Assyrians/Syriacs in Sweden

Assyrians/Syriacs in Sweden (Swedish: Assyrier/Syrianer i Sverige) are citizens and residents of Sweden who are of Assyrian/Syriac descent. There are approximately 150,000 Assyro-Syriacs in Sweden.[2]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 150,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Södertälje, Stockholm, Gothenburg, Örebro, Västerås, Norrköping, Linköping, Skövde, Jönköping, Tibro | |

| Languages | |

| Neo-Aramaic · Swedish | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity (majority: Syriac Christianity; minority: Protestantism) |

Assyrians/Syriacs first came to Sweden from Lebanon for work in the late 1960s when Europe needed laborers for its industries. However, with increased ethnic and religious persecution in their homeland, which is located in present-day southeastern Turkey, northern Iraq, northwestern Iran and northeastern Syria,[3] Assyrian/Syriac immigration to Sweden increased. Those who had lived in Sweden for a longer period of time were granted residency for humanitarian reasons, given the conflicts in their place of origin.[4]

History

Early immigration (1960s-1970s)

After the Assyrian genocide of 1915, it became clear that violence against the native Christian populations were widespread. In the 1960s, it became increasingly unsafe for Assyrians/Syriacs in Midyat, the regional centre of Tur Abdin. Muslims incited violent anti-Christian protests as a response to events unfolding in Cyprus. This led to many Assyro-Syriacs not seeing a future for themselves in their ancestral homeland.[5]

On Thursday 9 March 1967, 108 stateless Assyrians/Syriacs left Beirut airport in Lebanon en-route to Sweden where they landed at Bulltofta airport outside of Malmö. After being bathed upon arrival, the Assyrians/Syriacs were transported by bus to a refugee housing complex in Alvesta in the province of Småland. Over a month later on Thursday, 13 April, a second group of 98 Assyrian/Syriac refugees arrived from Beirut. The reason behind the initial immigration of Assyrians/Syriacs to Sweden was the introduction of a quota of 200 Christians from Lebanon that were to be accepted by the Swedish Public Employment Service after coordination with the World Council of Churches and the United Nation High Commissioner for Refugees. A group of Swedish public officials visited Beirut where a selection of mostly young families from Turkey that were members of the Syriac Orthodox Church, as well as Protestants and members of the Assyrian Church of the East were accepted to immigrate to Sweden.[6] [7]

Assyrians/Syriacs of Södertälje were involved in a riot on 19 June 1977, when raggare (greasers), mainly coming from nearby Stockholm attacked them at Restaurant Bristol in Södertälje, at the time the attack being believed that it was racially motivated. This was part of the raggare-scare that existed during those times. Mass media added fuel to the riots with headlines about "race riots" and "Södertälje - a city gripped by fear". It was said that the greasers' aversion towards the Assyrians/Syriacs was because the latter taking up too much space, talking loudly, walking around well-dressed and wearing gold chains. There were also rumours about the Assyrians taking over the city.[8]

Demographics

Södertälje is seen as the unofficial Assyrian/Syriac capital of Europe due to the city's high percentage of Assyrians/Syriacs. According to Assyrian/Syriac organization estimates, there are approximately 150,000 Assyrians/Syriacs in Sweden.[10] The Syriac Orthodox christians number an estimated 30,000–40,000 people (2016), while higher estimations is 70–80,000, out of which an estimated 18,000 live in Södertälje.[11]

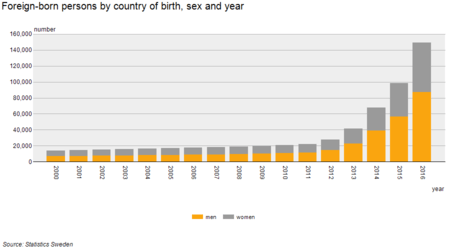

According to Statistics Sweden, as of 2016, there 22,663 are citizens of Iraq (12,705 men, 9,958 women) and 116,384 citizens of Syria (70,060 men, 46,324 women) residing in Sweden.[12]

Culture

Identity

There is an ideological division of this group in Sweden between[13]

- Arameanists, largely adherents of the Syriac Orthodox Church (West Syrian Rite) hailing largely from Lebanon, northeast Syria and south central Turkey, who insist on the name Syrianer and an "Aramean" heritage for the group.

- Assyrianists mostly adherents of the Assyrian Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church and various Protestant churches, hailing largely from Iraq, Iran and northeast Syria, who de-emphasize religious adherence in favour of ethnicity pre-Christian antiquity, who insist on the name Assyrier and an Assyrian-Mesopotamian heritage for the group.

To account for this division, official Swedish sources refer to the group as "Assyrier/Syrianer",[14] with a slash (similar to the US census, which opted for "Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriac").

Organisations

When Assyrians/Syriacs immigrated to Sweden, they formed cultural organisations that would represent their people, as well as act as a centre for Assyrians/Syriacs in Sweden to meet. The Assyrian Federation of Sweden (AFS) was founded in 1977 as a nationwide umbrella organisation for the various local associations in Sweden. The formation took place on 15–17 April 1977, with twenty-one representatives from eleven associations present, unanimously deciding to unite into a national organisation. At the national assembly in 1983, 44 representatives from 21 associations were present. Initially, the Federation had 3,000 members which soon doubled by 1980. At first, the Federation's office was located in Norsborg, but soon moved to Södertälje in 1983.

Aside from the Assyrian Federation of Sweden, the Assyrian Youth Federation and Assyrian Women's Federation existed nationwide. The Youth Federation was formed in 1985 as the Assyrian Youth Committee within the AFS. In 1991, it was transformed into the Assyrian Youth Federation, and became more independent from the AFS.

The Syriac (Aramean) Federation of Sweden was founded in 1978. The federation is safeguarding the interest in the linguistic, cultural, ethnic, and social issues of the Aramean people. The federation has about 19.000 members and 34 sub-associations.[15]. The federation is collaborating with numerous organizations in Sweden that provides assistants needed for the federation and its operations.[16]

Media

Publications

In 1978, Hujådå, the first Assyrian magazine was published by the Assyrian Federation of Sweden. The etymology of the name has the meaning "unity" or "union" in the Aramaic language, with the intention to unite all Assyrians, regardless of church, and to pay homage to Naum Faiq's publication with the same name in the United States in the early 1920s. The first issue of Hujådå came out in spring of 1978 and was published by Gabriel Afram, the then chairman of AFS, and the editor in-chief, Johanon Kashisho. In the beginning, the magazine contained material in four languages: Aramaic, Arabic, Turkish and Swedish. Eventually, material was published in English. Currently, Hujådå only exists as a web publication. [17]

The second Aramean magazine was published by the Aramean Federation of Sweden called Bahro Suryoyo. It is published in five languages: Swedish, Aramaic, Arabic, English, and Turkish. It is available as an online magazine since 2009.[18][19] It is available as an online magazine since 2009 at bahro.nu.[20]

Television

In the mid-2000s, Assyrian/Syriac TV channels were formed in Södertälje. Suroyo TV is operated by the Dawronoye political movement, while the Syriacs identifying as "Aramean" created Suryoyo Sat. The AFS, Women's Federation and Youth Federation founded the Assyrian Media Institute (AMI) on 24 September 2011, in Norrköping. AMI owns and operates Assyria TV, a web TV channel, which broadcasts shows worldwide, commonly interviewing famous Assyrians, as well as famous Swedish politicians and scholars. Assyria TV has also played a role in exposing Kurdish acts of cruelty against Assyrians in Iraq and Syria. [21]

Religion

In the 1990s, the Syriac Orthodox Church in Sweden fell into disunion with the church's board shutting the bishop out and demanding that the Patriarch in Damascus appoint a new bishop. In 1996, a new bishop was appointed, resulting in the Syriac Orthodox Church in Sweden being divided into two separate dioceses with their own bishops, both based in Södertälje. The diocese which does not reject the Assyrian name is led from St. Jacob of Nisibi's Cathedral in Hosvjö. The other diocese is led from St. Afrem's Church in Geneta.[22]

Sport

Assyrians/Syriacs have a wide spanning history in relation to sports in Sweden, most notably in the football arena. In Qamishli and Tur Abdin, Assyrians/Syriacs had their own football clubs that played at a local or national level. This led to the formation of ethnic-based Assyrian/Syriac clubs in Sweden who have enjoyed a high level of success relative to other ethnic groups. Currently, there are over 20 Assyrian/Syriac ethnic-based clubs present across Sweden.

On 14 February 1974, Assyriska FF was established in Södertälje. In the year 2000, Assyriska FF joined the Superettan when it was founded and boast the most seasons in the competition at 15. In 2003, Assyriska FF qualified for the Swedish Cup Final, before falling short to Elfsborg 0-2 in the final. In 2005, Assyriska FF managed to reach the highest level of football in Sweden, the Allsvenskan, becoming the first ethnic club to reach the competition. Their first game of the season was played on 12 April at Råsunda Stadium against Hammarby where Assyrian-American singer Linda George performed in front of an audience of 15,000.

In 1977 the club Syrianska FC was also established in Södertalje. In 2010, after two years in Superettan, Syrianska was promoted to Allsvenskan (the highest tier in Swedish football) for the first time in club history. 3 years later in 1980 another club was found Arameisk-Syrianska IF playing in the third highest Swedish league, Division 1.

Notable people

- Denho Acar, Assyrian criminal, born in Midyat, Turkey.[23]

- Ibrahim Baylan, Syriac politician, born and raised in Deir Salih, Tur Abdin, Turkey.[24]

- Abgar Barsom, Syriac-Aramean former footballer.[25]

- Kennedy Bakircioglu, Assyrian footballer,[26] family arrived in 1972 from Midyat.

- Jimmy Durmaz, Syriac footballer,[27] father from Midyat in Turkey.[28]

- David Durmaz, Syriac footballer, family from southeastern Turkey.[29]

- Yilmaz Kerimo, Assyrian-Syriac politician, born in Turkey.[30]

- Alexander Michel Melki, Syriac footballer.

- Felix Michel Melki, Syriac footballer.

- Bishara Morad, known by the mononym Bishara, Syriac singer from Syria born 2003, took part in Melodifestivalen 2019.[31]

- Suleyman Sleyman, Syriac footballer.[32]

- Daniel Teymur, Syriac MMA fighter.[33]

- Sharbel Touma, Aramean footballer, born in Lebanon.[34]

References

- SVT: Statministerns folkmordsbesked kan avgöra kommunvalet: ”Underskatta inte frågan” (in Swedish)

- SVT: Statministerns folkmordsbesked kan avgöra kommunvalet: ”Underskatta inte frågan” (in Swedish)

- Sargon Donabed (1 February 2015). Reforging a Forgotten History: Iraq and the Assyrians in the Twentieth Century. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-0-7486-8605-6.

- Swedish Minister for Development Co-operation, Migration and Asylum Policy, Migration 2002, June 2002 Archived 26 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Lundgren, Svante. The Assyrians: Fifty Years in Swedenq. Nineveh Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-91-984101-7-4.

- Tore Wizelius; Lars-Sune Hansson; Sweden. Referensgruppen för folkrörelsefrågor; Sweden. Statens invandrarverk (1984). Föreningar bland invandrare och minoriteter i Sverige. Statens invandrarverk. p. 53.

- Lundgren, Svante. The Assyrians: Fifty Years in Sweden. Nineveh Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-91-984101-7-4.

- Lundgren, Svante. The Assyrians: Fifty Years in Sweden. Nineveh Press. pp. 22–24.

- "Foreign-born persons by country of birth, age, sex and year". Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- Prakash Shah; Marie-Claire Foblets (15 April 2016). Family, Religion and Law: Cultural Encounters in Europe. Routledge. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-317-13648-4.

Syriac Orthodox

- "Foreign citizens by country of citizenship, sex and year". Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- Dan Lundberg, Christians from the Middle East

- Riksdagens protokoll. Kungl. Boktr. 2001.

assyrier/syrianer

- "Syrianska riksförbundet". www.sios.org (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 18 November 2008. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "List of Co-Operative Organisations".

- Lundgren, Svante. The Assyrians: Fifty Years in Sweden. Nineveh Press. pp. 91–92.

- Bahro Suryoyo

- "Bahro suryoyo : månatlig kultur-, idrotts-, nyhets- och informationstidning". Archived from the original on 26 August 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- "Om Bahro.nu". Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- Lundgren, Svante. The Assyrians: Fifty Years in Sweden. Nineveh Press. pp. 97–98.

- Lundgren, Svante. The Assyrians: Fifty Years in Sweden. Nineveh Press. p. 64.

- Bahar Baser; Paul T. Levin (30 June 2017). Migration from Turkey to Sweden: Integration, Belonging and Transnational Community. I.B.Tauris. pp. 230–. ISBN 978-1-78672-245-4.

- ""Baylan började hos mig när han var sju år"" (in Swedish). SVD.

- "Syrianske stjärnan Abgar Barsom tackar Syrianska folket".; Grimlund, Lars (2004). "Artisten Barsom vill vara perfekt". DN.

- "Zweedse Assyriër in Twente" [Swedish-Assyrian in Twente]. De Pers (in Dutch). 9 March 2007. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- Max Wiman (2011). "Ur ilskan växte årets stora succé" (in Swedish).

- "Jimmy Durmaz ska underlätta flytt - kan skaffa turkiskt pass" (in Swedish). Fotbolltransfers.

- "David Durmaz om mötet med sin nya klubb". Svenska fans.

- "yilmazkerimo". socialdemokraterna.

- Johan M Söderlund and Torbjörn Ek (24 February 2019). "Så drillades Bishara Morad av Laila Bagge". Aftonbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- "Sleyman". SVD.

- "UFC-fightern: "Bältet är mitt mål"" (in Swedish). SVT.

- "Voormalig FC Twente-speler Touma keert terug naar jeugdliefde". voetbalzone.; "Touma kan ersätta Porokara". na.se.

Further reading

- Svenska kommunförbundet (1982). Assyrier/syrianer: tipskatalog : några fakta om gruppen och några exempel från kommunal verksamhet. Kommunförb.

- Knutsson, Bengt (1982). Assur eller Aram: språklig, religiös och nationell identifikation hos Sveriges assyrier och syrianer. Statens invandrarverk (SIV).

- Klich, I., and Ingvar Svanberg. "Assyrier/syrianer" i." Det mångkulturella Sverige (1988).

- Yalcin, Zeki. "Svenskar och assyrier/syrianer kring sekelskiftet 1900." Multiethnica. Meddelande från Centrum för multietnisk forskning, Uppsala universitet 29 (2003): 24-28.

- Björklund, Ulf. North to another country: the formation of a Suryoyo community in Sweden. Vol. 9. Dept. of Social Anthropology, University of Stockholm, 1981.

- Atman, Sabri. Assyrier-Syrianer. Mesopotamien, 1996.

- Barsom, Gabriella. "En studie om assyriska/syrianska ungdomars språkbruk och språkidentiteter." (2006).

- Berntson, Martin. "Assyrier eller syrianer? Om fotboll, identitet och kyrkohistoria." rapport nr.: Humanistdag-boken 16 (2003).