The Devils (film)

The Devils is a 1971 British historical drama film written and directed by Ken Russell and starring Oliver Reed and Vanessa Redgrave. The film is a dramatised historical account of the rise and fall of Urbain Grandier, a 17th-century Roman Catholic priest accused of witchcraft following the supposed possessions in Loudun, France; it also focuses on Sister Jeanne des Anges, a sexually repressed nun who inadvertently incites the accusations.

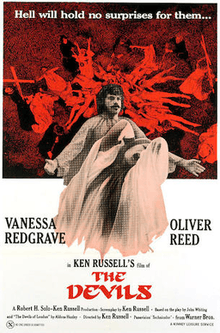

| The Devils | |

|---|---|

Original theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ken Russell |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by | Ken Russell |

| Based on | The Devils of Loudun by Aldous Huxley and The Devils by John Whiting |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Peter Maxwell Davies |

| Cinematography | David Watkin |

| Edited by | Michael Bradsell |

Production company | Russo Productions |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 111 minutes[lower-alpha 1] |

| Country |

|

| Language | English |

| Box office | ~ US$11 million[1] |

A co-production between the United Kingdom and the United States, The Devils was partly adapted from the 1952 non-fiction book The Devils of Loudun by Aldous Huxley, and partly from the 1960 play The Devils by John Whiting, also based on Huxley's book. United Artists originally pitched the idea to Russell but abandoned the project after reading his finished screenplay, as they felt it was too controversial in nature. Warner Bros. subsequently agreed to produce and distribute the film. The majority of principal photography took place at Pinewood Studios in late 1970.

The film faced harsh reaction from national film rating systems due to its disturbingly violent, sexual, and religious content, and originally received an X rating in both the United Kingdom and the United States. It was banned in several countries, and eventually heavily edited for release in others. The film has never received a release in its original, uncut form in various countries. Critics similarly dismissed the film for its explicit content, though it won the awards for Best Director at the Venice Film Festival, as well as from the U.S. National Board of Review.

Film scholarship on The Devils has largely focused on its themes of sexual repression and abuse of power. It has also been recognized as one of the most controversial films of all time by numerous publications and film critics. The film remained banned in Finland until 2001.

Plot

In 17th-century France, Cardinal Richelieu is influencing Louis XIII in an attempt to gain further power. He convinces Louis that the fortifications of cities throughout France should be demolished to prevent Protestants from uprising. Louis agrees, but forbids Richelieu from carrying out demolitions in the town of Loudun, having made a promise to its Governor not to damage the town.

Meanwhile, in Loudun, the Governor has died, leaving control of the city to Urbain Grandier, a dissolute and proud but popular and well-regarded priest. He is having an affair with a relative of Father Canon Jean Mignon, another priest in the town; Grandier is, however, unaware that the neurotic, hunchbacked Sister Jeanne des Anges (a victim of severe scoliosis who happens to be abbess of the local Ursuline convent), is sexually obsessed with him. Sister Jeanne asks for Grandier to become the convent's new confessor. Grandier secretly marries another woman, Madeleine De Brou, but news of this reaches Sister Jeanne, driving her to jealous insanity. When Madeleine returns a book by Ursuline foundress Angela Merici that Sister Jeanne had earlier lent her, the abbess viciously attacks her with accusations of being a "fornicator" and "sacrilegious bitch," among other things.

Baron Jean de Laubardemont arrives with orders to demolish the city, overriding Grandier's orders to stop. Grandier summons the town's soldiers and forces Laubardemont to back down pending the arrival of an order for the demolition from King Louis. Grandier departs Loudun to visit the King. In the meantime, Sister Jeanne is informed by Father Mignon that he is to be their new confessor. She informs him of Grandier's marriage and affairs, and also inadvertently accuses Grandier of witchcraft and of possessing her, information that Mignon relays to Laubardemont. In the process, the information is pared down to just the claim that Grandier has bewitched the convent and has dealt with the Devil. With Grandier away from Loudon, Laubardemont and Mignon decide to find evidence against him.

Laubardemont summons the lunatic inquisitor Father Pierre Barre, a "professional witch-hunter," whose interrogations actually involve depraved acts of "exorcism", including the forced administration of enemas to his victims. Sister Jeanne claims that Grandier has bewitched her, and the other nuns do the same. A public exorcism erupts in the town, in which the nuns remove their clothes and enter a state of "religious" frenzy. Duke Henri de Condé (actually King Louis in disguise) arrives, claiming to be carrying a holy relic which can exorcise the "devils" possessing the nuns. Father Barre then proceeds to use the relic in "exorcising" the nuns, who then appear as though they have been cured – until Condé/Louis reveals the case allegedly containing the relic to be empty. Despite this, both the possessions and the exorcisms continue unabated, eventually descending into a massive orgy in the church in which the disrobed nuns remove the crucifix from above the high altar and sexually assault it.

In the midst of the chaos, Grandier and Madeleine return and are immediately arrested. After being given a ridiculous show trial, Grandier is shaven and tortured – although at his execution, he eventually manages to convince Mignon that he is innocent. The judges, clearly under orders from Laubardemont, sentence Grandier to death by burning at the stake. Laubardemont has also obtained permission to destroy the city's fortifications. Despite pressure on Grandier to confess to the trumped-up charges, he refuses, and is then taken to be burnt at the stake. His executioner promises to strangle him rather than let him suffer the agonising death by fire that he would otherwise experience, but the overzealous Barre starts the fire himself, and Mignon, now visibly panic-stricken about the possibility of Grandier's innocence, pulls the noose tight before it can be used to strangle the priest. As Grandier burns, Laubardemont gives the order for explosive charges to be set off and the city walls are blown up, causing the revelling townspeople to flee.

After the execution, Barre leaves Loudun to continue his witch-hunting activities elsewhere in the southwest of France. Laubardemont informs Sister Jeanne that Mignon has been put away in an asylum for claiming that Grandier was innocent (the explanation given is that he is demented), and that "with no signed confession to prove otherwise, everyone has the same opinion". He gives her Grandier's charred femur and leaves. Sister Jeanne, now completely broken, masturbates with the bone. Madeleine, having been released, walks over the rubble of Loudun's walls and away from the ruined city.

![]()

Cast

- Oliver Reed as Father Urbain Grandier

- Vanessa Redgrave as Sister Jeanne des Anges

- Dudley Sutton as the Baron de Laubardemont

- Max Adrian as Ibert

- Gemma Jones as Madeleine de Brou

- Murray Melvin as Father-Canon Jean Mignon

- Michael Gothard as Father Pierre Barre

- Georgina Hale as Philippe Trincant

- Brian Murphy as Adam

- John Woodvine as Louis Trincant

- Christopher Logue as Cardinal Richelieu

- Kenneth Colley as Legrand

- Graham Armitage as Louis XIII of France

- Andrew Faulds as Rangier

- Judith Paris as Sister Agnes[lower-alpha 2]

- Catherine Willmer as Sister Catherine

Analysis

Film scholar Thomas Atkins attests that, while The Devils contains overt themes regarding religion and political influence, the film is in fact more concerned with "sex and sexual aberrations."[3] He interprets the film as being centrally thematically interested in sexual repression and its cumulative effects on the human psyche.[4] Commenting on the Sister Jeanne character, Atkins writes: "There are any number of examples of tormented visualization involving the Mother Superior... What more stunning visual metaphor for the psychological suffocation of the Mother Superior than to stuff her deformed body into a tiny lookout space from which she watches her fantasy lover? The mere confinement of mass in congested space creates an understanding of the annihilating pleasures of her sexual drive."[5] Atkins likens Sister Jeanne's erotic fantasy sequences to "eroticism from a deranged consciousness."[6]

The color white is used significantly in the film, specifically in the design of the cityscape, which is overtly white and consists of stone structures.[5] Atkins insists that through this use of blank white, Russell establishes a "leitmotif of whiteness which resists and dissolves natural relationships."[5]

Production

Development

After the success of Russell's Women in Love (1969) in the United States, its distributor, United Artists, suggested that Russell adapt Aldous Huxley's The Devils of Loudun (1952), a non-fiction book concerning the alleged 17th-century possessions in Loudun, France.[7] Russell wrote the screenplay based on Huxley's novel, as well as John Whiting's 1961 play The Devils, which itself was based on Huxley's work.[8] Russell said "when I first read the story, I was knocked out by it — it was just so shocking—and I wanted others to be knocked out by it, too. I felt I had to make it."[9] Russell later said at the time he made the film: "I was a devout Catholic and very secure in my faith. I knew I wasn't making a pornographic film... although I am not a political creature, I always viewed The Devils as my one political film. To me it was about brainwashing, about the state taking over."[9] Though Russell admired Whiting's play, he mainly drew from Huxley's book as he found the play "too sentimental."[1]

Some extraneous elements incorporated into the screenplay were not found in either source, including details about the plague, which were supplied by Russell's brother-in-law, a scholar of French history.[1] Upon studying Grandier, Russell felt that he "represented the paradox of the Catholic church... Grandier is a priest but he is also a man, and that puts him into some absurd situations."[10] In Russell's original screenplay, the role of Sister Jeanne of the Angels, the disabled Mother Superior, was significantly larger, and continued after Grandier's execution.[11] However, in order to shorten the lengthy screenplay, Russell was forced to cut down the role.[11]

United Artists announced the film in August 1969, with Robert Sole to produce under a three picture deal with the studio, and Russell to direct.[1] Filming was set to start in May 1970.[12] However, after United Artists executives read the screenplay, they "refused to touch it," abandoning plans to fund the production.[9] At the time, production designer Derek Jarman had already constructed some of the sets for the film.[13] It was subsequently acquired by Warner Bros.,[9] who signed on in March 1970 to distribute the film.[1]

Casting

.jpg)

Oliver Reed, who had worked with Russell previously on Women in Love, was cast as Urbain Grandier, the philandering doomed priest.[14] Richard Johnson, who had portrayed Grandier in a stage production of The Devils, had originally been attached to the project in 1969, but eventually dropped out of the production.[1] Reed agreed to do the film for a percentage of the profits.[15] Gemma Jones was cast as Madeleine de Brou, Grandier's mistress.[16] Sister Jeanne des Anges was originally to be played by Glenda Jackson, who had starred opposite Reed in Russell's Women in Love, as well as in Russell's The Music Lovers.[1][11] However, Jackson turned down the role saying: "I don't want to play any more neurotic sex starved parts."[17] Russell later claimed that he felt Jackson had actually turned down the role because it had been truncated from his original screenplay.[11] Jackson was replaced by Vanessa Redgrave.[18]

Max Adrian was cast as inquisitor Ibert (in his second-to-last film performance),[19] while Dudley Sutton, who had become a cult figure for his performance in The Leather Boys (1964), agreed to appear in the film as Baron de Laubardemont.[20] Sutton recalled that all of the "respectable actors turned it down. They thought it was blasphemous, which it is not."[20] In the role of Father Mignon, a priest who attempts to usurp Grandier's power, Russell cast Murray Melvin, despite the fact that he was decades younger than the character, who was intended to be in his eighties.[21] Michael Gothard, an English character actor, was cast as self-professed witch hunter Father Barre.[2] Russell cast Christopher Logue, a sometimes-actor who was mainly known as a poet and literary scholar, as the vengeful Cardinal Richelieu.[22]

As Phillipe, the young woman Grandier impregnates, Russell cast television actress Georgina Hale.[22] Judith Paris, originally a dancer, was cast as Sister Agnes, Richelieu's niece who enters the convent under the guise of becoming a nun in order to gather information on Sister Jeanne.[2] In the credits, her role is mislabeled as "Sister Judith."[2]

Filming

Filming began 17 August 1970[14] in London at Pinewood Studios.[1] The film's sets of Loudun—which were depicted as a modernistic white-tiled city— were devised by Jarman, who spent a total of three months designing them.[23] In conceiving the look of the city, Russell was influenced by the cityscape in Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1927).[24] The interiors of many of the buildings, specifically the convent, were crafted with plaster and made to appear as masonry; the plaster designs were then nailed to plywood framework.[25]

Director Russell hired a large cast of extras, whom he later referred to as "a bad bunch" who were demanding and entitled, and alleged that one of the female extras appearing as a civilian was sexually assaulted by another male extra.[26] Jones recalled that Reed, who at the time had a reputation for being disruptive and confrontational, was extremely kind to her on set, and "behaved impeccably."[16] Sutton recalled of Redgrave that she was "always an adventurous type of person" on the set, in terms of exploring her character and interacting with the other performers.[27] Russell echoed this sentiment, referring to Redgrave as "one of the least bothersome actresses I could ever wish for; she just threw herself into it."[28]

Additional photography occurred at Bamburgh Castle in Northumberland, England.[1] Jones recalled filming at the castle as challenging due to cold weather and having the flu during this period of the shoot, to which Russell was "frightfully unsympathetic."[28] Throughout the shoot, Russell and Reed clashed frequently, and by the time principal photography had finished, the two were hardly on speaking terms.[29]

Soundtrack

The film score was composed for a small ensemble by Peter Maxwell Davies.[30] Russell was reportedly intrigued by Davies' 1969 composition Eight Songs for a Mad King. Davies reportedly took the job because he was interested in the late medieval and Renaissance historical period depicted in the film.[31] He went on to write a score for Russell's next film, The Boyfriend. The Australian promoter James Murdoch, who was also Davies' agent, was involved in organising the music for both these films.

The score recorded by Davies' regular collaborators the Fires of London with extra players as the score calls for more than their basic line-up.[32] Maxwell Davies' music is complemented by period music (including a couple of numbers from Terpsichore), performed by the Early Music Consort of London under the direction of David Munrow.[33]

Release

Box office

The film was one of the most popular movies in 1972 at the British box office.[36] The film grossed approximately $8–9 million in Europe, and an additional $2 million in the United States, making for a worldwide total gross of around $11 million.[1]

Critical response

The Devils received significant critical backlash upon its release due to its "outrageous," "overheated," and "pornographic" nature.[37] The film was publicly condemned by the Vatican, who, though acknowledging that it contained some artistic merit, asked that its screenings at the Venice Film Festival be cancelled.[38] Judith Crist called the film a "grand fiesta for sadists and perverts",[37] while Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film a rare zero-star rating.[39] Pauline Kael wrote of the film in The New Yorker that Rusell "doesn't report hysteria, he markets it."[40] Vincent Canby, writing for The New York Times, noted that the film contains "silly, melodramatic effects," and felt that the performances were hindered by the nature of the screenplay, writing: "Oliver Reed suggests some recognizable humanity as poor Father Grandier, but everyone else is ridiculous. Vanessa Redgrave, who can be, I think, a fine actress, plays Sister Jeanne with a plastic hump, a Hansel-and-Gretel giggle, and so much sibilance that when she says "Satan is ever ready to seduce us with sensual delights," you might think that Groucho Marx had let the air out of her tires."[41]

Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times lambasted the film, writing that its message is "not anti-clerical—there's hardly enough clericalism to be anti anymore—it is anti-humanity. A rage against cruelty has become a celebration of it... you weep not for the evils and the ignorance of the past, but for the cleverness and sickness of the day."[42] Ann Guarino of the New York Daily News noted that the film "could not be more anti-Catholic in tone or more sensationalized in treatment," but conceded that the performances in the film were competent.[43] The Ottawa Citizen's Gordon Stoneham similarly felt the film had been over-sensationalized, noting that Russell focuses so much on the "baroque effects, and concentrates so much on the Grand Guignol aspects of the affair, the narrative is never firmly in focus."[44]

Bridget Byrne of the LA Weekly alternately praised the film as "brilliant, audacious, and grotesque," likening it to a fairytale, but added that audiences "have to grasp its philosophy, work out the undercurrents of seriousness, close the structural gaps for [themselves], even as [they] are transported by a literal orgy of splendor."[45] Writing for the Hackensack, New Jersey Record, John Crittenden praised the film's visuals as "genius," but criticized Reed's performance while asserting that Redgrave was underused.[46] Stephen Farber of The New York Times noted the film as an ambitious work, conceding that the "ideas in Russell's film may seem overly schematic, but his terrifying, fantastical nightmare images have astonishing psychological power."[47]

On internet review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, The Devils holds an approval rating of 67%, based on 30 reviews, and an average rating of 7.32/10. Its consensus reads, "Grimly stylish, Ken Russell's baroque opus is both provocative and persuasive in its contention that the greatest blasphemy is the leveraging of faith for power."[48] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 49 out of 100, based on 11 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[49]

Accolades

| Institution | Category | Recipient | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Board of Review | Best Director | Ken Russell | Won | [1] |

| Venice Film Festival | Best Director – Foreign | Won | [50] |

Censorship

The explicit sexual and violent content, paired with its commentary on religious institutions, resulted in the film suffering significant censorship.[1][51] Commenting on the film's controversial nature, Reed stated: "We never set out to make a pretty Christian film. Charlton Heston made enough of those... The film is about twisted people."[52] The British Board of Film Censors found the film's combination of religious themes and violent sexual imagery a serious challenge, particularly as the Board was being lobbied by socially conservative pressure groups such as the Festival of Light at the time of its distribution.[53] In order to gain a release and earn a British 'X' certificate (suitable for those aged 18 and over), Russell made minor cuts[54] to the more explicit nudity (mainly in the cathedral and convent sequences), details from the first exorcism (mainly that which indicated an anal insertion), some shots of the crushing of Grandier's legs, and a pantomime sequence during the climactic burning.[55] Russell later said:

Trevelyan's objections to my original cut were that the scenes of torture—such as the skewering of Grandier’s tongue with needles, or the breaking of his knees—simply went on too long. To him, these scenes needed only a few frames to tell the audience what was happening; after that, the sounds and their imaginations would fill in the rest. With the exception of one sequence ("The Rape of Christ”) which was removed in its entirety, all Trevelyan did was to tone down or reduce the scenes as I had cut them.[56]

–Russell on the film's controversial content[57]

The most significant cuts were made by Warner Bros. studios, prior to submission to the BBFC. Two notable scenes were removed in their entirety: One was a two-and-a-half-minute sequence featuring naked nuns sexually defiling a statue of Christ, which includes Father Mignon looking down on the scene and masturbating.[58] Another scene near the end of the film showed Sister Jeanne masturbating with the charred femur of Grandier after he is burned at the stake.[59] Because of its content, the former scene has been popularly referred to as the "Rape of Christ" sequence.[60][61]

The British theatrical cut, which runs 111 minutes, was given an 'X' certificate (no one under 18 years of age admitted) in the United Kingdom.[62] In the United States, the film was truncated even further for theatrical release: The Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) cut it to approximately 108 minutes, and also awarded it an 'X' rating.[1] Russell expressed frustration with the censorship of the film, commenting that they “killed the key scene” [the Rape of Christ] and that "Warner Brothers cut out the best of The Devils."[1] Speaking on the American version of the film, Russell stated that the cuts made "adversely affected the story, to the point where in America the film is disjointed and incomprehensible."[63]

The extended version of the film (running approximately 117 minutes) with the aforementioned footage restored, was screened for the first time in London on 25 November 2002, along with a making-of documentary titled Hell on Earth, produced for Channel 4.[60] The extended version was procured by Mark Kermode, who uncovered the footage in the Warner Bros. vaults.[61] The film remained banned in Finland for over 40 years, until the ban was ultimately lifted in November 2011.[64]

Home media

The Devils has had a complicated release history in home media formats, with various cuts being made available in different formats.[65] Warner Home Video released a clamshell VHS of the film in the United States in 1983, labeled as featuring a 105-minute cut of the film;[66] however, this is a misprint, as this edition actually runs 103 minutes, due to time compression.[67] Warner reissued a VHS edition in 1995, with a corrected label of a 103-minute running time.[68] A VHS was issued in the United Kingdom by Warner in 2002 as part of their "Masters of the Movies" series, reportedly running 104 minutes.[69] However, according to film historian Richard Crouse, the VHS version available in the United Kingdom is identical to the American VHS editions, despite the labeled runtimes.[67]

A bootlegged NTSC-format DVD was released by Angel Digital in 2005, with the excised footage reinstated, along with the Hell on Earth documentary included as a bonus feature.[70] In 2008, it was suspected that Warner Home Video may have been planning a U.S. DVD release for the film, as cover artwork was leaked on the internet.[71] However, Warner responded to the claim by deeming the leaked news an "error."[71] In June 2010, Warner released The Devils in a 108-minute version for purchase and rental through the iTunes Store,[72] but the title was removed without explanation three days later.[73]

On 19 March 2012, the British Film Institute released a 2-disc DVD featuring the 111-minute UK theatrical version (sped up to 107 minutes to accommodate the technicalities of PAL colour).[71][74] The BFI release also includes the Kermode documentary Hell on Earth, as well as a vintage documentary shot during the production entitled Directing Devils, among other features[74]

In March 2017, streaming service Shudder began carrying the 109-minute U.S. release version of The Devils.[75] As of 2019, it is available for screening via Shudder.[76] In September 2018, FilmStruck began streaming the same U.S. cut and it was subsequently added to the Criterion Channel in October 2019, almost a year after FilmStruck shut down.[77]

Legacy

The Devils has been cited as one of the most controversial films of all time,[78] named by such critics as Richard Crouse, among others.[79] FilmSite included it in their list of the 100 most controversial films ever made,[80] and in 2015, Time Out magazine ranked it 47 on their list of the "50 Most Controversial Movies in History."[81]

Film historian Joel W. Finler described The Devils as Russell's "most brilliant cinematic achievement, but widely regarded as his most distasteful and offensive work."[82] In 2002, when 100 film makers and critics were asked to cite what they considered to be the ten most important films ever made, The Devils featured in the lists submitted by critic Mark Kermode and director Alex Cox.[83] In 2014, Mexican filmmaker Guillermo del Toro publicly criticized Warner Bros. for censoring the film and limiting its availability in home video markets.[84]

See also

- Mother Joan of the Angels – A 1961 Polish film also based on the Loudun possessions.

- The Crucible, ostensibly about Salem witch trials, but actually a political satire that shares several plot parallels with The Devils.

- The Devils of Loudun (opera) by Krzysztof Penderecki, 1968 and 1969; revisions 1972 and 1975.

- Belladonna of Sadness

Notes and references

Notes

References

- "The Devils". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Los Angeles, California: American Film Institute. Archived from the original on 4 November 2019.

- Crouse 2012, p. 63.

- Atkins 1976, p. 55.

- Atkins 1976, p. 59.

- Atkins 1976, p. 58.

- Atkins 1976, p. 64.

- Baxter 1973, pp. 182–183.

- Crouse 2012, p. 33.

- Kermode 1996, p. 53.

- Baxter 1973, p. 204.

- Crouse 2012, p. 59.

- "Huxley Drama to Be Film". The New York Times. New York City, New York. 19 August 1969. p. 18.

- Baxter 1973, p. 201.

- "Stars Signed for 'The Devils'". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. 19 June 1970. p. 15 – via Newspapers.com.

- Reed 1979, p. 135.

- Crouse 2012, p. 58.

- Toynbee, Polly (28 February 1971). "A Queen without vanity". The Observer. London, England. p. 3.

- Crouse 2012, p. 60.

- Crouse 2012, p. 65.

- Crouse 2012, p. 64.

- Crouse 2012, p. 66.

- Crouse 2012, p. 67.

- Crouse 2012, p. 75.

- Baxter 1973, p. 207.

- Baxter 1973, p. 206.

- Baxter 1973, pp. 208–209.

- Crouse 2012, p. 61.

- Crouse 2012, p. 88.

- Crouse 2012, p. 118.

- Crouse 2012, p. 81.

- Crouse 2012, pp. 81–2.

- Crouse 2012, p. 83.

- "The Devils: composer's note". maxopus.com. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- "Prom 40". BBC. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017.

- Hewett, Ivan (4 December 2012). "H7steria, BBC Concert Orchestra, Queen Elizabeth Hall, review". The Telegraph. London, England. Archived from the original on 27 December 2017.

- Harper 2011, p. 269.

- Hanke 1984, p. 118.

- "Vatican Assails Film on Priests, Orgies in Convent". The Des Moines Register. Des Moines, Iowa. Associated Press. 31 August 1975 – via Newspapers.com.

- Ebert, Roger (1971). "The Devils". Chicago Sun-Times. Chicago, Illinois. Archived from the original on 4 October 2019.

- Crouse 2012, p. 157.

- Canby, Vincent (17 July 1971). "' The Devils,' an Adaptation With Fantasy:Work by Ken Russell Opens at Fine Arts Miss Redgrave in Role of Sister Jeanne". The New York Times. New York City, New York. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019.

- Champlin, Charles (16 July 1971). "The Games 'Devils' Plays". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. p. 57 – via Newspapers.com.

- Guarino, Ann (17 July 1971). "Ken Russell's 'Devils' Is Anti-Religious Film". New York Daily News. New York City, New York. p. 47 – via Newspapers.com.

- Stoneham, Gordon (13 October 1971). "The Devils bizarre film but fascinating". Ottawa Citizen. Ottawa, Ontario. p. 91 – via Newspapers.com.

- Byrne, Bridget (21 July 1971). "Russell's 'Devils': Brilliant, Audacious, and Grotesque". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. p. 15 – via Newspapers.com.

- Crittenden, John (19 July 1971). "A Devil's Brew of Garish Sex". The Record. Hackensack, New Jersey. p. 17D – via Newspapers.com.

- Farber, Stephen (15 August 1971). "'The Devils' Finds An Advocate". The New York Times. New York City, New York. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019.

- "The Devils (1971)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- "The Devils reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Kemp, Stuart (28 November 2011). "British Director Ken Russell Dies at 84". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 28 December 2011.

- Wells, Jeffrey (29 March 2010). "A History of Censorship". Hollywood Elsewhere. Archived from the original on 25 June 2010. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- Kramer, Carol (22 August 1971). "Oliver Burns—at the Stake and at Film Critics". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. p. E3 – via Newspaprs.com.

- Robertson 1993, pp. 139–146.

- Crouse 2012, p. 131.

- Crouse 2012, pp. 169–70.

- Kermode 1996, p. 54.

- Baxter 1973, p. 202.

- Baxter 1973, p. 210.

- Savlov, Marc (22 September 2019). "Burn, Witch, Burn". Austin Chronicle. Austin, Texas. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016.

- Lister, David (20 November 2002). "Russell's 'rape of Christ' to be shown". The Independent. London, England. Archived from the original on 4 November 2019.

- Gibbons, Fiachra (19 November 2002). "Cut sequence from The Devils discovered". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015.

- Crouse 2012, pp. 123, 130–31.

- Kermode 1996, p. 55.

- "Devils, The". Elonet (in Finnish). Helsinki, Finland: National Audiovisual Institute. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018.

- Crouse 2012, pp. 163–164.

- The Devils (VHS). Warner Home Video. 1983. 11110.

- Crouse 2012, p. 164.

- The Devils (VHS). Warner Home Video. 1995. ASIN 6300268918.CS1 maint: ASIN uses ISBN (link)

- The Devils (VHS). Warner Home Video. 2002. ASIN B00004CIPH.

- Crouse 2012, p. 173.

- Jahnke, Adam (4 October 2012). "Devils, The". The Digital Bits. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012.

- Gibron, Bill (24 August 2010). "Like Touching the Dead: Ken Russell's 'The Devils' (1971)". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019.

- Crouse 2012, p. 175.

- "DVD & Blu-ray: The Devils". BFI Filmstore. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012.

- Rife, Katie (15 March 2017). "Ken Russell's widely banned The Devils makes a surprise appearance on Shudder". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018.

- "The Devils". Shudder. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "Coming Attractions: The Criterion Channel's October 2019 Lineup". The Criterion Collection. 30 September 2019. Archived from the original on 4 November 2019.

- Dry, Jude (15 March 2017). "'The Devils': Ken Russell's Banned 1971 Religious Horror Film Finally Gets Streaming Release". IndieWire. Archived from the original on 25 April 2018.

- Grey, Tobias (25 September 2012). "Raising Hell". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 13 September 2013.

- "The 100+ Most Controversial Films of All-Time: 1970-1971". FilmSite. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018.

- Uhlich, Keith; Rothkopf, Joshua; Ehrlich, David; Fear, David (12 August 2015). "The 50 most controversial movies ever made". Time Out. New York. Archived from the original on 25 July 2016.

- Finler 1985, p. 240.

- "Sight and Sound Top Ten Poll 2002 – Who voted for which film: The Devils". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017.

- Vlessing, Etan (25 November 2014). "Guillermo del Toro Slams Warner Bros. for Censoring Ken Russell's 'The Devils'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018.

Sources

- Atkins, Thomas R., ed. (1976). Ken Russell. Monarch Film Studies. New York City, New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-08102-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baxter, John (1973). An Appalling Talent: Ken Russell. London, England: Joseph Pub. ISBN 978-0-71-811075-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crouse, Richard (2012). Raising Hell: Ken Russell and the Unmaking of the Devils. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-770-90281-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Finler, Joel W. (1985). The Movie Directors Story. London: Octopus Books. ISBN 978-0-706-42288-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanke, Ken (1984). Ken Russell's Films. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-810-81700-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harper, Sue (2011). British Film Culture in the 1970s: The Boundaries of Pleasure: The Boundaries of Pleasure. Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-748-65426-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kermode, Mark (1996). "The Devil Himself:Ken Russell". Video Watchdog. No. 35. pp. 53–58. ISSN 1070-9991.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lucas, Tim (1996). "Cutting the Hell out of the Devils". Video Watchdog. No. 35. ISSN 1070-9991.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reed, Oliver (1979). Reed All About Me. London, England: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-491-02039-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robertson, James Crighton (1993). The Hidden Cinema: British Film Censorship in Action, 1913–1975. New York City, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-09034-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)