Battle of Turnhout (1597)

The Battle of Turnhout also known as the Battle of Tielenheide was a military engagement which took place on 24 January 1597 in the border area between the Northern and Southern Netherlands at Turnhout during the Eighty Years' War and the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604).[9]

After a small skirmish both armies confronted each other on an area of heathland. The Spanish cavalry was driven off, after which the English and Dutch cavalry fell upon the straggling Spanish infantry who were routed with heavy casualties.[7][10]

Background

After the successful attack on Cadiz in 1596 the English army led by Sir Francis Vere were urgently required back in the Netherlands and went there directly. Due to the raid's damages Spain had gone bankrupt for the third time which meant that payments to the army dried up, which led to mutinies.[11] During the winter of 1596/7 Archduke Albert's Spanish army of 4,600 under the command of the Burgundian Philibert de Rye, Count Varax, had advanced to the village of Turnhout, about twenty miles south of Breda; their design was to surprise the town of Tholen on a rare winter offensive.[12]

The Dutch Stadtholder, Maurice of Nassau, had received orders from the States General to collect a force at Geertruidenberg to counter the Spanish threat in the area of Turnhout. Though the town had not been walled, Turnhout was an important strategic town - it held a small castle, surrounded by a moat and contained a garrison of forty men.[13] A force of nearly 6,000 men with two demi-cannons and two field pieces, was assembled at Geertruidenberg. Six companies of Dutch infantry were under Maurice - the Counts of Hohenlohe, Brederode, and Solms arrived with contingents gathered from their various garrisons.[12] Sir Francis Vere led the English force once more - nearly two thirds of Maurice's army were in fact English and Scots. A minority were subsidized allied troops or 'religious volunteers' most of whom were long-term mercenaries sent by Elizabeth I. Among these were Sir Alexander Murray's regiment of Scots, as well as eight companies of English infantry under the command of Captain Henry Docwra. The cavalry totalled 800 men commanded by Marcellus Bacx and included a contingent of a hundred elite pistoleers made up of volunteers from among the English gentry, 'the gentlemen of the (Protestant) religion', under Sir Robert Sydney and Sir Nicholas Parker.[1][14]

On January 23, 1597 the expedition marched out of Geertruidenberg in four divisions, with the cavalry on the flanks and stopped off to camp at Ravels on the frozen ground.[13]

The Spanish army under the command of Varax consisted of four battalions of infantry; the elite Spanish 'Naples' Tercio regiment under the Marquis of Treviso, the Germans under the Count of Sulz, and a couple of Walloon and Burgundian regiments under the Comtes de Hachicourt and de Barlaymont.[13] There were five squadrons of Spanish cavalry commanded by Nicolo Basta. The regiments of horse were commanded by Juan de Cordova, Alonzo de Mendoza, Juan de Guzman, Alonzo Mondragon, and a Flemish force under de Grubbendonck.[12] These were split into two units, one of heavy lancers and the other of lighter 'herreruelos' (mounted harquebusiers).[15]

At midnight Maurice broke up his camp and after a forced march they reached the outskirts of Turnhout in the neighbouring village of Tielen by midnight.[16]

Battle

Varax heard reports of Maurice's army having approached not far from Turnhout itself. He immediately ordered a retreat and by dawn the whole of the Spanish force were in the process of withdrawing to Herentals.[16] Maurice soon discovered that the rear guard of the Spanish had just marched out of the village. The country was intersected in all directions by hedges and ditches and having reached the banks of the River Aa, Varax removed all but one plank from the wooden bridge that transversed it. Parties of Spanish musketeers were stationed on the other side to contest any crossing attempt by Maurice, although the English advance guard swiftly forced them off.

[14] English carabineers and musketeers were sent forward to engage the Spanish rearguard and a skirmish ensued which continued for five miles.[1] Dutch musketeers crossed the bridge, while others, with the cavalry, traversed the river through a nearby ford. The Spanish were now in full retreat, while Maurice ordered the whole of the Anglo-Dutch cavalry to advance rapidly in pursuit, leaving his infantry well behind.[17]

Having come across a large wood further on from the river, Vere called up his detached musketeers and placed them along the edges to conceal them.[17] These skirmishers kept up a constant harassing fire on the Spanish rearguard, while Vere along with sixteen horsemen followed them along the highway in full sight and at the same time sent back a report to Maurice to come up in support. Vere had his horse shot from under him which slightly wounded his leg, but continued to lead on foot, until he was remounted. This skirmish between the Anglo-Dutch scouting force and the Spanish rearguard lasted for over three hours until the main body of the former's cavalry arrived. The Spanish had by then emerged onto an open heath, suitable for cavalry action.[18]

Varax had his infantry formed in four solid squares of pikemen in the open space of the heath, with musketeers on the flanks as was standard practice for the Spanish tercios. His cavalry and wagons had entered an enclosed lane beyond. The first square consisted of Germans led by the Count of Sulz, then came the Walloons and Burgundian tercios. The Marquis of Treviso brought up the rear with a force of Italian and Spanish veteran tercios. Vere had followed them, until all of Maurice's cavalry had joined with him having emerged from the wood. The Anglo-Dutch then formed on the open heath in front of the Spanish.[19]

.jpg)

The Spaniards steadily continued their march but as they became aware of the allied movements on their left, their cavalry changed position and transferred from the right to the left of the line and rode between the infantry and the belt of woods. After the first volley by Vere's musketeers the Spanish harquebuisers on foot broke and fled. Varax ordered his cavalry to protect the retreat but Count Hohenlohe and his Dutch cavalry charged the Spanish right flank, as Vere followed suit upon their rear.[20] Hohenlohe fell upon Sulz's regiment of Germans while the rearguard consisting of Treviso's tercios was assailed by Vere's English and Bacx's Dutch cavalry. The surprise was complete; the Spanish cavalry which included the famed squadrons of Guzman, Mondragon, and Mendoza were hit hard at the first onset and within moments retreated for the pass. Most of them escaped through the hollow into the boggy ground beyond. Several companies of Parker's cavalry galloped down the Herentals road, in pursuit of the Spanish cavalry and baggage.[6]

With the Spanish cavalry having been driven off, the Dutch and English cavalry fell upon the straggling Spanish infantry. The Walloon regiments tried to form a line with the flank protected by a copse, but their morale was already low after witnessing the flight of their cavalry. When they saw in the distance the mass of Dutch infantry appearing to support their cavalry they broke into a rout and tried to swim across the Aa river to reach Herentals. The musketeers of Sultz's regiment fell back in confusion upon the pikemen behind them and the whole formation promptly surrendered en masse upon being charged by the Anglo-Dutch cavalry. The veteran tercios of Treviso however managed to deploy in combat formation and resisted manfully for some time, but Vere and Bacx's charge upon them was decisive.[1] The Dutch and English troopers rode up very close to the massed ranks of the Spanish infantry and discharged their pistols and carbines at point blank range, inflicting carnage. Varax, fighting in the front line with his men, was among the casualties.[20] The cuirassiers' fire opened gaps within the Spanish ranks into which the troopers rode in and started attacking the formation from within, rapidly causing a rout.[6]

While the veteran Spanish tercio were being broken, the surviving Germans in the front and the other tercios in the rear had been simultaneously shattered and the panicked survivors swamped the two other regiments, those of Hachicourt and La Barlotte which were placed between them, masking their field fire and spreading panic among them.[19] The English and Dutch soon broke these formations as well and put nearly all of the Spanish infantry into rout. The pursuing cavalry harried them and the Spanish infantry were 'cut down with terrible slaughter'.[14] Parker's cavalry had in the meantime gone through the pass and plundered the Spanish baggage train.[1] The Spanish had been completely routed and the battle had lasted no more than half an hour.[8]

The rest of the Spanish managed to retreat to Herentals where Nicolo Basta took command and rallied the survivors.[21]

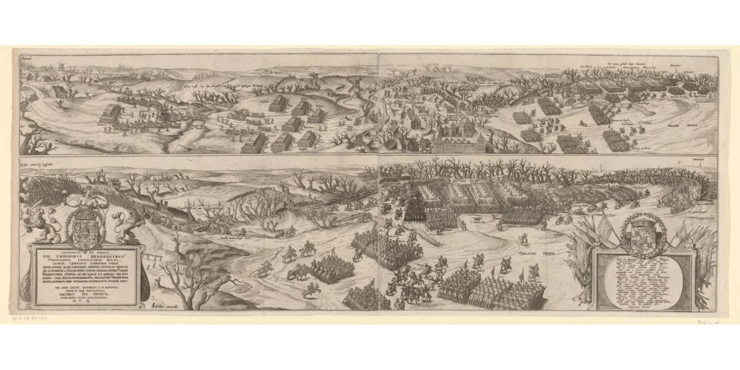

Top: the advancing army under Maurice in pursuit of Spanish troops from Ravels via Turnhout to the Tielenheide

Bottom:the battle on the Tielenheide and the fleeing Spanish cavalry.

Aftermath

Out of 4,000 Spanish soldiers and 500 horsemen nearly over 50% were casualties; 2000 were killed or wounded. In addition thirty-eight ensigns were taken and prisoners numbered around 600.[7] Of the allied force only fifty were casualties including ten killed. The whole action was won by around 800 Dutch and English horsemen and the majority of the Dutch infantry were never brought into action.[21] That night the victors rested in Turnhout and the next morning the castle there capitulated and the Dutch promptly burned parts of it. However, in a few days Maurice had to leave the city before the arrival of Spanish reinforcements led by the Archduke Albert who after hearing of the defeat left his winter quarters. The Spanish Tercios of Francisco Velasco and several units of cavalry, which together with the survivors of the battle advanced against him. The allied force then began their return march to Geertruidenberg.[6] The victory at Turnhout therefore did not result in any long term strategic gain since there was no follow up.[2]

On 8 February Maurice returned to The Hague - the Spanish standards captured from the battle were strung up in the Ridderzaal (the political headquarters of the States General) as a symbol of victory.[9] The prisoners were treated with kindness and the wounded were cared for, even the body of Varas was sent to the Archduke. In return Albert assured the Dutch Prince that he would follow his generous example for the duration of the war.[20] The English under Vere and Sidney greatly distinguished themselves.[6] Vere accompanied Sidney to Willemstad, wrote his official despatches and gave them to one of Sidney's captains to deliver in England. Both generals spoke generously of each other - Vere thought that Sidney exceeded well in battle, being one of the first that charged. Sidney reported that the victory was only due to Vere.[2]

News of the battle of Turnhout was received in England with great rejoicing, and congratulations poured in on all sides. The satirist Stephen Gosson composed a sermon called the Trumpet of Warre a justification of war with Spain. The battle was even dramatized in London, and introduced on the stage known as the Overthrow of Turnholt.[22] All of the officers who were present at the battle were impersonated.[2]

He that played Sir Francis Vere got a beard resembling his, and a watchet satin doublet with hose trimmed with silver lace. Sidney and the others were among the dramatis personæ, and honorable mention was made of their services in seconding Sir Francis.[6]

Queen Elizabeth I herself wrote to Vere on February 7, 1597, in the following terms:

It is no news to hear, by the late defeat at Turnhout, that your presence and that of the other English in the service, has furthered both your own reputation and its success: yet we wish to signify our good liking of the report we hear of your services.[6]

Analysis

At the time the battle had great importance for the evolution of mounted warfare for two reasons. The first impact was that Maurice's army had demonstrated the superiority of the new type of cavalry, the cuirassiers or reiters, as used by Henry IV of France at the battle of Ivry. The cuirassiers wore half armour and a light headpiece and were armed with several pistols but also carried carbines as well as a sword.[23] No lance was carried so instead of being arrayed in a thin line to maximize the number of lance being deployed they charged in a dense formations (eight in depth) and fired their pistols only in the moment of contact. This tactic, which had already defeated French gendarmes (lancers in full armour) at Ivry, proved to be effective as well against the lighter Spanish demi-lancer.[24] The second impact was that the Dutch and English cuirassiers, with the support of a few hundred musketeers, had destroyed a regiment of Spanish tercios without the help of their own heavy infantry. These lessons on the value of the cuirassiers were quickly learned and most European armies abandoned the employment of lancers soon after, with only the Poles retaining them within their famed husaria. The Spaniards finally drew their conclusions after the defeat at Nieuwpoort three years later.[25]

Cultural

Music composer Kevin Houben commemorated the battle in his concert work, Thyellene, battle on the heath. In September 2008, Brassband Kempenzonen Tielen played this work on the site where once the battle took place.

The defeat of Varax inspired the writing of the hymn We Gather Together.

References

- Notes

- Fissel pp. 170-73

- Hadfield & Hammond 2010, p. 133.

- Weigley 2004, p. 13.

- Van Nimwegen 2010, p. 164.

- Van der Hoeven 1997, p. 71.

- Markham pp. 260-61

- Van Nimwegen 2010, p. 165.

- Van der Hoeven 1997, p. 72.

- Gosman & Peeters p. 66

- Nolan 2006, p. 878.

- Pedro de Abreu: Historia del saqueo de Cádiz por los ingleses en 1596, escrita poco después del suceso, fue vetada en su época por las críticas vertidas contra la defensa española. Se publicaría por vez primera en 1866.

- Markham pp. 254-55

- Motley, John Lothrop. History of the United Netherlands: from the death of William the Silent to the Synod of Dort, with a full view of the English-Dutch struggle against Spain, and of the origin and destruction of the Spanish armada (Volume 3). pp. 424–25.

- Knight, Charles Raleigh: Historical records of The Buffs, East Kent Regiment (3rd Foot) formerly designated the Holland Regiment and Prince George of Denmark's Regiment. Vol I. London, Gale & Polden, 1905, p. 58-59

- Coetzee & Eysturlid pp 117-18

- Markham pp. 256

- Markham pp. 257-58

- Markham pp. 259

- Motley pp. 426-27

- Watson, Robert (1792). The History of the Reign of Philip II. King of Spain, Volume 3. p. 253.

- Motley pp. 428-30

- Dunthorne p.50

- Manning p.56

- Graf von Bismarck, Friedrich Wilhelm; Beamish, North Ludlow (1855). On the Uses and Application of Cavalry in War: From the Text of Bismark, with Practical Examples Selected from Antient and Modern History. T. & W. Boone. pp. 328–29.

- Leon p. 93

Bibliography

- Dunthorne, Hugh (2013). Britain and the Dutch Revolt, 1560-1700. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521837477.

- Eysturlid, Lee W; Coetzee, Daniel, eds. (2013). Philosophers of War: The Evolution of History's Greatest Military Thinkers (2 Volumes). ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313070334.

- Fissel, Mark Charles (2001). English warfare, 1511–1642; Warfare and history. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21481-0.

- Gosman, Martin; Peeters, Joop W. Koopmans, eds. (2007). Selling and Rejecting Politics in Early Modern Europe Volume 25 of Groningen studies in cultural change. ISBN 9789042918764.

- Hadfield, Andrew; Hammond, Paul, eds. (2014). Shakespeare And Renaissance Europe, Arden Critical Companions. A&C Black. ISBN 9781408143698.

- Markham, Clement (2007). The Fighting Veres: Lives Of Sir Francis Vere And Sir Horace Vere. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1432549053.

- Van der Hoeven, Marco (1997). Exercise of arms: warfare in the Netherlands, 1568-1648. New York: BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10727-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- León, Fernando González de (2009). The Road to Rocroi: Class, Culture and Command in the Spanish Army of Flanders, 1567-1659 Volume 52 of History of warfare. BRILL. ISBN 9789004170827.

- Manning, Roger B (2006). An Apprenticeship in Arms: The Origins of the British Army 1585-1702. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780199261499.

- Nolan, Cathal J (2006). The Age of Wars of Religion, 1000-1650: An Encyclopaedia of Global Warfare and Civilization, Volume 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313337345.

- Van Nimwegen, Olaf (2010). The Dutch Army and the Military Revolutions, 1588-1688. New York: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84383-575-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weigley, Rusell Frank (2004). The Age of Battles: The Quest for Decisive Warfare from Breitenfeld to Waterloo. Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-21707-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

.jpg)