Asilah

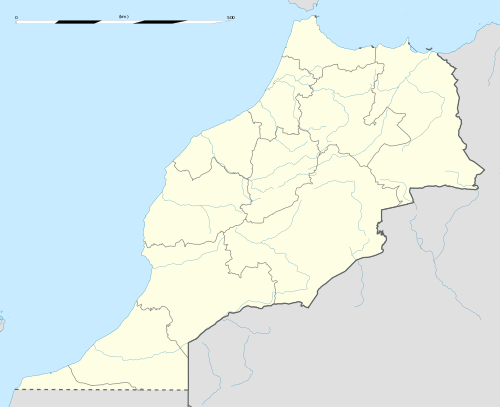

Asilah (Berber: Aẓila; Arabic: أزيلا or أصيلة; Portuguese: Arzila), also written Arzeila,[2] is a fortified town on the northwest tip of the Atlantic coast of Morocco, about 31 km (19 mi) south of Tangier. Its ramparts and gateworks remain fully intact.

Asilah Aẓila / أصيلة / أزيلا | |

|---|---|

.jpg)     Clockwise from top: seaside walls and cemetery of the medina; street inside the medina; Grand Mosque; seaside view of the city; coastline near the city; a roundabout in the modern town. | |

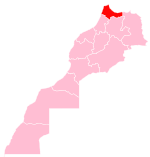

Asilah Location in Morocco | |

| Coordinates: 35°28′N 6°2′W | |

| Country | |

| Region | Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima |

| Population (2014)[1] | |

| • Total | 31,147 |

History

The town's history dates back to 1500 B.C., when Phoenicians occupied a site called Silis, Zili, Zilis, or Zilil (Punic: 𐤀𐤔𐤋𐤉𐤕, ʾŠLYT,[3] or Punic: 𐤔𐤋𐤉, ŠLY)[4] which is being excavated at Dchar Jdid, some 12 km (7.5 mi) NE of present Asilah; that place was once considered to be the Roman stronghold Ad Mercuri, but is now accepted to be Zilil. The town of Asilah itself was partly constructed by the Idrisid dynasty,[5] and Cordoban caliph Al-Hakam II rebuilt the town in 966.[6] The Portuguese conquered the city in 1471 and built its fortifications, but it was abandoned it because of an economic debt crisis in 1549.[7] In 1578, Sebastian of Portugal used Asilah as a base for his troops during a planned crusade that resulted in Sebastian's death, which in turn caused the Portuguese succession crisis of 1580. In 1589 the Moroccans briefly regained control of Asilah, but then lost it to the Spanish.[8]

In 1692, the town was again taken by the Moroccans under the leadership of Moulay Ismail. Asilah served then as a base for pirates in the 19th and 20th centuries, and in 1829, the Austrians punitively bombarded the city due to Moroccan piracy.[9]

From 1912 to 1956, it was part of Spanish Morocco. A major plan to restore the town was undertaken in 1978 by its mayor, Mohamed Benaissa. Benaissa and painter Mohamed Melehi were instrumental in organizing an art festival, the International Cultural Moussem of Asilah, that starting in 1978 began generating tourism income. It is credited with having promoted urban renewal in Asilah, and is one of the most important art festivals in the country.[10] It played a role in raising the average monthly income from $50 in 1978 to $140 in 2014. The festival features local artwork and music and continues to attract large numbers of tourists.[11]

Asilah is now a popular seaside resort, with modern holiday apartment complexes on the coast road leading to the town from Tangier.[12] The old neighborhoods are restored and painted white, and the wealthy from Casablanca have their weekend getaways here.[6]

Culture

While tourism dominates, Asilah is said to offer a good introduction to Morocco.[6] It hosts annual music and arts festivals, including a mural-painting festival. Thursday is market day.[13] The International Cultural Festival, held in August, features jazz and Moroccan music as well as art exhibitions.[6] The festival is also the occasion for mural painting in which the medina's houses are painted with new murals every year.[12][14][15]

Many of the houses of Asilah feature mashrabiya (oriel windows). The main cultural center is the Centre Hassan II des Rencontres Internationales (housed in a former Spanish barracks[15]), which hosts festivals in the summer.[13]

Due to its proximity to Spain, the cuisine in Asilah is described as Ibero-Moroccan with notable delicacies including paella, anchovies, and other seafood with both Moroccan and Valencian flavor influences.[16]

Notable landmarks

The medina

The old walled town (medina) of Asilah is well-preserved and dates mostly from the Portuguese occupation (15th-16th century) and afterwards.[17] The medina has been heavily restored and its buildings are typically painted white, with occasionally blue or green, in addition to which can be found many of the murals created during the International Cultural Festival.[14] Though the Portuguese rebuilt its outline of walls, it has the typical maze-like layout and alleys of an old Moroccan city.[17]

View of the medina from the sea pier.

View of the medina from the sea pier. Street in the medina.

Street in the medina. Street and marabout's tomb in the medina.

Street and marabout's tomb in the medina. Promenade/street along the sea walls.

Promenade/street along the sea walls. Street and mural in the medina.

Street and mural in the medina. Mural in Asilah.

Mural in Asilah. Wall art in Asilah.

Wall art in Asilah..jpg) Mural featuring Arabic calligraphy.

Mural featuring Arabic calligraphy.

Walls and towers

The walls of Asilah were first built by the Almohads and then restored and reinforced by the Marinids and the Wattasids.[17] However, after the Portuguese took the city in 1471 they rebuilt the walls, making them more resistant to artillery, and modified the outline of the city, shrinking its perimeter for easier control.[17] The current walls thus date almost entirely from the Portuguese occupation, with the possible exception of some parts of the seaside walls.[17] There are two main gates in the walls, Bab Homar, in the mid-southern part of the walls, and Bab al-Qasaba, at the eastern end of the walls where the kasbah was once located.[14] A rectangular tower in distinct Portuguese style, known as Borj al-Hamra ("Red Tower") or the Al-Qamra Tower, stands near the kasbah and overlooks an open square.[15][18][17]

Seaside walls.

Seaside walls. Sea bastion at western end of the medina.

Sea bastion at western end of the medina. Bab Homar gate.

Bab Homar gate. Portuguese coat of arms still visible above Bab Homar gateway.

Portuguese coat of arms still visible above Bab Homar gateway. Bab al-Qasaba (Gate of the Kasbah).

Bab al-Qasaba (Gate of the Kasbah).- Borj al-Hamra or Al-Qamra Tower, overlooking city square.

Borj al-Hamra or Al-Qamra Tower.

Borj al-Hamra or Al-Qamra Tower.

Grand Mosque of Asilah

The Grand Mosque of Asilah is located inside the former kasbah (citadel), at the eastern end of the medina. It was built under Moulay Ismail soon after the city was retaken for Morocco at the end of the 17th century. Moulay Ismail charged the new governor of Tangier, Ali ibn Abdallah Errifi, with building the mosque; however, it's possible that it was his son, Ahmed Errifi, who actually carried out the construction.[17] It has an octagonal minaret, a feature common to some parts of northern Morocco but not in the rest of the country. With its whitewashed walls and minaret, its decoration is quite plain compared to other mosques built by the Errifis at the same time (such as the Kasbah Mosque in Tangier).[17] Like other Moroccan mosques, it is open to Muslims only.

Grand Mosque and minaret.

Grand Mosque and minaret..jpg) Entrance of the Grand Mosque.

Entrance of the Grand Mosque.

Raisuli Palace (Palais Raissouli)

This restored palace is in the mid-northern part of the medina, alongside the sea walls. It was built in 1909 by Moulay Ahmed er-Raisuni (also known as Raisuli), a local rogue and pirate who rose to power and declared himself pasha of the region.[17] He rose to notoriety and wealth partly through kidnappings and ransoms, including of several Westerners who wrote about him afterwards.[15][14] The palace has been restored and reveals some of the luxury in which Raisuli lived.[14] It includes a lavish reception room with zellij tilework, carved stucco, and painted wood like in other Moroccan palaces.[17] The reception room also gives access to a large loggia and terrace overlooking the sea.[17] Raisuli infamously claimed that he executed convicted murderers by forcing them to jump from this terrace onto the sea rocks below.[15][14]

Sidi Mansour cemetery (seaside cemetery)

At the far western end of the medina is a Portuguese bastion extending out to sea, which is a popular spot for locals and tourists at sunset.[14] In the angle between the bastion and the sea walls is a platform upon which is a small enclosed cemetery. It includes two small structures, the domed Marabout (mausoleum) of Sidi Ahmed ibn Moussa (also known as Sidi Ahmed el-Mansour and Sidi Mansour) and, across from it, the mausoleum of his sister, Lalla Mennana.[17][19][14] Between these structures, the ground is covered with other graves which are covered in colourful ceramic tiles.[17]

View of the cemetery's platform on the shore.

View of the cemetery's platform on the shore. View of the graves.

View of the graves.

Church of San Bartolome

Located in the new city outside the medina, this Roman Catholic Church was built by Spanish Franciscans in 1925.[15][14] It is still used as a convent today and is one of the only churches in Morocco allowed to ring in public for Sunday mass. Its architecture is a mix of Spanish Colonial and Moorish styles.[14][15]

Church exterior.

Church exterior. Church interior.

Church interior.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Asilah. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Asilah. |

Citations

- "Population Légale des Régions, Provinces, Préfectures, Municipalités, Arrondissements et Communes du Royaume Après les Résultats du RGPH 2014". Recensement Général de la Population et de l'Habitat 2014. Haut-Commissariat au Plan du Maroc. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- Harris, Walter. (2012). Morocco That Was. Eland Publishing. ISBN 9781906011994. OCLC 815651069.

- Head & al. (1911), p. 890.

- Maldonado López (2013), p. 78.

- Searight, Susan (1999). Maverick Guide to Morocco. Gretna: Pelican. p. 137. ISBN 9781455608645. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- Honnor, Julius (2012). Morocco Footprint Handbook. Footprint Travel Guides. ISBN 9781907263316. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- Jorge Nascimento Rodrigues; Tessaleno C. Devezas (1 December 2007). Pioneers of Globalization: Why the Portuguese Surprised the World. Centro Atlantico. p. 117. ISBN 978-989-615-056-3.

- Paula Hardy; Mara Vorhees; Heidi Edsall (2005). Morocco. Lonely Planet. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-1-74059-678-7.

- "'Abd ar-Rasham". Encyclopædia Britannica. I: A-Ak - Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2010. pp. 17. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- Pieprzak, Katarzyna (2008). "Art in the Streets: Modern Art, Museum Practice and the Urban Environment in Contemporary Morocco". Middle East Studies Association Bulletin. 42 (1/2): 48–54. doi:10.1017/S0026318400051518. JSTOR 23063542.

- Emma Katz (2014). "Art and the Economy in Amman". Journal of Georgetown University-Qatar Middle Eastern Studies Student Association. Globalization and the Middle East: Youth, Media & Resources, 7 (2014): 7. doi:10.5339/messa.2014.7.

- "The murals of Asilah". Euronews.com. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- DK Publishing (29 November 2010). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Morocco. DK Publishing. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-7566-8665-9.

- Lonely Planet: Morocco (12th ed.). Lonely Planet. 2017.

- The Rough Guide to Morocco. London: Rough Guides. 2016. ISBN 9780241236680.

- Longo, Gianluca. "The Small Moroccan City That Has Become a Haven for Art Insiders". Condé Nast Traveler. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Touri, Abdelaziz; Benaboud, Mhammad; Boujibar El-Khatib, Naïma; Lakhdar, Kamal; Mezzine, Mohamed (2010). Le Maroc andalou : à la découverte d'un art de vivre (2 ed.). Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Royaume du Maroc & Museum With No Frontiers. ISBN 978-3902782311.

- "Borj al-Kamra". Archnet. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Zaouia de Sidi Ahmed Ben Moussa". Archnet. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

Bibliography

- Head, Barclay; et al. (1911), "Mauretania", Historia Numorum (2nd ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 887–890.

- Maldonado López, Gabriel (2013), Las Ciudades Fenicio Púnicas en el Norte de África... (PDF). (in Spanish)