Isla de Mona

Mona (Spanish: Isla de la Mona) is the third-largest island of the Puerto Rican archipelago, after the main island of Puerto Rico and Vieques. It is the largest of three islands in the Mona Passage, a strait between the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico, the others being Monito Island and Desecheo Island. It measures about 7 miles by 4 miles (11 km by 7 km), and lies 41 mi (66 km) west of Puerto Rico, of which it is administratively a part. It is one of two islands that make up the Isla de Mona e Islote Monito.

| Nickname: Amona | |

|---|---|

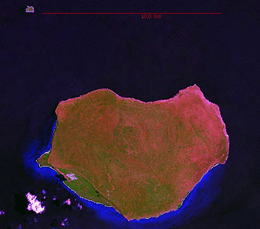

Satellite Image | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Coordinates | 18°5′12″N 67°53′22″W |

| Area | 57 km2 (22 sq mi) |

| Length | 11 km (6.8 mi) |

| Width | 7 km (4.3 mi) |

| Administration | |

United States | |

| Commonwealth | Puerto Rico |

| Municipality | Mayagüez |

| Barrio/Ward | Isla de Mona e Islote Monito |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 |

| Designated | December 17, 1993 |

| Reference no. | 93001398[1] |

| Designated | 1975 |

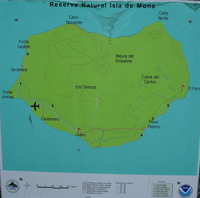

The island is managed as the Reserva Natural Isla de Mona (English: Mona Island Nature Reserve).[2] There are no native inhabitants; only rangers and biologists from Puerto Rico's Department of Natural and Environmental Resources reside on the island, to manage visitors and take part in research projects.

History

Pre-Columbian history

Mona Island is believed to have been originally settled by the Taíno since the 12th century or sooner.[3] An archeological excavation during the 1980s discovered many Pre-Columbian objects on the island that helped support historians' theories of the island's first inhabitants. Stone tools found in a rock shelter have been dated to around 3000 BC.[4] Much later the island was settled by the Taínos and remained so until the arrival of the Spanish in the 15th century.[5]

Colonial period

On November 19, 1493, during his second voyage to the New World, Christopher Columbus encountered the island now known as Puerto Rico, which the natives called Borinquen (or Borikén according to some historians), and which Columbus named San Juan Bautista (Saint John the Baptist). Within hours of setting foot in Puerto Rico, Columbus and his ships headed west to Hispaniola, where he expected to meet several crewmembers who had remained behind from his first voyage. As he left Puerto Rico, he reputedly became the first European to sight the island on September 24, 1494, which was claimed for Spain. The name Mona derives from the Taíno name Ámona, bestowed by the natives in honor of the ruling Cacique or chief of the island. However, one amateur archaeologist (Rex Cauldwell) who has studied the Mona Island/Columbus sighting for over 14 years puts this in dispute with the following logic: "Mona island is to the southwest corner of PR. Columbus is in a bay on the northwest corner. He is to sail from there straight across to the north coast of Hispaniola. Why would he sail south to where he has already been and then sail north again to Hispaniola? This is illogical. Mona Island was probably picked by armchair historians because it is the only island in the passage between Puerto Rico and Hispaniola that is drawn on most maps. It is more logical that when Columbus left the northwest coast of Puerto Rico, the small island he saw had to be Desecheo—a famous diving destination not far off the northwest coast of PR. It was never considered by armchair authors because it is small, barren, and of no interest, it is not drawn on most maps." In 1502, Fray Nicolás de Ovando was sent to Isla de la Mona to keep an eye, from a safe distance, on the native revolts occurring in Hispaniola. With a group of 2,000 Spanish settlers, Ovando was left in charge of creating a permanent settlement on the island. Due to its small size and location, the island proved inadequate to accommodate such a large settlement, and food became scarce as shipments from Hispaniola and Puerto Rico were received infrequently.

Juan Ponce de León, who accompanied Columbus on his first two voyages, became the first ruling governor of Puerto Rico.[6]

In 1515, after some wrangling, Ferdinand II was able to reclaim the island from Diego Colón, Viceroy of the Indies. By then, Isla de la Mona was an important point of trade between Spain and the rest of Latin America, as well as a rest stop for the crews of boats carrying slaves. With his possession of the island, King Ferdinand II gave the resident Taínos two options if they wished to continue living on the island: they could work by fishing, making hammocks and cultivating plants, or they could become miners and help in the mining of guano and other minerals. Realizing that mining would require intense labor, the majority of inhabitants chose to work as fishermen and farmers. By accepting this option, they also were exempted from paying imposed taxes, and were able to avoid the hard labor many other natives endured in mines. In time, natives from other neighboring islands were brought to Mona Island to assist with labor.

After the death of Ferdinand II in 1516, ownership of the island was transferred to Cardenal Cisneros. The island changed ownership again in 1520, when Francisco de Barrionuevo became the island's new landlord. By 1524, Alonso Manso, bishop of Puerto Rico, had become interested in gaining personal wealth, and he accused Barrionuevo, among others, of various crimes under the Spanish justice system of the time. Because of this situation, Barrionuevo exiled himself to one of Spain's colonies in South America, taking many Taínos along with him, and leaving the island practically deserted.

By 1522, ships from other major sea powers such as England, France, and the Netherlands began to arrive at Isla de la Mona to replenish supplies for their transatlantic voyages. The island also provided them and pirates with a refuge from which they could attack and plunder Spanish galleons.

In 1561, during an audience held in Santo Domingo, it was recommended that Isla de la Mona should become a part of that colony (which at the time occupied the eastern half of Hispaniola). The reasons offered were simply that the island was closer to Santo Domingo (presently the Dominican Republic) than to Puerto Rico, and that it had a small population which could help the colony's economy in overall agricultural production. However, the petition was turned down and the island continued to remain politically part of Puerto Rico.

In 1583, the Spanish archbishop of Puerto Rico received royal permission to bring Christianity to Mona Island. However, by this time most Taínos remaining on the island had either died or fled to mainland Puerto Rico due to repeated raiding by European (especially French) ships. From the end of the 16th century up until the mid-19th century the island was largely abandoned by the colonial authorities. It seems to have been sporadically inhabited, although records from this period are somewhat sketchy. It continued to be used as a refuge by pirates and privateers, including the notorious Captain Kidd who hid out there in 1699.[7]

The island's circumstances changed in the mid-19th century when it became the site of commercial guano mining operations. Various companies were granted licenses to extract the bat and seagull guano (a valuable fertilizer and key strategic commodity for the production of gunpowder) from the island's caves. Mining continued until 1927.[8]

Caves

Around 200 caves are on the island with thousands of native art designs and the marks and names made by early Spanish explorers.[9][10]

20th century

With the 1898 Treaty of Paris, Isla de la Mona, along with the rest of Puerto Rico, was handed by Spain to the United States. The population of Mona Isla then was 6.[11] Within two years of occupation, the Mona Island Light, left in an unfinished state since the beginning of the Spanish–American War, was completed and began operation. The lighthouse was not, as commonly believed, designed by Gustave Eiffel, but by the Spanish engineer Rafael Ravena in 1886. It was accessible by the Mona Island Tramway from the beach and remained in continuous operation until 1976 when it was replaced by a newer automated light near the centre of the island.[12]

On December 22, 1919, the island was declared an "Insular Forest of Puerto Rico", under the auspices of the U.S. Forest Law #22.

During Prohibition the island had a history of smuggling, with its geographic location making it a prime location for rum runners to smuggle rum, bourbon, and other liquor. In 1923, a stash of liquor, drugs, and perfumes, reportedly from the French islands of Martinique and Saint Martin and worth US$75,000, was found in a cave by customs officials.

In 1942, at the height of World War II, a German submarine bombarded the southern coast of the island.[13] This was one of the few incidents of that war in the Caribbean. On June 4, 1942, the oil tanker MV C.O. Stillman was sunk by the German submarine U-68 41 nautical miles (76 km) southwest of Isla de Mona.[14] From 1945 to 1955 Mona Island was leased to the U.S. Air Force as a military exercise area.

Since 1941 the island has also been used for camping and hunting goats and wild boar. In 1960 a small ranger post was established to monitor the island, operated by the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources.

In July 1972 the Environmental Quality Board of Puerto Rico, because of growing interest in the development of the islands, made a full scientific assessment of Mona and Monita using a local team of volunteer scientists. A two-volume report with maps of natural and historic features was produced.[15] It evaluated the climate, geology and mineral resources, soils, water resources, archaeology, vegetation, animals and insects, and pelagic life around the island. Shortly thereafter geotechnical and bathymetry studies were conducted by engineering firms to determine the feasibility of using Mona as a deepwater terminal for transferring oil from supertankers to smaller tankers which would continue to the mainland US; this plan was never implemented.

In 1981, the Mona Island Lighthouse was listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places as "Faro de la Isla de la Mona".

On February 15, 1985, the passenger-cargo ferry MV A Regina ran aground on a reef on the southeastern side of Mona Island. While there were no deaths nor serious injuries, 143 passengers and 72 crew members landed on Mona Island to await rescue. The wreck of the ship was removed from the reef in 1990.

In 1993, the island (perhaps all of it), as "Isla de la Mona", was listed on the National Register.[1]

Geography

Mona has an area of about 22 sq mi (57 km2) and lies 41 mi (66 km) west of the main island of Puerto Rico, 38 mi (61 km) east of the Dominican Republic, and 30 mi (48 km) southwest of Desecheo Island, another island in the Mona Passage.

Mona has been designated an ecological reserve by the Puerto Rican government and is not permanently inhabited. The US census of 2000 reports six housing units, but a population of zero.[16] The island is a ward (barrio) of the municipality of Mayagüez, together with Monito Island 3.1 mi (5 km) northwest (Isla de Mona e Islote Monito barrio). This is the largest ward of Mayagüez by area, and the only one without permanent population. The total land area of both islands in the barrio is about 21.98 square miles (56.93 km²) (Mona Island 21.924 square miles [56.783 km²] and nearby Monito Island 0.057 square miles [0.147 km²]), and it comprises 28.3 percent of the total land area of the municipality of Mayagüez. Desecheo Island, 30 mi (49 km) to the northeast, is part of Sabanetas barrio.

Mona is a mainly flat plateau surrounded by sea cliffs. It is composed of dolomite and limestone with many caves found throughout. With an arid climate and untouched by human development, many endemic species inhabit the island, such as the Mona ground iguana (Cyclura cornuta stejnegeri). Its topography, ecology, and modern history are similar to that of Navassa Island, a small limestone island located in the Jamaica Channel, between Jamaica and Haiti.

Land cover

Four types of land cover can be identified:[17]

- Cactus (4.35 square miles) (11.27 km²)

- Highland Forest (15.55 square miles) (40.28 km²)

- Central Depression Forest (0.57 square miles) (1.47 km²)

- Coastal Forest (1.46 square miles) (3.77 km²)

Beaches

Mona Island hosts a large and increasing hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) rookery with over 1,500 clutches laid annually on its beaches. The island is recognized as one of the principal sites for hawksbill nesting in the Wider Caribbean and Western Atlantic region, along with Mexico (Yucatán peninsula beaches), Barbados, Panama (Bocas del Toro), and Brazil.[18]

Critically endangered hawksbill turtle

Critically endangered hawksbill turtle Nesting hawksbill

Nesting hawksbill Playa Escalera

Playa Escalera Playa Mujeres

Playa Mujeres Playa Pájaros

Playa Pájaros Playa Sardinera

Playa Sardinera

|

Southeast beaches

|

Southwest beaches

|

Western beaches

|

The only campsites are at Playa de Pájaros and Playa Sardinera. In addition, Playa Uveros, Pájaros, Playa Mujeres and Playa Brava are important to visitors.

Mona Island today

The island presently serves as a retreat for Puerto Ricans and nature enthusiasts from all around the world, and has also become a popular destination for Puerto Rican Boy and Girl Scouts. Due to the islands' unique topography, ecology and location, Mona, Desecheo and Monito have been nicknamed "The Galápagos Islands of the Caribbean". Scientists, ecologists, and students have visited Mona Island to explore its distinct ecosystem, which includes the endemic Mona Ground Iguana. The island is also home to many cave drawings that were left behind by the island's original inhabitants. Remains of the guano mining industry can also be seen.

An FAA-certified airport that can handle small aircraft was built by the Puerto Rican government. This airport has no ICAO or IATA code. The United States Coast Guard is able to provide transportation with helicopter flights from Rafael Hernández Airport in Aguadilla, to help with medicines and first aid equipment; they also fly whenever an emergency requiring hospitalization occurs. Private and commercial planes require a special permit issued by the Puerto Rico Department of Natural Resources to use the airport's facilities.

The most common form of transportation is by private yacht, though commercial excursions are available from Cabo Rojo for small groups of up to twelve people traveling together.

Hunting is permitted in season in order to control the population growth of non-indigenous species (goats, pigs and wild cats) because they can represent a threat to various endangered species. The hunting season usually commences in December and ends in April. Camping is allowed from May through November.

In recent years, the island has become a major drop-off point especially for Dominicans, as well as Haitians and Cubans trying to reach Puerto Rico illegally. As a U.S. Commonwealth, Puerto Rico is seen by many undocumented migrants as a stepping stone to the United States. On the other hand, they are usually deported immediately.[19]

See also

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- "Reserva Natural Isla de Mona" [Mona Island Nature Reserve] (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- Powell, Eric A. (7 December 1941). "Spiritual Meeting Ground". Archaeology Magazine. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Caribbean Prehistory, US National Park Service website

- Daley, Jason. "Archaeologists Date Pre-Hispanic Puerto Rican Rock Art for the First Time". Smithsonian. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- Vicente Yañez Pinzón was appointed as the first governor of Puerto Rico but he never arrived on the island

- Hunters Flock To Puerto Rico's Remote And Rugged Mona Island, Puerto Rico Herald, June 18, 2003

- "History of the guano mining industry, Isla de Mona, Puerto Rico", Edward F. Frank

- "Cave Walls Record Early Encounters Between Old World and New". 2016-07-19. Retrieved 2016-07-20.

- Cooper, Jago; Samson, Alice V.M.; Nieves, Miguel A.; Lace, Michael J.; Caamaño-Dones, Josué; Cartwright, Caroline; Kambesis, Patricia N.; Frese, Laura del Olmo (2016-08-01). "'The Mona Chronicle': the archaeology of early religious encounter in the New World". Antiquity. 90 (352): 1054–1071. doi:10.15184/aqy.2016.103. ISSN 1745-1744.

- Joseph Prentiss Sanger; Henry Gannett; Walter Francis Willcox (1900). Informe sobre el censo de Puerto Rico, 1899, United States. War Dept. Porto Rico Census Office (in Spanish). Imprenta del gobierno. p. 164.

- Kraig Anderson: Isla de Mona Lighthouse. Retrieved on 25 August 2018.

- Battle of the Caribbean

- Esso 1946, p. 262

- Mona and Monito Islands an Assessment of their Natural and Historical Resources, assessment team directed by Frank H. Wadsworth, maps by John J. Whelan

- "US Census (2000)". Archived from the original on 2020-02-14. Retrieved 2006-06-06.

- Departamento de Recursos Naturales y Ambientales website (Puerto Rican Department of Natural and Environmental Resources; in Spanish)

- "Conservation Status of Hawksbill Turtles in the Wider Caribbean, Western Atlantic and Eastern Pacific Regions", Campbell, C.L. 2014. Conservation Status of Hawksbill Turtles in the Wider Caribbean, Western Atlantic and Eastern Pacific Regions. IAC Secretariat Pro Tempore, Virginia USA. 76p

- "Cubans using Haitian, Dominican soil to reach Puerto Rico concerns the U.S." Archived 2007-11-12 at the Wayback Machine, Dominican Today, accessed 20 April 2007

External links

- (in English) Isla de Mona, Puerto Rico - Photos and Info

- (in English) Article on Cuban refugees arriving on Mona Island

- (in Spanish) History of Mona Island

- (in English) NOAA: Tides and Currents for Isla de Mona (updated regularly)

- Welcome to Puerto Rico! Mona