Boston and Skegness (UK Parliament constituency)

Boston and Skegness is a constituency (specifically, a county constituency), represented in the House of Commons of the UK Parliament. It is located in Lincolnshire, England. Like all British constituencies, Boston and Skegness elects one Member of parliament (MP) by the first-past-the-post system of election. The seat has been represented by the Conservative MP Matt Warman since the 2015 general election, and is usually considered a safe seat for the party.

| Boston and Skegness | |

|---|---|

| County constituency for the House of Commons | |

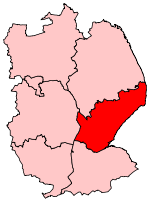

Boundary of Boston and Skegness in Lincolnshire for the 2010 general election | |

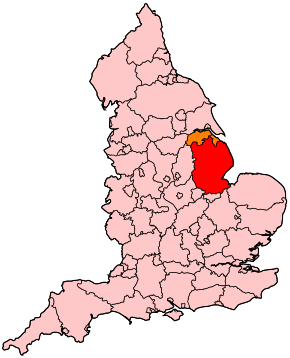

Location of Lincolnshire within England | |

| County | Lincolnshire |

| Population | 101,684 (2011 census)[1] |

| Electorate | 66,250 (2016)[2] |

| Major settlements | Boston, Hubberts Bridge, Skegness, Swineshead, Wainfleet |

| Current constituency | |

| Created | 1997 |

| Member of Parliament | Matt Warman (Conservative Party) |

| Number of members | One |

| Created from | Holland with Boston and East Lindsey |

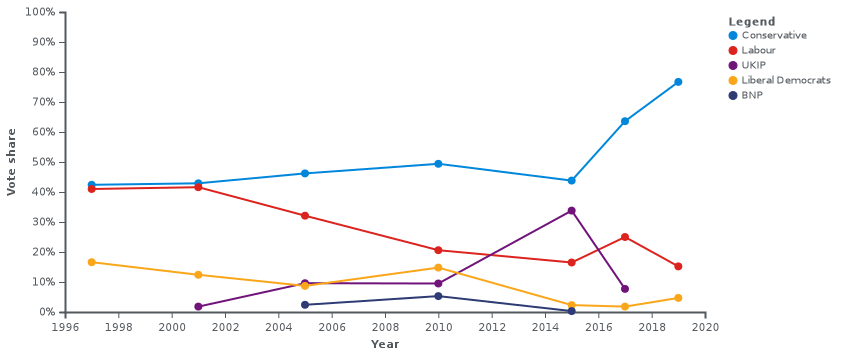

The constituency was created in 1997, from parts of the former constituencies of Holland with Boston and East Lindsey. The constituency has always elected a Conservative MP. In the 1997 and 2001 general elections, the seat was very marginal, with majorities of less than 1,000 votes for the Conservative candidate over the Labour candidate. The next two general elections, in 2005 and 2010, saw large swings towards the Conservatives. In the 2015 general election, the Eurosceptic UK Independence Party (UKIP) overtook Labour to take second place in the constituency; the party won 33.8% of the vote in the seat, which was UKIP's second-highest vote share in any constituency in that election (after Clacton). The seat had been one of UKIP's top target seats in that election, as they had also performed strongly in the constituency at the two previous general elections.

The constituency is estimated to have had the highest vote share in favour of leaving the European Union (EU) in the 2016 EU membership referendum, at 75.6%. For this reason, the leader of UKIP, Paul Nuttall, stood as the party's candidate in the seat in the 2017 general election. UKIP's vote share fell nationally that election, and they dropped to third place (behind Labour) with 7.7% of the vote, the party's third largest percentage drop in vote share. In the 2019 general election, the Conservatives increased their majority further, winning 76.7% of the vote. This was their second-highest vote share in the election (after Castle Point). The seat was also the second-safest Conservative seat in that election (measured by swing needed for the second-place party to gain the seat), after the neighbouring seat of South Holland and the Deepings.

Boundaries

In England, constituency boundaries are determined by the Boundary Commission for England, an independent body which periodically reviews the size of each constituency based on demographic data; these changes must be approved by the UK Parliament.[3][4] The constituency of Boston and Skegness was created as a county constituency,[lower-alpha 1] by a statutory instrument in 1994, as part of the Fourth Periodic Review of Westminster constituencies, and was first contested in the 1997 general election. When formed, it consisted of the Borough of Boston and the wards of Burgh le Marsh, Friskney, Frithville, Ingoldmells, St Clement's, Scarbrough, Seacroft, Sibsey, Wainfleet, and Winthorpe in the District of East Lindsey.[9] The constituency was largely created from parts of the former Holland with Boston constituency, with the remainder previously part of the former seat of East Lindsey.[10]

The constituency boundaries changed at the 2010 general election as part of the Fifth Periodic Review of Westminster constituencies, bringing in the two wards of Stickney and Croft from the neighbouring constituency of Louth and Horncastle.[11] The constituency then consisted of the Borough of Boston, and the District of East Lindsey wards of Burgh le Marsh, Croft, Frithville, Ingoldmells, St Clement's, Scarbrough, Seacroft, Sibsey, Stickney, Wainfleet and Friskney, and Winthorpe.[11] The original proposal from the Boundary Commission had been to only transfer the Croft ward, but it was then decided to also include the ward of Stickney because of its ties with the town of Boston.[12]

The Sixth Periodic Review of Westminster constituencies was carried out between 2011 and 2018, but has not been implemented because the proposed boundary changes need to be approved by the House of Commons and the House of Lords.[13][14] The review recommended that the two wards – Heckington Rural, and Kirkby la Thorpe and South Kyme – be transferred to Boston and Skegness from the constituency of Sleaford and North Hykeham.[15] This recommendation was made because Boston and Skegness was below the permitted electorate range, and Sleaford and North Hykeham was above it;[16] "electorate range" refers to the range (normally within 5% of the median British electorate) of allowed electorate size in each constituency, since legally all unprotected[lower-alpha 2] constituencies must be within this limit.[6] The proposed constituency boundaries mostly received support, though some local residents argued that the wards should remain in the same constituency as Sleaford.[17] The new constituency has an electorate of 71,989 (calculated in 2018).[18]

Boston and Skegness is bordered by the constituencies of Louth and Horncastle to the north, Sleaford and North Hykeham to the west, and South Holland and The Deepings to the south; all three of these constituencies are in the county of Lincolnshire and are all considered safe Conservative seats,[19] and have been represented by MPs from the party since the formation of the constituencies in 1997. Indeed, as of the 2019 general election, all seven Parliamentary constituencies in Lincolnshire have a Conservative MP.[20]

Constituency profile

The market town of Boston is an important administrative centre for rural Lincolnshire, and its modernised port, which brings thousands of tonnes of steel, timber and paper into the constituency, a key employer. Light industry and food processing are the other major industries in the town and surrounding villages, but elsewhere agriculture remains dominant. The resort of Skegness has recovered from a damaging dip in trade caused by pit closures in the East Midlands during the 1980s, and following regeneration through millions of pounds in EU grants, is now one of Britain’s most popular resorts, particularly among the elderly during the winter months.

Boston, Lincolnshire, is a historic town,[22] famous for the tower of St Botolph's Church, known by locals as the "Stump".[23] Skegness is a seaside town and holiday destination; the first Butlins resort opened in Skegness in 1936.[24]

The constituency has a lower level of qualifications (measured by National Vocational Qualifications) than the East Midlands average and the average for Great Britain;[25] in 2018, 19.7% of the adult population had a Higher National Diploma or degree-level qualification, compared to the British average of 39.3%.[25] The 2015 data also found that the median house price in the constituency was £125 000.[26] In 2019, the average gross weekly pay for people working full-time was £462, lower the average for Great Britain, which was £587.[25] The most common jobs are process plant and machine operatives and sales and customer service occupations. Around 40% of workers work in one of these areas, more than twice the national average.[25] The constituency also has a lower employment rate and a higher level of people on unemployment benefits than the averages for the region and the country.[25]

According to the 2011 UK Census, Boston was "home to a higher proportion of Eastern European immigrants than anywhere else in England and Wales".[27] People born in other EU countries, most of whom came from Eastern Europe after the 2004 enlargement of the European Union, made up 13% of the town's population.[23] The BBC described the town as "one of the most extreme examples in Britain of a town affected by recent EU immigration".[23] In 2015, 11.3% of people living in the constituency were born outside the UK.[26] The average age in the constituency was 32 at the time.[26]

History

Like all UK Parliament constituencies, Boston and Skegness elects one Member of Parliament (MP) using the first-past-the-post voting system.[28]

1997–2001: Marginal seat between Conservatives and Labour

The constituency was created in 1997 from parts of the former constituencies of Holland with Boston and East Lindsey. The in part predecessor area's veteran MP Richard Body, who had been MP for Holland with Boston between 1966 and 1997, held the seat at the 1997 general election with a 1.4% majority (647 votes).[29] The seat had been formed from two constituencies held by the Conservatives with large majorities, and a Conservative victory was seen as very likely. However, the election result nationally was a landslide victory for the Labour Party, and Body only narrowly remained in Parliament; the seat was the tenth most marginal Conservative-held seat at the election by percentage majority and the ninth most marginal by absolute majority (number of votes).[29][30] The academics Robert Waller and Byron Criddle attributed his victory to the Referendum Party's decision not to stand, which they did because of Body's Eurosceptic views.[10]

After retiring from Parliament, Body left the Conservatives and joined the UK Independence Party (UKIP), a party that supported British withdrawal from the European Union (EU), though he encouraged people to vote Conservative at the 2005 general election.[31] His membership later lapsed and he defected to the English Democrats, a small far-right party.[31][32]

Body's successor, the Conservative Mark Simmonds, won an even smaller majority of 1.3% over Labour in the 2001 general election (515 votes). The seat was described by Waller and Criddle as "an exceptionally tight two-way marginal".[33] The seat was the fourth most marginal Conservative seat at that election (by both percentage and absolute majority) and the most marginal Conservative seat with Labour in second place.[34][35]

2001–2010: Labour support falls, UKIP perform strongly

In the 2005 general election, Simmonds increased his majority over Labour to 14.1%. The seat had the 139th largest absolute majority and the 131st largest percentage majority out of the 198 Conservative seats.[36] Richard Horsnell, the candidate for the anti-European Union party UKIP (United Kingdom Independence Party) came third with 9.6%. This was UKIP's highest vote share in any seat in the 2005 general election, with the exception of South Staffordshire, where UKIP won 10.4% after the election was delayed due to the death of a candidate.[37][38] UKIP also performed strongly in several local council elections in Boston on the same day, winning more than 20% of the vote in some wards.[39] Overall, UKIP won 2.2% of the national vote and won an average of 2.8% in the seats they stood candidates in.[40] Meanwhile, the Liberal Democrats fell from third to fourth place with just 8.7% of the vote; this was the party's seventh-lowest vote share in any seat, and third-lowest vote share in a constituency in England, in the election.[41] Waller and Criddle said that the constituency "now looks like a fairly safe Tory [Conservative] seat", though Labour had hoped to win the seat in the election.[42]

After his re-election, Simmonds was appointed Shadow Minister for International Development in May 2005, before being moved to be a Shadow Health Minister in July 2007.[43]

In the 2010 general election, Simmonds increased his majority over Labour further, winning almost half the vote compared to Labour's 20.6%. The Liberal Democrats came third, while UKIP achieved fourth place; their candidate Christopher Pain won 9.5% of the vote. This share of the vote was similar to the result in the previous election, and was UKIP's second-highest in 2010, after the special case of Buckingham.[44][lower-alpha 3] The far-right[48][49] British National Party (BNP) also performed strongly in the constituency, winning 5.3% of the vote; since this was more than 5%, the party saved their deposit.[50]

2010–2015: Conservatives challenged by UKIP

Following the 2010 general election, Simmonds became Parliamentary Private Secretary to Caroline Spelman, the Secretary of State for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs.[51] Following the 2012 cabinet reshuffle, he became the Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs a junior role in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office.[43][52][53]

The polling company Survation analysed the results of the 2013 local elections and estimated that if UKIP were to perform equally well in a general election, then they would gain the constituency with an 11% majority. Of the ten constituencies that Survation predicted UKIP would win, Boston and Skegness had the largest predicted UKIP majority.[54] UKIP performed strongly in and near the town of Boston, which was historically a safe Conservative area; this was seen as a surprise and was attributed to voters being concerned about immigration and feeling ignored by politicians.[55] Afterwards, there was some media speculation that Nigel Farage, the leader of UKIP, might stand in the constituency at the next general election; Simmonds said he "would be delighted" if Farage did, as it would give issues in the constituency more attention.[56]

In the 2014 European Parliament election, which UKIP won ahead of Labour and the Conservatives, the Borough of Boston had the highest UKIP vote share in the country.[57][58] The party gained 52% of votes in the borough, followed by the Conservatives and then Labour.[58] This led to the constituency being seen as a top target for UKIP in the next general election.[58]

On 11 August 2014, Simmonds resigned as a minister and announced that he would step down as the Member of Parliament for Boston and Skegness at the 2015 general election.[59] Explaining his decision, he said that his salary and expenses of over £100,000 were not enough to maintain a home in London, which he said caused "intolerable" pressure in his family life.[59] This attracted some criticism, as Simmonds' salary was several times larger than the average salary in his constituency.[60] There was also media speculation that he stood down due to the threat of UKIP gaining the seat.[59]

After Simmonds announced that he would not stand at the 2015 general election, the local Conservatives decided to select their candidate using the open primary system.[61] Interviews were used to narrow down the number of applicants to four, with the winner then being chosen at a public meeting that all voters in the constituency could attend and vote in.[61][62] Several rounds of voting were used; the first two rounds, with 81 votes cast in each, both eliminated one candidate; the first candidate eliminated was Paul Bristow, who was later won the seat of Peterborough in 2019.[63] The third round saw 80 votes cast with a tie between the journalist Matt Warman and the headteacher Tim Clark.[62][63] Another vote between the two was held, which was won by Warman, then the head of technology at The Daily Telegraph.[63] Warman, who was 33 at the time of the primary, argued that UKIP's support in the area was partly due to "a real disconnect between voters and politicians"; his wife's family lived in the constituency.[64]

The seat had been one of UKIP's top target seats in that election.[65][66][67][68] The journalist and commentator Iain Dale predicted in February 2015 that UKIP would gain the seat, writing "[if] UKIP are to make a breakthrough, it might well be here";[69] overall, Dale predicted that UKIP would make five gains at the election.[70] Two opinion polls of the constituency were carried out prior to the 2015 general election. A poll in September 2014 predicted a UKIP majority of 19%,[71] while a 2015 poll forecast a narrow Conservative majority of 3%.[72] However, an internal poll conducted by UKIP (not released to the public) close to the election found a Conservative lead of seven points.[73]

On the day of the election, 8 May 2015, Warman was duly elected as the Member of Parliament; the Conservative majority shrunk to 10% with the UKIP candidate Robin Hunter-Clarke, a councillor on the Lincolnshire County Council, coming in second place. Warman won 43.8% of the vote in the seat, while Hunter-Clarke achieved 33.8%, which was UKIP's second-highest vote share in any constituency in that election (after Clacton, the only constituency the party won).[74] UKIP increased their vote share by 24.3% compared to the previous general election, while the Conservative share of the vote fell by 5.7%; this was the seventh-largest increase in vote share achieved by UKIP at the election.[75] Out of the 650 constituencies in the United Kingdom, the seat was the 126th most marginal in terms of percentage majority and 115th most marginal when measured by number of votes.[76]

2015–present: Brexit vote, becoming a safe Conservative seat

Warman's maiden speech (first speech as an MP) discussed the positive and negative effects of immigration on Boston and Skegness, saying that the pressures on public services "allowed divisive, single-issue political campaigns to flourish".[77] Warman supported remaining in the European Union in the 2016 EU membership referendum.[78] Nevertheless, the constituency is estimated to have had the highest vote share in favour of leaving the European Union (EU) in the EU referendum, at 75.6%.[79][lower-alpha 4]

On 29 April 2017, Paul Nuttall, the leader of UKIP at the time, announced that he was standing in Boston and Skegness, noting that the constituency had the highest Leave vote in the country.[84] Shortly before the election, the BBC described Boston as "Britain's unofficial Brexit capital".[85] Liberal Democrats and Labour also planned to contest the seat, with the Green Party intending to if they could find the funds for a deposit.[86] (The Green Party did stand a candidate, as did a minor party called A Blue Revolution that only had one parliamentary candidate in the election.)[87][88]

Nutall came in third place (with Labour second), winning just 7.7% of the vote; this was a decrease of 26.1% compared to 2015, and the third-largest percentage fall in UKIP vote share in that election.[89] UKIP's share of the vote fell nationally in that election, and the result was still their seventh-highest vote share of any seat.[89] The election saw UKIP achieve their worst result in the constituency since the 2001 general election. The Conservative majority increased to an all-time high in the seat, while Labour had their best result since 2005, achieving 25% of the votes cast. The Green Party and Liberal Democrats lost their deposits, mirroring the 2015 election results for both parties. Of the 46 constituencies in the East Midlands region, Boston and Skegness had the third lowest turnout at the election, at 62.7%.[90]

Based on estimates produced by Professor Chris Hanretty of Royal Holloway, University of London, Boston and Skegness had the third-highest vote share for the Brexit Party in the 2019 European Parliament election in the United Kingdom. According to Hanretty, 56.4% of votes cast in the constituency were for the new anti-EU party, which was led by Farage, behind only Castle Point and Clacton. Hanretty also estimated that the Conservatives came second in the seat, with 12.5% of the vote, followed by UKIP, who won 7.7%, their tenth strongest performance of the election. UKIP were closely followed by the Liberal Democrats and Labour, who came fourth and fifth with 7.5% and 7.4% of the vote respectively.[91]

Due to the high level of support for leaving the European Union in the constituency, the seat was discussed in 2019 as a potential target for the Brexit Party in the next general election;[92] The Brexit Party achieved high levels of support in general election polls in June and July,[93] and one estimate, by the website Electoral Calculus, suggested that the Brexit Party would gain Boston and Skegness.[94] However, the Brexit Party support decreased over time,[95][96] and in the run-up to the 2019 general election, which took place in December, some analysts thought that the large Conservative majority made victory there unlikely.[97] Farage later announced that the Brexit Party would not stand in any constituency won by the Conservatives in 2017;[98] the Brexit Party candidate was going to be Jonathan Bullock, a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) for the East Midlands constituency.[99] UKIP did not stand in the constituency; they only stood in 44 out of the 650 British seats at the election.[100] In the election, held on 12 December, the Conservatives increased their majority further, winning 76.7% of the vote.[101] This was the Conservatives' second-highest vote share in the election (after Castle Point).[101] The seat was also the fifteenth-safest seat in the election (measured by percentage majority), and the second-safest Conservative seat after neighbouring South Holland and the Deepings.[102]

Members of Parliament

Holland with Boston and East Lindsey prior to 1997

| Election | Member[103][104] | Party | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | Sir Richard Body | Conservative | |

| 2001 | Mark Simmonds | Conservative | |

| 2015 | Matt Warman | Conservative | |

Elections

Elections in the 2010s

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Matt Warman | 31,963 | 76.7 | +13.1 | |

| Labour | Ben Cook | 6,342 | 15.2 | −9.8 | |

| Liberal Democrats | Hilary Jones | 1,963 | 4.7 | +2.9 | |

| Independent | Peter Watson | 1,428 | 3.4 | N/A | |

| Majority | 25,621 | 61.5 | +22.9 | ||

| Turnout | 41,696 | 60.1 | −2.6 | ||

| Conservative hold | Swing | +11.4 | |||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Matt Warman | 27,271 | 63.6 | +19.8 | |

| Labour | Paul Kenny | 10,699 | 25.0 | +8.5 | |

| UKIP | Paul Nuttall | 3,308 | 7.7 | −26.1 | |

| Liberal Democrats | Philip Smith | 771 | 1.8 | −0.5 | |

| Green | Victoria Percival | 547 | 1.3 | −0.6 | |

| Blue Revolution | Mike Gilbert | 283 | 0.7 | N/A | |

| Majority | 16,572 | 38.6 | +28.6 | ||

| Turnout | 42,879 | 62.7 | −1.9 | ||

| Conservative hold | Swing | +5.7 | |||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Matt Warman | 18,981 | 43.8 | −5.7 | |

| UKIP | Robin Hunter-Clarke | 14,645 | 33.8 | +24.3 | |

| Labour | Paul Kenny | 7,142 | 16.5 | −4.2 | |

| Liberal Democrats | David Watts | 1,015 | 2.3 | −12.4 | |

| Green | Victoria Percival | 800 | 1.8 | N/A | |

| Independence from Europe | Chris Pain | 324 | 0.7 | N/A | |

| Independent | Peter Johnson | 170 | 0.4 | N/A | |

| The Pilgrim Party | Lyn Luxton | 143 | 0.3 | N/A | |

| BNP | Robert West | 119 | 0.3 | −5.0 | |

| Majority | 4,336 | 10.0 | −18.8 | ||

| Turnout | 43,339 | 64.6 | +3.5 | ||

| Conservative hold | Swing | −15.0 | |||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Mark Simmonds | 21,325 | 49.4 | +3.2 | |

| Labour | Paul Kenny | 8,899 | 20.6 | −11.1 | |

| Liberal Democrats | Philip Smith | 6,371 | 14.8 | +6.1 | |

| UKIP | Christopher Pain | 4,081 | 9.5 | −0.1 | |

| BNP | David Owens | 2,278 | 5.3 | +2.9 | |

| Independent | Peter Wilson | 171 | 0.4 | N/A | |

| Majority | 12,426 | 28.8 | +14.7 | ||

| Turnout | 43,125 | 61.1 | +2.2 | ||

| Conservative hold | Swing | +7.0 | |||

Elections in the 2000s

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Mark Simmonds | 19,329 | 46.2 | +3.3 | |

| Labour | Paul Kenny | 13,422 | 32.1 | −9.5 | |

| UKIP | Richard Horsnell | 4,024 | 9.6 | +7.8 | |

| Liberal Democrats | Alan Riley | 3,649 | 8.7 | −3.7 | |

| BNP | Wendy Russell | 1,025 | 2.4 | N/A | |

| Green | Marcus Petz | 420 | 1.0 | −0.3 | |

| Majority | 5,907 | 14.1 | +12.8 | ||

| Turnout | 41,869 | 58.8 | +0.5 | ||

| Conservative hold | Swing | +6.4 | |||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Mark Simmonds | 17,298 | 42.9 | +0.5 | |

| Labour | Elaine Bird | 16,783 | 41.6 | +0.6 | |

| Liberal Democrats | Duncan Moffatt | 4,994 | 12.4 | −4.2 | |

| UKIP | Cyril Wakefield | 717 | 1.8 | N/A | |

| Green | Mark Harrison | 521 | 1.3 | N/A | |

| Majority | 515 | 1.3 | −0.1 | ||

| Turnout | 40,313 | 58.4 | −10.6 | ||

| Conservative hold | Swing | −0.1 | |||

Elections in the 1990s

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Richard Body | 19,750 | 42.4 | −8.4 | |

| Labour | Philip McCauley | 19,103 | 41.0 | +12.8 | |

| Liberal Democrats | Jim Dodsworth | 7,721 | 16.6 | −4.4 | |

| Majority | 647 | 1.4 | N/A | ||

| Turnout | 46,574 | 68.9 | N/A | ||

| Conservative win (new seat) | |||||

References

Notes

- Constituencies in the United Kingdom are legally designated as either county constituencies or borough constituencies.[5] In general, county constituencies are any constituencies where more than a small proportion of the constituency is rural.[6] Legally, campaign spending limits are higher in county constituencies than in borough constituencies,[7] and the two categories of seats have different types of returning officers.[8]

- Four constituencies in the UK, all of which are island constituencies, are considered protected and exempt from this requirement.[5]

- Buckingham was at the time the seat of the Speaker of the House of Commons, John Bercow; the Speaker is seen as neutral and is traditionally not challenged by major parties.[45] The Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats did not stand in the seat in the 2010 general election, but several minor party and independent candidates, including Farage, contested the seat and the race was seen as unusually competitive.[46] Farage came third, behind Bercow and an independent candidate, John Stevens.[47]

- The results of the EU referendum were measured in counting areas, not by constituency, and the exact result for most constituencies (including Boston and Skegness)[79] is not known, but the researcher Chris Hanretty has made estimates.[80] Of the 382 counting areas, which were generally based on local authorities,[81] the Borough of Boston (which lies entirely within the constituency of Boston and Skegness), had the largest level of support for leaving the EU, at 75.6%.[82][83]

Citations

- "Boston and Skegness: Usual Resident Population, 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 1 February 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "Initial proposals for new Parliamentary constituency boundaries in the East Midlands" (PDF). Boundary Commission for England. 2016. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Stamp, Gavin (13 September 2016). "Boundary changes: Why UK's political map is being re-drawn". BBC News. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

The shake-up - drawn up by the independent Boundary [Commission] of England

- "Parliamentary constituencies". UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

Both Houses of Parliament need to agree any changes

- Boundary Commission for England 2018, p. 5.

- Boundary Commission for England 2018, p. 6.

- "2015 election campaign officially begins on Friday". BBC News. 18 December 2014. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

9p per voter in county constituencies, and 6p per voter in borough seats

- "Part A – (Acting) Returning Officer role and responsibilities" (PDF). Electoral Commission. November 2019. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

In a borough constituency contained in a district, the mayor or chairman of the local authority is the RO [returning officer]. In a county constituency, the RO is the Sheriff of the County

- "The Parliamentary Constituencies (England) Order 1995", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 1995/1626

- Waller & Criddle 1999, p. 90.

- "The Parliamentary Constituencies (England) Order 2007", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 2007/1681

- Boundary Commission for England 2007, pp. 372, 375.

- Johnston, Ron; Pattie, Charles; Rossiter, David (1 May 2019). "Boundaries in limbo: why the government cannot decide how many MPs there should be". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

the lack of progress on both that Bill and the Commissions' recommendations

- McDonald, Karl (3 January 2020). "Boundary review explained: constituency changes that could happen, and which UK parties would benefit from reform". i. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

It's been on the way since 2011, but delayed by successive Governments

- Boundary Commission for England 2018, pp. 44–45.

- Boundary Commission for England 2018, p. 44.

- Boundary Commission for England 2018, p. 45.

- "Final recommendations maps - East Midlands" (PDF). Boundary Commission for England. 2018. p. 62. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Edwards, Sharon (13 December 2019). "What are the issues for Lincolnshire voters?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

Lincolnshire is a true blue stomping ground with six of the seven seats taken by Conservative candidates in 2017 and none with a majority of less than 16,000.

- "General election 2019: Tories retake Lincoln". BBC News. 13 December 2019. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

The party now controls all seven of Lincolnshire's parliamentary constituencies

- "Boston & Skegness". BBC News. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- "The historic town of Boston in Lincolnshire". Discover Britain’s Towns. 2 September 2016. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Cook, Chris (10 May 2016). "How immigration changed Boston, Lincolnshire". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Calder, Simon (7 April 2016). "80 years of British family holidays at Butlin's". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "Labour Market Profile - Boston And Skegness Parliamentary Constituency". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 19 January 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- "Visualising your constituency". Office for National Statistics. 26 March 2015. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Pidd, Helen (11 December 2012). "Census reveals rural town of Boston has most eastern European immigrants". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "General election 2019: What is the secret behind tactical voting?". BBC News. 13 November 2019. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

The UK uses a first-past-the-post voting system, sometimes described as "winner takes all"

- Morgan 2001a, p. 80.

- Waller & Criddle 1999, p. lv.

- "Where are they now? Sir Richard Body". Total Politics. 4 March 2011. Archived from the original on 5 April 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Trilling, Daniel (15 May 2014). "Whatever happened to the English Democrats?". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

Peter Davis's election as mayor of Doncaster remains the far-right fringe party's biggest achievement

- Waller & Criddle 2002, p. 158.

- Morgan 2001b, pp. 28–29.

- Waller & Criddle 2002, p. 35.

- Mellows-Facer 2006, pp. 128–130.

- Mellows-Facer 2006, pp. 22, 47, 123, 152.

- Wheeler, Brian (17 June 2005). "The longest campaign". BBC News. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

this tragic event meant the general election would have to be postponed in Staffordshire South

- Waller & Criddle 2007, p. 200.

- Mellows-Facer 2006, p. 47.

- Mellows-Facer 2006, p. 125.

- Waller & Criddle 2007, pp. 199–200.

- "Rt Hon Mark Simmonds". UK Parliament. 2015. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

Shadow Minister (Health) Department of Health 3 July 2007 - 6 May 2010

- Rhodes, Cracknell & McGuiness 2011, p. 94.

- Wright, Katie; Willis, Ella (10 November 2019). "General election 2019: The town that won't get a choice". BBC News. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

tradition means major parties agree not to stand against the Speaker, who is considered to be politically neutral

- "A well-mannered revolution?". The Economist. 25 March 2010. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

Bercow also faces a serious challenge from UKIP's Mr Farage

- "UK: England: South East: Buckingham". BBC News. 2010. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- Pidd, Helen (2 May 2018). "As the BNP vanishes, do the forces that built it remain?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

With the far-right party’s last councillor retiring in Lancashire, its fall from grace is complete

- "Facebook bans UK far right groups and leaders". BBC News. 18 April 2019. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

Facebook has imposed a ban on a dozen far-right individuals and organisations that it says "spread hate". The ban includes the British National Party

- Rhodes, Cracknell & McGuiness 2011, pp. 94, 96.

- "Defra role for Boston MP Mark Simmonds". Boston Standard. 29 June 2010. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- "UPDATE: Foreign Office reveals Boston MP's responsibilities after reshuffle appointment". The Boston Standard. 6 September 2012. Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- "Our Ministers". Foreign and Commonwealth Office. 2012. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- "Local Election Analysis: UKIP "won" in 10 Westminster Constituencies". Survation. 12 May 2013. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- Mason, Rowena (4 May 2013). "Why did voters turn to Ukip in parts of true blue Lincolnshire?". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 8 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- Iredale, Tim (13 May 2013). "Tory MP Mark Simmonds would welcome Farage contest". BBC News. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "Farage: UKIP has 'momentum' and is targeting more victories". BBC News. 25 May 2014. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

Mr Farage has been celebrating his party's triumph in the European polls

- "UKIP's biggest support in country came in Boston - and now it is set to be key election target". Boston Standard. 28 May 2014. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

7,570 out of the 14,676 of the electorate who turned out [chose] UKIP

- Hope, Christopher (11 August 2014). "Minister quits because £120,000 salary and expenses is not enough to support his family in London". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- Hardman, Isabel (16 August 2014). "It costs £34,000 to become an MP. No wonder they expect higher pay". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

hearts will not be bleeding in his constituency, Boston and Skegness, where the average wage is £17,400

- "Details revealed of Boston and Skegness Conservative Party's 'open primary'". Boston Standard. 6 October 2014. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014.

The local association has opted for an 'open primary' method of selection which offers the public the chance to vote on applicants

- Wallace, Mark (20 October 2014). "The final four in the Boston and Skegness selection are named". ConservativeHome. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- Jaines, Daniel (25 October 2014). "Daily Telegraph journalist connects with Conservatives". Boston Standard. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

The head of technology at the Daily Telegraph has won the race to become the Boston and Skegness Conservative candidate for May 2015 in a hotly contested competition

- "OPEN PRIMARY: Daily Telegraph journalist looking to connect with voters". Boston Standard. 24 October 2014. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

Matt Warman, 33, has a strong affinity to the area, with wife Rachel's family living here

- Merill, Jamie (5 April 2015). "General Election 2015: In Boston, Ukip hope to overturn a 12,000-vote Tory majority with its immigration policies". The Independent. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

"If we don't win this seat, we are not going to win many others," admitted the law graduate [Robin Hunter-Clarke]

- Hirst, Tomas (5 May 2015). "The 14 seats most likely to go to UKIP in the May 2015 General Election". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

6. Boston and Skegness ... Verdict: This looked to be UKIP's best shot of adding to its seats, but its chances are slipping

- Hope, Christopher (4 March 2015). "Ukip already has four seats 'in the bag', says leading expert Matthew Goodwin". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

He [Goodwin] set out details of 10 seats ... which Ukip could win at May's election. They were: ... Boston and Skegness

- "General election 2015: five seats Ukip could win". Channel 4. 6 February 2015. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

"It has a strong local branch, an active councillor in Robin Hunter-Clarke (pictured) and sits in Ukip's Lincolnshire heartland," Nottingham University Politics Professor Matthew Goodwin told Channel 4 News

- Dale 2015, Lincolnshire.

- Dale 2015, The 5 UKIP Gains.

- "Boston & Skegness Constituency Poll" (PDF). Survation. 27 September 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "Boston & Skegness Poll" (PDF). Lord Ashcroft Polls. 19 February 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

Conservative 38% Labour 17% Liberal Democrat 5% UKIP 35%

- Goodwin & Milazzo 2015, p. 270.

- Hawkins et al. 2015, p. 36.

- Hawkins et al. 2015, pp. 36, 107.

- Hawkins et al. 2015, p. 109.

- Warman, Matt, MP (9 June 2015). "Matt Warman's maiden speech". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. col. 1143–1145.

- Smith, Patrick (21 July 2019). "As Brexit looms, the U.K.'s Conservative Party fights for survival". NBC News. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

While Warman, a former journalist, voted to remain in the E.U. in 2016, he is adamant that the U.K. now must leave in October

- Dempsey, Noel (6 February 2017). "EU Referendum: Constituency Results" (XLSX). House of Commons Library. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Dempsey, Noel (6 February 2017). "Brexit: votes by constituency". House of Commons Library. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

Hanretty used a model to estimate the results of the EU referendum for Parliamentary constituencies

- "How the referendum votes are counted". BBC News. 20 June 2016. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

ballots will be counted in 382 counting areas

- "Lincolnshire records UK's highest Brexit vote". BBC News. 24 June 2016. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

Boston saw the highest leave vote in the UK with almost 76% voting to exit the EU

- "Explaining Britain's immigration paradox". The Economist. 15 April 2017. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

Boston went for Brexit by 76:24, the highest margin of any local authority

- "UKIP leader Paul Nuttall to stand in Boston and Skegness". BBC News. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

he said the seat voted "overwhelmingly" for Leave in the EU referendum last year

- "Election 2017: Living in Boston - the UK's most anti-EU town". BBC News. 31 May 2017. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

Boston is Britain's unofficial Brexit capital and is being targeted by UKIP leader Paul Nuttall in the general election

- Jaines, Daniel (29 April 2017). "UKIP leader Paul Nuttall confirms he is standing for Boston and Skegness". Boston Standard. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

the Green Party has said it will field a candidate if it can pull the funds together

- "Boston & Skegness parliamentary constituency - Election 2019". BBC News. Archived from the original on 13 January 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- Heyman, Taylor (2 June 2017). "Britain's smallest parties: Meet A Blue Revolution". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

Mike Gilbert, 56, nominating officer and sole parliamentary candidate for A Blue Revolution

- Baker et al. 2019, p. 20.

- Uberoi, Baker & Cracknell 2019, p. 29.

- Hanretty, Chris (29 May 2019). "EP2019 results mapped onto Westminster constituencies". Medium. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- Wearmouth, Rachel (3 July 2019). "Back £4bn Bid To Tackle Automation Threat, Tory Think-Tank Tells Hunt And Johnson". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

Brexit Party target seats Corby, Boston and Skegness, Great Grimsby and Mansfield

- Savage, Michael (1 June 2019). "Brexit party tops Westminster election poll for first time". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

The Brexit party's support increased by two points to 26% of the vote in the latest Opinium poll

- McAllister, Richard (9 July 2019). "Shock poll predicts Brexit Party would sweep up seats in Lincolnshire in General Election". Lincolnshire Live. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

Electoral Calculus, the election prediction website run by Martin Baxter, is tipping Nigel Farage's Brexit Party to win big in the Boston and Skegness

- Rentoul, John (11 July 2019). "Brexit Party surge is fading, new poll shows". The Independent. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

BMG Research poll puts Farage's party on 14 per cent, down four since last month

- Barnes, Peter (11 December 2019). "General election poll tracker: How do the parties compare?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

The Brexit Party started the campaign at around 10% of the vote but have fallen back dramatically

- Rallings, Collin; Thrasher, Michael (3 November 2019). "Nigel Farage's Brexit Party is unlikely to win seats but can wound Boris Johnson". The Times. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

In Boston and Skegness — the only constituency to vote leave by a margin of more than three to one in 2016 — the current Tory majority is in excess of 16,500. That's a lot of voters to persuade.

- "General election 2019: Brexit Party will not stand in Tory seats". BBC News. 11 November 2019. Archived from the original on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

The party will not now stand in 317 seats won by the Tories in 2017

- Holmes, Damian (12 November 2019). "Brexit Party in u-turn on fighting Boston and Skegness seat - just a week after candidate launched campaign". Boston Standard. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- Uberoi, Baker & Cracknell, pp. 8–9, 22.

- Uberoi, Baker & Cracknell 2019, p. 10.

- Uberoi, Baker & Cracknell 2019, p. 73.

- Rayment, Leigh (25 August 2018). "The House of Commons: Constituencies beginning with "B" (part 4)". Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- "MPs representing Boston and Skegness". UK Parliament. 2017. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- Drury, Phil (14 November 2019). "Statement of Persons Nominated, Notice of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations" (PDF). Boston Borough Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "GENERAL ELECTION 2017: Candidates for Boston and Skegness confirmed". Boston Standard. 11 May 2017. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017.

- "Election Data 2015". Electoral Calculus. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- Drury, Phil (9 April 2015). "Statement of persons nominated". Boston Borough Council. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Drury, Phil (12 May 2015). "Declaration of result of poll". Boston Borough Council. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Hawkins, Keen & Nakatudde 2015, p. 90.

- "Election Data 2010". Electoral Calculus. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- "General Election candidates". Boston and Skegness General Election 2010. Boston Borough Council. 6 May 2010. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- "UK > England > East Midlands > Boston & Skegness". Election 2010. BBC. 7 May 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- "Result: Boston & Skegness". BBC News. 6 May 2005. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- "General election 2005 A-Z constituency results" (XLS). Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- Mellows-Facer 2006, p. 108.

- "Election Data 2005". Electoral Calculus. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Morgan 2001b, p. 50.

- "Election Data 2001". Electoral Calculus. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Morgan 2001a, pp. 25, 39, 53, 67.

- "Election Data 1997". Electoral Calculus. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

Works cited

- Morgan, Bryn (29 March 2001a). General Election results, 1 May 1997 (PDF) (Report). House of Commons Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morgan, Bryn (18 June 2001b). General Election results, 7 June 2001 (PDF) (Report). House of Commons Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mellows-Facer, Adam (10 March 2006). General Election 2005 (PDF) (Report). House of Commons Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rhodes, Christopher; Cracknell, Richard; McGuiness, Feargal (2 February 2011). General Election 2010 (PDF) (Report). House of Commons Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hawkins, Oliver; Keen, Richard; Nakatudde, Nambassa; Ayres, Steven; Baker, Carl; Harker, Rachael; Bolton, Paul; Johnston, Neil; Cracknell, Richard (28 July 2015). General Election 2015 (PDF) (Report). House of Commons Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baker, Carl; Hawkins, Oliver; Audickas, Lukas; Bate, Alex; Cracknell, Richard; Apostolova, Vyara; Dempsey, Noel; McInnes, Roderick; Rutherford, Tom; Uberoi, Elise (29 January 2019). General Election 2017: results and analysis (PDF) (Report). House of Commons Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Uberoi, Elise; Baker, Carl; Cracknell, Richard (19 December 2019). General Election 2019: results and analysis (PDF) (Report). House of Commons Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fifth Periodical Report (PDF) (Report). Volume 1: Report. Boundary Commission for England. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- The 2018 Review of Parliamentary Constituency Boundaries (PDF) (Report). Volume one: Report. Boundary Commission for England. September 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- Waller, Robert; Criddle, Byron (August 1999). The Almanac of British Politics (6th ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415185417.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waller, Robert; Criddle, Byron (August 2002). The Almanac of British Politics (7th ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415268349.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waller, Robert; Criddle, Byron (June 2007). The Almanac of British Politics (8th ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415378239.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dale, Iain (3 February 2015). Seat by Seat: The Political Anorak's Guide to Potential Gains and Losses in the 2015 General Election. London: Biteback Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goodwin, Matthew; Milazzo, Caitlin (November 2015). UKIP: Inside the Campaign to Redraw the Map of British Politics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198736110.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)