Baby boomers

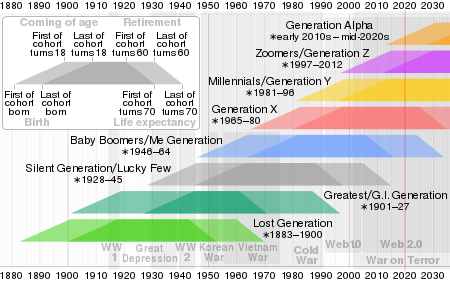

Baby boomers are the demographic cohort following the Silent Generation and preceding Generation X. The generation is generally defined as people born from 1946 to 1964, during the post–World War II baby boom.[1] The baby boom has been described variously as a "shockwave"[2] and as "the pig in the python."[3]

In the 1960s and 1970s, in the West, as this relatively large number of young people entered their teens and young adulthood—the oldest turned 18 in 1964—they, and those around them, created a very specific rhetoric around their cohort and the changes brought about by their size in numbers, such as the counterculture of the 1960s.[4] In China during the same period, the baby boomers lived through the Cultural Revolution and were subject to the one-child policy as adults.[5] This rhetoric had an important impact in the perceptions of the boomers, as well as society's increasingly common tendency to define the world in terms of generations, which was a relatively new phenomenon. In Europe and North America, many boomers came of age in a time of increasing affluence and widespread government subsidies in post-war housing and education,[2] and grew genuinely expecting the world to improve with time.[3]

| Part of a series on |

| Major generations of the Western world |

|---|

Timeline of major demographic cohorts since the late-nineteenth century with approximate dates and ages |

Etymology

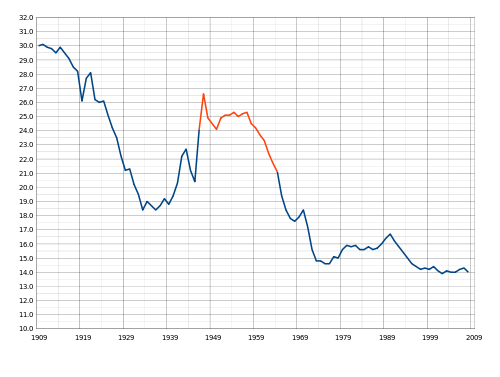

The term baby boom refers to a noticeable increase in the birth rate. The post-World War II population increase was described as a "boom" by various newspaper reporters, including Sylvia F. Porter in a column in the May 4, 1951, edition of the New York Post, based on the increase of 2,357,000 in the population of the U.S. in 1950.[6]

The first recorded use of "baby boomer" is in a January 1963 Daily Press article describing a massive surge of college enrollments approaching as the oldest boomers were coming of age.[7][8] The Oxford English Dictionary dates the modern meaning of the term to a January 23, 1970, article in The Washington Post.[9]

Date range and definitions

The Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary defines "baby boomer" as "a person born during a period of time in which there is a marked rise in a population's birthrate", "usually considered to be in the years from 1946 to 1964".[11] Pew Research Center defines baby boomers as being born between 1946 and 1964.[12] The United States Census Bureau defines baby boomers as "individuals born in the United States between mid-1946 and mid-1964."[13][14] The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics defines the "post-World War II baby-boom generation" as those born between 1946 and 1964,[15][16] as does the Federal Reserve Board which uses 1946–1964 to define baby boomers.[17] Gallup defines baby boomers as those born from 1946 through 1964.[18]

In the US, the generation can be segmented into two broadly defined cohorts: the "Leading-Edge Baby Boomers" are individuals born between 1946 and 1955, those who came of age during the Vietnam War era. This group represents slightly more than half of the generation, or roughly 38,002,000 people of all races. The other half of the generation, called the "Late Boomers" or "Trailing-Edge Boomers", was born between 1956 and 1964. This second cohort includes about 37,818,000 individuals, according to Live Births by Age and Mother and Race, 1933–98, published by the Centers for Disease Control's National Center for Health Statistics.[19]

In Australia, the Australian Bureau of Statistics defines baby boomers as those born between 1946 and 1964,[20] as well as the Australia's Social Research Center which defines baby boomers as born between 1946 and 1964.[21] Bernard Salt places the Australian baby boom between 1946 and 1961.[22][23]

Various authors have delimited the baby boom period differently. Landon Jones, in his book Great Expectations: America and the Baby Boom Generation (1980), defined the span of the baby-boom generation as extending from 1946 through 1964.[24] Authors William Strauss and Neil Howe, in their 1991 book Generations, define the social generation of boomers as that cohort born from 1943 to 1960, who were too young to have any personal memory of World War II, but old enough to remember the postwar American High before John F. Kennedy's assassination.[25] In Ontario, Canada, David Foot, author of Boom, Bust and Echo: Profiting from the Demographic Shift in the 21st century (1997), defined a Canadian boomer as someone born from 1947 to 1966, the years in which more than 400,000 babies were born. However, he acknowledges that that is a demographic definition, and that culturally, it may not be as clear-cut.[26]

Doug Owram argues that the Canadian boom took place from 1946 to 1962, but that culturally boomers everywhere were born between the late war years and about 1955 or 1956. He notes that those born in the years before the actual boom were often the most influential people among boomers: for example, musicians such as The Beatles, Bob Dylan, and The Rolling Stones, as well as writers like Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, who were either slightly or vastly older than the boomer generation. Those born in the 1960s might feel disconnected from the cultural identifiers of the earlier boomers.[27]

Generational cuspers

The American term "Generation Jones" is sometimes used to describe those born roughly between 1954 and 1965, on the cusp of boomers and Generation X.[28][29][30] Jonesers cite different life experiences from that of older boomers, having come of age in the 1970s instead of 1960s.[31][32][33]

Demographics

Asia

China's baby boom cohort is the largest in the world. According to journalist and photographer Howard French, who spent many years in China, many Chinese neighborhoods were, by the mid-2010s, disproportionately filled with the elderly, who the Chinese themselves referred to as a "lost generation" who grew up during the Cultural Revolution, when higher education was discouraged and large numbers of people were sent to the countryside for political reasons. As China's baby boomers retire in the late-2010s and onward, the people replacing in the workforce will be a much smaller cohort thanks to the one-child policy. Consequently, China's central government faces a stark economic trade-off between "cane and butter"—how much to spend on social welfare programs such as state pensions to support the elderly and how much to spend in the military to achieve the nation's geopolitical objectives.[5]

Europe

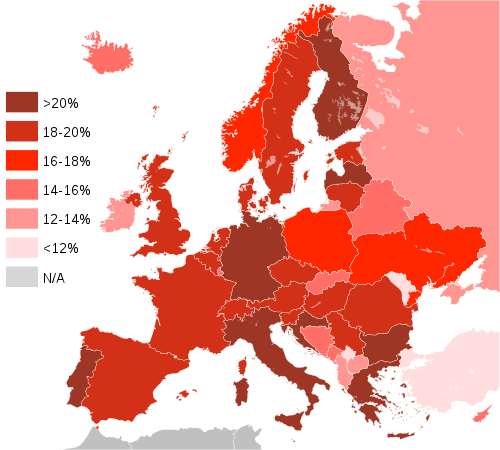

European countries by proportions of people aged 65 and over in 2018

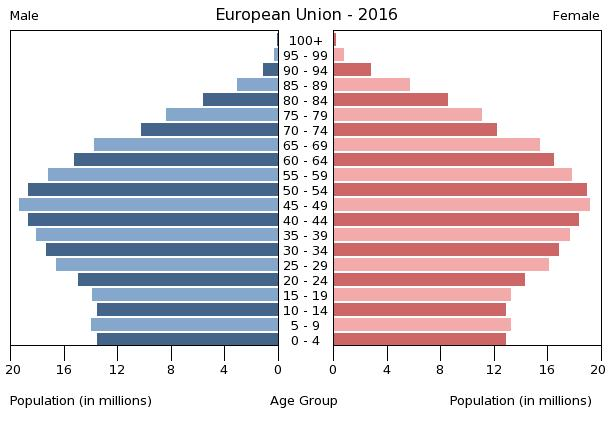

European countries by proportions of people aged 65 and over in 2018 Population pyramid of the European Union in 2016

Population pyramid of the European Union in 2016

From about 1750 to 1950, Western Europe transitioned from having both high birth and death rates to low birth and death rates. By the late 1960s or 1970s, the average woman had fewer than two children, and, although demographers at first expected a "correction," such a rebound never came. Despite a bump in the total fertility rates (TFR) of some European countries in the very late twentieth century (the 1980s and 1990s), especially France and Scandinavia, they never returned to replacement level; the bump was largely due to older women realizing their dreams of motherhood. Member states of the European Economic Community saw a steady increase in not just divorce and out-of-wedlock births between 1960 and 1985 but also falling fertility rates. In 1981, a survey of countries across the industrialized world found that while more than half of people aged 65 and over thought that women needed children to be fulfilled, only 35% of those between the ages of 15 to 24 (younger Baby Boomers and older Generation X) agreed. Falling fertility was due to urbanization and decreased infant mortality rates, which diminished the benefits and increased the costs of raising children. In other words, it became more economically sensible to invest more in fewer children, as economist Gary Becker argued. (This is the first demographic transition.) By the 1960s, people began moving from traditional and communal values towards more expressive and individualistic outlooks due to access to and aspiration of higher education, and to the spread of lifestyle values once practiced only by a tiny minority of cultural elites. (This is the second demographic transition.)[34]

At the start of the twenty-first century, Europe suffers from an aging population. This problem is especially acute in Eastern Europe, whereas in Western Europe, it is alleviated by international immigration.[35] Researches by the demographers and political scientists Eric Kaufmann, Roger Eatwell, and Matthew Goodwin suggest that such immigration-induced ethno-demographic change is one of the key reasons behind public backlash in the form of national populism across the rich liberal democracies, an example of which is the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum (Brexit).[36]

In 2018, 19.70% of the population the European Union as a whole was at least 65 years old.[37] The median age of all 28 members of the bloc, including the United Kingdom which recently decided to leave, was 43 years in 2019. It was about 29 in the 1950s, when there were just six members: Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. Like all other inhabited continents, Europe saw significant population growth in the late twentieth century. However, Europe's growth is projected to halt by the early 2020s due to falling fertility rates and an aging population. In 2015, a woman living in the European Union had on average 1.5 children, down from 2.6 in 1960. Although the E.U. continues to experience a net influx of immigrants, this is not enough to balance out the low fertility rates.[38] In 2017, the median age was 53.1 years in Monaco, 45 in Germany and Italy, 43 in Greece, Bulgaria, and Portugal, making them some of the oldest countries in the world besides Japan and Bermuda. They are followed by Austria, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia, and Spain, whose median age was 43.[39]

North America

Historically, the early Anglo-Protestant settlers in the sixteenth century were the most successful group, culturally, economically, and politically, and they maintained their dominance till the early twentieth century. Commitment to the ideals of the Enlightenment meant that they sought to assimilate newcomers from outside of the British Isles, but few were interested in adopting a pan-European identity for the nation, much less turning it into a global melting pot. But in the early 1900s, liberal progressives and modernists began promoting more inclusive ideals for what the national identity of the United States should be. While the more traditionalist segments of society continued to maintain their Anglo-Protestant ethnocultural traditions, universalism and cosmopolitanism started gaining favor among the elites. These ideals became institutionalized after the Second World War, and ethnic minorities started moving towards institutional parity with the once dominant Anglo-Protestants.[40] The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (also known as the Hart-Cellar Act), passed at the urging of President Lyndon B. Johnson, abolished national quotas for immigrants and replaced it with a system that admits a fixed number of persons per year based in qualities such as skills and the need for refuge. Immigration subsequently surged from elsewhere in North America (especially Canada and Mexico), Asia, Central America, and the West Indies.[41] By the mid-1980s, most immigrants originated from Asia and Latin America. Some were refugees from Vietnam, Cuba, Haiti, and other parts of the Americas while others came illegally by crossing the long and largely undefended U.S.-Mexican border. Although Congress offered amnesty to "undocumented immigrants" who had been in the country for a long time and attempted to penalize employers who recruited them, their influx continued. At the same time, the postwar baby boom and subsequently falling fertility rate seemed to jeopardize America's social security system as the Baby Boomers retire in the early twenty-first century.[42]

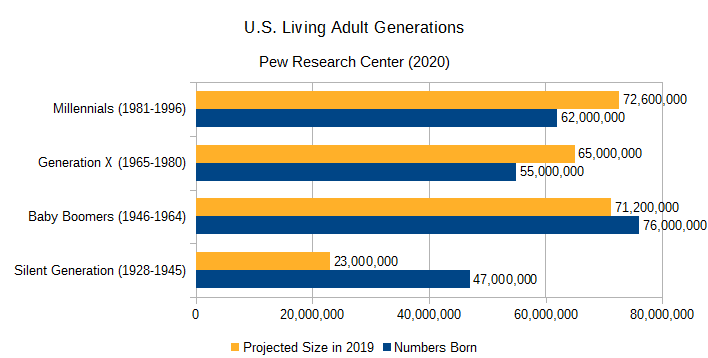

Using their own definition of baby boomers as people born between 1946 and 1964 and U.S. Census data, the Pew Research Center estimated there were 71.6 million boomers in the United States as of 2019.[43] The age wave theory suggests an economic slowdown when the boomers started retiring during 2007–2009.[44] Projections for the aging U.S. workforce suggest that by 2020, 25% of employees will be at least 55 years old.[45]

Characteristics

As children

In the West, baby boomers comprised the first generation to grow up with the television. Some popular boomer-era childhood shows of the 1950s and 1960s included Howdy Doody, The Mickey Mouse Club, I Love Lucy, Captain Video, Captain Kangaroo, Father Knows Best, Leave it to Beaver, Bonanza, The Soupy Sales Show, The Twilight Zone, The Andy Griffith Show, The Ed Sullivan Show, Gilligan's Island, The Addams Family, Bewitched, I Dream of Jeannie, Batman, and Star Trek.

As adolescents and young adults

As adolescents and young adults in the 1960s and 1970s, Western baby boomers found that the music they listened to and/or produced, most notably rock music (an outgrowth of Silent Generation-era rock and roll), was another expression of their generational identity. Transistor radios were personal devices that allowed boomer teenagers to listen to The Beatles, the Motown Sound, psychedelic rock, progressive rock, disco, early punk rock, and other new musical directions and artists.

Boomers grew up at a time of dramatic social change. In the U.S., that change marked the generation with a strong cultural cleavage, between the left-leaning proponents of change and the more conservative individuals. Analysts believe this cleavage has played out politically from the time of the Vietnam War to the present day,[46] to some extent defining the divided political landscape in the country.[47][48] Early boomers are often associated with the counterculture of the 1960s, the later years of the civil rights movement, and the "second-wave" feminist cause of the 1970s. Conversely, many trended in moderate to conservative directions opposite to the counterculture, especially those making professional careers in the military (officer and enlisted), law enforcement, business, blue collar trades, and Republican Party politics.[49][50]

Early boomers experienced events of the tumultuous 1960s like Beatlemania, Woodstock, organizing against or fighting in the Vietnam War, and the Apollo 11 moon landing, while late boomers (also known as Generation Jones) came of age in the "malaise era" of the 1970s with events such as the Watergate scandal, the 1973–1975 recession, the 1973 oil crisis, the United States Bicentennial, and the Iran hostage crisis. Politically, early boomers in the United States tend to be Democrats, while later boomers tend to be Republicans.[51]

In China, the baby boomers grew up during the Cultural Revolution, when institutions of higher learning were closed. As a consequence, when China introduced some elements of capitalist reforms in the late 1970s, most of this cohort found itself at a severe disadvantage as people were unable to take the various jobs that became vacant.[5]

In midlife

Economic power

Steve Gillon has suggested that one thing that sets the baby boomers apart from other generational groups is the fact that "almost from the time they were conceived, boomers were dissected, analyzed, and pitched to by modern marketers, who reinforced a sense of generational distinctiveness."[52]

This is supported by the articles of the late 1940s identifying the increasing number of babies as an economic boom, such as a 1948 Newsweek article whose title proclaimed "Babies Mean Business",[53] or a 1948 Time magazine article called "Baby Boom."[54]

From 1979–2007, those receiving the highest one percentile of incomes saw their already large incomes increase by 278% while those in the middle at the 40th–60th percentiles saw a 35% increase. Since 1980, after the vast majority of baby boomer college goers graduated, the cost of college has been increased by over 600% (inflation adjusted).[55]

After the Chinese Communist Party opened up their nation's economy in the late 1970s, because so many baby boomers did not have access to higher education, they were simply left behind as the Chinese economy grew enormously thanks to said reforms.[5]

Family values

According to American demographer Philip Longman, "even among baby boomers, those who wound up having children have turned out to be remarkably similar to their parents in their attitudes about 'family' values."[56] In the postwar era, most returning servicemen looked forward to "making a home and raising a family" with their wives and lovers, and for many men, family life was a source of fulfillment and a refuge from the stress of their careers. Life in the late 1940s and 1950s was centered about the family and the family was centered around children.[57]

Due to the one-child policy introduced in the late 1970s, one-child households have become the norm in China, leading to rapid population aging, especially in the cities where the costs of living are much higher than in the countryside.[58]

Attitude towards religion

In 1993, Time magazine reported on the religious affiliations of baby boomers. Citing Wade Clark Roof, a sociologist at the University of California at Santa Barbara, the articles stated that about 42% of baby boomers were dropouts from formal religion, 33% had never strayed from church, and 25% of boomers were returning to religious practice.

The boomers returning to religion were "usually less tied to tradition and less dependable as church members than the loyalists. They are also more liberal, which deepens rifts over issues like abortion and homosexuality."[59]

In retirement

A survey found that nearly a third of baby boomer multimillionaires polled in the US would prefer to pass on their inheritance to charities rather than pass it down to their children. Of these boomers, 57% believed it was important for each generation to earn their own money; 54% believed it was more important to invest in their children while they were growing up.[60]

As of 1998, it was reported that, as a generation, boomers had tended to avoid discussions and long-term planning for their demise.[61] However, since 1998 or earlier, there has been a growing dialogue on how to manage aging and end-of-life issues as the generation ages.[62]

In particular, a number of commentators have argued that baby boomers are in a state of denial regarding their own aging and death and are leaving an undue economic burden on their children for their retirement and care. According to the 2011 Associated Press and LifeGoesStrong.com surveys:

- 60% lost value in investments because of the economic crisis

- 42% are delaying retirement

- 25% claim they will never retire (currently still working)[63][64]

People often take it for granted that each succeeding generation will be "better off" than the one before it. When Generation X came along just after the boomers, they would be the first generation to enjoy a lower quality of life than the generation preceding it.[65][66]

The density of baby boomers can put a strain on Medicare. According to the American Medical Student Association, the population of individuals over the age of 65 will increase by 73 percent between 2010 and 2030, meaning one in five Americans will be a senior citizen.[67]

In 2019, advertising platform Criteo conducted a survey of 1,000 U.S. consumers which showed baby boomers are less likely than millennials to purchase groceries online. Of the baby boomers surveyed, 30 percent said they used some form of online grocery delivery service.[68]

By the mid-2010s, it has already become apparent that China was facing a serious demographic crisis as the population of retirees boomed while the number of working-age people shrank. This poses serious challenges for any attempts to implement social support for the elderly and imposes constraints on China's future economy prospects.[58]

Political views and participation

In Europe, the period between the middle to the late twentieth century could be described as an era of 'mass politics', meaning people were generally loyal to a chosen political party. Political debates were mostly about economic questions, such as wealth redistribution, taxation, jobs, and the role of government. But as countries transitioned from having industrial economies to a post-industrial and globalized world, and as the twentieth century became the twenty-first, topics of political discourse changed to other questions and polarization due to competing values intensified.[69]

But scholars such as Ronald Inglehart traced the roots of this new 'culture conflict' all the way back to the 1960s, which witnessed the emergence of the Baby Boomers, who were generally university-educated middle-class voters. Whereas their predecessors in the twentieth century – the Lost Generation, the Greatest Generation, and the Silent Generation – had to endure severe poverty and world wars, focused on economic stability or simple survival, the Baby Boomers benefited from an economically secure, if not affluent, upbringing and as such tended to be drawn to 'post-materialist' values. Major topics for political discussion at that time were things like the sexual revolution, civil rights, nuclear weaponry, ethnocultural diversity, environmental protection, European integration, and the concept of 'global citizenship'. Some mainstream parties, especially the social democrats, moved to the left in order to accommodate these voters. In the twenty-first century, supporters of post-materialism lined up behind causes such as LGBT rights, climate change, multiculturalism, and various political campaigns on social media. Inglehart called this the "Silent Revolution." But not everyone approved, giving rise to what Piero Ignazi called the "Silent Counter-Revolution."[69] The university-educated and non-degree holders have very different upbringing, live very different lives, and as such hold very different values.[70] Education plays a role in this 'culture conflict' as national populism appeals most strongly to those who finished high school but did not graduate from university while the experience of higher education has been shown to be linked to having a socially liberal mindset. Degree holders tend to favor tolerance, individual rights, and group identities whereas non-degree holders lean towards conformity, and maintaining order, customs, and traditions.[71] While the number of university-educated Western voters continues to grow, in many democracies non-degree holders still form a large share of the electorate. According to the OECD, in 2016, the average share of voters between the ages of 25 and 64 without tertiary education in the European Union was 66% of the population. In Italy, it exceeded 80%. In many major democracies, such as France, although the representation of women and ethnic minorities in the corridors of power has increased, the same cannot be said for the working-class and non-degree holders.[70]

In the United States, especially since the 1970s, working-class voters, who had previously formed the backbone of support for the New Deal introduced by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, have been turning away from the left-leaning Democratic Party in favor of the right-leaning Republican Party.[69] Starting in the 1980s, the boomers became more conservative, many of them regretting the cultural changes they brought in their youth. The baby boomers became the largest voting demographic in the early 1980s and helped to elect Ronald Reagan as president.[72] As the Democratic Party attempted to make itself friendlier towards the university-educated and women during the 1990s, more blue-collar workers and non-degree holders left.[69]

In both Europe and the United States, older voters are the primary support base for the rise of nationalist and populist movements, though there are pockets of support among young people as well.[69] During the 2010s, a consistent trend in many Western countries is that older people are more likely to vote than their younger countrymen, and they tend to vote for more right-leaning (or conservative) candidates.[73][74][75]

Key generation milestones

In the 1985 study of U.S. generational cohorts by Schuman and Scott, a broad sample of adults was asked, "What world events over the past 50 years were especially important to them?"[76] For the baby boomers the results were:

- Baby Boomer cohort number one (born 1946–55), the cohort who epitomized the cultural change of the 1960s

- Memorable events: the Cold War (and associated Red Scare), the Cuban Missile Crisis, assassinations of JFK, Robert Kennedy, and Martin Luther King, Jr., political unrest, walk on the moon, risk of the draft into the Vietnam War or actual military service during the Vietnam War, anti-war protests, social experimentation, sexual freedom, drug experimentation, the Civil Rights Movement, environmental movement, women's movement, protests and riots, and Woodstock.

- Key characteristics: experimental, individualism, free spirited, social cause oriented.

- Baby Boomer cohort number two (born 1956–64), the cohort who came of age in the "malaise" years of the 1970s

- Memorable events: the Cold War, the Cuban Missile Crisis and the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, and Martin Luther King, Jr., for those born in the first couple of years of this generation, the Vietnam War, walk on the moon, Watergate and Nixon's resignation, lowered drinking age to 18 in many states 1970–1976 (followed by raising back to 21 in the mid-1980s as a result of congressional lobbying by Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD)), the oil embargo, raging inflation, gasoline shortages, economic recession and lack of viable career opportunities upon graduation from high school or college, Jimmy Carter's reimposition of registration for the draft, the Iran hostage crisis, Ronald Reagan, Live Aid

Legacy

An indication of the importance put on the impact of the boomer was the selection by TIME magazine of the Baby Boom Generation as its 1966 "Man of the Year." As Claire Raines points out in Beyond Generation X, "never before in history had youth been so idealized as they were at this moment." When Generation X came along it had much to live up to according to Raines.[77]

See also

References

- Sheehan, Paul (September 26, 2011). "Greed of boomers led us to a total bust". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on May 21, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- Owram, Doug (1997), Born at the Right Time, Toronto: Univ Of Toronto Press, p. x, ISBN 0-8020-8086-3

- Jones, Landon (1980), Great Expectations: America and the Baby Boom Generation, New York: Coward, McCann and Geoghegan

- Owram, Doug (1997), Born at the Right Time, Toronto: Univ Of Toronto Press, p. xi, ISBN 0-8020-8086-3

- Woodruff, Judy; French, Howard (August 1, 2016). "The unprecedented aging crisis that's about to hit China". PBS Newshour. Retrieved August 13, 2020.

- Reader's Digest August 1951 pg. 5

- "How Baby Boomers, Generation X, and Millennials Got Their Names". May 1, 2018.

- Nason, Leslie J. (January 28, 1963). "Baby Boomers, Grown Up, Storm Ivy-Covered Walls". Daily Press. Newport, Virginia. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- "baby boomer". Oxford English Dictionary. 1974.

- "Vital Statistics of the United States: 1980–2003". Table 1-1. Live births, birth rates, and fertility rates, by race: United States, 1909–2003. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- "Definition of Baby Boomer". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "Defining generations: Where Millennials end and post-Millennials begin". Pew Research Center. March 2018. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- Colby, Sandra L.; Ortman, Jennifer M. (May 2014). "The Baby Boom Cohort in the United States: 2012 to 2060" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- Bump, Philip (March 25, 2014). "Here Is When Each Generation Begins and Ends, According to Facts". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- Sincavage, Jessica. "The labor force and unemployment:three generations of change" (PDF). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- Angeles, Domingo. "Younger baby boomers and number of jobs held". U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "Distribution of Household Wealth in the U.S. since 1989". Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. December 23, 2019. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- "This Week on Gallup.com: Looking Once More at Baby Boomers". Gallup. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- Green, Brent (2006). Marketing to Leading-Edge Baby Boomers: Perceptions, Principles, Practices, Predictions. New York: Paramount Market Publishing. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0976697351.

- "POPULATION BY AGE AND SEX, AUSTRALIA, STATES AND TERRITORIES". Australian Bureau of Statistics. December 20, 2018. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- Pennay, Darren; Bongiorno, Frank (January 25, 2019). "Barbeques and black armbands: Australians' attitudes to Australia Day" (PDF). Social Research Center. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- Salt, Bernard (2004), The Big Shift, South Yarra, Vic.: Hardie Grant Books, ISBN 978-1-74066-188-1

- Salt, Bernard (November 2003). "The Big Shift" (PDF). The Australian Journal of Emergency Management. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2009. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- Jones, Landon Y. (November 6, 2015). "How 'baby boomers' took over the world" (PDF). The Washington Post. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 28, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- Howe, Neil; Strauss, William (1991). Generations: The History of Americas Future, 1584 to 2069. New York: William Morrow. pp. 299–316. ISBN 0-688-11912-3.

- Canada (June 24, 2006). "By definition: Boom, bust, X and why". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on May 20, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- Owram, Doug (1997), Born at the Right Time, Toronto: University Of Toronto Press, p. xiv, ISBN 0-8020-8086-3

- Williams, Jeffrey J. (March 31, 2014). "Not My Generation". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- FNP Interactive - http://www.fnpInteractive.com (December 19, 2008). "The Frederick News-Post Online – Frederick County Maryland Daily Newspaper". Fredericknewspost.com. Archived from the original on February 6, 2009. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- Noveck, Jocelyn (2009-01-11), "In Obama, many see an end to the baby boomer era"..

- The Original Generation X, 1954–63

- Baby Boomers Are Different Than Generation Jones – We're Proud Of Being Old

- How to tell if you’re part of ‘Generation Jones’

- Kaufmann, Eric (2013). "Chapter 7: Sacralization by Stealth? The Religious Consequences of Low Fertility in Europe". In Kaufmann, Eric; Wilcox, W. Bradford (eds.). Whither the Child? Causes and Consequences of Low Fertility. Boulder, Colorado, United States: Paradigm Publishers. pp. 135–56. ISBN 978-1-61205-093-5.

- Kaufmann, Eric (Winter 2010). "Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth?". Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review. 99 (396, the future of religion): 387–94. JSTOR 27896504.

- "Two new books explain the Brexit revolt". Britain. The Economist. November 3, 2018. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- Duarte, Fernando (April 8, 2018). "Why the world now has more grandparents than grandchildren". Generation Project. BBC News. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Barry, Sinead (June 19, 2019). "Fertility rate drop will see EU population shrink 13% by year 2100; active graphic". World. Euronews. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- Desjardins, Jeff (April 18, 2019). "Median Age of the Population in Every Country". Visual Capitalist.

- Varzally, Allison (2005). "Book Review: The Rise and Fall of Anglo-America". The Journal of American History. 92 (2): 680–681.

- Garraty, John A. (1991). "Chapter XXXI: The Best of Times, The Worst of Times". The American Nation: A History of the United States. Harper Collins Publishers. pp. 857–8. ISBN 0-06-042312-9.

- Garraty, John A (1991). "Chapter XXXIII: Our Times". The American Nation: A History of the United States. Harper Collins. pp. 932–3. ISBN 0-06-042312-9.

- Fry, Richard (April 28, 2020). "Millennials overtake Baby Boomers as America's largest generation". Pew Research Center. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Economy faces bigger bust without Boomers, Reuters, Jan 31, 2008

- Chosewood, L. Casey (July 19, 2012). "Safer and Healthier at Any Age: Strategies for an Aging Workforce". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- https://time.com/4463495/election-baby-boomers/

- Sullivan, Andrew (November 6, 2007). "Goodbye to all of that". Theatlantic.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2010. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- Broder, John M. (January 21, 2007). "Shushing the Baby Boomers". The New York Times. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- Isabel Sawhill, Ph.D; John E. Morton (2007). "Economic Mobility: Is the American Dream Alive and Well?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 29, 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- Steuerle, Eugene; Signe-Mary McKernan; Caroline Ratcliffe; Sisi Zhang (2013). "Lost Generations? Wealth Building Among Young Americans" (PDF). Urban Institute. Retrieved March 22, 2013.

- "The Whys and Hows of Generations Research". Pew Center. September 3, 2015

- Gillon, Steve (2004) Boomer Nation: The Largest and Richest Generation Ever, and How It Changed America, Free Press, "Introduction", ISBN 0-7432-2947-9

- "Population: Babies Mean Business", Newsweek, August 9, 1948. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- "Baby Boom", Time, February 9, 1948. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- Planes, Alex (June 29, 2013). "How the Baby Boomers Destroyed America's Future". The Motley Fool. The Motley Fool. Archived from the original on July 10, 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- Lyons, Linda (January 4, 2005). "Teens Stay True to Parents' Political Perspectives". Gallup Poll. Retrieved November 2, 2019.

- Garraty, John A. (1991). "Chapter XXX The American Century - Postwar Society: The Baby Boomers". The American Nation – A History of the United States (7th ed.). Harper Collins Publishers. pp. 822–24. ISBN 0-06-042312-9.

- French, Howard (June 2020). "China's Twilight Years". The Atlantic. Retrieved August 13, 2020.

- Ostling, Richard N., "The Church Search", April 5, 1993 Time article retrieved 2007-01-27

- News, ABC. "50% of Boomers Leave Estates to Kids". ABC News.

- Baby boomers lag in preparing funerals, estates, etc. The Business Journal of Milwaukee – December 18, 1998 by Robert Mullins. Retrieved 2007-06-18.

- Article in The New York Times, March 30, 1998 Archived July 9, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- "Retirement? For More Baby Boomers, The Answer Is No". ThirdAge Staff. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- "Redefining Retirement: A Much Longer Lifespan means more to Consider". Living Better at 50. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- "Financial Security and Mobility". www.economicmobility.org.

- Ellis, David (May 25, 2007). "Making less than dad did". CNN. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- "How baby boomers will affect the health care industry in the U.S. | Carrington.edu". carrington.edu. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- McNulty, Matthew (November 13, 2019). "Baby boomers are less likely than millennials to order groceries online". FOXBusiness. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- Eatwell, Roger; Goodwin, Matthew (2018). "Chapter 6: De-alignment". National Populism – The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy. Great Britain: Pelican Book. ISBN 978-0-241-31200-1.

- Eatwell, Roger; Goodwin, Matthew (2018). "Chapter 3: Distrust". National Populism – The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy. Great Britain: Pelican Book. ISBN 978-0-241-31200-1.

- Eatwell, Roger; Goodwin, Matthew (2018). "Chapter 1: Myths". National Populism – The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy. Great Britain: Pelican Book. ISBN 978-0-241-31200-1.

- Bowman, Karlyn (September 12, 2011). "As the boomers turn". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- "The myth of the 2017 'youthquake' election". UK. BBC News. January 29, 2018. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- Sopel, Jon (December 15, 2019). "Will UK provide light bulb moment for US Democrats?". US & Canada. BBC News. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- Kight, Stef W. (December 14, 2019). "Young people are outnumbered and outvoted by older generations". Axios. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- Schuman, H. and Scott, J. (1989), Generations and collective memories, American Sociological Review, vol. 54 (3), 1989, pp. 359–81.

- Raines, Claire (1997). Beyond Generation X. Crisp Publications. ISBN 978-1560524496.

Further reading

- Betts, David (2013). Breaking The Gaze. Kindle. ISBN 1494300079.

- Cheung, Edward (2007). Baby Boomers, Generation X and Social Cycles, Volume 1: North American Long-waves. Longwave Press. ISBN 9781896330068.

- Green, Brent (2010). Generation Reinvention: How Boomers Today Are Changing Business, Marketing, Aging and the Future. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4502-5533-2.

- Foot, David K. (1996). Boom Bust & Echo--How to Profit From the Coming Demographic Shift. Toronto, Canada: Macfarlane, Walter & Ross. ISBN 0-921912-97-8.

External links

- Booming: Living Through the Middle Ages - a New York Times series about baby boomers

- Baby Boomers at Curlie

- Baby boomers of New Zealand and Australia

- Boomer Revolution, CBC documentary

- Population pyramids of the EU-27 without France and of France in 2020. Population pyramids of the developed world without the U.S. and of the U.S. in 2030. Zeihan on Geopolitics.