Battle of Kallo

The Battle of Kallo was a major battle of the Eighty Years' War and Thirty Years' War. It was fought on 20 June 1638 near the fort of Kallo, located on the left bank of the Scheldt river, between a Dutch army under the command of William of Nassau-Hilchenbach, and a Spanish army led by the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand, governor of the Spanish Netherlands. As the Dutch approached with the aim of surrounding the city of Antwerp, the Cardinal-Infante managed to assemble an army and almost miraculously repelled the much larger Dutch force, which lost several hundred men dead (one of whom was William of Nassau's only son), another 2,500 taken prisoner, and significant amounts of artillery and baggage. The Battle of Kallo was the largest action of the Spanish-Dutch War,[9] as well as the only pitched battle and the worst Dutch defeat of the late Eighty Years' War.[4]

Background

While no major offensive operation was carried out against the United Provinces by the Spanish Army of Flanders during 1636–37,[10] in July 1637 the statholder Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange, marched into northern Barbant in command of an army of 18,000 soldiers and invested the Spanish-ruled city of Breda.[10] Garrisoned by 3,000 Spaniards, Italians, Wallons and Burgundians, Breda was one of the main fortresses of the Spanish Netherlands and a symbol of the Spanish power in Europe.[11] A Spanish force under the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand attempted to relieve the garrison of the city, but failed to dislodge the besiegers.[12] Ferdinand decided move with his army to the valley of the Meuse, where he took Venlo and Roermond after two fierce bombardments, in order to distract Frederick Henry.[9] However, he had to turn back shortly after, alarmed by the French advances in Artois, Hainaut and Luxembourg, and could not prevent the fall of Breda.[12]

For the campaign of 1638, King Philip IV instructed the Cardinal-Infante to undertake an offensive strategy against the Dutch in order to subject them to massive pressure and force them to agree a favourable truce and the restoration of their conquests in Brazil, Breda, Maastricht, Rheinberg and Orsoy.[13] The main objective of that year would be the capture of Rheinberg, which would give to Spain a crossing point in the Lower Rhine and contribute to tightening the blockade over Maastricht.[12] Ferdinand was also ordered, when the offensive operations had finished, to quarter his army near the Dutch frontier in order to protect Antwerp, which had become more vulnerable since the loss of Breda, and even to reinforce the garrisons of many secondary fortresses.[12] In the end, however, the Spanish were pinned to the defensive by a coordinated Franco-Dutch attack in May 1638.[8] Marshal Châtillon laid siege to Saint-Omer covered by Marshal La Force in Picardy while Frederick Henry marched on Antwerp commanding an army of 22,000 soldiers, determined to besiege the city.[3]

Battle

Dutch advance

A Dutch vanguard of 6,000 Dutchmen, Germans and Scots under Prince William of Nassau was dispatched ahead of the main army with orders to capture various forts and redoubts placed on the left bank of the Scheltd river.[4] Initially the army was going to Bergen op Zoom, where Frederick Henry had sent 50 river barges, but then moved to Lillo.[14] On the night of 13/14 June they crossed the Scheldt, landing at Kildreck, and easily occupied the Fort of Liefkenshoek, near the village of Kallo.[14] According to a Spanish official letter from June 30, 1638, the commander of the fort had previously been bribed with 24,000 silver coins to open the gates as they approached.[5] According to other source, the man, a captain called Maes, was not involved in any treachery but asked permission from the Dutch to save the life.[14] The remaining garrison, caught by surprise, was massacred.[5] William proceeded the following morning to attack the Forts of Sainte Marie and Isabelle, the latter built on the levee of Voorderweert.[15] He also ordered the dykes of the Polder of Melsele to be demolished with the aim of flooding the area,[15] but the low tide prevented this.[15]

Over the next four days, the Dutch sappers worked to improve the defenses of the main Fort of Liefkenshoek.[5] Large amounts of earth and other necessary materials were brought aboard river barges from the Fort Lillo, located on the Dutch-controlled opposite riverside, which allowed the sappers to build high and wide embankments.[5] William garrisoned half of his troops in those entrenchments, sending the remaining to harass the Forts of Sainte Marie and Verrebroek.,[15] from where they were receiving artillery fire and skirmishes were made by the Spanish to regain the levees between Kallo and Sainte Marie.[14] An assault against this fort was rejected by its German garrison on the 17th, although the following day it was abandoned by its defenders and occupied by William's troops. Weerdick was taken by assault and captured the same day.[15] Some sources claim that William's only son was killed during these actions.[14]

Spanish counter-attack

The Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand, alarmed, requested his Imperial general Ottavio Piccolomini to immediately come to Antwerp with his army. Piccolomini was then en route to Valenciennes with 4,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry soldiers to relieve the besieged town of Saint-Omer together with the Prince Thomas Francis of Carignano.[16] Ferdinand went himself to the city determined to recover himself the lost forts.[5] He gave the command of the citadelle of Antwerp to Don Felipe da Silva and that of the city to Anthonie Schetz, baron of Grobbendonk, and even ordered the Marquis of Lede to come from the Meuse, where he was camped, with his troops.[16] Warned of this maneuvers, William garrisoned all his troops to wait for a counterattack.[15]

.jpg)

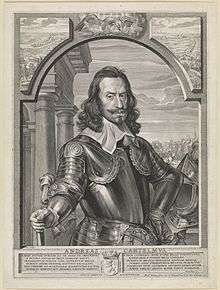

Ferdinand divided his army into three parts.[17] The General of the Artillery Andrea Cantelmo would lead the main force, consisting of 3,000 men divided on 5 companies of Spanish veterans of the Tercio of Velada, all the Tercio of Duchino Doria, and some companies of Walloon soldiers.[17] The Marquis of Lede would attack in charge of 5 companies of the Old Tercio of Fuenclara, the Walloon Tercio of Ribacourt, the Lower German regiment of Brion, and other soldiers of Nations,[18] a total of 2,000 men.[16] The last force, whose strength was also of 2,000 men,[16] was put in command of Count of Fuenclara and consisted of 15 companies of his own Tercio.[19]

On 20 June the Spanish army crossed the Scheltd river and took positions near Beveren.[15] The battle, one of the bloodiest of the war, began that night with the Spanish army storming the Dutch positions and lasted for 12 hours.[19] Cantelmo fell over the fortifications through the leeve of Warbrok; the Marquis of Lede did it from Beveren, and the Count of Fuenclara in the fort of Sainte-Marie.[16] At first the Dutch soldiers managed to repel the Spanish, but they were finally overrun and fled in disorder.[20] About 2,500 men were killed or drowned in attempting to escape,[20] while another 2,500 were captured. The whole of the artillery, 3 standards, 50 flags and 81 river barges were taken by the Spaniards.[7] The Forts of Liefkenshoek and Verrebroek were reoccupied during the action, which cost the Cardinal-Infante 284 men dead, among them many captains, and 822 wounded. According to the same Spanish official letter from 30 June, William of Nassau's only son was taken prisoner in the Fort of Liefkenshoek[21] and shot dead by his captors to prevent his rescue by a group of Dutch soldiers.[21]

Aftermath

The victory of Kallo was described by the Cardinal-Infante to King Philip as the "greatest victory which your Majesty's arms have achieved since the war in the Low Countries began", and by the Dutch as "a great disaster".[22] The recapture of the key fortress of Kallo forced Frederick Henry to abort the whole offensive,[9] which turned as one of the worst Dutch defeats of the war,[4] thus undermining the reputation of the statholder.[3] Shortly after two of Ferdinand's generals, Ottavio Piccolomini and Prince Thomas of Carignano, routed in command of an Imperial-Spanish force the French army under the Marshals Gaspard III de Coligny and Jacques-Nompar de Caumont,[8] which retreated from Saint Omer with the loss of 4,000 men.[4] Piccolomini's Imperials also overran some Dutch outposts in Cleves.[9] In an attempt to restore the situation, Frederick Henry laid siege to Geldern in command of 16,000 men, but was forced into a costly retreat by the Cardinal-Infante, who succeeded in breaking his lines of circumvallation.[8] The defensive campaign of 1638, in all, was exceptionally successful for the Spanish.[8]

Notes

- The capture of the fortress of Kallo was crucial to capturing Antwerp. Sanz p. 141

- The Dutch offensive was aborted due to the defeat. Guthrie p. 168

- Wilson p. 661

- Guthrie p. 190

- Memorial histórico español p. 445

- De Cevallos y Arce p. 79

- Mariana p. 69

- Israel p. 83

- Guthrie p. 168

- Israel p. 80

- Israel pp. 80–81

- Israel p. 81

- Israel p. 82

- Michaud/Poujoulat, p. 239

- Annales des travaux publics de Belgique p. 45

- Michaud/Poujoulat, p. 240

- De Cevallos y Arce p. 178

- De Cevallos y Arce pp. 178–179

- De Cevallos y Arce p. 179

- Davies p. 610

- Memorial histórico español p. 446

- Albi p. 266

References

- Belgium. Ministère des travaux publics (1844). Annales des travaux publics de Belgique (in French). 2. Société royale belge des ingénieurs et des industriels, Belgium. Administration des ponts et chaussées, Belgium. Ministère des finances et des travaux publics. Brussels: Geomaere.

- Albi, Julio (1999). De Pavía a Rocroi: los tercios de infantería española en los siglos XVI y XVII (in Spanish). Balkan. ISBN 84-930790-0-6.

- Michaud, Joseph Fr.; François Poujoulat; Jean Joseph (1853). Nouvelle collection des mémoires pour servir à l'histoire de France: depuis le XIIIe siècle jusqu'à la fin du XVIIIe; précédés de notices pour caractériser chaque auteur des mémoires et son époque; suivi de l'analyse des documents historiques qui s'y rapportent (in French). Guyot Frères.

- De Cevallos y Arce, Lorenzo (1842–1895). Sucesos de Flandes en 1637, 38 y 39 in Coleccion de libros españoles raros ó curiosos (in Spanish). LXXV. Madrid: Impr. de la Viuda de Calero.

- Guthrie, William P. (2001). The later Thirty Years War: from the Battle of Wittstock to the Treaty of Westphalia. Westport, USA: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32408-6.

- Israel, Jonathan Irvine (1997). Conflicts of empires: Spain, the low countries and the struggle for world supremacy, 1585–1713. London, UK: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-85285-161-3.

- De Mariana, Juan (1839). Historia general de España (in Spanish). 9. Madrid: Impr. de Francisco Oliva.

- Davies, Charles Maurice (1842). History of Holland, from the beginning of the tenth to the end of the eighteenth century. 2. London: J. W. Parker.

- Memorial histórico español: colección de documentos, opúsculos y antigüedades que publica la Real Academia de la Historia (in Spanish). 14. Madrid: La Academia. 1862.

- Martín Sanz, Fernando (2003). La política internacional de Felipe IV (in Spanish). Fernando Martín Sanz. ISBN 978-987-561-039-2.

- Wilson, Peter H. (2009). The Thirty Years War: Europe's Tragedy. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03634-5.