Standing rigging

Standing rigging comprises the fixed lines, wires, or rods, which support each mast or bowsprit on a sailing vessel and reinforce those spars against wind loads transferred from the sails. This term is used in contrast to running rigging, which represents the moveable elements of rigging which adjust the position and shape of the sails.[1]

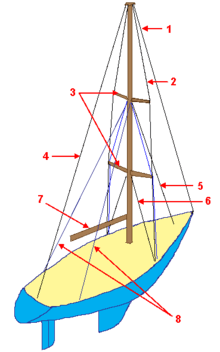

Key: 1. Forestay 2. Shroud 3. (Spreaders) 4. Backstay 5. Inner forestay 6. Sidestay 7. (Boom) 8. Running backstays

Historical development

Early sailing vessels used rope of hemp or other fibers,[2] which gave way to wire ropes of various types. Galvanized steel was common for the first half of the 20th century, continuing as an inexpensive option to its 1960s successor material—stainless steel cables and rods. In the late 20th Century, racing yachts adopted composite fiber lines for standing rigging, with the goal of reducing weight and windage aloft.[3]

Materials

On modern yachts, standing rigging is often stainless steel wire, Nitronic-50 stainless steel rod or synthetic fiber. Semi-rigid stainless steel wire is by far the most common as it combines extreme strength, relative ease of assembling and rigging with reliability. Unlike rigid stainless steel rod, it is comparatively easy to recognize wear and stress as individual strands (normally 19) break often near a swage fitting, and can be inspected while standing.[3] Solid rod stainless steel is more aerodynamic so is often used in extreme racing yachts but it is difficult to see stress as this requires profesional inspection such as dye penetrate testing or x-raying.[4] Rod rigging is strongest when terminated with a cold head rather than swage fittings. This process requires a different, expensive machine but yields a more durable end fitting. Rod-type stays fail suddenly, often where the rod bends around a spreader. Bending can induce unseen stress fractures.[5]

Fore-and-aft rigged vessels

Most fore-and-aft rigged vessels have the following types of standing rigging: a forestay, a backstay, and upper and lower shrouds (side stays). Less common rigging configurations are diamond stays and jumpers. Both of these are used to keep a thin mast in column especially under the load of a large down wind sail or in strong wind. Rigging parts include swageless terminals, swage terminals, shackle toggle terminals and fail-safe wire rigging insulators.[3]

Square-rigged vessels

Whereas 20th-Century square-rigged vessels were constructed of steel with steel standing rigging, prior vessels used wood masts with hemp-fiber standing rigging. As rigs became taller by the end of the 19th Century, masts relied more heavily on successive spars, stepped one atop the other to form the whole, from bottom to top: the lower mast, top mast, and topgallant mast. This construction relied heavily on support by a complex array of stays and shrouds. Each stay in either the fore-and-aft or athwartships direction had a corresponding one in the opposite direction providing counter-tension. Fore-and-aft the system of tensioning started with the stays that were anchored in front each mast. Shrouds were tensioned by pairs of deadeyes, circular blocks that had the large-diameter line run around them, whilst multiple holes allowed smaller line—lanyard—to pass multiple times between the two and thereby allow tensioning of the shroud.[6]

Lateral support

In addition to overlapping the mast below, the top mast and topgallant mast were supported laterally by shrouds that connected to either a platform, called a "top", or cross-wise beams, called "crosstrees", and anchored futtock shrouds from below that led to the lower mast.[6]

Fore-and-aft support

Each additional mast segment was supported fore and aft by a series of stays that led forward. These lines were countered in tension by backstays, which were secured along the sides of the vessel behind the shrouds.[6]

References

- Keegan, John (1989). The Price of Admiralty. New York: Viking. p. 280. ISBN 0-670-81416-4.

- Hedderwick, Peter (1830). A treatise on marine architecture: containing the theory and practice of shipbuilding, with rules for the proportions of masts, rigging, weight of anchors, &c. Edinburgh: For the Author. p. 401.

- Westerhuis, Rene (2013). Skipper's Mast and Rigging Guide. Adlard Coles Nautical. London: Bloomsbury. p. 5. ISBN 9781472901491.

- "Care and Maintenance". NavtecRiggingSolutions.com. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

-

Hood, Jeremy R. (1997). Safety Preparations for Cruising. Sheridan House, Inc. pp. 272. ISBN 9781574090222.

standing rigging.

- zu Mondfeld, Wolfram (2005). Historic Ship Models. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 352. ISBN 9781402721861.