Arkansas Post

The Arkansas Post (French: Poste de Arkansea) was the first European settlement in the lower Mississippi River Valley and present-day Arkansas when Henri de Tonti established it in 1686 as a French trading post on the banks of the lower Arkansas River.[2] The French and Spanish traded with the Quapaw for years, and the post was of strategic value to the French, Spanish, and Americans. It was designated as the first capital of the Arkansas Territory in 1819, but lost that status to Little Rock in 1821. During the years of fur trading, Arkansas Post was protected by a series of forts. The forts and associated settlements were located at three known sites and possibly a fourth, as the waterfront area was prone to erosion and flooding.[2][3]

| Arkansas Post | |

|---|---|

| Native name French: Poste de Arkansea | |

| |

| Nearest city | Gillett, Arkansas, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 34°1′8″N 91°20′56″W |

| Area | 757.51 acres (306.55 ha) |

| Elevation | 177 feet (54 m) |

| Built | 1686 |

| Built for | Louis XIV of France |

| Restored | February 27, 1929 |

| Restored by | Arkansas General Assembly |

| Visitors | 30,126 (in 2018)[1] |

| Governing body | U.S. National Park Service |

| Website | Arkansas Post National Memorial |

| Official name: Arkansas Post National Memorial | |

| Designated | October 15, 1966 |

| Reference no. | 66000198 |

U.S. National Memorial | |

| Designated | July 6, 1960 |

| Designated by | President Dwight D. Eisenhower |

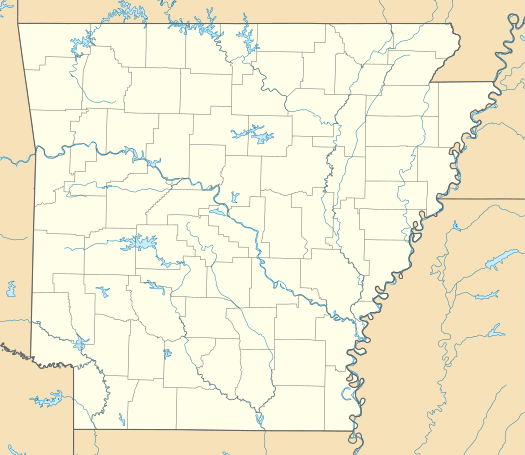

Location of Arkansas Post in Arkansas  Arkansas Post (the United States) | |

The land encompassing the second (and fourth) Arkansas Post site (Red Bluff) was designated as a state park in 1929. In 1960 about 758 acres (307 ha) of land at the site were protected as a National Memorial and National Historic Landmark;[4] it commemorates the history of several cultures and time periods: the Quapaw, the French settlers who inhabited the small entrepôt as the first Arkansans, Spanish rule, an American Revolutionary War skirmish in 1783, the first territorial capital of Arkansas, and an American Civil War battle in 1863.[3][5]

Three archeological excavations have been conducted at the site, beginning in the 1950s. Experts say the most extensive cultural resources at the site are archeological, both for the 18th and 19th-century settlements, and the earlier Quapaw villages.[3] Due to changes in the river and navigation measures, the water level has risen closer to the height of the bluffs, which used to be well above the river. The site is now considered low lying. Erosion and construction on the river have resulted in the remains of three of the historic forts being under water in the river channel.[3]

History

French ownership (1686–1763)

First location

The Arkansas Post was founded in the summer of 1686 by Henri de Tonti, Jacques Cardinal, Jean Couture, and four other Frenchmen as a trading post near the site of a Quapaw village named Osotouy, about 35 miles upriver from the strategically significant confluence of the Arkansas with the Mississippi River. The post was established on land given to De Tonti for his service in René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle's 1682 expedition. The agreement with the local Quapaw consisted of trading French goods for beaver furs, although this arrangement did not yield much profit, as the Quapaw had little interest in hunting beaver. Even so, trade and friendly relations with the Quapaw and other local native peoples, such as the Caddo and Osage, were integral to the post's survival for most of its operations.[2]

The French settlers initially called the post Aux Arcs ("at the home of the Arkansas," as Arkansea was the Algonquian name for the Quapaw used by the Illinois and related tribes). The first structures erected at the site were a simple wooden house and fence. The small settlement was the first permanent French holding west of the Mississippi and the first European settlement in the Lower Mississippi Valley.[6] There the French conducted the first documented Christian services in Arkansas.[2]

The importance of the post was fully realized in 1699, when King Louis XIV began to invest more resources into French Louisiana. John Law's Mississippi Company made a venture from 1717 to 1724 recruiting German settlers to turn the surrounding area into a major agricultural hub. The plan was to grow crops on the lower Arkansas for trade with Arkansas Post, New Orleans, and French Illinois. About 100 slaves and indentured servants were brought to the area as workers, and land grants were offered to German settlers. However, this project failed when the company withdrew from Arkansas Post due to the burst of the Mississippi Bubble. Most of the slaves and indentured servants were relocated elsewhere along the Lower Mississippi, but a few remained in or near the post, becoming hunters, farmers, and traders.[2]

By 1720, the post had lost much of its significance to the French because of the lack of profit in trading with the Quapaw, and the population was low.[3] In 1723, the post was occupied by thirteen French soldiers and Lieutenant Avignon Guérin de La Boulaye was the commander. Father Paul du Poisson was priest at the post from July 1727 until his death in 1729. The post was significantly expanded in 1731, when its new commander, First Ensign Pierre Louis Petit de Coulange, built a barrack, a powder magazine, a prison, and a house for himself and future commanders.[2]

On May 10, 1749, during the Chickasaw Wars, the post experienced its first military engagement. Chief Payamataha of the Chickasaw attacked the rural areas of the post with 150 of his warriors, killing and capturing several settlers.[2]

The site of this first post is believed to be near what is now called the Menard-Hodges Site, located about 5 miles (8.0 km) (but about 25 miles (40 km) by road) from the Arkansas Post Memorial. This property, like the memorial a National Historic Landmark, is owned by the National Park Service, but is undeveloped.[7]

Second location (Red Bluff)

As a result of the Chickasaw raid and continued threats of attack, Ensign Louis Xavier Martin de Lino, the commander at the time, moved the post upriver, further from the Chickasaw territory east of the Mississippi, and closer to the Quapaw villages, the post's main trading partners. This new location, about 45 miles from the mouth of the Arkansas, was called Écores Rouges (Red Bluff), at "the heights of the Grand Prairie" and was situated on a bend in the river, on higher ground than the previous location.[2]

In 1752, Captain Paul Augustin Le Pelletier de La Houssaye, the next commander, rebuilt the post's important structures such as the barrack, prison, and powder magazine. In addition to these structures, he expanded the commander's house to include a chapel and quarters for the priest. He added a storehouse, hospital, bake house, and latrine. To protect the post's new buildings, he erected a stockade eleven feet in height.[2][3]

Third location

In 1756, after the start of the Seven Years' War, Captain Francois de Reggio moved the post to a location only 10 miles from the Mississippi in order for the post to better respond to British and Chickasaw attacks. Whereas the first two locations had been on the Arkansas' north bank, this one was on the south. The layout of this post was generally similar, containing the usual important structures protected by a stockade.[2]

Spanish ownership (1763–1802)

After the British defeated the French in the Seven Years' War and gained most of their North American territories, France ceded the area west of the Mississippi to Spain in exchange for the British gaining land in Florida.[2] The post was officially ceded to Spain in 1763, but Spain did not take up administration of the post until 1771.[3]

Initially the Spanish kept the post at the third site and built the first Fort Carlos to defend it.[8] The majority of the post's population remained French even after it was ceded to Spain. This complicated Spain's effort for diplomacy. In 1772, Commander Fernando de Leyba was ordered to assert dominance over the local French and to reduce the amount of feasts and gifts for the local Quapaw, as it was costing the colonial government too much. This brought the Spanish close to hostilities with the Quapaw, but eventually Commander Leyba conceded the goods and conflict was avoided.[2]

Fourth location (Red Bluff)

In 1777 and 1778, the post was partially inundated by flood waters. The garrison captain, Balthazar de Villiers, wrote to the Spanish governor of Louisiana, Bernardo de Gálvez, requesting the post be moved upriver. De Villiers cited annual flooding and the long distance from the local Quapaw villages as concerns.[8]

In the fall of 1778 Colonel David Rogers and Capt. Robert Benham made a stop here while on their to meet with Gálvez to convince him that Spain should enter the war with England.

Gálvez gave permission for de Villiers to move the post back to the site of the second French post, 36 miles upriver at Red Bluff, and in 1779, the post was relocated. The colonists hoped the settlement would be less flood-prone.[8] Fort San Carlos III was built here in July 1781, near the former Le Houssaye fort. It consisted of several small buildings surrounded by a stockade.

During the last two decades of the 18th century, several Americans settled the post, building a separate American village on the bluffs north of the river, nearer to the Quapaw villages. Many of these settlers arrived as refugees from the Revolutionary War.[3]

On 17 April 1783, James Colbert, a British Indian trader and partisan, conducted a raid with fellow partisans and their Chickasaw allies against Spanish forces controlling Arkansas Post. This was part of a small British campaign against the Spanish on the Mississippi River during the American Revolutionary War, when power was shifting in North America. The Spanish defended it with their soldiers, Quapaw allies, and settlers acting as Indians to scare off the partisans.[6][8][9]

With deterioration of Fort San Carlos due to river action cutting away at the bluff, the Spanish chose a site about half a mile from the waterfront, where in the 1790s they built Fort San Estevan de Arkansas. The complex included a house, large barracks, storehouse and kitchen, all surrounded by a stockade.[3][8]

Second French ownership (1802–1804)

Although Spain ceded Louisiana and the Arkansas Post to France in 1800, no French officials were sent to administrate the post. The Spanish garrison remained to oversee the post until it was sold to the United States.[2]

United States ownership (1804–present)

In 1804, Arkansas Post became a part of the United States as a result of the Louisiana Purchase from France. By the time the post was sold, it contained 30 houses in rows along two perpendicular streets. These were inhabited mostly by the post's French population. The American settlers had remained in the separate village north of the post, although further American settlement began after purchase by the United States, and American buildings were built in the main part of the post alongside the French and Spanish ones. The post was guarded by Fort San Estevan, renamed Fort Madison by the new American administration. Fort Madison was in use until 1810 when it was abandoned due to erosion and flooding.[3]

In 1805, a trading house was built at the north end of the post, operated by Jacob Bright. The location became a major frontier post for travelers heading west, with explorers like Stephen Harriman Long and Thomas Nuttall passing through.[3]

Arkansas Post was selected to be the capital of Arkansas County in 1813, and in 1819, it was selected as the first capital of the new Arkansas Territory. It became the center of commercial and political life in Arkansas. The territory's first newspaper, the Arkansas Gazette, was founded in 1819 at the post by William E. Woodruff. A tavern owned by William Montgomery was operated at the post from 1819 to 1821, and this structure also served as the meeting place for the first Arkansas Territorial General Assembly in February 1820. The tavern was located in the same building as Jacob Bright's trading house. During its period as territorial capital, the post grew substantially, and two towns were established near it.[3]

Gradually, settlement drifted further into the Arkansas River valley, and Little Rock became the territory's dominant settlement. When the territorial capital was moved there in 1821, the territory's major businesses and institutions moved as well, and Arkansas Post lost much of its importance.[2]

The settlement continued to be somewhat important as a river town through the 1840s. A French entrepreneur, Colonel Frederick Notrebe, came to dominate commercial life at the post. His establishment consisted of a house, a store, a brick store, a warehouse, a cotton gin, and a press. In the 1840s, the post was further expanded with several buildings, including one to serve as the Arkansas Post Branch of the State Bank of Arkansas. By the 1850s, the post was in a period of decline and the population shrank significantly.[3]

A well and cistern were built at the post in the early 1800s and remain intact at the memorial site to this day.[3]

Confederate control (1861–1863)

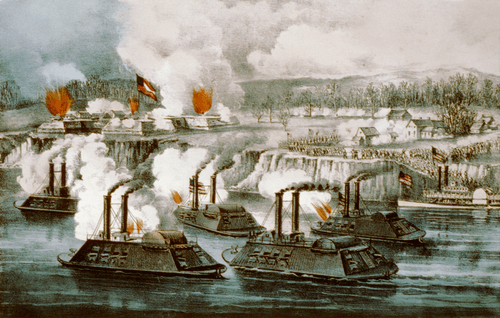

During the American Civil War, the post remained an important strategic site militarily. In 1862, the Confederate Army constructed a massive defensive earthwork known as Fort Hindman, named after Confederate General Thomas C. Hindman. It was located on a bluff 25 feet above the river on the north bank, with a mile view up and downriver. It was designed to prevent Union forces from going upriver to Little Rock, and to disrupt Union movement on the Mississippi. On January 9–11 of 1863, Union forces conducted an amphibious assault on the fortress backed by ironclad gunboats as part of the Vicksburg Campaign. Because the Union forces outnumbered the defenders (33,000 to 5,500), they won an easy victory and captured the post, with most of the Confederate garrison surrendering. During the battle, the artillery bombardments destroyed or severely damaged both the fort and the civilian areas, after which Arkansas Post lost any status it had retained since being replaced as the territorial capital, and became a mostly rural area.[3][10]

The Union victory relieved much of the harassment by Confederate forces on the Mississippi and contributed to the eventual victory at Vicksburg.[3]

During the period of Confederate control, the state bank building was used as a hospital. Parts of the Confederate road, trenches, and artillery positions built at the post during this era are still visible at the memorial site.[3]

Modern commemorations

The Arkansas Post National Memorial is a 757.51-acre (306.55 ha) protected area in Arkansas County, Arkansas in the United States. The National Park Service manages 663.91 acres (268.67 ha) of the land, and the Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism manages a museum on the remaining grounds. The former site of Arkansas Post was made into a state park in 1929. The park began with 20 acres donated by Fred Quandt, a descendant of German immigrants whose family still lives in Arkansas. In the following years, additional acreage was acquired and numerous improvements made with the support of Works Progress Administration labor. It is located on a peninsula formed by the former channel of the Arkansas River.

In 1956–1957, Preston Holder conducted the first archeological excavations at the site. His team found remains of the eighteenth-century French colonial village within the area of the current memorial. The trenches discovered there were later identified as traditional French colonial residential building patterns of poteaux-en-terre.[11] By this time, the remains of the 1752 La Houssaye fort, 1779 Fort San Carlos III, 1790s Fort San Estevan, and Fort Hindman were all under water in the former Arkansas River channel, an area then used as a navigation lake. No archeological evidence remains for those forts because of the erosion.[3]

On July 6, 1960 the site was designated a National Memorial, and a National Historic Landmark on October 9, 1960.[3][12][13] As with all National Historic Landmarks, Arkansas Post was administratively listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966.[14]

In 1964 the National Park Service undertook some partial reconstruction of colonial remains on site, including the 1779 Fort San Carlos III built by the Spanish. Additional archeological excavations of the colonial settlement were done for the National Park Service in 1966 and 1970–1971. Nineteenth-century buildings identified include the state bank and residences. Most of the residences were built in a French or Spanish colonial style, although a house's architecture varied based on the resident's culture. Also discovered in various excavations were thousands of ceramic shards. John Walthall, the state archeologist for Arkansas, said in the 1990s that the archeological resources constitute the most valuable cultural resources within the area of the memorial, including nearly unexplored Quapaw settlements, as well as the 18th- and 19th-century European and American settlements. Archeological ventures have generally been more successful in the more northerly portion of the historic site because it was less prone to erosion and flooding. No physical traces remain of the post's historical waterfront because of such erosion.[3]

Over time, the Arkansas River eroded the settlement away. This portion of the river was the site of the Civil War fort

Over time, the Arkansas River eroded the settlement away. This portion of the river was the site of the Civil War fort Partial reconstruction of the Revolutionary War era fort

Partial reconstruction of the Revolutionary War era fort Today, a sidewalk and interpretive signs lead visitors through the historical town site

Today, a sidewalk and interpretive signs lead visitors through the historical town site

See also

References

- "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved June 13, 2019.

- DuVal, Kathleen (May 9, 2011). "Arkansas Post". Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture. The Butler Center. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- House, John H. (December 3, 1998). "Arkansas Post" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places Registration. National Park Service.

- "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- "History & Culture". National Park Service. November 2, 2006. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- "Arkansas Post National Memorial", American Latino Heritage, Travel Itineraries, National Park Service, accessed 8 June 2013

- "The Weathervane, Volume 2, Number 2 (2006)". National Park Service. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- Edwin C. Bearss (November 1974). "Special History Report: The Colbert Raid" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- David Sesser (September 14, 2010). "Colbert Raid". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- Mark K. Christ (December 31, 2010). "Battle of Arkansas Post". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- John Walthall, "An Analysis of Late Eighteenth-Century Ceramics from Arkansas Post at Ecores Rouges", Southeastern Archeology 10:98–113

- "Arkansas Post". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. September 25, 2007.

- "Arkansas Post—Accompanying 1 photo, exterior, undated" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places Registration. National Park Service. December 3, 1998.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arkansas Post. |

- Government

- Official website

- Arkansas Post at the American Battlefield Protection Program

- Arkansas Post Museum at Arkansas State Parks (arkansasstateparks.com)

- General information

- Arkansas Post National Memorial at Encyclopedia of Arkansas

- Arkansas Post National Memorial at the National Park Foundation

- Colonial Arkansas Post Ancestry at the University of Arkansas

- Works by or about Arkansas Post at Internet Archive