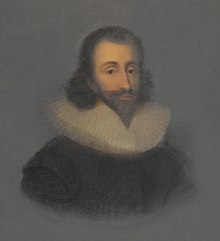

John Hampden

John Hampden (c. June 1595 – 24 June 1643) was an English landowner and politician whose opposition to arbitrary taxes imposed by Charles I made him a national figure. An ally of Parliamentary leader John Pym, and cousin to Oliver Cromwell, he was one of the Five Members whose attempted arrest in January 1642 sparked the First English Civil War.

John Hampden | |

|---|---|

John Hampden | |

| Committee of Safety | |

| In office July 1642 – June 1643 † | |

| Monarch | Charles I |

| Member of Parliament for Buckinghamshire | |

| In office November 1640 – December 1643 † | |

| Member of Parliament for Wendover | |

| In office 1628–1629 | |

| Member of Parliament for Grampound | |

| In office 1621–1622 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | circa June 1595 London |

| Died | 24 June 1643 (aged 48) Thame |

| Cause of death | Died of wounds |

| Resting place | Great Hampden church |

| Nationality | English |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Symeon (1619-1631) Letitia Knollys (1640-1643) |

| Relations | Oliver Cromwell; |

| Children | Richard (1631-1695); |

| Parents | William Hampden (1570-1597); Elizabeth Cromwell (1574-1664); |

| Alma mater | Magdalen College, Oxford |

| Occupation | Landowner and politician |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Infantry |

| Years of service | 1642 to 1643 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | Hampden’s Regiment of Foot |

| Battles/wars | First English Civil War Edgehill; Aylesbury; Brentford; Reading; Chalgrove Field; [1] |

After war began in August 1642, Hampden raised an infantry regiment, and died of wounds received at the Battle of Chalgrove Field on 18 June 1643. His loss was considered a serious blow, largely because he was one of the few Parliamentary leaders able to hold the different factions together.

His death in 1643 meant he avoided the bitter internal debates later in the war, the execution of Charles I in 1649, and establishment of The Protectorate. As a result, he is considered a less complex figure than either Cromwell, or even Pym; in 1841, his statue was erected in the Palace of Westminster, to represent the Parliamentary cause.[lower-alpha 1]

A reputation for honest, principled, and patriotic opposition to arbitrary rule also made him a popular figure in North America. Prior to the 1774 American Revolution, Franklin and Adams were among those who referenced him to justify their cause.[2]

Biographical

John Hampden was born around June 1595, probably in London, eldest son of William Hampden, (1570-1597), and Elizabeth Cromwell, (1574-1664).[3]

The Hampden family had been established in Buckinghamshire for many years; William was a lawyer, and Member of Parliament for East Looe in 1593.[4] When he died in April 1597, his cousin, William Hampden of Ennington, was appointed executor, but became involved in a bitter legal dispute with Elizabeth. William's estates were inherited by John's younger brother, Richard (1596-1659).[5]

In 1619, he married Elizabeth Symeon, a substantial heiress, although her father outlived both his daughter, and son-in-law. Prior to her death in 1631, they had nine children, of whom seven survived into adulthood; Ann (1616-1701), Elizabeth (1619-1643), John (1621-1642), William (died 1675), Ruth (1628-1687), Mary (1630-1689), and Richard (1631-1695), who became Chancellor of the Exchequer under William III.[6] In 1640, he married Letitia Knollys (1591-1666); they had no children before he died in 1643.

Career

1610 to 1629; Political activism

In 1610, he graduated from Magdalen College, Oxford; as legal training was then considered part of a gentleman's education, he attended the Inner Temple from 1613 to 1615.[3]

While in London, he became closely involved with other Puritans, a general term for anyone who wanted to reform, or 'purify', the Church of England. It covered a variety of doctrines, of which Calvinists such as Hampden were the most prominent, connecting him to a network that included Sir Richard Knightley, Lord Saye, and John Preston.[3]

In 1621, Hampden was elected Member of Parliament for Grampound, a rotten borough in Cornwall. This is thought to have been through the influence of the local magnate, John Arundell; a good example of the complexity of the period, Arundell opposed Ship Money in 1636, but held Pendennis Castle for Charles I until 1646.[7]

He financed a campaign to restore Parliamentary representation to Wendover in 1624, a seat he held until 1629. As MP for Wendover, he sat in the 1626 Parliament, subsequently known as the 'Useless Parliament', as it failed to pass any legislation. In return for approving taxes, Parliament insisted on impeaching the Duke of Buckingham, a military commander notorious for inefficiency, and extravagance. Rather than comply, Charles dissolved it.[8]

Instead of taxes, he imposed a forced loan and over 70 individuals were jailed for refusing to pay, including Hampden's cousin, Sir Edmund Hampden.[9] When Hampden also declined to subscribe, he was arrested; while in prison, he met Sir John Eliot, who led the Petition of Right campaign in 1628. The consequent reduction of income from the loans obliged Charles to call a new Parliament in March 1627. This returned "a preponderance of MPs opposed to the King", including Selden, Coke, John Pym and a young Oliver Cromwell.[9]

Released to attend Parliament, Hampden was closely involved in its efforts to limit the king's power, the first being adoption of the Petition of Right in June 1628. This opened the way to a new impeachment of Buckingham, which ended when he was assassinated in August by a disgruntled soldier. The next issue was that of Roger Maynwaring and Robert Sibthorpe, two priests who published sermons supportive of supporting the divine right of kings, passive obedience, and implying Charles did not need Parliament's approval to raise taxes.[3]

In the 17th century, religion and politics were considered interdependent; 'good government' required 'true religion'; this meant alterations in one implied alterations in the other.[lower-alpha 2] The two priests took a general belief in divine right, then used it to justify taxes, which was inflammatory enough in itself. [11] Maynwaring's claim those who disobeyed the king risked eternal damnation caused fury among Calvinists.[lower-alpha 3] The suggestion 'kings were gods' was also regarded as blasphemy.[12] Censured for preaching against the established constitution, they were later pardoned by Charles, who dismissed Parliament in 1629, and instituted eleven years of Personal Rule.[13]

1630 to 1639; Ship Money

Hampden's role in the 1628 Parliament was largely behind the scenes, where his organisational and man-management skills could be best used, but placed him in the inner circle of Parliamentary opposition. In 1629, the Earl of Warwick granted him lands in Saybrook Colony, now Old Saybrook, Connecticut; participation in the colonial movement was common among Puritan leaders. Other participants included Pym, who was treasurer of the Providence Island Company, Warwick, Lord Saye, Knightley, Henry Darley, William Waller, and Lord Brooke.[14] Company meetings provided cover to organise political opposition; whether its members also considered permanent emigration is still disputed.[15]

Hampden remained a relatively obscure figure, until 1637, when he was prosecuted in a test case to confirm the legality of Ship Money. This was a long-standing levy, raised in coastal counties to fund the Royal Navy, but only in time of war, not every year as Charles was now doing. Opposition was based on the principle of taxes imposed without Parliamentary approval, not the tax itself; there was widespread support for a powerful navy to protect English trade.[3]

Its extension into inland counties like Hampden's estates in Buckinghamshire widened opposition to its collection, and how it was spent. HMS Sovereign of the Seas, a 100 gun warship built between 1634 to 1637, was a prestige project five times the cost of normal ships, too large for any English harbour.[16] Finally, rather than using it to deter Charles used it to transport Spanish bullion and supplies to Flanders for their war against the Protestant Dutch, payment for which he kept.[17]

The Parliamentary leaders, including Hampden, owned multiple properties, and to make it clear they only opposed its legality, they were careful to pay some assessments. Hampden was tried by the Court of Exchequer in June 1637, but divisions among the judges delayed their ruling until July 1638. Although seven out of the twelve found the tax legal, the fact five did not made it a public relations disaster for Charles; less than 20% of the £208,000 assessed for 1639 was paid. Many refused demands for 'Coat and conduct' money during the 1639 and 1640 Bishops' Wars, fearing if they did, Charles would turn them into permanent taxes.[18]

1640 to July 1642; the road to civil war

Following defeat in the first of the Bishops Wars, Charles recalled Parliament in April 1640; when the Short Parliament refused to vote taxes without concessions, he dissolved it after only three weeks. However, the humiliating terms imposed by the Scots after a second victory in 1640 forced him to hold fresh elections in November; Pym acted as unofficial leader of the opposition, with Hampden co-ordinating the different factions.[19]

Shortly after the Long Parliament assembled, it was presented with the Root and Branch petition; signed by 15,000 Londoners, it demanded England follow the Scots, and expel bishops from the Church of England.[20] This reflected widespread concerns about 'Catholic practices', or Arminianism in the Church of England, given weight by Charles' apparent willingness to make war on the Protestant Scots, but not assist his nephew Charles Louis regain his hereditary lands.[lower-alpha 4] Many feared Charles was about to sign an alliance with Spain, a view shared by experienced diplomatic observers like Venice, and even France.[21]

This meant ending Charles' arbitrary rule was not only important for England, but the Protestant cause in general. Respect for the institution of monarchy prevented direct attacks on Charles, and instead meant prosecuting his 'evil counsellors.' These showed that even if the king was above the law, his subordinates were not, and he could not protect them; the intention was to make others think twice about their actions. Laud was impeached in December 1640, and held in the Tower of London;[lower-alpha 5] in May 1641, the Earl of Strafford, former Lord Deputy of Ireland and organiser of the 1640 Bishops War, was executed.[8]

The Commons also passed a series of constitutional reforms, including the Triennial Acts, abolition of the Star Chamber, and an end to levying taxes without Parliament's consent. Voting as a block, the bishops ensured all these were rejected by the Lords.[22] In June 1641, Parliament responded with the Bishops Exclusion Bill, which was rejected by the Lords. The outbreak of the Irish Rebellion in October brought matters to a head; both Charles and Parliament supported raising troops to suppress it, but neither trusted the other with their control.[23]

The Grand Remonstrance was presented to Charles on 1 December 1641; unrest culminated in 23 to 29 December with widespread riots in Westminster, led by the London apprentices. Suggestions Parliamentary leaders helped organise these have not been proved, but it prevented bishops attending the Lords.[24] On 30 December, John Williams, Archbishop of York and eleven other bishops, signed a complaint, disputing the legality of any laws passed by the Lords during their exclusion. This was viewed by the Commons as inviting the king to dissolve Parliament; all twelve were arrested.[25]

Hampden was among the Five Members that Charles attempted to arrest in January; after it failed, he left London, accompanied by many Royalist MPs, and members of the Lords. This was a major tactical mistake, as it gave his opponents majorities in both houses.[26] However, even at this late stage, the vast majority on both sides wanted to avoid civil war, and petitioned Parliament and Charles to agree terms.[27]

Pym and Hampden were among the few to understand only military victory could compel Charles to keep his commitments. He openly told foreign ambassadors any concessions were temporary, and would be retrieved by force if needed, an approach confirmed by the Scottish experience. The Irish Catholic rebels claimed approval for their actions; while untrue, the assertion was given weight by his attempts to use Irish troops against the Scots, and initial refusal to condemn the rebellion.[28]

However, regardless of religion or political belief, in 1642 the vast majority believed a 'well-ordered' monarchy was divinely mandated; where they disagreed was what 'well-ordered' meant, and who held ultimate authority in clerical affairs.[29] Since Charles could not be deposed, the only way of dealing with him was through military victory; it was this clarity that set Hampden, Pym, and later Oliver Cromwell apart from the majority. When the First English Civil War began, Hampden was appointed to the Committee of Safety.

August 1642 to June 1643; War and death

When war began in August 1642, both sides expected it to be settled by a single, decisive battle; many areas remained neutral, while awaiting the result. Hampden raised a regiment, which acted as baggage escort at Edgehill in October; one of the companies was commanded by his eldest son John, who was killed. After the disastrous Battle of Brentford, he helped rally troops for the defence of London. However, his main contribution was holding the Parliamentary factions together over the first winter, and preparing for a long war by initiating the negotiations that led to the Solemn League and Covenant with the Scots in August 1643.[3]

When the 1643 campaign began, Hampden was serving with the Earl of Essex, whose lack of aggression was already causing concern. Tasked with taking the Royalist war capital of Oxford, Essex captured Reading on 27 April, where he remained until mid May. On 18 June 1643, Hampden was wounded at the Battle of Chalgrove Field; shot twice in the shoulder, the wound became infected. Later claims these injuries were caused by the explosion of his own pistol have not been substantiated.[30]

He died at home six days later, and was buried in Great Hampden church. Unlike Pym, who died of cancer in December, his loss was mourned on both sides of the conflict; his close friend Anthony Nicholl wrote ‘Never Kingdom received a greater loss in one subject, never a man a truer and more faithful friend.’[31] In 1843, George Nugent-Grenville, a Whig radical politician and author of the hagiographic Memorials of John Hampden, paid for the Hampden Monument, located near the battle site.[32]

Legacy

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Hampden was used as an example of how rebellion against the state could be reconciled with patriotism, particularly as his death in battle allowed him to be positioned as a martyr to the cause of liberty. Prior to the 1774 American Revolution, Franklin and Adams were among those who used him to justify their cause.[2]

The early 19th century British radical movement set up Hampden Clubs, while he was referenced by Radical poet Percy Shelley. In Mary Shelley's novel, Frankenstein, he appears as a symbol of rebellion against patriarchal authority.[33]

When the Palace of Westminster was rebuilt after 1834, he was selected as one of the famous Parliamentary figures whose statues are positioned in St Stephen's Hall.[34][lower-alpha 6] In the early 20th century, the Suffragette movement used him to justify their slogan of 'No vote, no tax', and even today he is used by anti-tax resisters.[lower-alpha 7]

He was a less complex figure than either Pym, or his cousin Oliver Cromwell, while his death in 1643 meant he avoided the bitter internal debates later in the war, the execution of Charles in 1649, and establishment of The Protectorate.[lower-alpha 8] In reality, he and Pym were closely aligned; both recognised far earlier than most Charles had to be defeated militarily, but Hampden rarely made speeches, and was far less visible. In his 'History of the Rebellion', Clarendon claimed his influence and reputation derived from his man management skills and ability to organise.[36]

.jpg)

A variety of establishments bear his name, in Britain, and other parts of the English-speaking world, notably the United States; these include schools, towns, counties, hospitals, and geographical points. His enduring popularity as a symbol of Parliamentary freedom continues; in 2012, Mount Hampden was selected as the location for the new Zimbawean Parliament, which is under construction.[37]

Other examples include the World War II Handley Page Hampden bomber; the Hampden electric locomotive used on the London Underground Metropolitan line until 1961, and is now on display in the London Transport Museum.[38] In addition, there are two Masonic lodges named after him; Lodge 6290, in Oxfordshire,[39] and 6483 in Buckinghamshire.[40]

Hampden is the namesake of Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia, founded in 1775.

Notes

- The Royalist chosen was another moderate, Viscount Falkland, killed at Newbury three months later.

- Summarised by Hampden in the debate on the Petition of Right; "Here is 1, an innovation of religion suspected; is it not high time to take it to heart and acquaint his Majesty? 2ly, alteration of government; can you forbear when it goes no less than the subversion of the whole state? 3ly, hemmed in with enemies; is it now a time to be silent, and not to show to his Majesty that a man that has so much power uses none of it to help us? If he be no papist, papists are friends and kindred to him."[10]

- A key Calvinist concept was belief in Predestination, and salvation through faith alone.

- A perspective summarised by Francis Rous in 1641; "For Arminianism is the span of a Papist, and if you mark it well, you shall see an Arminian reaching to a Papist, a Papist to a Jesuit, a Jesuit to the Pope, and the other to the King of Spain. And having kindled fire in our neighbours, they now seek to set on flame this kingdom also."

- He was not executed until 1645

- Others include Charles James Fox and William Pitt

- Although they generally miss the point he objected to the process, not the taxes themselves

- Illustrated in Thomas Gray's poem "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard"; "Some village-Hampden, that with dauntless breast / The little tyrant of his fields withstood;....Cromwell guiltless of his country's blood."[35]

References

- BCW Project.

- Jansson 2009, pp. 11-12.

- Russell 2008.

- WJJ 1981.

- Thompson 2010.

- "John Hampden". Geni.com. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Duffin & Hunneyball 2010.

- Ferris & Hunneyball 2010.

- Hostettler 1997, p. 127.

- Keeler & Janssen Cole 1997, pp. 121-122.

- Pyle 2000, pp. 562-563.

- Barry 2012, p. 72.

- Little 2008, p. 33.

- Duinen 2007, p. 531.

- Young 1984, p. 195.

- Berckman 1974, p. 79.

- Harris 2014, pp. 295-296.

- Harris 2014, pp. 297-298.

- Jessup 2013, p. 25.

- Rees 2016, p. 2.

- Wedgwood 1955, p. 248.

- Rees 2016, pp. 7–8.

- Hutton 2003, p. 4.

- Smith 1979, pp. 315–317.

- Rees 2016, pp. 9–10.

- Manganiello 2004, p. 60.

- Hutton 2003, pp. 3-5.

- Wedgwood 1958, pp. 26–27.

- Macloed 2009, pp. 5–19 passim.

- Lester & Blackshaw 2000, pp. 21-24.

- Adair 1979, p. 17.

- Historic England 1059742.

- Crawford 1988, pp. 250-253.

- St Stephens Hall.

- Gray 1825, p. 120.

- Clarendon 1704, p. 278.

- Mushanawani.

- Green, Graham 1988, p. 44.

- "Hampden Lodge No. 6290".

- "Hampden Lodge No. 6483".

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Hampden. |

- "Colonel John Hampden's Regiment of Foot". BCW Project. Retrieved 8 April 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Adair, John (1979). "The Death of John Hampden". History Today. 29 (10).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barry, John M (2012). Roger Williams and the Creation of the American Soul: Church, State, and the Birth of Liberty. Viking Press. ISBN 978-0670023059.

- Berckman, Evelyn (1974). Creators and Destroyers of the English Navy. Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0241890349.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clarendon, Earl of (1704). The History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England; Volume III (2019 ed.). Wentworth Press. ISBN 978-0469445765.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crawford, Ian (1988). "Wading through slaughter: John Hampden, Thomas Gary, and Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein"". Studies in the Novel. 20 (3). JSTOR 29532578.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duffin, Anne; Hunneyball, Paul (2010). ARUNDELL, John (1576-1654), of Trerice, Newlyn, Cornw in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1604–1629 (Online ed.). CUP. ISBN 978-1107002258.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gray, Thomas (1825). The Works of Thomas Gray, Containing His Poems and Correspondence: With Memoirs of His Life and Writings, Volume 1. Harding, Triphook, and Lepard.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Green, Oliver; Graham, Benjamin (1988). London's Underground: The Story of the Tube (2019 ed.). White Lion Publishing. ISBN 978-0711240131.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harris, Tim (2014). Rebellion: Britain's First Stuart Kings, 1567-1642 (Kindle ed.). OUP. ISBN 978-0199209002.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hostettler, John (1997). Sir Edward Coke: A Force for Freedom (2006 ed.). Universal Law Publishing Co Ltd. ISBN 978-8175345690.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hutton, Ronald (2003). The Royalist War Effort 1642-1646. Routledge. ISBN 9780415305402.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jansson, Maija (2009). "Shared Memory: John Hampden, New World and Old". British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies. 32 (2): 157–171. doi:10.1111/j.1754-0208.2008.00106.x.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jessup, Frank W. (2013). Background to the English Civil War: The Commonwealth and International Library: History Division. Elsevier. ISBN 9781483181073.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keeler, Mary Frear; Janssen Cole, Maija (1997). Proceedings in Parliament, 1628, Volume 4, (Yale Proceedings in Parliament). University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1580460095.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lester, Derek; Blackshaw, Gill (2000). The Controversy of John Hampden’s Death. Chalgrove Battle Group. ISBN 978-0953803408.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Historic England. "Hampden Monument (Grade II) (1059742)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 April 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Manganiello, Stephen (2004). The Concise Encyclopedia of the Revolutions and Wars of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1639–1660. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810851009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mushanawani, Cletus (20 December 2019). "Mt Hampden City taking shape". The Herald. Retrieved 30 April 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pyle, Andrew (2000). The Dictionary of Seventeenth-century British Philosophers, Volume I. Thoemmes Continuum. ISBN 978-1855067042.

- Russell, Conrad (2008). "Hampden, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12169.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Rees, John (2016). The Leveller Revolution. Verso. ISBN 978-1784783907.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Steven (1979). "Almost Revolutionaries: The London Apprentices during the Civil Wars". Huntington Library Quarterly. 42 (4). JSTOR 3817210.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "St Stephens Hall". Parliament. Retrieved 30 April 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, Christopher (2010). HAMPDEN, Richard (1596-1659/60), of Great Hampden, Bucks. and Emmington, Oxon in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1604–1629 (Online ed.). CUP. ISBN 978-1107002258.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- WJJ (1981). HAMPDEN, William (1570-97), of Great Hampden, Bucks in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1558–1603 (Online ed.). CUP. ISBN 978-1107002258.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Young, Alfred A (1984). English Plebeian Culture in 18th Century American Radicalism in ' "The Origin of Anglo-American Radicalism (1991 ed.). Humanities Press International Inc.,U.S. ISBN 978-0391037038.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Parliament of England | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir Francis Barnham Thomas St Aubyn |

Member of Parliament for Grampound 1621–1622 With: Sir Robert Carey |

Succeeded by John Mohun Sir Richard Edgecumbe |

| Preceded by Franchise resumed |

Member of Parliament for Wendover 1624–1629 With: Alexander Denton 1624 Richard Hampden 1625 Sampson Darrell 1626 Ralph Hawtree 1628–1629 |

Succeeded by Parliament suspended until 1640 |

| Preceded by Parliament suspended since 1629 |

Member of Parliament for Buckinghamshire 1640–1643 With: Arthur Goodwin |

Succeeded by George Fleetwood Edmund West |