Battle of Sourton Down

The Battle of Sourton Down was a successful Parliamentarian ambush at Sourton Down, near Okehampton, in South West England, on 25 April 1643, during the First English Civil War. The ambush took place after a failed Parliamentarian attack on Royalist-held Launceston. After the Parliamentarians had retreated to Okehampton, Sir Ralph Hopton led a Royalist army towards Okehampton, planning to attack the town at dawn. When the Parliamentarian commander, Major-General James Chudleigh, found out, he had a dilemma; he was outnumbered, but did not want to leave his artillery for the enemy to capture. He opted to counterattack, and ambushed the 3,600-strong Royalist force on Sourton Down, laying in wait with just 108 of his own cavalry.

The ambush caught the marching army completely by surprise, and a large part of their force was immediately routed. Chudleigh called for reinforcements from his infantry in Okehampton, but they were spotted on the march there, and scattered under fire from the Royalist artillery. The Parliamentarians, still outnumbered despite their successes, chose to retreat; the Royalists, who were in complete disarray, and still did not know the size of the force they had faced, did likewise.

The defeat was humiliating for Hopton. Along with the weapons and equipment abandoned by his forces and captured by the Parliamentarians, Chudleigh captured instructions from King Charles, ordering Hopton to meet up with an army from Oxford. The discovery made the Earl of Stamford, Parliamentarian commander in Devon, overly confident. At Stratton three weeks later, Hopton won a decisive victory that secured the West Country, while Chudleigh was captured, and switched sides.

Background

When the First English Civil War began in August 1642, Cornwall was generally more supportive of the Royalist cause, while Devon and Somerset were sympathetic towards Parliament, though significant opposition existed in both areas.[2]

In July, Charles named the Marquess of Hertford commander in the West, with Sir Ralph Hopton as his deputy. They established headquarters at Wells, but threatened by a larger Parliamentarian army under the Earl of Bedford, retreated to Minehead. Hopton advised Hertford to take the infantry and artillery across the water to South Wales, while he and some 80 others joined Cornish Royalists near Truro.[3] Overall command was split between Hopton and William Ashburnham, with Sir John Berkeley in charge of logistics.[4] However, their small army consisted mostly of local Trained Bands, reluctant to serve outside Cornwall, or under non-Cornish 'foreigners'; this meant prominent roles for three locals, Sir Bevil Grenville, Sir Nicholas Slanning, and John Trevanion.[5]

Parliamentarian supporters in Devon also raised troops, initially commanded by the Earl of Pembroke. James Chudleigh, son of a Devon landowner, was authorised to levy "1000 dragoons ... in Somerset, Devon, and Cornwall"; these were used to reinforce the garrison at Barnstaple in north Devon in December 1642.[6] The Earl of Stamford was given command of Parliament's army in the West Country in January 1643, and appointed Chudleigh his deputy.[6][7]

Prelude

Victory at the Battle of Braddock Down in January 1643 secured Royalist control of Cornwall, and established Hopton as commander in the West. He wanted to attack Plymouth, but the city could easily be reinforced by sea, and the Cornish militia refused to cross the River Tamar into Devon.[8] After some minor skirmishes the two sides agreed a local truce in late February, under which Hopton retreated into Cornwall; this was greeted with incredulity by William Waller, Parliamentarian commander in the West, who argued it primarily benefited the Royalists.[9]

Anticipating the end of the truce on 22 April, Chudleigh assembled around 1,600 troops at Lifton, near Launceston, where Hopton had concentrated his army of 3,600.[10][11] The Parliamentarians attacked around 10 am the next morning,[12] but after their initial surprise, the Royalists quickly recovered, and faced by superior numbers, the Parliamentarian force withdrew to Okehampton. Hopton made little attempt to pursue him, noting that as was usual after a battle, his Cornish soldiers "grew disorderly and mutinous".[10]

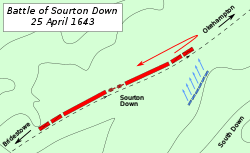

On reaching Okehampton, some of Chudleigh's units departed, leaving him 1,000 infantry, and three or four troops of dragoons.[13] This appears to have interpreted as a general retreat; Hopton later recorded "there came a friend from Okehampton, who assured us the enemy was in very great disquiet and fear."[14] Hoping to take advantage, the Royalists decided to attack, with a force of 3,000 infantry, 300 cavalry and 300 dragoons. The column was led by 300 dragoons and cavalry, then half the infantry, with their four guns in the centre. The rest of the infantry followed, with the remaining dragoons and cavalry in the rear.[14][15] They intended to stop for the night at Sourton Down, then attack Okehampton at dawn.[16]

By chance, they were spotted by a Parliamentarian quartermaster, who reported to Chudleigh around 9 pm that the enemy was only two miles (3 km) away.[16][17] Chudleigh was incensed at the failure of their scouts, he wrote that "by the intolerable neglect of our lying deputy Scout Master, we were surprised by the whole enemy body of horse and foot."[15] His problems were worsened by the fact that against his orders, the carriages and oxen needed to transport his artillery had been taken to Crediton. Since retreat would mean abandoning the guns saved at Launceston, Chudleigh decided to counterattack.[16][15]

Battle

Braddock Down Exeter Okehampton Barnstaple Launceston Roundway Down Minehead Stratton Plymouth Crediton Sourton Down |

Leaving his 1,000 infantry to follow, Chudleigh took his 108 cavalry out to Sourton Down, where he found a valley backed by hills high enough to avoid being silhouetted. He split them into six squadrons of eighteen, and they spread out to wait.[15][16] The Royalists were unaware of the threat; Hopton later admitted he and his senior officers were "carelessly entertaining themselves" at the head of the column, when the ambush was sprung around 11 pm.[14]

Chudleigh ordered his men to make as much noise as possible, to make it appear they were a far larger force.[18] The first attack was led by Captain Thomas Drake, whose squadron charged out of the darkness shouting and firing their weapons. Predominantly new levies, the Royalist dragoons broke, sweeping away the cavalry behind them, along with Hopton himself. The attack coincided with a violent thunderstorm; panicked by the noise and lights, the Cornish infantry broke, many throwing away their weapons as they ran. Chudleigh's cavalry initially overwhelmed the Royalist artillery, until Slanning was able to regain the guns, and establish a defensive position amongst ancient earthworks on the moor, reinforced with sharpened wooden stakes.[15]

Chudleigh used his cavalry to prevent the Royalists regrouping, and waited for his infantry reinforcements to come up from Okehampton before attacking Slanning. As they approached, the Royalist artillery spotted their lit matches, and opened fire, scattering the Parliamentarian infantry. Outnumbered, and having achieved his main objective, Chudleigh ordered his men to hang lit matches in gorse bushes to make it appear they were still there, and withdrew.[15] Uncertain as to the size of the attacking force, the Royalists held their position until daybreak, then retreated, first to Bridestowe, a village about two miles (3.2 km) south-west of Sourton Down, and then later that day back to Launceston.[19]

Aftermath

Do you not know, not a fortnight agoe,

How they brag'd of a Western wonder?

When a hundred and ten, slew five thousand men,

With the help of Lightning and Thunder.There Hopton was slain, again and again,

— Sir John Denham, A Western Wonder[20]

Or else my Author did lye;

With a new Thanksgiving, for who are living,

To God, and his Servant Chudleigh.

The Royalists abandoned large quantities of weapons, gunpowder, and stores, including Hopton's personal baggage; this contained letters from Charles, ordering the Cornish army to join forces with the Marquess of Hertford and Prince Maurice in Somerset. Despite their defeat, Royalist losses were relatively minor; in The Civil War in the South-West, John Barratt suggests between 20 and 100 casualties, plus a dozen prisoners.[21][lower-alpha 1] One of those captured, 15-year-old Captain Christopher Wrey, escaped, bringing some stragglers with him.[21]

Despite being absent, pamphlets published in London gave Stamford credit for the victory, a rare piece of good news for Parliament in the west.[lower-alpha 2] As was common practice on both sides, these were largely fictitious propaganda; one report suggested Hopton died after "being shot in the back in his flight."[25] In response, the Royalist poet Sir John Denham wrote a satirical piece titled A Western Wonder, mocking these reports, and praising the subsequent Royalist victory at Stratton.[25]

The capture of Hopton's instructions reportedly led to Stamford "leap(ing) out of [his] chair for joy", believing this was an opportunity for a decisive victory. He raised the largest field army he could, stripping garrisons throughout Devon, and bringing reinforcements from Somerset, to fight what he believed would be "the deciding contest of the war for the West". However, in May, he was defeated by Hopton in the Battle of Stratton, securing Royalist control of Cornwall and Devon, including Exeter, which Stamford surrendered in September.[26] Hopton advanced into Somerset, forcing Parliament to send an army under Sir William Waller, into the south-west to counter him.[27]

Notes

- Historians estimate that during the Civil War, battlefield deaths were outnumbered more than two-to-one by other deaths related to the war; due to the poor living conditions, effects of sieges and the lack of good medical care.[22][23]

- Published as 'A true relation of the wonderful victory obtained by Parliamentarian forces under the Earl of Stamford.'[24]

Citations

- Royle 2004, p. 239.

- Barratt 2005, p. 6.

- Barratt 2004, p. 78.

- Hutton 2008.

- Barratt 2005, pp. 17–18.

- Wolffe 2004.

- Hopper 2008.

- Barratt 2005, pp. 22–27.

- Royle 2004, p. 238.

- Barratt 2005, p. 28.

- Peachey 1993, p. 5.

- Peachey 1993, p. 6.

- Barratt 2005, pp. 28–29.

- Hopton 1902, p. 38.

- Barratt 2005, pp. 29–30.

- Lyon 2012, p. 87.

- Barratt 2004, p. 83.

- Andriette 1971, p. 85.

- Hopton 1902, pp. 39–41.

- Brome 1662, p. 134.

- Barratt 2005, pp. 31–32.

- Mortlock 2017.

- Gentles 2014, pp. 433–437.

- Hoare 1840, p. 41.

- Major 2016, pp. 93–95.

- Barratt 2005, pp. 32–38.

- Wroughton 2011.

References

- Andriette, Eugene (1971). Devon and Exeter in the Civil War. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-715352-56-4.

- Barratt, John (2004). Cavalier Generals: King Charles I and His Commanders in the English Civil War 1642–46. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-128-8.

- Barratt, John (2005). The Civil War in the South-West. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 1-84415-146-8.

- Brome, Alexander, ed. (1662). Rump: Or an exact Collection of the Choycest Poems and Songs relating to the Late Times. Printed for Henry Brome and Henry Marsh by Princes Armes. OCLC 921020982.

- Gentles, Ian (2014) [2007]. The English Revolution and the Wars in the Three Kingdoms, 1638–1652. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-582-06551-2.

- Hoare, Sir Richard Colt (1840). Catalogue of the Hoare Library at Stourhead, Co. Wilts. London: John Bowyer Nichols. OCLC 272594345.

- Hopper, Andrew J (2008) [2004]. "Grey, Henry, first earl of Stamford". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11537. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Hopton, Ralph (1902). Chadwyck-Healey, Charles (ed.). Bellum civile. Printed for subscribers by Harrison and Sons. OCLC 1041068269.

- Hutton, Ronald (2008) [2004]. "Hopton, Ralph, Baron Hopton". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13772. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Lyon, Rod (2012). Cornwall's Historical Wars. The Cornovia Press. ISBN 978-1-908878-05-2.

- Major, Philip, ed. (2016). Sir John Denham (1614/15–1669) Reassessed: The State's Poet. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-3156-0922-5.

- Mortlock, Stephen (1 June 2017). "Death and disease in the English Civil War". The Biomedical Scientist. Institute of Biomedical Science. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- Peachey, Stuart (1993). The Battles of Launceston and Sourton Down, 1643. Bristol: Stuart Press. ISBN 1-85804-019-1.

- Royle, Trevor (2004). Civil War: The Wars of the Three Kingdoms 1638–1660 (2006 ed.). Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-11564-1.

- Wolffe, Mary (2004). "Chudleigh, James". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5382. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Wroughton, John (17 February 2011). "The Civil War in the West". BBC History. Retrieved 26 August 2019.