Canóvanas, Puerto Rico

Canóvanas (Spanish pronunciation: [kaˈnoβanas]) is a municipality in Puerto Rico, located in the northeastern region, north of Juncos and Las Piedras; south of Loíza; east of Carolina; and west of Río Grande. Canóvanas is spread over 6 wards and Canóvanas Pueblo (the downtown area and administrative center). It is part of the San Juan-Caguas-Guaynabo Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Canóvanas Municipio de Canóvanas | |

|---|---|

Town and Municipality | |

Aerial view of PR-3 passing through Canóvanas | |

Flag | |

| Nicknames: "Pueblo Valeroso", "Ciudad de los Indios", "La Ciudad de las Carreras", "El Pueblo del Chupacabras" | |

| Anthem: "Canóvanax" | |

Map of Puerto Rico highlighting Canóvanas Municipality | |

| Coordinates: 18°22′45″N 65°54′05″W | |

| Commonwealth | |

| Founded | 1909 |

| Wards | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Lornna Soto (PNP) |

| • Senatorial dist. | 8 - Carolina |

| • Representative dist. | 37, 38 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 28.23 sq mi (73.12 km2) |

| • Land | 28 sq mi (73 km2) |

| • Water | 0.05 sq mi (.12 km2) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 47,648 |

| Demonym(s) | Canovanenses |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (AST) |

| ZIP Code | 00729 |

| Area code(s) | 787/939 |

| Major routes | |

History

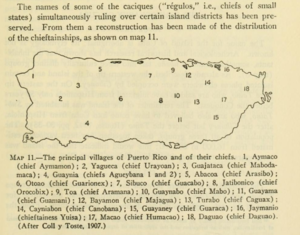

The region of what is now Canóvanas belonged to the Taíno region of Cayniabón, which stretched from the northeast coast of Puerto Rico into the central region of the island.[1] The region was led by cacique Canobaná, from which the actual name is derived, in the south half, and female Cacica Loaiza in the north (coastal portion). During the Spanish colonization, the region of Canóvanas was granted to Miguel Díaz, who turned the Taíno "yucayeque" into a ranch. It is said that Canóbana, along with Loaiza, were supporters of the Spanish regime and didn't join the Taino rebellion of 1511.[2]

Canóvanas was a barrio or subdivision of Loíza for over 400 years. In 1902, the Legislative Assembly of Puerto Rico approved a law for the consolidation of certain municipalities. As a result, both Canóvanas and Loíza were incorporated to the town of Río Grande. However, in 1905 a new law revoked the previous one, returning Canóvanas to its previous state of barrio of Loíza.[3]

In 1909, the Municipal administration of Loíza was transferred to the barrio of Canóvanas, which was more developed than the Loíza region. Also, the construction of the PR-3 facilitated the communication with Canóvanas. As a result of the transfer, land was acquired to build a new city hall, a town square, a slaughterhouse, and a cemetery. A 20-acre (8.1 ha) plot of land was purchased by Don Luis Hernaiz Veronne, a townhall Senator and local farmer. The site location was strategic, to intercept traffic from the PR-3, and from other nearby roads like the PR-185.

However, the transfer wasn't well received by the residents of the original City of Loíza, renamed "Loiza Aldea". It wasn't until a law was passed on June 30, 1969, that both towns were recognized as "clearly different population nuclei" recommending the establishment of two separate municipalities. The change was approved on 1970 by Governor Luis A. Ferré.[3]

Like other nearby towns, Canóvanas' proximity to the capital, San Juan, has allowed extraordinary urban and commercial development in the region.

Hurricane Maria

Hurricane Maria on September 20, 2017 triggered numerous landslides in Canóvanas with the significant amount of rainfall.[4][5]

.jpg) More than 400 people from Canóvanas awaiting relief

More than 400 people from Canóvanas awaiting relief.jpg) Armed petty officer guarding relief for residents of Canóvanas on Oct. 17, 2017

Armed petty officer guarding relief for residents of Canóvanas on Oct. 17, 2017

Geography

Canóvanas sits on the Northern Coastal Plain region of Puerto Rico. It is bordered by the municipalities of Loíza, Río Grande, Las Piedras, Juncos, Gurabo, and Carolina.[3] Canóvanas covers only 28 square miles (72.8 km2).[6]

Canóvanas combines flat alluvial plains in the center and north, areas with both gentle hills and rugged, deeply dissected mountainous areas made up of volcaniclastic rocks (lava flows and exposed intrusive igneous rocks) to the southeast and south. The Cuchilla de Santa Inés, a limestone hill (mogote) with an elevation of 328 feet, rises from coastal sediments on the northeast of the city near San Isidro, while the Cuchilla El Asomante lies at the south with elevations that range from 656 to 2,296 feet.

On the southeast, Canóvanas features portions of the Luquillo Mountain Range, with the Cerro El Negro being the tallest peak in the region at 2,592 feet. Other notable peaks are La Peregrina (1,903 feet) and Pitahaya (951 feet), both located at Barrio Hato Puerco.[2]

Water features

Much of the flat plains are part of the flood-prone alluvial valley of the Río Grande de Loíza and its main tributaries, the Río Canóvanas and Río Canovanillas. Floods are typical during the storm season, between June and November. Other important tributaries are the Río Herrera and Río Cubuy, as well as numerous creeks.

Barrios

Like all municipalities of Puerto Rico, Canóvanas is subdivided into barrios. The municipal buildings, central square and large Catholic church are located in a small barrio referred to as "el pueblo", near the center of the municipality.[7][8][9]

The urban center of Canóvanas is located along Road PR-3, historically the main road between San Juan and Fajardo.

Sectors

Barrios (which are like minor civil divisions)[10] in turn are further subdivided into smaller local populated place areas/units called sectores (sectors in English). The types of sectores may vary, from normally sector to urbanización to reparto to barriada to residencial, among others.[11][12][13]

Special Communities

Of the 742 places on the list of Comunidades Especiales de Puerto Rico, the following barrios, communities, sectors, or neighborhoods were in Canóvanas in 2014: Cambalache, Jardines de Palmarejo, Sector Quintas, La Central, Sector Pueblo Indio, La Central, Sector Sierra Maestra, La Central, Sector Villa Borinquén, Las 400, Las Lomas, Palma Sola, Parcelas Nuevas in San Isidro, Parcelas Viejas in San Isidro, Sector Alturas de Campo Rico, Sector Los Navarros, Sector Monte Verde, Sector Valle Hills, Sector Villa Delicias, Villa Conquistador II, Villa Hugo 1, Villa Hugo II, and Villa Sin Miedo.[14][15]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1980 | 31,880 | — | |

| 1990 | 36,816 | 15.5% | |

| 2000 | 43,335 | 17.7% | |

| 2010 | 47,648 | 10.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[16] 1980-2000[17] 2010[18] | |||

Tourism

Although Canóvanas is not particularly known for its touristic importance, there are several landmarks and places of interest to visit. The Jesús T. Piñero's house is located along the PR-3. The residence, which was built around 1931, houses a museum dedicated to the life of Jesús T. Piñero, first Puerto Rican governor of the island.[19][20]

The Hipódromo Camarero is also a tourist attraction for horserace fans of the island and the Caribbean.[21] Other places of interest are the ruins of the Canóvanas Sugar Mill, El Español Bridge, the Old Ceiba Tree, and Villarán Park.

Economy

Agriculture

The economy of Canóvanas has traditionally relied on agriculture, primarily sugarcane and coffee. There was an important sugar mill located in the PR-951 from Canóvanas to Loíza. It belonged to Loíza Sugar Company, and then to Fajardo Sugar Company. However, the mill closed in 1965.[22] In 1999, the structure was declared of historical importance by the Legislative Assembly of Puerto Rico.[23] There's also growth of minor vegetables and fruits, as well as a minor cattle and poultry industry. Most of Canóvanas flat areas are subject to occasional flooding and are used as pastures for cattle.

"Best Iguana Puerto Rico Meat" in Canóvanas is the only company in Puerto Rico certified for processing, packaging and distributing iguana meat. The iguana is an invasive species of Puerto Rico.[24]

Commerce

In recent years, Canóvanas economy has shifted to commerce and industry, supplemented by the production of fresh milk. There has also been an increase in retail businesses. There are three main shopping malls, located along the PR-3 in the Canóvanas region. These malls are the location of main stores like Wal-Mart, Marshalls, and others.

Canóvanas is sometimes referred to as "The Door to the East" due to its proximity to the San Juan Metropolitan Area, and its location en route to the northeast region of Puerto Rico. Also the expansion of Route 66 has sparked new interest in Canóvanas as an industrial and commercial sector.

Industrial

The industrial sector is growing with large international pharmaceuticals like AstraZeneca, IPR Pharmaceuticals, QBD, and other manufacturing plants in Canóvanas.

Culture

Festivals and events

Canóvanas celebrates its patron saint festival in October. The Fiestas Patronales de Nuestra Sra. del Pilar is a religious and cultural celebration that generally features parades, games, artisans, amusement rides, regional food, and live entertainment.[6][25]

Other festivals and events celebrated in Canóvanas include:

- May—Cross Festival

- December—Christmas in the Country

Sports

Although Canóvanas has no professional sports team currently active, several of its past teams have been notable. Traditionally, local sports teams bear the nickname of "Indios". The Indios de Canóvanas, of the Baloncesto Superior Nacional, won the championship two years in a row (1983-1984) and reached the finals in 1988.[26] Guard Angelo Cruz and center Ramón Ramos were two of the key players of the team during that era. However, the team disappeared during the 1990s. There have been movements to reestablish the team, but they've been unsuccessful.[27]

The Indias of Canóvanas team, from the Liga de Voleibol Superior Femenino, also won a number of championships.

Canóvanas is also the location of Hipódromo Camarero, Puerto Rico's only horse racetrack. The track, which was formerly named El Nuevo Comandante was established in 1976.[28]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 31,880 | — |

| 1990 | 36,816 | +15.5% |

| 2000 | 43,335 | +17.7% |

| 2010 | 47,648 | +10.0% |

Official population records for Canóvanas start in 1980, after the municipality was officially separated from Loíza. In 30 years, the population has increased by almost 50% according to the 2010 census.[29][30]

According to the 2010 Census, 61% of the population identifies themselves as white, and 21.6% as black. Also, 48.6% of the population identified themselves as males, and 51.4% as females. Finally, 26.7% of the population is under 18 years old. The next biggest percentage of population (21.5%) is between 35 and 49 years old.[31]

Government

All municipalities in Puerto Rico are administered by a mayor, elected every four years. The current mayor of Canóvanas is José "Chemo" Soto, of the New Progressive Party (PNP). He was elected at the 1992 general elections making him one of the longest tenured mayors currently in the island. Soto has distinguished himself for his eccentricities in clothing,[32] and for successfully using the urban legend of the Chupacabra to promote the city.[33] His daughter, Lornna, also served as a member of the Senate of Puerto Rico from 2004 to 2013.

The city belongs to the Puerto Rico Senatorial district VIII, which is represented by two Senators. In 2012, Pedro A. Rodríguez and Luis Daniel Rivera were elected as District Senators.[34] Representatives Javier Aponte Dalmau (District 38) and Ángel Bulerín (District 37) represent different regions of Canóvanas in the House of Representatives.

Symbols

Flag and coat of arms

The flag of Canóvanas features a purple background with a wide yellow band across, and the town's coat of arms in the center.

The coat of arms features a shield with the same colors (purple background and a yellow band). The colors are taken from the banner of the "Hijos y Amigos Ausentes de Canóvanas". A broken chain symbolizes the separation of Canóvanas from Loíza. The crown in the middle represents the supremacy of Cacique Canobaná. The laurels are a symbol of the 23 consecutive wins achieved by the Loíza Indians basketball team, establishing a record in Puerto Rico, also represented by the basket in the middle. The rising sun, with its sixteen rays of light, indicate the sprouting of a new municipality in Puerto Rico and the number of incumbent mayors before Canóvanas was separated from Loíza.

The coat of arms also features a white banner below with the inscription "1130 1909, Canobaná del Cayniabón, 8-16 1970". The first date, November 30, 1909, is the date of the installation of the municipal seat of Loíza in Canóvanas. The second date, August 15, 1970, is the date of the official founding of Canóvanas as a separate municipality. The names of Canobaná and Cayniabón make reference to the Taíno heritage of the region. Finally, a coronet in the form of a three-tower mural crown stands above the shield.[35]

Nicknames

Canóvanas is known by various names. It is known as the "Pueblo Valeroso" after Cacique Yuira lost her life defending the Spanish people from her own people, the Taínos. It is also known as the "City of Indians" because of its important Taíno heritage. Canóvanas is also known as the "City of Races", because of the Hipódromo Camarero, and the "Town of the Chupacabras" because of the alleged sightings of the creature, and the beliefs in it of former mayor, José Chemo Soto.[3]

Transportation

The main road to Canóvanas is the PR-3 that crosses the municipality from east to west. Distance from the capital is roughly 15 minutes.[3] Other roads that lead to Canóvanas are the #185 that enters between the Lomas and Hato Puerco wards, the #186 of the Cubuy ward, and the #957 of the Hato Puerco ward. Roads #874 and #188 enter the town from the north, the former at Torrecillas Alta from Carolina and the latter at Canóvanas Barrio from Loíza. In 2012, the PR-66, which starts in Carolina, was extended to lead directly into Canóvanas.[36]

There is also a terminal for public cars in front of the town square, as well as service provided by taxis, and independent public cars.

Canovanas is reasonably close to Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport in Carolina and to the San Juan ship docks.

There are 29 bridges in Canóvanas.[37]

Notable people

- Dayanara Martínez - Miss Mundo de Puerto Rico 2018

Books

Canóvanas, Puerto Rico The Cradle of The Indians by Greg Boudonck, Translated by Maria Ruiz O'Farrill

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canóvanas, Puerto Rico. |

References

- "Gobierno Tribal del Pueblo Jatibonicu Taíno de Puerto Rico". Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved February 3, 2013.

- "Fundación e Historia: Canóvanas". Enciclopedia de Puerto Rico. Archived from the original on 2014-01-11. Retrieved 2013-02-22.

- "Canóvanas... Pueblo Valeroso". Proyecto Salon Hogar. Archived from the original on 2012-02-22.

- "Preliminary Locations of Landslide Impacts from Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico". USGS Landslide Hazards Program. USGS. Archived from the original on 2019-03-03. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- "Preliminary Locations of Landslide Impacts from Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico" (PDF). USGS Landslide Hazards Program. USGS. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-03. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- "Canóvanas Municipality". enciclopediapr.org. Fundación Puertorriqueña de las Humanidades (FPH).

- Gwillim Law (20 May 2015). Administrative Subdivisions of Countries: A Comprehensive World Reference, 1900 through 1998. McFarland. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-4766-0447-3. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- Puerto Rico:2010:population and housing unit counts.pdf (PDF). U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-20. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- "Map of Canóvanas at the Wayback Machine" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-24. Retrieved 2018-12-29.

- "US Census Barrio-Pueblo definition". factfinder.com. US Census. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "Agencia: Oficina del Coordinador General para el Financiamiento Socioeconómico y la Autogestión (Proposed 2016 Budget)". Puerto Rico Budgets (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Rivera Quintero, Marcia (2014), El vuelo de la esperanza: Proyecto de las Comunidades Especiales Puerto Rico, 1997-2004 (first ed.), San Juan, Puerto Rico Fundación Sila M. Calderón, ISBN 978-0-9820806-1-0

- "Leyes del 2001". Lex Juris Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Rivera Quintero, Marcia (2014), El vuelo de la esperanza:Proyecto de las Comunidades Especiales Puerto Rico, 1997-2004 (Primera edición ed.), San Juan, Puerto Rico Fundación Sila M. Calderón, p. 273, ISBN 978-0-9820806-1-0

- "Comunidades Especiales de Puerto Rico" (in Spanish). 8 August 2011. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "Table 2 Population and Housing Units: 1960 to 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 24, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- Puerto Rico:2010:population and housing unit counts.pdf (PDF). U.S. Dept. of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-20. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- "Casa Museo Jesús T. Piñero". Canóvanas.PR. Archived from the original on 2014-08-22. Retrieved 2013-03-01.

- "Casa Museo Jesús T. Piñero". Canóvanas.PR. Archived from the original on 2014-08-22. Retrieved 2013-03-01.

- "Hipódromo Camarero". Canóvanas.PR. Archived from the original on 2014-08-23. Retrieved 2013-03-01.

- "Centrales Azucareras de Puerto Rico". UPRM. Archived from the original on 2009-02-14. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- "Central Azucarera - Río Grande de Loíza". Canovanas website. Archived from the original on 2014-08-22. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-07-13. Retrieved 2019-07-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Canóvanas: Events". Encyclopedia Puerto Rico. Archived from the original on 2014-08-23. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- VICOMPR (2013). "Campeonatos Baloncesto Superior Nacional". BSNPR.com. Archived from the original on 2013-03-18. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- Rosa, Jessica (February 18, 2011). "Claman por los Indios de Canóvanas". Primera Hora. Archived from the original on 2011-02-21. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- Colón, Jorge (2013). "Nuestra Historia: Hipódromo Camarero". Hipódromo Camarero. Archived from the original on 2013-03-02. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- "Población de Puerto Rico por Municipios: 1930-2000". CEEPUR. Archived from the original on 2013-03-21.

- "Población de Puerto Rico por Municipios, 2000 y 2010". Elections Puerto Rico. March 24, 2011. Archived from the original on June 3, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: Canóvanas, Puerto Rico". US Census 2010. Archived from the original on 2013-03-08.

- Rodríguez, Arys (October 29, 2011). "Chemo Soto es un "fashionista"". Primera Hora. Archived from the original on 2012-05-03. Retrieved 2013-02-25.

- Figueroa, Bárbara and Mara Resto (June 19, 2012). ""Chemo" Soto está listo para salir a capturar al chupacabras". Primera Hora. Archived from the original on 2012-09-24. Retrieved 2013-02-25.

- Elecciones Generales 2012: Escrutinio General Archived 2012-11-27 at the Wayback Machine on CEEPUR

- "Símbolos de Canóvanas". Canovanas.PR. Archived from the original on 2014-08-22. Retrieved 2013-03-02.

- Caquías, Sandra (September 14, 2012). "A recorrer casi toda la costa norte sin detenerse". El Nuevo Día. Archived from the original on 2012-11-17. Retrieved 2013-03-02.

- "Canóvanas Bridges". National Bridge Inventory Data. US Dept. of Transportation. Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.