British People's Party (1939)

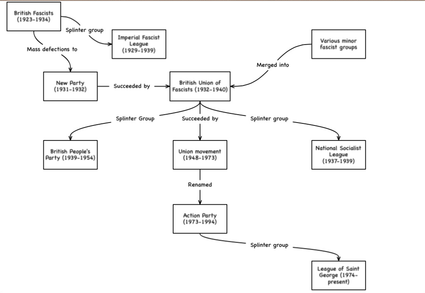

The British People's Party (BPP) was a British far-right political party founded in 1939 and led by ex-British Union of Fascists (BUF) member and Labour Party Member of Parliament John Beckett.

British People's Party | |

|---|---|

| Leader | John Beckett |

| Chairperson | Lord Tavistock |

| Founder | John Beckett, Lord Tavistock |

| Founded | 1939 |

| Dissolved | 1954 |

| Newspaper | The People's Post |

| Ideology | British Fascism Ultranationalism Social Credit Pacifism |

| |

Origins

The BPP had its roots in the journal New Pioneer, edited by John Beckett and effectively the mouthpiece of the British Council Against European Commitments, a co-ordinating body involving the National Socialist League (NSL), English Array and League of Loyalists. The main crux of this publication was opposition to war with Nazi Germany, although it also endorsed fascism and anti-Semitism.[1] The proprietor of this journal was Viscount Lymington, a strong opponent of war with Germany.[2] Others involved in its production included A. K. Chesterton and the anthropologist George Henry Lane-Fox Pitt-Rivers, whilst individual members, especially Lymington, were close to ruralist Rolf Gardiner.[3]

Policy and structure

Beckett split from his NSL ally William Joyce in 1939 after Joyce intimated to the patriotic Beckett that were war to break out between Britain and Germany he would fight for the Nazis. This, along with a feeling that Joyce's virulent anti-Semitism was hamstringing the NSL, led Beckett to link up with Lord Tavistock, the heir to the Duke of Bedford, in founding the British People's Party in 1939.[4] The new party supported an immediate end to the Second World War, and was vehemently opposed to usury, calling to mind some of the economic policies of Hilaire Belloc.[5] The group also brought in elements of Social Credit, as Lord Tavistock had been a sometime activist in the Social Credit Party.[6]

The party was controlled by an executive committee consisting of Tavistock as Chairman, Beckett as secretary and ex-Labour Party candidate Ben Greene (a noted pacifist and member of the Peace Pledge Union) as treasurer, with Viscount Lymington and former left-wing journalist John Scanlon also added.[6] Other early members of the party included Ronald Nall-Cain, 2nd Baron Brocket, Richard St. Barbe Baker, Sydney Arnold, 1st Baron Arnold, Walter Montagu Douglas Scott, 8th Duke of Buccleuch and Walter Erskine, 12th Earl of Mar.[7]

Activities

The party's activities were generally limited to meetings, the publication of a journal, The People's Post and the contesting of a single by-election in Hythe, Kent in 1939. The campaign for the 1939 Hythe by-election, in which former Labour Party member St. John Philby was the BPP candidate, was fought on an anti-war platform. Despite gaining the public support of the likes of Sir Barry Domvile, leader of The Link, the campaign was not a success and Philby was unable to retain his deposit.[6] Philby claimed that he agreed with none of the BPP's views apart from their opposition to war. He was more disposed towards the Labour Party but felt they were becoming too pro-war. In Philby's mind, as well as popularly, the BPP were seen as more of a single issue anti-war party.[8]

During the war

After the outbreak of the Second World War the BPP was involved in British Union of Fascists-led initiatives to forge closer links between the disparate groups on the far right, although in private Oswald Mosley had a low opinion of the BPP, dismissing Beckett as a "crook", Tavistock as "woolly headed" and Greene as "not very intelligent".[9] Beckett's internment under Defence Regulation 18B in 1940 saw the party go into hibernation, although it was not subject to any government ban.[2] The patronage of Lord Tavistock, who succeeded to the dukedom of Bedford in 1940, ensured that the BPP was exempted from proscription.[10] The group was briefly involved in a clandestine alliance with A.K. Chesterton's National Front After Victory in 1944, a group that also attracted the interest of J.F.C. Fuller, Henry Williamson, Jeffrey Hamm, William Morris, 1st Viscount Nuffield and Lymington (who had succeeded his father as Earl of Portsmouth in the meantime) amongst others.[11] However, the movement was scuppered when it was infiltrated by the Board of Deputies of British Jews, who fed information to Robert Vansittart, 1st Baron Vansittart, whose speech about the dangers of a revival of fascism led to a crackdown on such movements.[12]

Final years

The BPP name was heard again in 1945 when the party organised an unsuccessful petition for clemency for Beckett's former ally William Joyce, who was executed for treason.[13] Before long the BPP returned to wider activity after the war when party policy focused on monetary reform and the promotion of agriculture.[2] With the Union Movement not appearing until 1948 the BPP initially attracted some new members, including Colin Jordan, who was invited to join in 1946 and was associated with the group for a time before concentrating his efforts on the more hardline Arnold Leese.[14] The party contested the Combined English Universities by-election on 18 March 1946 but received only 239 votes.[15] The BPP officially disbanded in 1954.[2]

References

- Benewick 1969, p. 287.

- D. Boothroyd, The History of British Political Parties, London: Politico's Publishing, 2001, p. 24

- Thurlow 1987, p. 172.

- Benewick 1969, pp. 287–288.

- M. Kenny, Germany Calling, Dublin: New Island, 2004, p. 149

- Benewick 1969, p. 288.

- Dorril 2007, p. 453.

- Griffiths 1983, p. 253.

- Dorril 2007, p. 484.

- Thurlow 1987, p. 233.

- Dorril 2007, p. 547.

- Thurlow 1987, p. 241.

- G. Macklin, Very Deeply Dyed in Black, London: IB Tauris, 2007, p. 34

- Walker 1977, pp. 27–28.

- By-election results Archived 21 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Bibliography

- Benewick, Robert (1969). Political Violence & Public Order: A Study of British Fascism. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0713900859.

- Dorril, Stephen (2007). Blackshirt: Sir Oswald Mosley and British Fascism. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-025821-9.

- Griffiths, Richard (1983). Fellow Travellers of the Right: British Enthusiasts for Nazi Germany, 1933-9. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285116-1.

- Thurlow, Richard C. (1987). Fascism in Britain: A History, 1918–1985. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-13618-7.

- Walker, Martin (1977). The National Front. London: Fontana. ISBN 978-0-00-634824-5.