Pamphlet wars

Pamphlet wars refer to any protracted argument or discussion through printed medium, especially between the time the printing press became common, and when state intervention like copyright laws made such public discourse more difficult. The purpose was to defend or attack a certain perspective or idea. Pamphlet wars have occurred multiple times throughout history, as both social and political platforms. Pamphlet wars became viable platforms for this protracted discussion with the advent and spread of the printing press. Cheap printing presses, and increased literacy made the late 17th century a key stepping stone for the development of pamphlet wars, a period of prolific use of this type of debate. Over 2200 pamphlets were published between 1600–1715 alone.[1]

Pamphlet wars are generally credited for powering many key social changes of the era, including the Protestant Reformation and the Revolution Controversy, the English philosophical debate set off by the French Revolution.

History of the pamphlet in England

The growth of British literature started in the 1520s. It was generally used in this decade and several following for debates over different religious practices. It was a pattern in Europe that the press was used in order to war over religion, and England was no exception. Henry VIII used literature to try to rewrite history, attempting to justify his break from Rome and the Catholic Church.[2] During the subsequent reigns of Edward and Mary, literature was used not only for religious purposes, but also as a sort of propaganda war. The written word had enormous potential to sway the common opinion.[2] In the 1560s, print was first used for conveying news. In 1562, the first pamphlets were reported, which discussed the English forces sent to aid the French Huguenots. In 1569, pamphlets were again used to report the revolt of the Northern Earls and the Rebellion of 1569. Beginning in the 1580s pamphlets began to replace broadsheet ballads as the means to convey news to the general public. The pamphlet gained more and more popularity over the next century until 1688, by which time it was the main way to gain public support for an idea.[2] After the Glorious Revolution, the pamphlet lost some popularity due to the emergence of newspapers and periodicals,[3] but continued to be an important factor, as illustrated by the Revolution Controversy a full century later in the 1790s.

Pamphlet printing

Coming from a Latin word, "pamphlet" literally means "small book." In the early days of printing, the format of the book or pamphlet depended on the size of the paper used and the number of times it was folded. If a page was only folded once, it was called a folio. If it was folded twice, it was known as a quarto. An octave was a paper folded three times. A pamphlet was usually 1-12 sheets of paper folded in quarto, or 8-96 pages. It was sold for one or two pennies apiece.[2] The printing of a pamphlet involved many people: the author, the printer, suppliers, print-makers, compositor, correctors, pressmen, binders, and distributors. Once the pamphleteer had written the pamphlet, it was sent to the printing house to be corrected, set into type, and printed. The papers were then given to the printer's warehouse-keeper, who bundled the copies and sent them to the bookseller, who was probably the one financing the printing. He was responsible to bind the pamphlets, usually by sewing them, and then sold them wholesale to individual bookselling vendors. The booksellers then sold them from a stall in the marketplace.[2]

Pamphlet subjects

Pamphlets began as the means of conveyance for religious debates, and therefore religious topics were one of the main subjects they dealt with.[1] The definition of a pamphlet came to mean a short work dealing with social, political, or religious issues.[2] Typical topics included the Civil war, Church of England doctrines, Acts of Parliament, the Popish Plot (see below), the Stuart Era, and Cromwell propaganda.[1] In addition, pamphlets were also used for romantic fiction, autobiography, scurrilous personal abuse, and social criticism. They contained much of the propaganda of the 17th century in the midst of the religious and political turmoil. They were also used for debates between the Puritans and the Anglican. During the Glorious Revolution, pamphlets were political weapons.[3]

Authors

.jpg)

There were many authors of pamphlets. However some of the more popular authors include Daniel Defoe, Thomas Hobbes, Jonathan Swift, John Milton, and Samuel Pepys.[1] Also included in the midst are Thomas Nashe, Joseph Addison, Richard Steele, and Matthew Prior.[3] In 1591–1592, Robert Greene released a series of pamphlets which later inspired many other authors including Thomas Middleton and Thomas Dekker.[2]

Critics

Pamphlets, along with their vast popularity, received criticism. There were many in the time period who believed that pamphlets were full of foolishness. They thought the pamphlets were not good enough literature and that they would turn people from "good" writing. They believed that pamphlets would be the end of the great volumes of literature and that great writing would be forgotten.[2]

News reporting

Pamphlets made a great difference in the way news was reported to the general public. With the publication of pamphlets, it was no longer difficult for people to hear of events taking place far away. The closer the occurrence was to London, the easier and faster people heard of it. For example, the Battle of Edgehill took place on 23 October 1642. The first pamphlet reporting the incident was printed on 25 October 24 hours after some of the orders reported had been given. While not entirely accurate, and hurriedly made, the pamphlet nonetheless was able to tell the general public what had happened in the battle. A more accurate, specific, and readable account was available in a pamphlet printed on 26 October, and the "authorized" version was available only five days after the battle took place.[4]

Marprelate pamphlets

In 1588, a series of pamphlets marked the turning point for the Puritans, dividing them from other Protestants in the country. These pamphlets set forth Puritan doctrines and aroused a lot of controversy. The authors wrote under the pseudonym of Martin Marprelate, and his two sons of the same name. The true authors were never discovered. The series of pamphlets was written with the aim to provoke a response from authorities in regards to action they wanted taken against censorship. The series was among the first to engage the audience, asking questions and addressing the reader directly.[2]

Early pamphlet wars

Elizabethan pamphlet wars

As a means of forming or swaying public opinion, pamphlets like these had a in both influencing society, and the content being influenced by society.[5] During the 16th century and continuing for a short while in the early 17th century in England there was rise in the use of pamphlet wars to discuss a myriad of issues spanning from the civil war, to religious freedoms and the roles of women in society. The Queen herself participated in these discussions, making sure that she was widely read and understood by her people in order to gain favor and establish herself as the monarch despite being a woman. Examples of her use of this medium appear in To the Troops at Tilbury written in 1588, On Mary's Execution written in 1586, and many more. Another famous writer of this period to take advantage of the pamphlet includes Aemilia Lanyer, famous for her arguments concerning the role of women. A common idea promoted by many literary works and the general attitude towards females, Lanyer's work "Eve's Apology in Defense of Women" refuted the belief that Eve is responsible for the fall of man. A very uncommon and unpopular stance to take, Lanyer accomplishes her defense through structuring it as an apology, one of the earliest subversive feminist texts.[6] Similarly, Francis Bacon wrote his Essays to promote his idea of morality and other complicated social issues. For example, his work, "Of Love" examines the various understandings of the concept of love, particularly as it was perceived during the Elizabethan era.[7]

Eikon Series

In 1649, and until 1651, some five pamphlets were published in a debate about the execution of Charles I, the king of Ireland, Scotland, and England. The king himself, pre-death, wrote the first pamphlet in the discussion (Eikon Basilike: The Portraiture of His Sacred Majesty in His Solitudes and Sufferings), painting himself a martyr. In the following months, what came to be known as the "Eikon" series were published: Eikon Alethine, Eikon e Pistes, Eikonoklastes, and Eikon Aklastos, ("eikon is greek for "image). all alternately attacking or defending the idea surrounding the king's death and his own pamphlet. This war of words was about preserving or erasing the memory and thoughts of Charles I. It was a battle about the significance of his execution, and the execution of a monarch in general, which was seen as an execution of the personification of law and power.

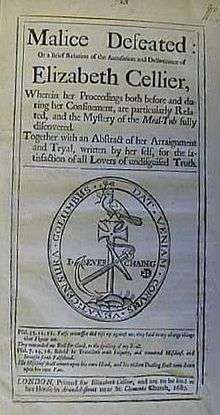

Popish Plot and Elizabeth Cellier

In the 1680s, after being acquitted of the "Meal-Tub Plot" for which she was accused, Elizabeth Cellier wrote Malice Defeated, which, along with The Matchless Picaro, sparked a pamphlet war surrounding debate of the ascension of a Catholic king to the throne. She, and many associates, published several dozen works regarding the issues of their time in dealing with the Popish Plot. The repercussions of Cellier's writings were widespread as members of her company were arrested and punished. Cellier herself was convicted of libel and received harsh punishment, including being stoned and imprisoned for a time.

Effects

These early pamphlet wars served to change the way literary, and even social, conversations were viewed and carried out. They also created new ways of conversation, and new styles of language. Elizabeth Cellier was also a key figure in her defiance of normal gender roles and willingness to publicly submit her writings and vocalize her views. Throughout history they have allowed for discussion on a widespread and influential level.

Notes

- "British Pamphlets, 17th Century." British Pamphlets, 17th Century. The Newberry. Web. 14 March 2015. http://www.newberry.org/british-pamphlets-17th-century Archived 2017-10-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Raymond, Joad. Pamphlets and Pamphleteering in Early Modern Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print.

- "Pamphlet | Literature." Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Web. 14 March 2015.

- Greenburg, Steven. "Dating Civil War Pamphlets, 1641–1644." The North American Conference on British Studies. Web. 14 March 2015.

- Jurdjevic, Mark (1 January 2005). "Review of A Renaissance of Conflicts: Visions and Revisions of Law and Society in Italy and Spain". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 36 (2): 533–535. doi:10.2307/20477408. JSTOR 20477408.

- "The Norton Anthology of Literature by Women". wwnorton.com. W. W. Norton & Company.

- "Essays of Francis Bacon – Of Love (The Essays or Counsels, Civil and Moral, of Francis Ld. Verulam Viscount St. Albans)". authorama.com.

References

- Grossman, Marshall. Pamphlet Wars: To Kill a King! 29 February 2012.

- Winkelman, Carol L. The discourse of conflict and resistance: Elizabeth Cellier and the seventeenth-century pamphlet wars. The University of Michigan, 1992.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20171002012903/http://www.newberry.org/british-pamphlets-17th-century