Fitzgerald, Georgia

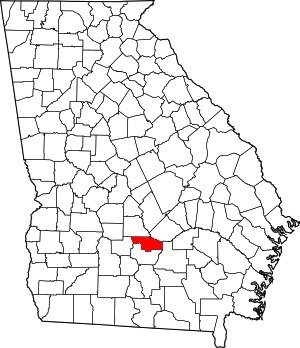

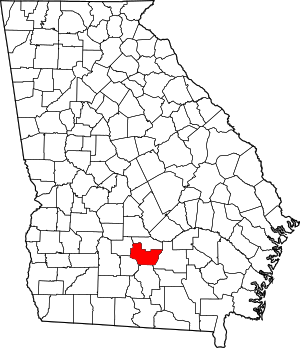

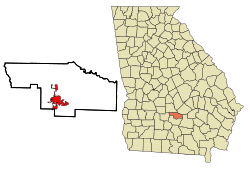

The city of Fitzgerald is the county seat of Ben Hill County in the south central portion of the U.S. state of Georgia.[6] As of the 2010 census, it had a population of 9,053.[7] It is the principal city of the Fitzgerald Micropolitan Statistical Area, which includes all of Ben Hill and Irwin counties.

Fitzgerald, Georgia | |

|---|---|

City | |

Fitzgerald City Hall | |

| Motto(s): "History, Harmony, Heritage"[1] | |

Location in Ben Hill County and the state of Georgia | |

| Coordinates: 31°42′56″N 83°15′23″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia |

| Counties | Ben Hill, Irwin |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jim Puckett |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9.10 sq mi (23.57 km2) |

| • Land | 8.95 sq mi (23.19 km2) |

| • Water | 0.15 sq mi (0.38 km2) |

| Elevation | 361 ft (110 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 9,053 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 8,662 |

| • Density | 967.61/sq mi (373.59/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 31750 |

| Area code | 229 |

| FIPS code | 13-29528[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0355809[5] |

| Website | www |

History

Fitzgerald was developed in 1895 by Philander H. Fitzgerald, an Indianapolis newspaper editor. A former drummer boy in the Union Army during the Civil War, he founded it as a community for war veterans – both from the Union and from the Confederacy.[8] The majority of the first citizens (some 2700) were Union veterans.[9] It was incorporated on December 2, 1896.[10] The town is located less than 15 miles (24 km) from the site where Confederate president Jefferson Davis was captured on May 10, 1865.

Fitzgerald was an early planned city. It was laid out as a square, with intersecting streets dividing it into four wards. Each of the wards was divided into four blocks and each block had sixteen squares.[11] The first two streets running north–south on the west side of the city were named after Confederate generals Lee and Johnston, whereas the first two on the east side were named after Union generals Grant and Sherman.[12]

After about a year, the residents planned a Thanksgiving harvest parade. Separate Union and Confederate parades were planned. But when the band struck up to play, the Confederates joined the Union veterans to march as one under the US flag.[13] This was at a time of increasing reconciliation nationwide between white soldiers of the North and South; historian David Blight notes that outstanding issues of race were pushed aside. In this period southern states had already begun to pass new constitutions that raised barriers to voter registration, following Mississippi's in 1890, and essentially disenfranchised most freedmen and many poor whites. By 1900, Fitzgerald was a sundown town, prohibiting African Americans from living there.[14]

In recent years, the unofficial, and sometimes controversial, mascot of the city has become the red junglefowl, a wild chicken native to the Indian subcontinent. In the late 1960s, a small number were released into the woods surrounding the city and have thrived to this day.[15]

Historical sites

The Ben Hill County Courthouse and Ben Hill County Jail in Fitzgerald are listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). The "Fitzgerald Commercial Historic District" was listed on the NRHP on April 28, 1992. It is generally bounded by Ocmulgee, Thomas, Magnolia and Lee streets. The "South Main-South Lee Streets Historic District" was listed on the NRHP on April 13, 1989; it is generally bounded by Magnolia Street, S. Main Street, Roanoke Drive, and S. Lee Street. The Dorminy-Massee House at 516 W. Central Avenue, the Holtzendorf Apartments at 105 W. Pine Street, and the Miles V. Wilsey House at 137 Hudson Road are also listed on the register. The Blue and Gray Museum is located near downtown in the original AB&A railroad depot built in 1908.

Geography

Fitzgerald is located in south central Georgia at 31°42′56″N 83°15′23″W (31.715432, -83.256464).[16] U.S. Route 129 passes through the center of the city, leading north to Abbeville, Hawkinsville, and eventually Macon, and south to Ocilla, Nashville, and Lakeland. U.S. Route 319 also passes through Fitzgerald, leading northeast to McRae and Dublin and southwest to Tifton.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 9.0 square miles (23.3 km2), of which 8.8 square miles (22.9 km2) is land and 0.15 square miles (0.4 km2), or 1.64%, is water.[17]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1900 | 1,817 | — | |

| 1910 | 5,795 | 218.9% | |

| 1920 | 6,870 | 18.6% | |

| 1930 | 6,412 | −6.7% | |

| 1940 | 7,388 | 15.2% | |

| 1950 | 8,130 | 10.0% | |

| 1960 | 8,781 | 8.0% | |

| 1970 | 8,187 | −6.8% | |

| 1980 | 10,187 | 24.4% | |

| 1990 | 8,612 | −15.5% | |

| 2000 | 8,758 | 1.7% | |

| 2010 | 9,053 | 3.4% | |

| Est. 2019 | 8,662 | [3] | −4.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 9,053 people living in the city. 51.2% were African American, 42.1% White, 0.3% Native American, 0.9% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 0.1% from some other race and 1.1% from two or more races. 4.3% were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

As of the census[4] of 2000, there were 8,758 people, 3,448 households, and 2,210 families living in the city. The population density was 1,208.8 people per square mile (466.4/km2). There were 3,968 housing units at an average density of 547.7 per square mile (211.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 49.27% African American, 47.27% White, 0.18% Native American, 0.31% Asian, 2.28% from other races, and 0.69% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.43% of the population.

There were 3,448 households out of which 31.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.3% were married couples living together, 23.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.9% were non-families. 31.8% of all households were made up of individuals and 14.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.47 and the average family size was 3.12.

In the city, the age distribution of the population shows 28.3% under the age of 18, 9.6% from 18 to 24, 25.7% from 25 to 44, 20.6% from 45 to 64, and 15.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 83.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 78.2 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $20,805, and the median income for a family was $26,577. Males had a median income of $26,674 versus $17,211 for females. The per capita income for the city was $12,775. About 26.7% of families and 31.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 45.8% of those under age 18 and 22.1% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture

The Dorminy-Massee House is now operated as a bed and breakfast. Built in 1915 by J. J. (Captain Jack) Dorminy for his family, this two-story, colonial-style home is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Blue and Gray Museum, located in the town's AB&A 1908 railroad depot, houses several artifacts that tell the story of the town's founding. The town also has a city government owned art gallery located in the Carnegie library on the edge of downtown.

Government and infrastructure

The U.S. Postal Service operates the Fitzgerald Post Office.

Education

The Ben Hill County School District conducts pre-school to grade twelve, and consists of one pre-school, one primary school, an elementary school, a middle school, and a high school.[19] The district has 217 full-time teachers and over 3,395 students.[20]

- Ben Hill County PreK

- Ben Hill County Primary School

- Ben Hill County Elementary School

- Ben Hill County Even Start

- Ben Hill County Middle School

- Fitzgerald High School College and Career Academy

Wiregrass Georgia Technical College – Ben Hill-Irwin Campus is located on the southern end of the county.

Media

Minor league baseball teams

Fitzgerald was home to a minor league baseball team in the Georgia State League from 1948, the league's first season of operation, through 1952. The team was called the Fitzgerald Pioneers. The club had no affiliation with any major league club during the five seasons of operation in the Georgia State League. After the 1952 season, the Fitzgerald Pioneers relocated to Sandersville and became the Sandersville Wacos, which were affiliated with the Milwaukee Braves for the 1953 season. The team ended their last season in 1956, under different affiliation.

Fitzgerald got a replacement team for the Pioneers in 1953 when the Moultrie Giants of the Georgia–Florida League moved to town. The Moultrie club was a charter member of the Georgia–Florida League when it began operations in 1946. After relocating to Fitzgerald and becoming an affiliate of the Cincinnati Redlegs, the new edition of the Fitzgerald Pioneers lasted one season (1954) saw the team name changed to the Fitzgerald Redlegs. After two years in Fitzgerald, the club returned to Moultrie. It ceased operating in 1958 under the name Brunswick Phillies.

After the Fitzgerald Redlegs left, the city was without a team for the 1955 season. The next year the Cordele club relocated to Fitzgerald after ten seasons in Cordele. They changed affiliation back to what were now called the Kansas City A's, and the Fitzgerald A's played for the 1956 season. The next year the club changed affiliation again, to the Baltimore Orioles, and the club was known as the Fitzgerald Orioles for the 1957 season. The Fitzgerald club relocated to Dublin, Georgia following the 1957 season and remained a Baltimore Orioles farm team; they played as the Dublin Orioles for the Georgia–Florida League's last year of operation. Fitzgerald has not had a minor league team in the 63 years since.

Notable people

- Morris B. Abram, president of Brandeis University and civil rights leader

- Brainard Cheney, author

- Neal Colzie, NFL defensive back

- General Raymond G. Davis, USMC, World War II hero, Korean War Medal of Honor recipient, Commander of the 3rd Marine Division in 1968–69 in Vietnam, and Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps 1971-72

- Abner Jay, blues musician

- Frances Mayes, author

- Charlie Paulk, seventh pick of 1968 NBA draft

- Joe Reliford, youngest professional baseball player

- Forrest Towns, 1936 Summer Olympics track star

- Jemea Thomas, former NFL cornerback

- Leah Robyn Masee, Miss Georgia 2007, Miss America contestant 2008

References

- "City of Fitzgerald Georgia Official Website". City of Fitzgerald Georgia Official Website. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-05-05. Retrieved 2012-05-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "website". Fitzgeraldga.org. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "Fitzgerald history". Fitzgeraldga.org. Archived from the original on 2017-09-09. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "Fitzgerald". GeorgiaGov. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- "City facts". Fitzgeraldga.org. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "Fitzgerald streets". Fitzgeraldga.org. Archived from the original on 2017-09-09. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "History". Fitzgeraldga.org. Archived from the original on 2017-09-09. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- [In the colony of Fitzgerald, in Georgia, there are very few negroes, and not one allowed to live in the city of Fitzgerald. The founders of this colony and the builders of this city are all Western people, and many of them old Union soldiers. But they met and solved the race problem by keeping the races separate and drawing, not only the color line, but the land line on the negro. "How Northern Settlers Solve the Negro Problem"] Check

|url=value (help). The Lexington Gazette. Lexington, Virginia. March 28, 1900. p. 1 – via Chronicling America. - Minor, Elliott (14 June 1998). "Town's wild jungle birds: blessing or curse?". Augusta Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2013-11-03. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Fitzgerald city, Georgia". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- Georgia Board of Education, Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- School Stats, Retrieved May 30, 2010.

Further reading

- Around Fitzgerald, Georgia, in Vintage Picture Postcards, by Milton N. Hopkins, Jr., Arcadia Publishing

- Confederates in the Attic, by Tony Horwitz, Pantheon Books

- Fitzgerald: The Early Days, by Beth Davis, privately published

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fitzgerald, Georgia. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Fitzgerald. |

- City of Fitzgerald official website

- Fitzgerald, Georgia, at City-Data.com

- Fitzgerald The Colony City historical marker

- First Baptist Church Bell historical marker

- Ozias Church Bethlehem Church historical marker