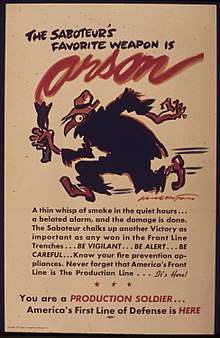

Arson

Arson[1] is a crime of willfully and maliciously setting fire to or charring property.[2] Though the act typically involves buildings, the term arson can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, watercraft, or forests.[2] The crime is typically classified as a felony, with instances involving a greater degree of risk to human life or property carrying a stricter penalty.[2] A common motive for arson is to commit insurance fraud.[2][3] In such cases, a person destroys their own property by burning it and then lies about the cause in order to collect against their insurance policy.[4]

| Criminal law | |

|---|---|

| Elements | |

| Scope of criminal liability | |

| Severity of offense | |

|

|

| Inchoate offenses | |

| Offence against the person | |

|

|

|

| Sexual offences | |

| Crimes against property | |

| Crimes against justice | |

| Crimes against the public | |

|

|

| Crimes against animals | |

| Crimes against the state | |

| Defences to liability | |

| Other common-law areas | |

| Portals | |

|

|

| Terrorism | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

|

By ideology

|

|||||||

|

Structure |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Terrorist groups |

|||||||

|

Adherents |

|||||||

|

Response to terrorism

|

|||||||

A person who commits arson is called an arsonist. Arsonists normally use an accelerant (such as gasoline or kerosene) to ignite, propel and directionalize fires, and the detection and identification of ignitable liquid residues (ILRs) is an important part of fire investigations.[5] Pyromania is an impulse control disorder characterized by the pathological setting of fires.[6] Most acts of arson are not committed by pyromaniacs.[6]

Etymology

The term derives from Law French arsoun (late 13th century), from Old French arsion, from Late Latin arsionem "a burning," from the verb ardere, "to burn."[7][8][9]

English common law

Historically, the common law crime of arson had four elements:

- The malicious

- burning

- of the dwelling

- of another[10]

- Malicious

- For purposes of common law arson, "malicious" refers to action creating a great risk of a burning. It is not required that the defendant acted intentionally or willfully for the purpose of burning a dwelling.

- Burning

- At common law charring to any part of dwelling was sufficient to satisfy this element. No significant amount of damage to the dwelling was required. Any injury or damage to the structure caused by exposure to heat or flame is sufficient.

- Of the dwelling

- 'Dwelling' refers to a place of residence. The destruction of an unoccupied building was not considered arson: "... since arson protected habitation, the burning of an unoccupied house did not constitute arson." At common law a structure did not become a residence until the first occupants had moved in, and ceased to be a dwelling if the occupants abandoned the premises with no intention of resuming their residency.[11] Dwelling includes structures and outbuildings within the curtilage.[12] Dwellings were not limited to houses. A barn could be the subject of arson occupied as a dwelling.

- Of another

- Burning one's own dwelling does not constitute common law arson, even if the purpose was to collect insurance, because "it was generally assumed in early England that one had the legal right to destroy his own property in any manner he chose".[13] Moreover, for purposes of common law arson, possession or occupancy rather than title determines whose dwelling the structure is.[12] Thus a tenant who sets fire to his rented house would not be guilty of common law arson,[12] while the landlord who set fire to a rented dwelling house would be guilty.

Degrees

Many U.S. state legal systems and the legal systems of several other countries divide arson into degrees, depending sometimes on the value of the property but more commonly on its use and whether the crime was committed in the day or night.

- First-degree arson – Burning an occupied structure such as a school or a place where people are normally present

- Second-degree arson – Burning an unoccupied building such as an empty barn or an unoccupied house or other structure in order to claim insurance on such property

- Third-degree arson – Burning an abandoned building or an abandoned area, such as a field, forest or woods.

Many statutes vary the degree of the crime according to the criminal intent of the accused. Some US states use other degrees of arson, such as "fourth" and "fifth" degree,[14] while some states do not categorize arson by any degree. For example, in the state of Tennessee, arson is categorized as "arson" and "aggravated arson".

United States

In the United States, the common law elements of arson are often varied in different jurisdictions. For example, the element of "dwelling" is no longer required in most states, and arson occurs by the burning of any real property without consent or with unlawful intent.[15] Arson is prosecuted with attention to degree of severity[16] in the alleged offense. First degree arson[17] generally occurs when people are harmed or killed in the course of the fire, while second degree arson occurs when significant destruction of property occurs.[18] While usually a felony, arson may also be prosecuted as a misdemeanor,[19] "criminal mischief", or "destruction of property."[20]

Burglary also occurs, if the arson involved a "breaking and entering".[21] A person may be sentenced to death if arson occurred as a method of homicide, as was the case in California of Raymond Lee Oyler and in Texas of Cameron Todd Willingham.

In New York, arson is charged in five degrees. Arson in the first degree is a Class A-1 felony and requires the intent to burn the building with a person inside using an explosive incendiary device. It has a maximum sentence of 25 years to life.

In California, a conviction for arson of property that is not one's own is a felony punishable by up to three years in state prison. Aggravated arson, which carries the most severe punishment for arson, is punishable by 10 years to life in state prison. Raymond Lee Oyler was ultimately convicted of murder and sentenced to death for a 2006 fire in southern California that led to the deaths of five U.S. Forest Service firefighters; he was the first U.S. citizen to receive such a conviction and penalty for wildfire arson.[22]

Some states, such as California, prosecute the lesser offense of "reckless burning" when the fire is set recklessly as opposed to wilfully and maliciously. The study of the causes is the subject of fire investigation.

England, Wales, and Hong Kong

In English law, arson was a common law offence (except for the offence of arson in royal dockyards)[23] dealing with the criminal destruction of buildings by fire. The common law offence was abolished by s.11(1) of the Criminal Damage Act 1971.[24] The 1971 Act makes no distinction as to mode of destruction except that s.1(3) requires that if the destruction is by fire, the offence is charged as arson; s.4 of the Act provides a maximum penalty of life imprisonment for conviction under s.1 whether or not the offence is charged as arson. In Hong Kong, the common law offence was abolished by s 67 of the Crimes Ordinance 1971 (Part VIII of which, as amended by Crimes (Amendment) Ordinance 1972,[25] mirrored the English Criminal Damage Act 1971).[26] Like the English counterparts, 63 of the 1972 Ordinance provides a maximum penalty of life imprisonment, and s 60(3) of the Ordinance requires that if the damage is by fire the offence should be charged as arson.

Scotland

While Scotland has no offence known as arson statutorily defined in their legal system, there are many offences that are used to charge those with acts that would normally constitute arson in other nations. Events constituting arson in English law might be dealt with as one or more of a variety of offences such as wilful fire-raising, culpable and reckless conduct, vandalism or other offences depending on the circumstances of the event. The more serious offences (in particular wilful fire-raising and culpable and reckless conduct) can incur a sentence of life imprisonment.

See also

References

- arson 1680, from Anglo-French arsoun (1275), from Old French arsion, from Late Latin arsion- (root form of arsio) "a burning," from Latin arsus past participle of ardere "to burn", from PIE base *as- "to burn, glow" (see ardent). The Old English term was bærnet, lit. "burning"; and Edward Coke has indictment of burning (1640). Arsonist is from 1864. Dictionary.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper, Historian. (accessed: January 27, 2008)

- "Arson". FindLaw. Archived from the original on January 5, 2019. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- arson. Dictionary.com. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. Accessed: January 27, 2008

- Zalma, Barry (January 8, 2014). "Fraud Proved – Lie About Cause Of Fire Sufficient to Support Guilty Verdict". LexisNexis. Archived from the original on January 5, 2019. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- Analysis and interpretation of fire scene evidence. Almirall, José R., Furton, Kenneth G. Boca Raton: CRC Press. 2004. ISBN 978-0849378850. OCLC 53360702.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Burton, Paul R.; McNiel, Dale E.; Binder, Renée L. (November 2012). "Firesetting, arson, pyromania, and the forensic mental health expert" (PDF). Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 40 (3): 355–365. PMID 22960918. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 5, 2019.

- "arson - Origin and meaning of arson by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- Various. Chambers's Twentieth Century Dictionary (part 1 of 4: A-D). Library of Alexandria. ISBN 9781465562883 – via Google Books.

- "Definition of arson - Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com.

- Black's Law Dictionary (9th ed.). 2009. Arson.

At common law, the malicious burning of someone else's dwelling house or outhouse that is either appurtenant to the dwelling house or within the curtilage.

- Boyce & Perkins, Criminal Law, 3rd ed. (1992) at 280, 281.

- Boyce & Perkins, Criminal Law, 3rd ed. (1992) at 281.

- "Arson: Legal Aspects – Common Law Arson". Law Library – American Law and Legal Information. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- Nagel, Ilene H. (1983). "The Legal/Extra-Legal Controversy: Judicial Decisions in Pretrial Release". Law & Society Review. 17 (3): 481–516. doi:10.2307/3053590. JSTOR 3053590.

- See U.S. v. Miller', 246 Fed.Appx. 369 (C.A.6 (Tenn.) 2007); U.S. v. Velasquez-Reyes, 427 F.3d 1227, 1230–1231 and n. 2 (9th Cir.2005).

- "Campus Crime: Crime Codes and Degree of Severity". California State University, Monterey Bay. Archived from the original on December 24, 2008. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- See U.S. v. Miller, 246 Fed.Appx. 369 (C.A.6 (Tenn.) 2007)

- Garofoli, Joe (September 1, 2007). "Suspect in Burning Man arson decries event's loss of spontaneity". San Francisco Chronicle. p. A8. Archived from the original on April 25, 2008. Retrieved May 11, 2008.

- "Reason for Referral". Nebraska Commission on Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice. Archived from the original on May 3, 2008. Retrieved May 11, 2008.

- "Man accused of arson pleads to misdemeanor charges". The Salina Journal. January 25, 2008. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved May 11, 2008.

- 3 Charles E. Torcia, Wharton's Criminal Law § 326 (14th ed. 1980)

- "Getting Tough on Arson". Utne Reader. January–February 2011. p. 13.

- William Blackstone (1765–1769). "Of Offenses against the Habitations of Individuals [Book the Fourth, Chapter the Sixteenth]". Commentaries on the Laws of England. Oxford: Clarendon Press (reproduced on The Avalon Project at Yale Law School). Archived from the original on May 3, 2008. Retrieved June 1, 2008..

- "Criminal Damage Act 1971". Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- Legco.gov.hk

- Hklii.hk

Further reading

- Karki, Sameer (2002). Community Involvement in and Management of Forest Fires in South East Asia (PDF). Project FireFight South East Asia. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- White, J. & Dalby, J. T., 2000. Arson. In D. Mercer, T. Mason, M. McKeown, G. McCann (Eds) Forensic Mental Health Care. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingston. ISBN 0-443-06140-8

External links

- How to combat arson

- An actual Arson Investigation Report