Bignose shark

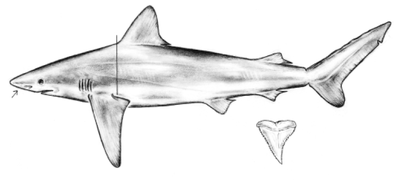

The bignose shark (Carcharhinus altimus) is a species of requiem shark, in the family Carcharhinidae. Distributed worldwide in tropical and subtropical waters, this migratory shark frequents deep waters around the edges of the continental shelf. It is typically found at depths of 90–430 m (300–1,410 ft), though at night it may move towards the surface or into shallower water. The bignose shark is plain-colored and grows to at least 2.7–2.8 m (8.9–9.2 ft) in length. It has a long, broad snout with prominent nasal skin flaps, and tall, triangular upper teeth. Its pectoral fins are long and almost straight, and there is a ridge on its back between the two dorsal fins.

| Bignose shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Carcharhinidae |

| Genus: | Carcharhinus |

| Species: | C. altimus |

| Binomial name | |

| Carcharhinus altimus (S. Springer, 1950) | |

| |

| Confirmed (dark blue) and suspected (light blue) range of the bignose shark[2] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Carcharhinus radamae Fourmanoir, 1961

| |

Hunting close to the sea floor, the bignose shark feeds on bony and cartilaginous fishes, and cephalopods. It is viviparous, meaning the embryos are sustained to term via a placental connection. Females bear litters of three to 15 pups after a 10-month gestation period. Despite its size, this shark lives too deep to pose much danger to humans. It is caught incidentally by commercial fisheries in many parts of its range; the meat, fins, skin, liver oil, and offal may be used. The International Union for Conservation of Nature presently lacks enough information to assess the global conservation status of this species. However, the various fishing pressures within its range are cause for concern given its slow reproductive rate, and it may have already declined in the northwestern Atlantic and elsewhere.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

Shark expert Stewart Springer described the bignose shark as Eulamia altima in a 1950 issue of the scientific journal American Museum Novitates. Later authors have regarded the genus Eulamia as a synonym of Carcharhinus. The specific epithet altimus is derived from the Latin altus ("deep"), and refers to the shark's deepwater habits. The type specimen is an immature female 1.3 m (4.3 ft) long, caught off Cosgrove Reef in the Florida Keys on April 2, 1947. An alternate common name for this species is Knopp's shark, originally used by Florida fishery workers since before the species was described.[3][4]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogenetic relationships of the bignose shark, based on allozyme sequences.[5] |

Phylogenetic studies published by Jack Garrick in 1982 and Leonard Compagno in 1988, based on morphology, placed the bignose shark in the "obscurus group" of Carcharhinus, centered on the dusky shark (C. obscurus) and the Galapagos shark (C. galapagensis). The group consists of large, triangular-toothed sharks with a ridge between the dorsal fins.[6][7] Gavin Naylor's 1992 study, based on allozyme sequences, upheld and further resolved this "ridge-backed" group. The bignose shark was found to be the sister species of the sandbar shark (C. plumbeus), with the two forming one of the group's two branches.[5]

Distribution and habitat

Patchy records from around the world indicate the bignose shark probably has a circumglobal distribution in tropical and subtropical waters. In the Atlantic Ocean, it occurs from Delaware Bay to Brazil, in the Mediterranean Sea, and off West Africa. In the Indian Ocean, it is known in South Africa and Madagascar, the Red Sea, India, and the Maldives. In the Pacific Ocean, it has been recorded from China to Australia, around Hawaii, and from the Gulf of California to Ecuador. It is reportedly common off Florida, the Bahamas, and the West Indies, and rare off Brazil and in the Mediterranean.[1][4]

The bignose shark is found near the edge of the continental shelf and over the upper continental slope, generally swimming close to the sea floor at depths of 90–430 m (300–1,410 ft). Young sharks may venture into water as shallow as 25 m (82 ft).[8] Night-time captures of this species from close to the surface suggest it may perform a diel vertical migration, moving from deep water upwards or toward the coast at night.[9] In the northwestern Atlantic, the bignose shark conducts a poorly documented seasonal migration, spending summer off the US East Coast and winter in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. Individual sharks have been recorded traveling distances between 1,600 and 3,200 km (1,000 and 2,000 mi).[1][4]

Description

Rather heavily built, the bignose shark has a long, broad, and blunt snout with the nostrils preceded by well-developed, triangular flaps of skin. The moderately large, circular eyes are equipped with nictitating membranes (protective third eyelids). The mouth is broadly curved and lacks obvious furrows at the corners. The upper teeth number 14–16 rows on either side and have tall, broad, triangular cusps with serrated edges; they are erect at the jaw center and become increasingly oblique towards the sides. The lower teeth number 14–15 rows on either side and have narrow, erect cusps with extremely fine serrations. The five pairs of gill slits are moderately long.[2][8]

The long and wide pectoral fins have pointed tips and nearly straight margins. The first dorsal fin originates roughly over the rear of the pectoral fin bases; it is fairly tall and falcate (sickle-shaped), with a blunt apex and a long free rear tip. The second dorsal fin is relatively large with a short free rear tip, and is positioned slightly ahead of the anal fin. A high midline ridge is present between the dorsal fins. The caudal peduncle has a crescent-shaped notch at the origin of the upper caudal fin margin. The caudal fin has a large lower lobe and a strong ventral notch near the tip of the upper lobe.[8] The dermal denticles are closely spaced but non-overlapping, such as that the skin shows between them; each is oval with three horizontal ridges leading to marginal teeth.[4] The coloration is gray to bronze above, with a faint pale stripe on the flank, and white below; sometimes there is a green sheen along the gills.[10] The tips of the fins (except for the pelvic fins) are darker; this is most obvious in young sharks. Males and females grow to at least 2.7 m (8.9 ft) and 2.8 m (9.2 ft) long respectively; this species possibly reaches 3 m (9.8 ft) in length.[4][8] The maximum weight on record is 168 kg (370 lb).[11]

Characteristic traits of the bignose shark include its prominent nasal flaps, the tall, triangular shape of its upper teeth, and the relatively anterior position of its first dorsal fin.

Characteristic traits of the bignose shark include its prominent nasal flaps, the tall, triangular shape of its upper teeth, and the relatively anterior position of its first dorsal fin. Jaws

Jaws Upper teeth

Upper teeth Lower teeth

Lower teeth

Biology and ecology

The bignose shark feeds mainly on bottom-dwelling bony fishes (including lizardfishes, croakers, flatfishes, and batfishes), cartilaginous fishes (including Squalus dogfishes, Holohalaelurus catsharks, Dasyatis stingrays, and chimaeras), and cephalopods.[8][12] In turn, juveniles may potentially fall prey to larger sharks.[10] Like other requiem sharks, this species is viviparous: when the developing embryos exhaust their supply of yolk, the depleted yolk sac is converted into a placental connection through which the mother delivers nourishment. Females bear litters of three to 15 pups, with seven being typical, following a gestation period of approximately 10 months.[12] A single litter may be sired by two or more males.[13] Birthing has been reported to occur in August and September in the Mediterranean, and in September and October off Madagascar. The newborns measure 70–90 cm (28–35 in) long. Males and females mature sexually at around 2.2 and 2.3 m (7.2 and 7.5 ft) long, respectively.[8] The average age of reproductively active individuals is 21 years.[1]

Human interactions

While large enough to perhaps be dangerous, the bignose shark seldom comes into contact with humans due to its preference for deep water.[12] This species is a bycatch of gillnet, bottom trawl, and deep-set pelagic longline fisheries (particularly those targeting tuna) in many parts of its range. It is regularly taken in Cuban waters and used to produce liver oil, shagreen, and fishmeal. Elsewhere, such as in Southeast Asia, the meat is consumed and the fins shipped to East Asia for shark fin soup. The bignose shark is not used commercially in United States, where it is listed as Prohibited Species under the 2007 Fishery Management Plan for Atlantic tunas, swordfish and sharks, or in Australia.[1]

The International Union for Conservation of Nature has listed the bignose shark as Data Deficient overall, due to inadequate population and fishery monitoring. The species is considered to be of concern, however, given it is slow-reproducing and faces widespread heavy fishing pressure. There is evidence that its numbers have recently declined in the Maldives. Furthermore, most bignose shark bycatch occurs in international waters, where a single stock may be affected by multiple fisheries. It is listed as a "highly migratory species" under the 1995 UN Agreement on the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks, but thus far this has not led to significant conservation measures. Regionally, the IUCN has assessed the bignose shark as Near Threatened in the northwestern Atlantic. Though specific data are lacking, it is suspected to have declined there because it is commonly misidentified as the sandbar shark, thus the known decline in sandbar shark numbers resulting from US longline fishing may represent a decline in bignose shark numbers, as well. This species has been assessed as Least Concern in Australian waters, where it faces no significant threats.[1]

References

- Pillans, R.; Amorim, A.; Mancini, P.; Gonzalez, M.; Anderson, C. (2009). "Carcharhinus altimus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2009: e.T161564A5452406. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2009.RLTS.T161564A5452406.en.

- Compagno, L.J.V.; Dando, M.; Fowler, S. (2005). Sharks of the World. Princeton University Press. pp. 289–290. ISBN 978-0-691-12072-0.

- Springer, S. (February 9, 1950). "A revision of North American sharks allied to the genus Carcharhinus". American Museum Novitates (1451): 1–13.

- Castro, J.I. (2011). The Sharks of North America. Oxford University Press. pp. 400–402. ISBN 978-0-19-539294-4.

- Naylor, G.J.P. (1992). "The phylogenetic relationships among requiem and hammerhead sharks: inferring phylogeny when thousands of equally most parsimonious trees result" (PDF). Cladistics. 8 (4): 295–318. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1992.tb00073.x.

- Garrick, J.A.F. (1982). Sharks of the genus Carcharhinus. NOAA Technical Report, NMFS Circ. 445: 1–194.

- Compagno, L.J.V. (1988). Sharks of the Order Carcharhiniformes. Princeton University Press. pp. 319–320. ISBN 0-691-08453-X.

- Compagno, L.J.V. (1984). Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. pp. 457–458. ISBN 92-5-101384-5.

- Anderson, R.C.; Stevens, J.D. (1996). "Review of information on diurnal vertical migration in the bignose shark (Carcharhinus altimus)". Marine and Freshwater Research. 47 (4): 605–608. doi:10.1071/mf9960605.

- Bester, C. Biological Profiles: Bignose Shark Archived 2010-06-17 at the Wayback Machine. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on June 30, 2011.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2011). "Carcharhinus altimus" in FishBase. July 2011 version.

- Hennemann, R.M. (2001). Sharks & Rays: Elasmobranch Guide of the World (second ed.). IKAN – Unterwasserarchiv. p. 132. ISBN 3-925919-33-3.

- Daly-Engel, T.S.; Grubbs, R.D.; Holland, K.N.; Toonen, R.J.; Bowen, B.W. (2006). "Assessment of multiple paternity in single litters from three species of carcharhinid sharks in Hawaii" (PDF). Environmental Biology of Fishes. 76 (2–4): 419–424. doi:10.1007/s10641-006-9008-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-26.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bignose shark. |