Battle of Powick Bridge

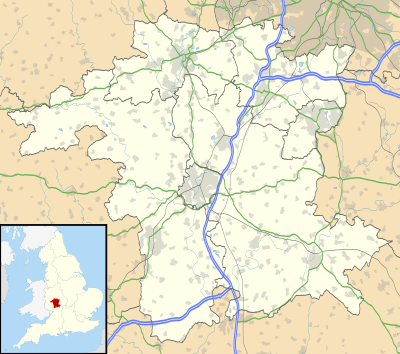

The Battle of Powick Bridge was a minor skirmish fought on 23 September 1642 just south of Worcester, England, during the First English Civil War. It was the first engagement between elements of the principal field armies of the Royalists and Parliamentarians. Sir John Byron was escorting a Royalist convoy of valuables from Oxford to King Charles's army in Shrewsbury, and took refuge in Worcester, where he requested assistance. The Royalists sent reinforcements under Prince Rupert, while the Parliamentarians sent a detachment, commanded by Colonel John Brown, to try to capture the convoy. Both forces consisted of around 1,000 mounted troops, a mix of cavalry and dragoons.

The Parliamentarians approached the city from the south on the afternoon of 23 September. Their route took them up narrow lanes, and straight into Rupert's force, which was resting in a field. The noise of the Parliamentarian cavalry approaching alerted Rupert, who quickly drew up his men. The Royalist dragoons gave their cavalry time to prepare, firing at point-blank range as the Parliamentarians emerged into the field. Rupert's cavalry then charged and broke most of the Parliamentarian cavalry, though one troop stood its ground and returned fire. Ultimately, all of the Parliamentarians were routed.

Brown covered his cavalry's escape by making a stand with his dragoons at Powick Bridge; Rupert gave chase as far as Powick village, but the Parliamentarian cavalry fled 15 miles (24 km) further, with their flight causing panic among part of the main Parliamentarian field army. The Royalists abandoned Worcester, leaving safely with their valuable convoy. The Parliamentarian army arrived in the city the next day, and remained for four weeks before covering the Royalist move towards London, which led to the Battle of Edgehill.

Background

Build-up of the First English Civil War

In 1642 the tension between the English Parliament and King Charles, which had been building throughout his reign, escalated sharply after the King had attempted to arrest five Members of Parliament, who he accused of treason. Having failed, Charles fled London with his family; many historians believe these events made civil war inevitable.[1] In preparation for the likely conflict, both sides began preparing for war; attempting to recruit the existing militia and new men into their armies. Parliament passed the Militia Ordinance in March 1642 without Royal assent, granting themselves control of the militia. In response, Charles granted commissions of array to his commanders, a medieval device for levying soldiers which had not been used since the mid-sixteenth century.[2]

Despite the manoeuvrings between the King and Parliament, there remained an illusion that the two sides were still governing the country together. This illusion ended when Charles moved to York in mid-March, fearing that he would be captured if he remained in the south of England. The first open conflict between the two sides occurred at Kingston-upon-Hull, where a large arsenal housed arms and equipment collected for the earlier Bishops' Wars.[3] During the first Siege of Hull, Charles was twice refused entrance into the city, in April and July, by the Parliamentarian governor.[4] Charles was successful in raising men to the Royalist cause in the north of England, the East Midlands and Wales, but without control of a significant arsenal, he lacked the means to arm them. In contrast, Parliament drew troops from the south-east of England, had plentiful arms, and controlled the navy.[5]

On 22 August, Charles took a decisive step by raising his royal standard in Nottingham, effectively declaring war on Parliament.[6] The two sides continued to recruit; Parliament positioned its main field army, commanded by the Earl of Essex, in between the King and London, in Northampton.[7] Charles was heavily outnumbered at this stage; he fielded between a quarter and half as many men as Essex, and those he did have were not so well equipped.[8][9] Despite this, Essex did not press his advantage: possibly because his orders allowed him to present the King with a petition to peacefully submit to Parliament, as an alternative to military action.[10] Although there had been small-scale fighting, particularly in northern and south-western England, the two field armies did not begin to significantly manoeuvre against each other until mid-September.[11] On 13 September, Charles moved his army west through Derby and Stafford towards Shrewsbury, where he hoped to be able to assemble the Royalist regiments being raised in the Wales and the north- and south-west of England.[12]

Sir John Byron's convoy

Sir John Byron was a staunch supporter of King Charles, and raised what was probably the first Royalist cavalry regiment of the war. In August, he occupied Oxford with that 160-strong regiment until it was forced to withdraw on 10 September in the face of a larger Parliamentarian force. He left with a large convoy of gold and silver plate which had been donated by Oxford University to help fund the King's war preparations. Heading towards the Royalist forces in Shrewsbury, Byron became aware of the proximity of the Parliamentarian army, and chose to seek refuge in nearby Worcester on 16 September.[13]

Worcester was a large town on the River Severn, which was surrounded by medieval city walls, though they were in poor condition. The city gates were still opened in the morning and closed each evening, but they were rotten and according to the historian J. W. Willis-Bund, they were in such poor condition that "they would hardly shut, and if they were actually closed there was neither lock or bolt to secure them".[14] The city was predominantly sympathetic towards the Parliamentarians,[15] and aware that he would not be able to hold the city against either the internal or external threats, Byron sent a messenger requesting assistance.[14]

Prelude

The Parliamentarians did not react to the movement of the Royalist army until 19 September, as they sought intelligence on the King's destination, and then moved on a parallel path, through Coventry and towards Worcester. This would again position Parliament's army between the Royalists and London, while the city was also surrounded by agricultural land which could support Essex's army.[16] As they reached Stratford-upon-Avon, roughly 24 miles (39 km) from Worcester,[17] Essex received intelligence of the Royalist convoy. He was convinced by one of his cavalry colonels, John Brown, to send a detachment to the city to try and capture the valuables being transported.[18]

Brown led a detachment of around 1,000 mounted troops which reached the area just south of Worcester on 22 September, and secured a bridge across the north–south flowing Severn. According to a report written by or for Nathaniel Fiennes, another of the Parliamentarian officers present, Colonel Edwin Sandys then argued that they should continue towards Worcester, to prevent the convoy from escaping. They continued on to Powick, just south of the east–west flowing River Teme, around two miles (3.2 km) south of Worcester. There they spent the night and most of the following day,[18] ostensibly guarding the route they expected Byron to attempt to escape along.[19]

Unknown to the Parliamentarians, who did not send out scouts, nor post a lookout in the church tower,[19] Byron had been reinforced by Prince Rupert, the Royalist General of Horse, who also had around 1,000 mounted troops. Rupert's men were just north of the Teme, guarding the southern approach to the city. The modern historian Peter Gaunt suggests that Rupert was probably aware of the presence of the Parliamentarian detachment in the area,[20] but he allowed his men to rest in a field known as Wick Field (or Brickfield Meadow), and many removed their armour.[21]

Opposing forces

There were two major categories of mounted troops, often referred to simply as "horse", during the First English Civil War. Dragoons were mounted infantry, armed with muskets, who were typically used as skirmishers or as part of advanced guards due to their mobility. They rode into battle, but dismounted to fight. The cavalry remained mounted to fight, generally on larger horses than dragoons. Most were harquebusiers, who were armoured with a helmet and plate armour on their torso, and carried a sword, two pistols and a carbine.[22] Rupert's force was split roughly evenly between dragoons and cavalry, while the Parliamentarians had ten troops of cavalry and five companies of dragoons.[19]

Cavalry tactics in the two forces differed quite significantly. The Parliamentarians used tactics which originated in the army of the Dutch Republic which had been the preeminent force at the start of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), and with whom many English cavalry officers had first experienced battle. In both attack and defence, Parliamentarian cavalry relied on their firepower. When they were on the offensive, one rank at a time moved forwards to fire at their opponents, while in defence the cavalry remained stationary and fired into the enemy charge, hoping to break their opponents and then counter-charge.[23] In contrast, Rupert's cavalry fought using a modified version of tactics used by Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden. In shallower files to allow a greater frontage, the Royalist cavalry attacked on the charge,[lower-alpha 1] only using their firearms when they were already in amongst their opponents, and often relied on their swords instead.[24]

Battle

At around 4 pm, Brown and Sandys ordered an advance towards the city.[25] Brooks suggests that they had received intelligence that Byron was preparing to leave Worcester.[19] Sandys led a small group of troops ahead, across the narrow bridge and along a country lane which allowed no more than three riders abreast. The noise of the Parliamentarian horsemen alerted Rupert to their approach, and he rapidly prepared his men for battle as best as he could. He lined the hedges with the dismounted dragoons while the cavalry were drawn up into open order in the meadow.[26] When Sandys and his cavalry troop emerged into the field, they were faced with point-blank carbine fire from the dragoons, allowing the Royalist cavalry time to prepare.[19][26]

The Parliamentarians attempted to regroup in order to return fire, but they were charged by Rupert's cavalry. At some point in the initial assault, Sandys was mortally wounded. With no support from their dragoons, which were stuck behind the cavalry in the narrow country lanes, Sandys' troop were routed.[26][27] According to his own account, Fiennes managed to maintain control over his cavalry, who waited until the charging Royalists were close enough "so that their horses' noses almost touched those of our first rank" before firing.[19] Despite this, they were isolated after the retreat of Sandys' men, and were forced to abandon the fight.[19] The Parliamentarian dragoons made a stand on Powick Bridge in order to cover the cavalry's retreat, but Rupert called off the chase at Powick.[28]

Aftermath

The Parliamentarian cavalry rode in alarm all the way back to Pershore, 15 miles (24 km) away, where they met Essex's Lifeguard.[lower-alpha 2] Their relation of the battle, and belief that Rupert's cavalry was still chasing them, broke the Lifeguard, some of whom were carried away in the flight.[30] According to Fiennes, both sides lost around 30 men dead.[28] Other reports place the Parliamentarian losses higher; the historian Richard Brooks estimates that once desertions, drownings and prisoners are taken into account they might have lost in the region of 100–150.[19] The Royalists claimed to have lost no one of note, though many of their officers, including Prince Maurice and Henry Wilmot, were injured.[19][31] The battle established Rupert's reputation as a cavalry commander; soldiers from both sides told stories of the battle, and according to the Royalist commentator Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon, the victory "rendered the name of Prince Rupert very terrible".[32]

No longer threatened by the Parliamentarians, the convoy was able to continue on its journey to the King, and Rupert abandoned the indefensible Worcester and also returned north to Shropshire. The next day, Essex's army arrived in Worcester, where they remained for the next four weeks.[28] Although the city had declared its loyalty to Parliament on 13 September, many in Essex's army thought that Worcester's citizens had helped the Royalists, and the city was accordingly treated poorly: it had to pay for transporting the wounded and burying the dead from the battle, and much of the city was ransacked, particularly the cathedral.[33]

After further build-up of the respective armies, King Charles marched out of Shrewsbury on 12 October, aiming towards London. It was considered that either defeating Essex's field army in battle or capturing London had the potential to quickly finish the war.[34] In the event, the two armies met inconclusively at the Battle of Edgehill, after which the Royalists were able to continue on a slow approach towards London. The Parliamentarians took a less direct route to the capital, but still arrived there first, and after further battles at Brentford and Turnham Green, Charles withdrew to Oxford to establish winter quarters.[35]

Almost nine years later, the final battle of the Third English Civil War, the Battle of Worcester was also fought in and around Powick; Oliver Cromwell's Parliamentarian New Model Army secured a decisive victory over King Charles II. The Puritan preacher Hugh Peter gave a sermon referring to the two battles, "when their wives and children should ask them where they had been and what news, they should say they had been at Worcester, where England's sorrows began, and where they were happily ended".[36]

Notes

- Although termed a "charge", Rupert's cavalry advanced no faster than a quick trot, and remained in a controlled close order formation.[24]

- Essex's Lifeguard was a cavalry troop of cuirassiers commanded by Sir Philip Stapleton. They were considered the most senior cavalry troop in the Parliamentarian army, and were responsible for guarding Essex.[29]

References

- Gaunt 2019, pp. 41–42.

- Gaunt 2019, p. 51.

- Wanklyn & Jones 2014, p. 39.

- Manganiello 2004, pp. 267–268.

- Wanklyn & Jones 2014, pp. 42–46.

- Royle 2005, p. 169.

- Gaunt 2019, pp. 64–67.

- Wanklyn & Jones 2014, p. 43.

- Gaunt 2019, p. 68.

- Gaunt 2019, pp. 67–68.

- Gaunt 2019, p. 67.

- Wanklyn 2006, p. 36.

- Barratt 2004, pp. 120–121.

- Willis-Bund 1905, p. 37.

- Atkin 2004, p. 50.

- Gaunt 2019, pp. 68–69.

- Willis-Bund 1905, pp. 37–38.

- Gaunt 2019, p. 69.

- Brooks 2005, p. 373.

- Gaunt 2019, pp. 69–70.

- Royle 2005, pp. 186–187.

- Roberts & Tincey 2001, pp. 19–22.

- Tincey 1990, p. 17.

- Barratt 2004, pp. 27–28.

- Gaunt 2019, p. 70.

- Royle 2005, p. 187.

- Gaunt 2019, pp. 70–71.

- Gaunt 2019, p. 71.

- Carpenter 2007, p. 84.

- Roberts & Tincey 2001, p. 44.

- Barratt 2004, p. 62.

- Royle 2005, p. 188.

- Atkin 2004, pp. 50–53.

- Scott, Turton & Gruber von Arni 2004, p. 5.

- Gaunt 2019, pp. 79–82.

- Atkin 1998, p. 120.

Bibliography

- Atkin, Malcolm (1998). Cromwell's Crowning Mercy: The Battle of Worcester 1651. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-75091-888-6.

- Atkin, Malcolm (2004). Worcestershire Under Arms: An English County During the Civil Wars. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 1-84415-072-0.

- Barratt, John (2004). Cavalier Generals: King Charles I & His Commanders in the English Civil War, 1642–46. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-128-8.

- Brooks, Richard (2005). Cassell's Battlefields of Britain and Ireland. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-304-36333-2.

- Carpenter, Stanley D.M. (2007). The English Civil War. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-75462-480-6.

- Gaunt, Peter (2019) [2014]. The English Civil War: A Military History. London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-3501-4351-7.

- Manganiello, Stephen C. (2004). The Concise Encyclopedia of the Revolutions and Wars of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1639-1660. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5100-9.

- Roberts, Keith; Tincey, John (2001). Edgehill 1642: The First Battle of the English Civil War. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-991-3.

- Royle, Trevor (2005) [2004]. Civil War: The Wars of the Three Kingdoms, 1638–1660. London: Abacus. ISBN 0-349-11564-8.

- Scott, Christopher L.; Turton, Alan; Gruber von Arni, Eric (2004). Edgehill: The Battle Reinterpreted. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 1-84415-133-6.

- Tincey, John (1990). Soldiers of the English Civil War (2): Cavalry. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 0-85045-940-0.

- Wanklyn, Malcolm (2006). Decisive Battles of the English Civil War. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-454-8.

- Wanklyn, Malcolm; Jones, Frank (2014) [2005]. A Military History of the English Civil War: 1642–1649. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-582-77281-6.

- Willis-Bund, J. W. (1905). The Civil War in Worcestershire, 1642–1646; and the Scotch Invasion of 1651. Birmingham: The Midland Educational Company. OCLC 5771128.