Battle of Chalgrove Field

The Battle of Chalgrove Field took place on 18 June 1643, during the First English Civil War, near Chalgrove, Oxfordshire. A relatively small scale battle, it is best remembered for the death of John Hampden, who died of wounds six days later.

| Battle of Chalgrove Field | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First English Civil War | |||||||

Monument to John Hampden on the battlefield, erected in 1843 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1,150 cavalry; 350 dragoons 500 infantry[2] |

900 cavalry (200 engaged); 100 dragoons | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 20-45 (estimate) | max 50, unknown prisoners | ||||||

Riding through the night of 17 to 18 June, Royalist cavalry under Prince Rupert raided Parliamentary positions around Chinnor. As they returned to Oxford, they were pursued as far as Chalgrove by cavalry under Hampden and Major John Gunter, where Rupert halted. He led a counterattack, which scattered his opponents before the main force arrived under Sir Philip Stapleton; in the course of the fighting, Hampden was wounded in the shoulder.

Combined with his failure to capitalise on the capture of Reading, it caused serious criticism of the Earl of Essex, commander of the Parliamentary army. Royalist morale was significantly boosted, and they went on to achieve a series of victories in the next six months.

Background

When the war began, both sides expected it to be decided by a single, decisive battle, but the events of 1642 showed the need to plan for a lengthy conflict. For the Royalists, this meant fortifying their new capital in Oxford, and connecting areas of support in England and Wales, while Parliament focused on consolidating control of those they already held. Although peace talks were held in February, neither party did so with any conviction, and they ended without resolution.[3]

The Earl of Essex, commander of the main Parliamentarian army, was ordered to take Oxford, and on 27 April, captured Reading. Here he remained until mid May, claiming he was unable to advance further without additional supplies, and money.[4] In response, a convoy was despatched in June, which included £21,000 to pay the soldiers.[5]

The Royalists were even shorter of arms; at the start of the war, Parliament seized the two largest arsenals in England, the Tower of London, and Hull. They also controlled the Royal Navy, and most of the major ports, making it difficult to import them. In February, Queen Henrietta Maria landed in Bridlington, Yorkshire, with an arms consignment from the Dutch Republic.[6]

By mid-June, this vital convoy was at Newark-on-Trent, escorted by 5,000 cavalry from the Northern Army; in an attempt to prevent it reaching Oxford, on 17 June, Essex sent 2,500 men to attack an outpost at Islip. They arrived to find the Royalists waiting, and retreated; as they did so, Scots mercenary Sir John Urry defected, taking with him information on the London convoy, and Essex's troop positions.[7]

Seeing an opportunity, Prince Rupert left Oxford at 16:00 the same day, with 1,200 cavalry, 350 dragoons, and 500 infantry. Essex had concentrated his troops in the north, exposing his southern positions; concerned by this, John Hampden checked his pickets with care before going to bed.[8]

Many of the troops at Chinnor and Postcombe had just returned from the abortive attempt on Islip, and were exhausted; they failed to post guards, and were taken by surprise when the Royalists attacked at 05:00. Having inflicted 50 casualties, as well as capturing prisoners and stores, Prince Rupert decided to withdraw before his line of retreat was cut; by 06:30, his forces were on the road back to Oxford.[9]

While three troops under Hampden and Major John Gunter maintained contact with the Royalists, the local commander at Thame, Sir Philip Stapleton, hastily pulled together a force to attack them. Several senior officers, supposedly in Thame to collect their regiments' wages, helped him form a number of ad hoc units; having collected around 700 men, Stapleton set out in pursuit.[10]

Battle

With Sir Henry Lunsford's infantry leading the way, the Royalists made slow progress due to their prisoners and loot, with their column spread out along two miles. By 08:30, the rearguard was in contact with Hampden and Gunter, who had been joined by 100 dragoons under Colonel Dalbier, an experienced German mercenary. Realising he could not outrun his pursuers, Rupert ordered Lunsford to keep moving, and secure the bridge at Chiselhampton.[1]

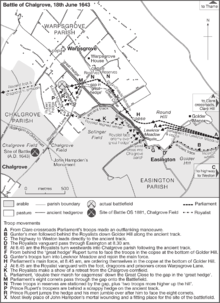

Their route took them along a bridleway, bounded by a 'Great Hedge', a double line of thick, shoulder-high hedgerows used to mark parish boundaries, and prevent cattle straying. This secured their flanks, while Lord Wentworth's dragoons set up an ambush further along the hedgerow (see Map), while Rupert's cavalry formed up in an open field. By now, the Parliamentarian forces on the scene consisted of around 200 cavalry, plus the dragoons.[8]

Dalbier moved his dragoons up to the hedge, and opened fire on the Royalist cavalry; this prompted Prince Rupert into an attack, allegedly leaping the hedge while the rest of his men made their way around. Dalbier withdrew, reinforced by Hampden and Gunter; their troops initially held their ground, but were heavily outnumbered, and broke. For once, Rupert's men halted their pursuit, probably since their horses were exhausted, and withdrew to Chiselhampton, where they remained until the next day.[11]

Most accounts indicate that by the time Stapleton arrived, the fighting was largely over, although it has been suggested otherwise, primarily by Royalist statesman and historian, the Earl of Clarendon.[12] The suggestion Parliamentary casualties contained a disproportionate number of senior officers also originates with Clarendon.[5]

Total casualties are unclear, partly because contemporary reports often fail to distinguish between those incurred at Chinnor, the skirmish with the rearguard, and the battle itself. The Royalists reported a total of 45 for both sides, Essex suggested 50 each, including Gunter, who was killed close to the hedge, and Hampden. Shot twice in the shoulder, the wound became infected, and he died six days later. Later claims these injuries were caused by the explosion of his own pistol have not been substantiated.[13]

Aftermath

Chalgrove Field cemented Prince Rupert's reputation, emphasising his qualities of drive, determination, and aggression.[14] In only a few hours, he put together nearly 2,000 men, devised a plan, and carried it out, while his aggressive counter-attack kept Stapleton at a distance. It also minimised his weaknesses, one being his cavalry's ill-discipline, which cost the Royalists victory at Edgehill, and led to defeat at Naseby; at Chalgrove, this was limited by their horses being exhausted after a night of hard riding. Capable of inspiring great loyalty among subordinates, like Wentworth and Legge, he was less successful with his peers, the quarrel with Newcastle contributing to defeat at Marston Moor.[15]

It increased discontent with Essex, whose sole achievement in 1643 was to capture Reading; the attack on Islip was slow and ponderous, in contrast to that led by Rupert. Despite warnings of the likelihood of a raid, no precautions were taken, and without Hampden and Gunter, the Royalists would have made it home without being intercepted. The damage to his reputation was sealed when Rupert's men spent the next day at Chalgrove distributing their loot, and preparing for a triumphal entry into Oxford, while the Parliamentarian army looked on.[16]

Chalgrove ended any danger to the Royalist arms convoy, which entered Oxford in early July. More importantly, it established a psychological edge over their opponents, confirmed on 25 June when Urry attacked Wycombe. Essex withdrew from Oxfordshire, allowing Prince Rupert to support operations in the west, culminating in the capture of Bristol on 26 July.[17]

Hampden's death was seen as a major blow; his close friend Anthony Nicholl wrote; 'Never Kingdom received a greater loss in one subject, never a man a truer and more faithful friend.'[18] His reputation and man management skills had been vital in minimising internal divisions, particularly after the exposure of Edmund Waller's Plot on 31 May. Waller had close links to many Parliamentarian leaders, including his cousin, William Waller, and Essex. [19] The death of John Pym in December meant Parliament's two most prominent leaders left the scene in less than six months, during a period of almost unbroken Royalist success.[20]

In 1843, George Nugent-Grenville, a Whig radical politician and author of the hagiographic Memorials of John Hampden, paid for the Hampden Monument, located 700 metres south of the main site.[21] Following an extensive debate over whether it constituted a 'battle' or 'skirmish', English Heritage designated it a registered battlefield in 1995.[5]

References

- Stevenson & Carter 1973, p. 348.

- Battle of Chalgrove 2020.

- Royle 2004, pp. 208–209.

- Wedgwood 1958, pp. 217–218.

- Battle of Chalgrove 1643 (1000006).

- Royle 2004, p. 225.

- Stevenson & Carter 1973, p. 347.

- Stevenson & Carter 1973, p. 349.

- Royle 2004, p. 229.

- Lester & Lester 2015, p. 34.

- Stevenson & Carter 1973, pp. 351–353.

- Clarendon 1704, pp. 262–263.

- Lester & Blackshaw 2000, pp. 21–24.

- Spencer 2007, p. 55.

- Wedgwood 1958, p. 315.

- Royle 2004, pp. 230–231.

- Wedgwood 1958, pp. 233–234.

- Adair 1979, p. 17.

- Wedgwood 1958, p. 219.

- Wedgwood 1958, p. 278.

- Hampden Monument (1059742).

Sources

- Adair, John (1979). "The Death of John Hampden". History Today. 29 (10).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Battle of Chalgrove". Battlefields Trust. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- Clarendon, Earl of (1704). The History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England; Volume II (2019 ed.). Wentworth Press. ISBN 978-0469445765.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Historic England. "Battle of Chalgrove 1643 (1000006)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Historic England. "Hampden Monument (1059742)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- Lester, Derek; Blackshaw, Gill (2000). The Controversy of John Hampden’s Death. Chalgrove Battle Group. ISBN 978-0953803408.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lester, Derek; Lester, Gill (December 2015). "The military and political importance of the battle of Chalgrove 1643". Oxoniensia. 80.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Royle, Trevor (2004). Civil War: The Wars of the Three Kingdoms 1638–1660 (2006 ed.). Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-11564-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spencer, Charles (2007). Prince Rupert: The Last Cavalier. Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-297-84610-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) ::Stevenson, John; Carter, Andrew (1973). "The Raid on Chinnor and the Fight at Chalgrove Field". Oxoniensia. Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society. XXXVIII.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wedgwood, CV (1958). The King's War, 1641-1647 (2001 ed.). Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0141390727.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)