Arianiti family

The Arianiti were an Albanian noble family that ruled large areas in Albania and neighbouring areas from the 11th to the 16th century.[3] Their domain stretched across the Shkumbin valley and the old Via Egnatia road and reached east to today's Bitola.[4]

| Arianiti family | |

|---|---|

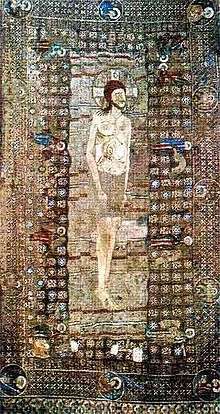

Crest of Arianiti [1] | |

| Current region | Shkumbin valley, old Via Egnatia road, eastwards up to Bitola |

| Place of origin | Central Albania |

| Members |

|

| Connected families | Komnenos Kastrioti family |

Names

The first attested surname of the family in various forms is Ar(i)aniti, which was also used as a personal name.[5] In documents contemporary to its members Araniti is the most prevalent form, from which almost all placenames of the areas of their domains that were named after them derive. Arianiti, a rare form from the first definite documentations of the family in the late 13th and early 14th century to the extinction of its male line in the mid-16th century, became prominent in early modern era works and eventually reached a common surname status in historical discourse. The etymology of the surname is unclear; it may ultimately derive from the Indo-European word arya (noble), derivations of which can be found as placenames, denonyms or ethnonyms in many areas ranging from western Europe to Iran and northern India (cf. Areiane, the Greek name for eastern Iran) or the Albanian word arë (field).[5][6][7]

If the placenames in Albania that are akin to arya are related to the Arianiti family and don't derive from the rule of the family over those areas, their presence as a clan could be traced back to the late 9th century in the theme of Dyrrhachium, however, its members until the late 13th century are disputed as the surname appears to have been adopted by unrelated to each other low-born individuals after they came to positions of power. One theory links the surname with the Illyrian tribe of the Arinistae/Armistae that lived around Dyrrhachium in the Hellenistic and Roman era.[5]

A secondary surname used by the Arianiti family since the 14th century was Komneni surname, which derives from the Byzantine imperial house of Komnenos. The first of the family to bear was possibly married to a female descendant of Golem of Kruja and could be related to a Comneni Budaresci princeps, who lived around 1300 in central Albania, although any connection to any member can't be verified as all Arianitis used Komneni as a second surname by the mid to late 14th century as a means to strengthen their noble status and territorial claims.[8]

The surname Shpata appears in Latin sources of the late 14th and early 15th century in reference to a Comin Spata, who could possibly be Komnen Arianiti, father of Gjergj Arianiti, who was also mentioned in contemporary documents as Aranit Spata. It is unclear whether the Arianitis adopted it through intermarriage with the Shpata family of central Albania or as a toponymic that derives from the region of Shpat, which they held in the Middle Ages. If the intermarriage theory is correct, the adoption of the surname must have happened in the 14th century.[9]

Golemi was used as a byname by some members of the Arianiti family. It first appears in a 1452 document of the chancellery of Alfonso V of Aragon, where Gjergj Arianiti is mentioned as Aranit Colem de Albania, while Marin Barleti mentions him as Arianites Thopia Golemus. The word itself may come from the Slavic golem (grand) or as a distortion of the name Gulielm (the Albanian version of William). Attempts to relate it to Golem of Kruja or personalities named Gulielm Arianiti are resultless as no archival evidence exists.[10]

History

David Arianites is generally considered to be the first member of the Arianiti clan that is attested in historical documents, although the connection to the late 13th century Arianiti family can't be verified due to lack of sources.[4][6][11] As attested in the works of George Kedrenos, in the 1001–1018 period he served the Byzantine Emperor Basil II as strategos of Thessalonica, and later strategos of Skopje. David Arianites fought against the Bulgarians in Strumica, Skopje and the area of Skrapar. Constantine Arianites, a son or close relative, is also mentioned in the years 1049-1050 as being in the military service of the Byzantine Empire against the Pechenegs.[11] Other members of the 11th and 12th centuries may include a Johannes Carianica mentioned by William of Tyre.

The first undisputed member of the family is sebastos is Alexius Arianiti mentioned in 1274 in an agreement between Charles I of Naples and some Albanian noblemen, who swore allegiance to the Kingdom of Albania.[12] The Arianiti last name has also been mentioned in other 14th century documents: In 1304 two documents, one from Philip I, Prince of Taranto, and the other from Charles II of Naples between several names of Albanian noble families, to whom are recognized prior held privileges, include the name of the Arianiti family. In a 1319 letter, Pope John XXII sent to some Albanian nobles, the name of protolegator Gulielm Arianiti (Guillermo Aranite protholegaturo) is included. In the Epitaph of Gllavenica, embroidered in 1373, the name of George Arianiti, the embroiderer is documented.[4]

Not necessarily all the Arianiti people mentioned in various 11-14th century sources belong to the same family tree, however from them it is safe to assume that the Arianiti family was an important noble family of Medieval Central Albania. The importance of such family stemmed from the possession and control of important segments of the Royal Road (Via Egnatia) which served multiple convoys trading grain, salt and other products. The Arianiti family must have had the collaboration of the Pavle Kurtik, whose domain were in the provinces middle course of Shkumbin, and with župan Andrea Gropa, ruler of the city of Ochrid. The dominant position of the fortress of Ochrid, on the whole area of a very rich lake with high quality fish, had made his possession was the focus of political and military actions of the gods of the areas nearby.[4]

Arianiti's political activity is better reflected in 15th century documents, when following Ottoman conquests, they lost the rich eastern regions of their dominions and began to pursue more active and aggressive foreign policies, especially since 1430 when Gjergj Arianiti had a series of victories over the Ottoman armies.[4]

The Arianiti family members are several times mentioned by their last name along other last names, which include Komneni, Komnenovich, Golemi, Topia, Shpata, and Çermenika, as well as nobility titles. The inherited titles and the other names testify that the Arianiti had established family ties with other noble families, including those of the Byzantine Empire, as indicated by the surname Komneni/Komnenos. The Arianiti family also had their coat of arms and other heraldry signs. The double headed eagle emblem was on their heraldic symbols. A document shows that Gjergj Arianiti had commissioned his flag to be designed in Ragusa.[4]

The genealogical tree Arianiti cannot be built exactly, since the earliest periods, when they are first mentioned. According to Marin Barleti and Gjon Muzaka Gjergj Arianiti's father was Komnen Arianiti. Komnen Arianiti had married the daughter of Nikolle Zaharia Sakati, ruler of Budva. Komnen Arianiti had three sons (Gjergj, Muzaka, and Vladan), and one daughter who married Pal Dukagjini.[4]

Muzaka Arianiti had one son, Moisi Arianiti, a warrior that fought the Ottoman Empire along Skanderbeg. Moisi Arianiti is primarily known as Moisi Golemi. Moisi Golemi had married Zanfina Muzaka, first wife of Muzaka Topia. Muzaka Topia, after his marriage with Zanfina Muzaka, married Skanderbeg's sister, and oldest daughter of Gjon Kastrioti, Maria Kastrioti.[4]

The younger brother of Gjergj Arianiti, Vladan, married the daughter of Gjon Kastrioti, Angjelina, long before that Skanderbeg appeared on the top of the Albanian war against the Ottoman Empire. Their son, Muzaka (described as Muzaka of Angjelina, in order to distinguish him from his uncle) participated in the creation of the League of Lezhë in 1444.[4] After Arianiti family together with Dukagjini family left the League of Lezhë in 1450, members of Dukagjini family concluded a peace with Ottoman Empire and started their actions against Skanderbeg.[13] It looked that Skanderbeg had some success to keep Arianiti family near him by marrying Donika (Andronika[14]) Arianiti, daughter of Gjergj Arianiti, in April 1451.[13]

The political and military activities of the great son of Komnen Arianiti, Gjergj, gave the Albanian noble family name of Arianiti a particular weight in Albania's political life.[4]

Gjergj Arianiti married Maria Muzaka with whom he had eight daughters. Her death caused him to marry the Italian noblewoman Despina (or Petrina) Francone, daughter of the governor of Lecce in the Kingdom of Sicily. They had three sons (Thoma, Kostandin and Arianit) and a daughter.[4]

The possessions of the Arianiti family have changed over time with expansion and contractions, but in general, the Arianiti enjoyed a special position in the economic and political life of Albania and in the relationships with different regions of country and their political forces. Proof of this are the several marriages of the Arianiti's descendants to the Kastrioti and Muzaka families, as well as Dukagjini, and also to Serb despot Stefan Brankovic, who married Gjergj Arianiti's daughter, Angjelina Arianit Komneni, later Saint Angelina of Serbia.[4]

The eastern extension of the state of Gjergj Arianiti included Manastir and Florina, and most of the areas around the Ohrid Lake from which a large income from fishing and fish exporting was obtained. The Arianiti also owned the Sopotnica castle (Svetigrad), later named by the Ottomans Demir Hisar.[4]

After initial resistance to the Ottomans, they become one of noble families, like i.e. Zenebishi and Muzaka, who were converted to Islam and appointed to positions within Ottoman military and feudal hierarchy.[15]

References

- Heraldika Shqiptare, Gjin Varfi, 2000, ISBN 978-9992731857

- [https://www.jstor.org/stable/41298891?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents Nelson H. Minnich, "Alexios Celadenus: A Disciple of Bessarion in Renaissance Italy", Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques Vol. 15, No. 1 (1988) p. 53]

- Fishta et al. 2005, p. 402

- Anamali 2002, pp. 255–7

- Shuteriqi 2012, pp. 20–9

- Schramm 1994

- Polemis 1968, p. 103

- Shuteriqi 2012, pp. 29–37

- Shuteriqi 2012, pp. 44–48

- Shuteriqi 2012, pp. 38–42

- Shuteriqi 2012, pp. 50–1

- Shuteriqi 2012, pp. 51–53

- Frashëri 1964, p. 78

- Schmitt Oliver Jens, Skandermbeg et les sultans, Turcica, 43 (2011) p. 71.

- Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2010). Religion und Kultur im albanischsprachigen Südosteuropa (in German). Peter Lang. p. 56. ISBN 978-3-631-60295-9.

Muslimisch gewordene Angehörige der Familien Muzaki, Arianiti und Zenebishi, die vorher am Abwehrkampf gegen die Türken beteiligt gewesen waren, wurden in das Militärlehenssystem eingegliedert und erhielten Posten in der ...

Sources

- Babinger, Franz (1960). Das Ende der Arianiten (in German). Munich: Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften. OCLC 876478494.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frashëri, Kristo (1964). The history of Albania: a brief survey. Shqipëria: Tirana. OCLC 230172517. Retrieved 23 January 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anamali, Skënder (2002). Historia e popullit shqiptar në katër vëllime (in Albanian). I. Botimet Toena. OCLC 52411919.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harris, Jonathan (2013), 'Despots, emperors and Balkan identity in exile’, Sixteenth Century Journal 44, pp. 643–61

- Shuteriqi, Dhimitër (2012). Zana Prela (ed.). Aranitët: Historia- Gjenealogjia -Zotërimet. Toena. ISBN 978-99943-1-729-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schramm, Gottfried (1994). Anfänge des albanischen Christentums: die frühe Bekehrung der Bessen und ihre langen Folgen. Rombach. ISBN 9783793090830. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

Ja, schon früher war einer arbanitischen Familie offenbar der Aufstieg in die Reichsaristokratie gelungen, wenn mit Recht aus dem Namen der Familie der Arianitai auf albanischen Ursprung geschlossen wurde. Der Patrikios David Arianites sah sich ...

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Polemis, Demetrios I. (1968). The Doukai: A Contribution to Byzantine Prosopography. London, United Kingdom: The Athlone Press. p. 103.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fishta, Gjergj; Elsie, Robert; Mathie-Heck, Janice; Centre for Albanian Studies (London, England) (2005). The highland lute: (Lahuta e malcís) : the Albanian national epic. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-118-2. Retrieved 9 December 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)