Barapa Barapa

The Barapa Barapa people (also known as Baraparapa) are an indigenous Australian people whose territory covered parts of southern New South Wales and northern Victoria. They had close connections with the Wemba-Wemba.

Barapa Barapa have extensive shared country with their traditional neighbours, the Wemba-Wemba and Yorta Yorta, covering Deniliquin, the Kow Swamp and Perrricoota/Koondrook. The Barapa Barapa form part of the North-West Nations Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Group, and undertake significant cultural heritage and Natural Resource Management work in the area.

Language

R. H. Mathews wrote an early sketch of the grammar of the Barapa Barapa language, and stated that one dialect at least existed, spoken on the Murray River near Swan Hill.[1]

Country

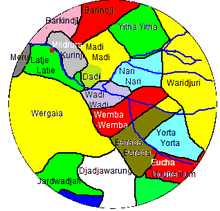

Baraparapa territory which covered areas in what are now the states of New South Wales and Victoria, is estimated to have taken in some 3,600 square miles (9,300 km2) of land, southern tributaries of the Murrumbidgee River from above Hay down to Kerang. One early source also has them, perhaps a distinct horde, present in Moulamein[lower-alpha 1] It included Cohuna, Gunbower, Brassi, Conargo, and the land south of Carrathool.[2] Deniliquin Their neighbours to the north west were the Wemba-Wemba, the Wergaia frontier was directly to the west, the Yorta Yorta boundaries ran north and south to their east. The Djadjawurrung lay to the south.

Social organization

The Barapabarapa hordes had a moiety (kin ship) moiety society divided into two phratries, each comprising two sections. The rules of marriage and affiliation are as follows.[lower-alpha 2]

- Phratry A:

- (a) a Murri man marries an Ippatha woman. Their sons are Umbi, daughters Butha.

- (b) a Kubbi man marries a Butha woman. Their sons are Ippai, daughters Ippatha.

- Phratry B

- (a) An Ippai man marries a Matha woman. Their sons are Kubbi, daughters Kubbitha.

- (b) An Umbi man marries a Kubbitha woman. Their sons are Murri, daughters Matha.[lower-alpha 3]

In terms of initiation ceremonies, the Barapabarapa rites were essentially the same as those prevailing among the Wiradjuri.[3]

Lifestyle

The Barapa Barapa were one of the Murray River Wongal-chewing groups: [4] wangul bulrushes were chewed both for the tuberous pith and for the fibrous cortex which was torn away to obtain the latter. The fibre was conserved to make strings for fashioning nets and bags.[4][5]

History

A mortar in Barapa barapa territory, at Koondrook Perricoota Forest near Barbers Creek, was recovered in 2012 and an analysis led to the suggestion that it might have been employed to grind gypsum, used by more northerly tribes in funerals, but here perhaps for obtaining a corroboree body paint.[6]

Alternative names

Some words

- bangga (a boy)

- barapa (no)

- dyelli-dyellic (yesterday)

- gillaty (today)

- kurregurk (a girl)

- lêurk (a woman)

- ngungni (yes)

- perbur (tormorrow)

- wutthu (a man)

Source: Mathews 1904, pp. 291,293

Notes

- R. H. Mathews recorded some of their language from Informants in Moulamein. (Mathews 1904, p. 291)

- The terms, save for one and consonantal doubling are almost identical to those given for the Gamilaraay system by A. W. Howitt in 1884 (Palmer & Howitt 1884, p. 341)

- Exceptions exist, with a Murri marrying a Butha, or Kubbi an Ippatha. Strictly speaking, this diagram would imply a brother's child can marry his sister's child, but this is rigorously forbidden. A brother's child's offspring may marry a sister's child's offspring. (Mathews 1904, p. 294)

Citations

- Mathews 1904, pp. 291–294.

- Tindale 1974, pp. 191–192.

- Mathews 1904, p. 294.

- Pardoe 2012, p. 3.

- Gott 1982, p. 61.

- Pardoe 2013, pp. 5–7.

- Tindale 1974, p. 192.

- Weir et al. 2013, p. 4.

Sources

- "AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia". AIATSIS.

- Barwick, Diane E. (1984). McBryde, Isabel (ed.). "Mapping the past: an atlas of Victorian clans 1835-1904". Aboriginal History. 8 (2): 100–131. JSTOR 24045800.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beveridge, Peter (1883). "Of the aborigines inhabiting the great lacustrine and Riverine depression of the Lower Murray". Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales. Melbourne. 17: 19–74.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gott, Beth (April 1982). "Ecology of Root Use by the Aborigines of Southern Australia". Archaeology in Oceania. Melbourne. 17 (1): 59–67. JSTOR 40386580.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mathews, R. H. (1904). "The Wiradyuri and Other Languages of New South Wales". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 34: 284–305. JSTOR 2843103.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Palmer, Edward; Howitt, A. W. (1884). "Notes on Some Australian Tribes". Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 13: 276–347. JSTOR 2841896.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pardoe, Colin (April 2012). "Burials from Barber Overflow, Koondrook State Forest, NSW". The Joint Indigenous Group. pp. 1–13.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pardoe, Colin (2013). A Mortar from Perricoota State Forest. pp. 1–10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pardoe, Colin (April 2013). "Burials through the ages among the Barapa Barapa". The Joint Indigenous Group. pp. 1–5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Baraparapa (NSW)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weir, Jessica K; Ross, Steven L; Crew, David R. J.; Crew, Jeanette L (2013). Cultural water and the Edward/Kolety and Wakool river system (PDF). AIATSIS. ISBN 978-1-922-10206-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)