Battle of Herbsthausen

The Battle of Herbsthausen, also known as the Battle of Mergentheim, took place near Bad Mergentheim, in the modern German state of Baden-Württemberg. Fought on 2 May 1645, during the Thirty Years War, it featured a French army led by Turenne, and a Bavarian force under Franz von Mercy.

| Battle of Herbsthausen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Thirty Years' War | |||||||

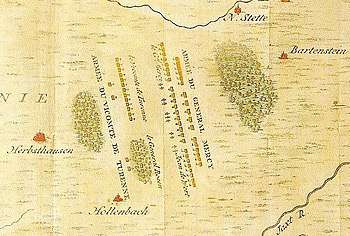

Battle of Mergentheim (“Mariendal” in the drawing), or Battle of Herbsthausen, of 1645. Plan of action, French depiction. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Vicomte de Turenne | Franz von Mercy | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

3500 infantry 5500 cavalry |

4300 infantry 5300 cavalry 9 guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2600 killed[2] 59 standards[3] | 500 killed[3] | ||||||

In February, 5,000 Bavarian cavalry were detached to support the Imperial army in Bohemia, most of whom were lost in the defeat at Jankau on 6 March. Mercy avoided Turenne until he had assembled enough troops, and surprised him at Herbsthausen on 5 May. The battle was short, as the inexperienced French infantry dissolved, and over 4,500 prisoners were taken.

In August, Mercy was killed at Second Nördlingen, where both sides suffered casualties of over 4,000 each. Although fighting continued, a military solution was no longer possible, and increased the urgency of negotiations that led to the 1648 Peace of Westphalia.

Background

The Thirty Years War began in 1618 when the Protestant dominated Bohemian Estates offered the Crown of Bohemia to fellow Protestant Frederick of the Palatinate, rather than conservative Catholic Emperor Ferdinand II. Most members of the Holy Roman Empire remained neutral, and the revolt was quickly suppressed. An army of the Catholic League, dominated by Bavarians, then invaded the Palatinate and sent Frederick into exile.[4]

His replacement by the Catholic Maximilian of Bavaria changed the nature and extent of the war. It drew in Protestant German states like Saxony and Brandenburg-Prussia, as well as external powers like Denmark-Norway. In 1630, Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden invaded Pomerania, partly to support his Protestant co-religionists, but also to control the Baltic trade, which provided much of Sweden's income.[5]

Economic factors meant Swedish intervention continued after Gustavus was killed in 1632, but conflicted with states within the Empire, like Saxony, and regional rivals, such as Denmark. Most of Sweden's German allies made peace in the 1635 Treaty of Prague. The war lost its religious nature, and turned into a contest between the Empire and Sweden, supported by France and George Rákóczi, Prince of Transylvania.[6]

Ferdinand III, who succeeded his father in 1637, agreed to peace talks in 1643, but ordered his diplomats to delay, hoping for a military solution.[7] However, in 1644 the Swedes defeated the Danes, who re-entered the war as an Imperial ally, then destroyed an Imperial army in Saxony. Despite victory at Freiburg in August 1644, the Bavarians under Franz von Mercy were unable to prevent the French capturing Philippsburg, and occupying Lorraine. Mercy withdrew into Franconia, and established winter quarters at Heilbronn.[8]

In 1645, Swedish commander Lennart Torstensson proposed a three part attack on Vienna, to compel Ferdinand III to agree terms. While the French advanced into Bavaria, Rákóczi would join forces with the Swedes in Bohemia, who would then move against Vienna. Mercy sent 5,000 veteran Bavarian cavalry under Johann von Werth to reinforce the Imperial army in Bohemia, which was heavily defeated at Jankau on 6 March.[9]

Armies of this period relied on foraging, both for men and the draught animals essential for transport, and cavalry; by 1645, the countryside was devastated by years of constant warfare, and units spent much of their time finding supplies. This limited operations and materially impacted the battle, since Turenne had widely distributed his army in order to support themselves. Of his 9,000 soldiers, 3,000 never made it onto the battlefield, while many others arrived too late to influence the outcome.

Battle

Victory at Jankau seemed an opportunity to knock Bavaria out of the war, and French chief minister Cardinal Mazarin ordered Turenne to bring the Bavarians to battle. Mercy evaded him, until he had more troops and after a month of counter-marching, the French were exhausted and short of supplies; in mid-April, Turenne halted, and distributed his army between Rothenburg and Bad Mergentheim. Here he awaited reinforcements from Hesse-Kassel, a French ally; most of the veteran French infantry had been lost at Freiburg, and Turenne did not yet trust his new recruits.[10]

Although only 1,500 of Werth's 5,000 cavalry returned from Bohemia, Mercy gathered 9,650 men and nine guns at Feuchtwangen, and matched north on 2 May. By the evening of the 4th, they were two kilometres from Herbsthausen, a small village south-east of Bad Mergentheim. They made contact with French cavalry patrols under Rosen around 2:00 am; Turenne ordered Rosen to position his cavalry on the right, while Schmidberg assembled the infantry along the edge of a wood overlooking the main road.[11]

Taken by surprise, Turenne was unable to deploy his guns, while 3,000 of the 9,000 troops in the area did not arrive at all. The Bavarian artillery opened fire, splinters and branches from the trees increasing its effectiveness, and Mercy ordered a general advance. As was common with inexperienced troops, the French infantry opened fire at too great a distance, and dissolved in panic. Turenne led a cavalry charge that scattered Werth's veterans, and fought his way out with 150 others, reaching Hanau in Hesse-Kassel. The infantry was forced to surrender, along with the garrison at Mergentheim, and 1,500 cavalry; Rosen and Schmidberg were among the roughly 4,500 prisoners.[12]

Aftermath

Most modern descriptions suggest Turenne was simply taken by surprise, but many nineteenth century French writers blamed Rosen for the defeat.[12] Turenne arrested Rosen in 1647 for mutiny, only releasing him after 14 months, while he has been described as a better 'soldier than general.'[13]

While victory restored Imperial morale after Jankau, it left the strategic position largely unchanged. Condé, victor of Rocroi, assumed command, and by early July had some 23,000 men.[14] Mercy returned to Heilbronn, where he received 4,500 men from Ferdinand of Cologne, bringing his army up to 16,000. The Bavarian once again demonstrated his ability to out manoeuvre his opponents, but on 3 August, he was killed at Second Nördlingen.[15]

Although considered a French victory, both sides lost over 4,000 men, casualties that shocked the French court, and by the end of the year, Turenne was back where he started. The Swedes had also been forced to retreat from Bohemia, but in September, John George of Saxony agreed a six month truce.[16] Ferdinand accepted a military solution was no longer possible, and in October, instructed his representatives at Westphalia to begin serious negotiations.[17]

References

- Ripley, George and Dana, Charles Anderson. The American Cyclopaedia. New York, 1874, p. 250. "...the standard of France was white, sprinkled with golden fleur de lis..."

- Barthold, Friedrich Wilhelm (1826). Johann von Werth im nächsten Zusammenhange mit der Zeitgeschichte. Leipzig.

- Schreiber, Friedrich Anton Wilhelm (1868). Maximilian I. der Katholische. Munich.

- Spielvogel 2006, p. 447.

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 385-386.

- Setton 1991, pp. 80-81.

- Höbelt 2012, p. 143.

- Wilson 2009, pp. 682-683.

- Wilson 2009, pp. 693-695.

- De Périni 1898, p. 69.

- De Périni 1898, pp. 70-71.

- De Périni 1898, p. 72.

- Poten 1889, pp. 197-199.

- De Périni 1898, p. 74.

- Bonney 2002, p. 64.

- Wilson 2009, p. 704.

- Wilson 2009, p. 716.

Sources

- Bonney, Richard (2002). The Thirty Years War 1618-1648. Osprey Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- De Périni, Hardÿ (1898). Batailles françaises, Volume IV. Ernest Flammarion, Paris.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Höbelt, Lothar (2012). Afflerbach, Holger; Strachan, Hew (eds.). Surrender in the Thirty Years War in How Fighting Ends: A History of Surrender. OUP. ISBN 978-0199693627.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Poten, Bernhard von (1889). Rosen, Reinhold von. Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie 29.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1991). Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0871691927.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spielvogel, Jackson (2006). Western Civilization (2014 ed.). Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 978-1285436401.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, Peter (2009). Europe's Tragedy: A History of the Thirty Years War. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0713995923.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)