Fort Carlos

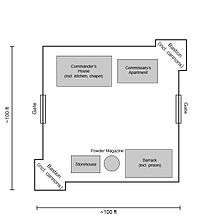

Fort San Carlos, known later as Fort Carlos, was the name given to a series of at least two simple stockade forts built during the Spanish ownership of Arkansas Post (1763-1789) with the purpose of protecting the trading post from attack. Both incarnations of the fort were the focus of the post, containing the commander's house, barrack, commissary's apartment, provision storage, and powder magazines.[1] The forts were named for Charles (Carlos) III, who was King of Spain in the latter half of the 18th century during which Spain possessed the post.[2][3] The forts were located about 10 miles from the mouth of the Arkansas River, and at a second location about 35 miles upriver, on the north bank. The remains of all the Spanish forts are now inundated by the river, due to erosion of riverbanks, changing river course, and federal construction for navigation.[4]

Fort Carlos II

When the Spanish took control of the Arkansas territory in 1763, they decided to move their garrison from the French colonial settlement of Arkansas Post closer to the mouth of the Arkansas River. This fort was built by 1768 about 10 miles from the mouth, as it was visited that year by British Captain Philip Pittman. He described it as consisting of:

...a quadrangular form; the sides of the exterior polygon are about one hundred and eight feet, and one three pounder is mounted in the flanks and faces of each bastion. The buildings within the fort are, a barrack with three rooms for the soldiers, commanding officer‟s house, a powder magazine, and a magazine for provision, and an apartment for the commissary, all of which are in a ruinous condition. The fort stands about two hundred yards from the water-side, and is garrisoned by a captain, a lieutenant, and thirty French soldiers, including serjeants and corporals.[1]

In both 1777 and 1778, the Arkansas Post was partially inundated during spring flooding. The captain, Balthazar de Villiers, wrote to the Spanish governor of Louisiana, Bernardo de Gálvez, requesting the post be moved upriver. De Villiers cited annual flooding and the long distance from the local Quapaw villages, where they were trading, as concerns. Gálvez gave permission for de Villiers to abandon the current site and move the post back to the site of the French settlement, about 35 miles upriver.[1] There is no mention of the fort remaining in use after this abandonment. Its remains are believed to have been eroded into the river.

Fort Carlos III

This was the fort built in July 1781 at the new location of the post.[5] The discovery of the intention by partisans to capture the post in that month prompted the fort's construction. Captain de Villiers wrote Governor Gálvez on July 11 regarding his intention to erect a new fort:

the King will have here a solid post capable of resisting anything which may come to attack it without cannon.[6]

It was located on the north side of the river, approximately half a mile upriver from the post's habitant coast. This new location was on the Grand Prairie, a bluff above the flood plain.[7] De Villiers described the fort's stockade as consisting of:

...red oak stakes thirteen feet high, with diameters of 10 to 15 or 16 inches, split in two and reinforced inside by similar stakes to a height of six feet and a banquette of two feet.[8]

He also wrote that the stockade enclosed all

necessary places, including a house 45 feet long and 15 feet wide, and a storehouse, both serving to lodge my troops, and around several smaller buildings.[9]

In addition, the fort consisted of two gates on opposite sides and two bastions at opposite angles of the fort, each mounted with 3 1/2-inch brass cannons. Embrasures in the stockade, which were covered with bullet-proof sliding panels, were made for the cannons and swivel guns.[10]

Lieutenant Luis de Villars became acting commander at the post in April 1782 after Captain de Villiers became too ill to perform his duties.[11] Captain Jacobo Dubreuil took over as commander of the post on January 5, 1783,[12] and added a bastion at one angle of the fort.[13] De Villars remained at the fort as second-in-command, despite orders from the Spanish governor of Louisiana to leave. The fort was the focus of the Colbert Raid during the American Revolutionary War,[14] during which it was a place of refuge for the local women and children.[15]

The side of the fort closest to the river was slowly destroyed by erosion and flooding in the years of 1787 through 1789. After Ignacio Delinó took control of the post in 1790, he built a new fort about a half mile back from the river, Fort San Estevan, to replace the ruined Fort Carlos. By February 1793, the site of the former fort was entirely eroded into the river.[16]

When the United States took over the territory in 1803 by the Louisiana Purchase, it renamed Fort San Estevan as Fort Madison. It abandoned it after 1810. Erosion continued and eventually overtook Fort San Estevan/Madison. Today, the remains of all the former Spanish forts are inundated beneath Horseshoe Lake (Post Bend), the former channel of the Arkansas River now used as a navigation lake.[4][17]

References

- "Special History Report: The Colbert Raid (page 10)" (PDF). National Park Service (Edwin C. Bearss, John Garner). November 1974. Retrieved June 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Arkansas Post". Encyclopedia of Arkansas (Kathleen DuVal). February 6, 2013. Retrieved June 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Arkansas Post National Memorial - Gillett, Arkansas". National Park Service. Retrieved June 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - House, John H. (1998-12-03). "Arkansas Post" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places Registration. National Park Service.

- "Special History Report: The Colbert Raid (page 21)" (PDF). National Park Service (Edwin C. Bearss). November 1974. Retrieved June 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Special History Report: The Colbert Raid (page 22)" (PDF). National Park Service (Edwin C. Bearss). November 1974. Retrieved June 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Special History Report: The Colbert Raid (pages 12, 13, 21)" (PDF). National Park Service (Edwin C. Bearss). November 1974. Retrieved June 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Special History Report: The Colbert Raid (pages 22, 55)" (PDF). National Park Service (Edwin C. Bearss). November 1974. Retrieved June 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Special History Report: The Colbert Raid (pages 22, 57)" (PDF). National Park Service (Edwin C. Bearss). November 1974. Retrieved June 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Special History Report: The Colbert Raid (pages 55-56)" (PDF). National Park Service (Edwin C. Bearss, John Garner). November 1974. Retrieved June 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Special History Report: The Colbert Raid (page 40)" (PDF). National Park Service (Edwin C. Bearss). November 1974. Retrieved June 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Special History Report: The Colbert Raid (page 33)" (PDF). National Park Service (Edwin C. Bearss). November 1974. Retrieved June 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Special History Report: The Colbert Raid (page 56)" (PDF). National Park Service (Edwin C. Bearss). November 1974. Retrieved June 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Colbert launches raid on Fort Carlos, Arkansas". History Channel website, 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-08-26. Retrieved June 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Special History Report: The Colbert Raid (pages 43, 48)" (PDF). National Park Service (Edwin C. Bearss). November 1974. Retrieved June 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Special History Report: The Colbert Raid (pages 50, 52, 53)" (PDF). National Park Service (Edwin C. Bearss). November 1974. Retrieved June 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Special History Report: The Colbert Raid (page 8)" (PDF). National Park Service (Edwin C. Bearss). November 1974. Retrieved June 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help)