fetches or exit testing -- such as zero overhead looping[11][12] and hardware loop buffers.[13][14]

Data instructions

- Saturation arithmetic, in which operations that produce overflows will accumulate at the maximum (or minimum) values that the register can hold rather than wrapping around (maximum+1 doesn't overflow to minimum as in many general-purpose CPUs, instead it stays at maximum). Sometimes various sticky bits operation modes are available.

- Fixed-point arithmetic is often used to speed up arithmetic processing

- Single-cycle operations to increase the benefits of pipelining

Program flow

- Floating-point unit integrated directly into the datapath

- Pipelined architecture

- Highly parallel multiplier–accumulators (MAC units)

- Hardware-controlled looping, to reduce or eliminate the overhead required for looping operations

Hardware architecture

In engineering, hardware architecture refers to the identification of a system's physical components and their interrelationships. This description, often called a hardware design model, allows hardware designers to understand how their components fit into a system architecture and provides to software component designers important information needed for software development and integration. Clear definition of a hardware architecture allows the various traditional engineering disciplines (e.g., electrical and mechanical engineering) to work more effectively together to develop and manufacture new machines, devices and components.

Hardware is also an expression used within the computer engineering industry to explicitly distinguish the (electronic computer) hardware from the software that runs on it. But hardware, within the automation and software engineering disciplines, need not simply be a computer of some sort. A modern automobile runs vastly more software than the Apollo spacecraft. Also, modern aircraft cannot function without running tens of millions of computer instructions embedded and distributed throughout the aircraft and resident in both standard computer hardware and in specialized hardware components such as IC wired logic gates, analog and hybrid devices, and other digital components. The need to effectively model how separate physical components combine to form complex systems is important over a wide range of applications, including computers, personal digital assistants (PDAs), cell phones, surgical instrumentation, satellites, and submarines.

Memory architecture

DSPs are usually optimized for streaming data and use special memory architectures that are able to fetch multiple data or instructions at the same time, such as the Harvard architecture or Modified von Neumann architecture, which use separate program and data memories (sometimes even concurrent access on multiple data buses).

DSPs can sometimes rely on supporting code to know about cache hierarchies and the associated delays. This is a tradeoff that allows for better performance. In addition, extensive use of DMA is employed.

Addressing and virtual memory

DSPs frequently use multi-tasking operating systems, but have no support for virtual memory or memory protection. Operating systems that use virtual memory require more time for context switching among processes, which increases latency.

- Hardware modulo addressing

- Allows circular buffers to be implemented without having to test for wrapping

- Bit-reversed addressing, a special addressing mode

- useful for calculating FFTs

- Exclusion of a memory management unit

- Address generation unit

History

Background

Prior to the advent of stand-alone digital signal processor (DSP) chips, early digital signal processing applications were typically implemented using bit-slice chips. The AMD 2901 bit-slice chip with its family of components was a very popular choice. There were reference designs from AMD, but very often the specifics of a particular design were application specific. These bit slice architectures would sometimes include a peripheral multiplier chip. Examples of these multipliers were a series from TRW including the TDC1008 and TDC1010, some of which included an accumulator, providing the requisite multiply–accumulate (MAC) function.

Electronic signal processing was revolutionized in the 1970s by the wide adoption of the MOSFET (metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor, or MOS transistor),[15] MOS integrated circuit technology was the basis for the first single-chip microprocessors and microcontrollers in the early 1970s,[16] and then the first single-chip DSPs in the late 1970s.[3][4]

Another important development in digital signal processing was data compression. Linear predictive coding (LPC) was first developed by Fumitada Itakura of Nagoya University and Shuzo Saito of Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT) in 1966, and then further developed by Bishnu S. Atal and Manfred R. Schroeder at Bell Labs during the early-to-mid-1970s, becoming a basis for the first speech synthesizer DSP chips in the late 1970s.[17] The discrete cosine transform (DCT) was first proposed by Nasir Ahmed in the early 1970s, and has since been widely implemented in DSP chips, with many companies developing DSP chips based on DCT technology. DCTs are widely used for encoding, decoding, video coding, audio coding, multiplexing, control signals, signaling, analog-to-digital conversion, formatting luminance and color differences, and color formats such as YUV444 and YUV411. DCTs are also used for encoding operations such as motion estimation, motion compensation, inter-frame prediction, quantization, perceptual weighting, entropy encoding, variable encoding, and motion vectors, and decoding operations such as the inverse operation between different color formats (YIQ, YUV and RGB) for display purposes. DCTs are also commonly used for high-definition television (HDTV) encoder/decoder chips.[18]

Development

In 1976, Richard Wiggins proposed the Speak & Spell concept to Paul Breedlove, Larry Brantingham, and Gene Frantz at Texas Instruments' Dallas research facility. Two years later in 1978, they produced the first Speak & Spell, with the technological centerpiece being the TMS5100,[19] the industry's first digital signal processor. It also set other milestones, being the first chip to use linear predictive coding to perform speech synthesis.[20] The chip was made possible with a 7 µm PMOS fabrication process.[21]

In 1978, American Microsystems (AMI) released the S2811.[3][4] The AMI S2811 "signal processing peripheral", like many later DSPs, has a hardware multiplier that enables it to do multiply–accumulate operation in a single instruction.[22] The S2281 was the first integrated circuit chip specifically designed as a DSP, and fabricated using VMOS (V-groove MOS), a technology that had previously not been mass-produced.[4] It was designed as a microprocessor peripheral, for the Motorola 6800,[3] and it had to be initialized by the host. The S2811 was not successful in the market.

In 1979, Intel released the 2920 as an "analog signal processor".[23] It had an on-chip ADC/DAC with an internal signal processor, but it didn't have a hardware multiplier and was not successful in the market.

In 1980, the first stand-alone, complete DSPs – Nippon Electric Corporation's NEC µPD7720 and AT&T's DSP1 – were presented at the International Solid-State Circuits Conference '80. Both processors were inspired by the research in public switched telephone network (PSTN) telecommunications. The µPD7720, introduced for voiceband applications, was one of the most commercially successful early DSPs.[3]

The Altamira DX-1 was another early DSP, utilizing quad integer pipelines with delayed branches and branch prediction.

Another DSP produced by Texas Instruments (TI), the TMS32010 presented in 1983, proved to be an even bigger success. It was based on the Harvard architecture, and so had separate instruction and data memory. It already had a special instruction set, with instructions like load-and-accumulate or multiply-and-accumulate. It could work on 16-bit numbers and needed 390 ns for a multiply–add operation. TI is now the market leader in general-purpose DSPs.

About five years later, the second generation of DSPs began to spread. They had 3 memories for storing two operands simultaneously and included hardware to accelerate tight loops; they also had an addressing unit capable of loop-addressing. Some of them operated on 24-bit variables and a typical model only required about 21 ns for a MAC. Members of this generation were for example the AT&T DSP16A or the Motorola 56000.

The main improvement in the third generation was the appearance of application-specific units and instructions in the data path, or sometimes as coprocessors. These units allowed direct hardware acceleration of very specific but complex mathematical problems, like the Fourier-transform or matrix operations. Some chips, like the Motorola MC68356, even included more than one processor core to work in parallel. Other DSPs from 1995 are the TI TMS320C541 or the TMS 320C80.

The fourth generation is best characterized by the changes in the instruction set and the instruction encoding/decoding. SIMD extensions were added, and VLIW and the superscalar architecture appeared. As always, the clock-speeds have increased; a 3 ns MAC now became possible.

Modern DSPs

Modern signal processors yield greater performance; this is due in part to both technological and architectural advancements like lower design rules, fast-access two-level cache, (E)DMA circuitry and a wider bus system. Not all DSPs provide the same speed and many kinds of signal processors exist, each one of them being better suited for a specific task, ranging in price from about US$1.50 to US$300.

Texas Instruments produces the C6000 series DSPs, which have clock speeds of 1.2 GHz and implement separate instruction and data caches. They also have an 8 MiB 2nd level cache and 64 EDMA channels. The top models are capable of as many as 8000 MIPS (millions of instructions per second), use VLIW (very long instruction word), perform eight operations per clock-cycle and are compatible with a broad range of external peripherals and various buses (PCI/serial/etc). TMS320C6474 chips each have three such DSPs, and the newest generation C6000 chips support floating point as well as fixed point processing.

Freescale produces a multi-core DSP family, the MSC81xx. The MSC81xx is based on StarCore Architecture processors and the latest MSC8144 DSP combines four programmable SC3400 StarCore DSP cores. Each SC3400 StarCore DSP core has a clock speed of 1 GHz.

XMOS produces a multi-core multi-threaded line of processor well suited to DSP operations, They come in various speeds ranging from 400 to 1600 MIPS. The processors have a multi-threaded architecture that allows up to 8 real-time threads per core, meaning that a 4 core device would support up to 32 real time threads. Threads communicate between each other with buffered channels that are capable of up to 80 Mbit/s. The devices are easily programmable in C and aim at bridging the gap between conventional micro-controllers and FPGAs

CEVA, Inc. produces and licenses three distinct families of DSPs. Perhaps the best known and most widely deployed is the CEVA-TeakLite DSP family, a classic memory-based architecture, with 16-bit or 32-bit word-widths and single or dual MACs. The CEVA-X DSP family offers a combination of VLIW and SIMD architectures, with different members of the family offering dual or quad 16-bit MACs. The CEVA-XC DSP family targets Software-defined Radio (SDR) modem designs and leverages a unique combination of VLIW and Vector architectures with 32 16-bit MACs.

Analog Devices produce the SHARC-based DSP and range in performance from 66 MHz/198 MFLOPS (million floating-point operations per second) to 400 MHz/2400 MFLOPS. Some models support multiple multipliers and ALUs, SIMD instructions and audio processing-specific components and peripherals. The Blackfin family of embedded digital signal processors combine the features of a DSP with those of a general use processor. As a result, these processors can run simple operating systems like μCLinux, velocity and Nucleus RTOS while operating on real-time data.

NXP Semiconductors produce DSPs based on TriMedia VLIW technology, optimized for audio and video processing. In some products the DSP core is hidden as a fixed-function block into a SoC, but NXP also provides a range of flexible single core media processors. The TriMedia media processors support both fixed-point arithmetic as well as floating-point arithmetic, and have specific instructions to deal with complex filters and entropy coding.

CSR produces the Quatro family of SoCs that contain one or more custom Imaging DSPs optimized for processing document image data for scanner and copier applications.

Microchip Technology produces the PIC24 based dsPIC line of DSPs. Introduced in 2004, the dsPIC is designed for applications needing a true DSP as well as a true microcontroller, such as motor control and in power supplies. The dsPIC runs at up to 40MIPS, and has support for 16 bit fixed point MAC, bit reverse and modulo addressing, as well as DMA.

Most DSPs use fixed-point arithmetic, because in real world signal processing the additional range provided by floating point is not needed, and there is a large speed benefit and cost benefit due to reduced hardware complexity. Floating point DSPs may be invaluable in applications where a wide dynamic range is required. Product developers might also use floating point DSPs to reduce the cost and complexity of software development in exchange for more expensive hardware, since it is generally easier to implement algorithms in floating point.

Generally, DSPs are dedicated integrated circuits; however DSP functionality can also be produced by using field-programmable gate array chips (FPGAs).

Embedded general-purpose RISC processors are becoming increasingly DSP like in functionality. For example, the OMAP3 processors include an ARM Cortex-A8 and C6000 DSP.

In Communications a new breed of DSPs offering the fusion of both DSP functions and H/W acceleration function is making its way into the mainstream. Such Modem processors include ASOCS ModemX and CEVA's XC4000.

In May 2018, Huarui-2 designed by Nanjing Research Institute of Electronics Technology of China Electronics Technology Group passed acceptance. With a processing speed of 0.4 TFLOPS, the chip can achieve better performance than current mainstream DSP chips.[24] The design team has begun to create Huarui-3, which has a processing speed in TFLOPS level and a support for artificial intelligence.[25]

See also

References

- Dyer, S. A.; Harms, B. K. (1993). "Digital Signal Processing". In Yovits, M. C. (ed.). Advances in Computers. 37. Academic Press. pp. 104–107. doi:10.1016/S0065-2458(08)60403-9. ISBN 9780120121373.

- Liptak, B. G. (2006). Process Control and Optimization. Instrument Engineers' Handbook. 2 (4th ed.). CRC Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9780849310812.

- "1979: Single Chip Digital Signal Processor Introduced". The Silicon Engine. Computer History Museum. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Taranovich, Steve (August 27, 2012). "30 years of DSP: From a child's toy to 4G and beyond". EDN. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Ingrid Verbauwhede; Patrick Schaumont; Christian Piguet; Bart Kienhuis (2005-12-24). "Architectures and Design techniques for energy efficient embedded DSP and multimedia processing" (PDF). rijndael.ece.vt.edu. Retrieved 2017-06-13.

- Beyond Frontiers Broadgate Publications (September 2016) pp22

- "Memory and DSP Processors".

- "DSP processors: memory architectures"

- "Architecture of the Digital Signal Processor"

- "ARC XY Memory DSP Option".

- "Zero Overhead Loops".

- "ADSP-BF533 Blackfin Processor Hardware Reference". p. 4-15.

- "Understanding Advanced Processor Features Promotes Efficient Coding".

- "Techniques for Effectively Exploiting a Zero Overhead Loop Buffer".

- Grant, Duncan Andrew; Gowar, John (1989). Power MOSFETS: theory and applications. Wiley. p. 1. ISBN 9780471828679.

The metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) is the most commonly used active device in the very large-scale integration of digital integrated circuits (VLSI). During the 1970s these components revolutionized electronic signal processing, control systems and computers.

- Shirriff, Ken (30 August 2016). "The Surprising Story of the First Microprocessors". IEEE Spectrum. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Gray, Robert M. (2010). "A History of Realtime Digital Speech on Packet Networks: Part II of Linear Predictive Coding and the Internet Protocol" (PDF). Found. Trends Signal Process. 3 (4): 203–303. doi:10.1561/2000000036. ISSN 1932-8346.

- Stanković, Radomir S.; Astola, Jaakko T. (2012). "Reminiscences of the Early Work in DCT: Interview with K.R. Rao" (PDF). Reprints from the Early Days of Information Sciences. 60. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- "Speak & Spell, the First Use of a Digital Signal Processing IC for Speech Generation, 1978". IEEE Milestones. IEEE. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

- Bogdanowicz, A. (2009-10-06). "IEEE Milestones Honor Three". The Institute. IEEE. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

- Khan, Gul N.; Iniewski, Krzysztof (2017). Embedded and Networking Systems: Design, Software, and Implementation. CRC Press. p. 2. ISBN 9781351831567.

- Alberto Luis Andres. "Digital Graphic Audio Equalizer". p. 48.

- https://www.intel.com/Assets/PDF/General/35yrs.pdf#page=17

- "国产新型雷达芯片华睿2号与组网中心同时亮相-科技新闻-中国科技网首页". 科技日报. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- 王珏玢. "全国产芯片华睿2号通过"核高基"验收-新华网". Xinhua News Agency. 南京. Retrieved 2 July 2018.