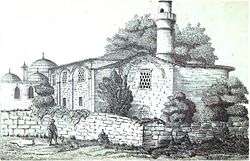

Ese Kapi Mosque

Ese Kapi Mosque (Turkish: Ese Kapı Mescidi or Hadim Ibrahim Pasha Mescidi, where mescit is the Turkish word for a small mosque), also "Isa Kapi Mosque", meaning in English "Mosque of the Gate of Jesus", was an Ottoman mosque in Istanbul, Turkey. The building was originally a Byzantine Eastern Orthodox church of unknown dedication.[1]

Location

The remains of the church lie in the Fatih district of Istanbul, in the neighborhood (Turkish: Mahalle) of Davutpaşa,[2] about 500 meters east-northeast of the Sancaktar Hayrettin Mosque, another Byzantine building. The ruins of the edifice are enclosed in the complex of Cerrahpaşa University Hospital.

History

Byzantine Age

The origin of this Byzantine building, which lay on the southern slope of the seventh hill of Constantinople in the neighborhood named ta Dalmatou and overlooked the Sea of Marmara, is not certain. It was erected along the south branch of the Mese road, just inside the now disappeared Wall of Constantine (dating to the foundation of Constantinople by Constantine the Great) in correspondence of an ancient gate, possibly the Gate of Exakiónios (Greek: Πύλη τοῦ Ἐξακιονίου) or the Gate of Saturninus (Greek: Πύλη τοῦ Σατουρνίνου, the city's original Golden Gate). The comparison of the brickwork with those of the Pammakaristos and Chora churches suggests that the building was erected between the end of the thirteenth and the beginning of the fourteenth century, in the Palaiologan era.[1] The proposed identification with the Monastery of Iasités (Greek: Μονῆ τοῦ Ἰασίτου), which lay in the neighborhood, remains uncertain.[3]

Ottoman Age

After the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453, in 1509 the Gate which gave the Turkish name to the building, ("Isa Kapi", gate of Jesus) was destroyed by an earthquake.[1] Between 1551 and 1560 Vizier Hadim Ibrahim Pasha (d. 1562/63) – who endowed also in the nearby neighborhood of the Gate of Silivri (Turkish: Silivrikapi) a Friday mosque bearing his name – converted the building into a small mosque (Turkish: Mescit). At the same time he let Court Architect Mimar Sinan (who also designed the Friday Mosque) enlarge the existing complex. Sinan built a Medrese (Koranic school) and a Dershane (elementary school) connecting them to the ancient church.[4][5] The location of these religious establishments in sparsely settled neighborhoods along the city's Theodosian Walls, where the population was predominantly Christian, shows the Vizier's desire of pursuing a policy of islamization of the city.[4] During the seventeenth century the complex was damaged several times by earthquakes, and restored in 1648.[6] In 1741 Ahmet Agha – another chief eunuch (Ibrahim Pasha in the charter of his waqf had designated the current chief white eunuch of the Imperial Harem as administrator (Turkish: Mütevelli) [7] of the endowment)[4] – sponsored the construction of a small fountain (Turkish: Sebil).[5][6] The 1894 Istanbul earthquake ruined the building (only two walls withstood the quake), which was then abandoned.[6] The ruins are now enclosed in the garden of Cerrahpaşa Hospital, seat of the Faculty of Medicine of Istanbul University.

Description

The edifice had a rectangular plan with sides of 17.0 m and 6.80 m,[6] and had one nave which ended towards East with a Bema and a three apses.[8] The central apse was demolished during the Ottoman period and replaced with a wall. The edifice's brickwork consisted of courses of rows of white stones alternating with rows of red bricks,[6] obtaining a chromatic effect typical of the late Byzantine period. The external side of a surviving wall is divided with Lesenes surmounted by arches.[6] Most likely the church was originally surmounted by a dome, but in the nineteenth century this had already been replaced with a wooden roof. The church interior was adorned with frescoes of the Palaiologan Age. Two of them – painted in the south apse – one depicting respectively the Archangel Michael (on the Conch) and the St. Hypatius (on the side wall), were still visible in 1930, but now have disappeared.[1][3] On the two walls still standing are still visible decorations in stucco.[5]

Two sides of the court are occupied by a medrese (English: Coranic school) with eleven Cells to lodge the students (Turkish: hücre) and a dershane (English: primary school).[1][5] The tight space constraints (the complex was encroached by several roads) forced Sinan to adopt a plan which strongly diverts from the standard solution for a complex of this kind.[6] The brickwork of the medrese adopts a bichromatic pattern similar to that used in the church. The dershane is decorated with a frieze made of stucco arabesques in relief.[5] The entrance of the court is adorned with a small Sebil.[5]

References

- Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 118.

- "Archaeological Destructıon in Turkey, preliminary report" (PDF), Marmara Region – Byzantine, TAY Project, p. 29, retrieved April 13, 2012

- Janin (1953) p.264

- Necipoĝlu (2005), p.392

- Eyice (1955), p.90

- Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 119.

- Boyar & Fleet (2010), p. 146

- Mamboury (1953) p.302

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ese Kapi Mosque. |

- Mamboury, Ernest (1953). The Tourists' Istanbul. Istanbul: Çituri Biraderler Basımevi.

- Janin, Raymond (1953). La Géographie Ecclésiastique de l'Empire Byzantin. 1. Part: Le Siège de Constantinople et le Patriarcat Oecuménique. 3rd Vol. : Les Églises et les Monastères (in French). Paris: Institut Français d'Etudes Byzantines.

- Eyice, Semavi (1955). Istanbul. Petite Guide a travers les Monuments Byzantins et Turcs (in French). Istanbul: Istanbul Matbaası.

- Müller-Wiener, Wolfgang (1977). Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls: Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul bis zum Beginn d. 17 Jh (in German). Tübingen: Wasmuth. ISBN 9783803010223.

- Necipoĝlu, Gulru (2005). The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-244-7.

- Boyran, Ebru; Fleet, Kate (2010). A social History of Ottoman Istanbul. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19955-1.