Apalachicola, Florida

Apalachicola (/æpəlætʃɪˈkoʊlə/) is a city in Franklin County, Florida, United States, on the shore of Apalachicola Bay, an inlet of the Gulf of Mexico. The population was 2,231 at the 2010 census.[5] Apalachicola is the county seat of Franklin County.[6]

Apalachicola, Florida | |

|---|---|

Dixie Theatre (2008) | |

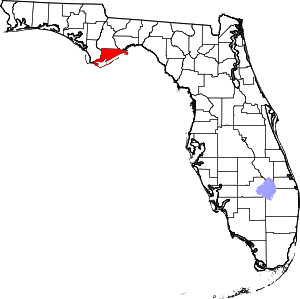

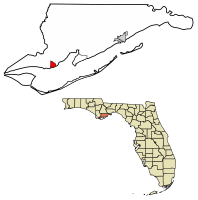

Location within Franklin County and Florida | |

Apalachicola, Florida Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 29°43′31″N 84°59′33″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Florida |

| County | Franklin |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Van Johnson |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.63 sq mi (6.80 km2) |

| • Land | 1.93 sq mi (4.99 km2) |

| • Water | 0.70 sq mi (1.81 km2) |

| Elevation | 13 ft (4 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 2,231 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 2,354 |

| • Density | 1,222.86/sq mi (472.21/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 32320, 32329 |

| Area code(s) | 850 |

| FIPS code | 12-01625[3] |

| GNIS ID | 0277920[4] |

| Website | cityofapalachicola.com |

History

Etymology

"Apalachicola" comes from the Apalachicola tribe and is a combination of the Hitchiti words apalahchi, meaning "on the other side", and okli, meaning "people". In original reference to the settlement and the subgroup within the Seminole tribe, it probably meant "people on the other side of the river".[7][8] Many inhabitants of Apalachicola have said the name means "land of the friendly people".[9]

Between the years 1513 and 1763 the area that now includes the town of Apalachicola was under Spanish jurisdiction as part of Spanish Florida, however, the Spanish, based out of Pensacola, never ventured as far east as the Apalachicola river and the area remained unsettled and unexplored during the duration of Spain's first occupation of Florida. The only inhabitants of the area during that entire time were the Apalachee, Miccosukee and Timucua tribes. In the 1750s during the French and Indian War the British captured the Spanish colony of Cuba, however, because Cuba was a prized possession for the Spanish and Florida was mostly unused backwater, the Spanish traded Florida to the British in return for regaining Cuba. Between the years 1763 and 1783 the area that is now Apalachicola fell under the jurisdiction of British West Florida. A British trading post called "Cottonton" was founded at this site on the mouth of the Apalachicola River. In 1783, British West Florida was transferred to Spain, however, the trading post (and its British inhabitants) remained and continued facilitating trade along the Apalachicola River (which was connected to the trading network along the Chattahoochee River). Gradually after acquisition by the United States and related development in Alabama and Georgia, it attracted more permanent European-American residents. In 1827, the town was incorporated as "West Point". Apalachicola received its current name in 1831, by an act of the Legislative Council of the Territory of Florida.[10][11]

Trinity Episcopal Church was incorporated by an act of the Legislative Council of the Territory of Florida on February 11, 1837. The building was one of the earliest prefabricated buildings in the United States. The framework was shipped by schooner from New York City and assembled in Apalachicola with wooden pegs.

In 1837, a newspaper at Apalachicola boasted that the town's business street along the waterfront "had 2,000 feet [600 meters] of continuous brick stores, three stories high, 80 feet [25 meters] deep, and all equipped with granite pillars."[12]

Botanist Alvan Wentworth Chapman settled in Apalachicola in 1847. In 1860, he published his major work, Flora of the Southern United States. An elementary school was later named in his honor.

On April 3, 1862, during the American Civil War, the gunboat USS Sagamore and the steamer USS Mercedita (relieving the USS Marion) captured Apalachicola.[13] Union forces occupied west Florida during much of the war moved here.

Dr. John Gorrie, discoverer

In 1849, Apalachicola physician Dr. John Gorrie discovered the cold-air process of refrigeration and patented an ice machine in 1850. He had experimented to find ways to lower the body temperature of fever patients.[14] His patent laid the groundwork for development of modern refrigeration and air conditioning, making Florida and the South more livable year round. The city has a monument to him, and a replica of his ice machine is on display in the John Gorrie Museum. The John Gorrie Memorial Bridge, carrying the main road out of Apalachicola, U.S. 98, is named for him.

Transportation

Before railroads reached the region in the later 19th century, Apalachicola was the third-busiest port on the Gulf of Mexico (behind New Orleans and Mobile).[14] Scheduled boats transported passengers and goods up and down the Apalachicola, Chattahoochee, and Flint rivers to Albany and Columbus, Georgia. A paddle steamer, the Crescent City, made a daily round trip to Carrabelle, carrying the mail as well as passengers and freight.

The AN Railway, formerly the Apalachicola Northern Railroad, serves the city.

Originally built in 1935 and rebuilt in 1988, carries U.S. 98 across Apalachicola Bay to Eastpoint.

Geography

Topography

Apalachicola is located in the northwest part of the state, at 29°43′31″N 84°59′33″W,[15] on Apalachicola Bay and at the mouth of the Apalachicola River. U.S. Route 98 is the main highway through town, leading east across the bay to Eastpoint and northwest 59 miles (95 km) to Panama City. Tallahassee, the state capital, is 75 miles (121 km) to the northeast via US 98 and US 319.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 2.6 square miles (6.8 km2), of which 1.9 square miles (5.0 km2) is land and 0.69 square miles (1.8 km2), or 26.67%, is water.[5]

Climate

The climate of Apalachicola is humid subtropical (Köppen Cfa), with short, mild winters and hot, humid summers. The hottest temperature ever recorded in the city was 103 °F (39 °C) on August 15, 1995,[16] and the coldest temperature ever recorded was 9 °F (−13 °C) on January 21, 1985.[16]

| Climate data for Apalachicola, Florida (Apalachicola Regional Airport), 1981–2010 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 80 (27) |

80 (27) |

85 (29) |

90 (32) |

98 (37) |

100 (38) |

102 (39) |

103 (39) |

97 (36) |

93 (34) |

87 (31) |

83 (28) |

103 (39) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 63.1 (17.3) |

66.1 (18.9) |

70.7 (21.5) |

76.6 (24.8) |

84.2 (29.0) |

88.9 (31.6) |

90.6 (32.6) |

89.8 (32.1) |

87.6 (30.9) |

80.8 (27.1) |

73.1 (22.8) |

65.4 (18.6) |

78.1 (25.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 41.6 (5.3) |

44.6 (7.0) |

50.0 (10.0) |

56.3 (13.5) |

64.5 (18.1) |

71.5 (21.9) |

73.6 (23.1) |

73.6 (23.1) |

70.4 (21.3) |

60.5 (15.8) |

51.0 (10.6) |

44.8 (7.1) |

58.5 (14.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 9 (−13) |

19 (−7) |

22 (−6) |

36 (2) |

47 (8) |

48 (9) |

63 (17) |

62 (17) |

50 (10) |

33 (1) |

24 (−4) |

13 (−11) |

9 (−13) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.40 (112) |

4.15 (105) |

5.26 (134) |

3.07 (78) |

2.50 (64) |

5.27 (134) |

7.07 (180) |

8.22 (209) |

6.73 (171) |

4.20 (107) |

3.53 (90) |

3.31 (84) |

57.7 (1,470) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 7.1 | 5.9 | 6.7 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 8.9 | 10.2 | 11.3 | 8.7 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 6.1 | 80.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 187.7 | 188.1 | 250.8 | 296.8 | 327.9 | 304.8 | 278.6 | 262.6 | 251.8 | 261.2 | 212.8 | 187.8 | 3,010.9 |

| Source: NOAA / NWS (extremes 1931–present, sun 1961–1990)[17][16][18] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 1,904 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,129 | −40.7% | |

| 1880 | 1,336 | 18.3% | |

| 1890 | 2,727 | 104.1% | |

| 1900 | 3,077 | 12.8% | |

| 1910 | 3,065 | −0.4% | |

| 1920 | 3,066 | 0.0% | |

| 1930 | 3,150 | 2.7% | |

| 1940 | 3,268 | 3.7% | |

| 1950 | 3,222 | −1.4% | |

| 1960 | 3,099 | −3.8% | |

| 1970 | 3,102 | 0.1% | |

| 1980 | 2,565 | −17.3% | |

| 1990 | 2,602 | 1.4% | |

| 2000 | 2,334 | −10.3% | |

| 2010 | 2,231 | −4.4% | |

| Est. 2019 | 2,354 | [2] | 5.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[19] | |||

As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 2,334 people, 1,006 households, and 608 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,242.1 inhabitants per square mile (479.3/km2). There were 1,207 housing units at an average density of 642.3 per square mile (247.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 63.41% White, 34.92% African American, 0.17% Native American, 0.39% Asian, 0.47% from other races, and 0.64% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.67% of the population.

There were 1,006 households, out of which 23.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.8% were married couples living together, 15.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.5% were non-families. Of all households, 34.7% were made up of individuals, and 14.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.24 and the average family size was 2.87.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 21.9% under the age of 18, 7.0% from 18 to 24, 24.0% from 25 to 44, 26.7% from 45 to 64, and 20.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 43 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $23,073, and the median income for a family was $28,464. Males had a median income of $22,500 versus $18,750 for females. The per capita income for the city was $12,227. About 19.9% of families and 25.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 32.4% of those under age 18 and 15.0% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Apalachicola is still the home port for a variety of seafood workers, including oyster harvesters and shrimpers. More than 90% of Florida's oyster production is harvested from Apalachicola Bay. Every year the town hosts the Florida Seafood Festival. The bay is well protected by St. Vincent Island, Flag Island, Sand Island, St. George Island, and Cape St. George Island.

In 1979, Exxon relocated their experimental subsea production system from offshore Louisiana to a permitted artificial reef site off Apalachicola. This was the first effort to turn an oil platform into an artificial reef.[20]

Arts and culture

Apalachicola is home to the Dixie Theatre,[21] a professional Equity theater which is also a live performance venue. Built in 1912, the theatre was fully renovated beginning in 1996.

Education

Apalachicola is a part of the Franklin County Schools system.[22] As of the 2008–2009 school year, all students, except those attending charter schools, attended the K–12 Franklin County School. Apalachicola Bay Charter School is also located in Apalachicola.

Notable people

- Mary Rogers Gregory, artist

- John Gorrie, inventor of mechanical cooling[23]

- Alvin Wentworth Chapman, botanist

- Richard Heyser, U-2 pilot

- Jimmy Bloodworth, major League baseball player

Literary reference

"Apalachicola" is the title of a poem by E.J. Brady[24]

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001), Apalachicola city, Florida". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "Apalachicola" Archived May 2, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, Florida Heritage Facts, Dept. of Historic Resources

- "Name Origins of Florida Places @ Florida OCHP". dhr.dos.state.fl.us.

- Bay Navigator, Brief History Archived October 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Fabel, Robin F. A. (1988). The Economy of British West Florida, 1763–1783. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. p. 51, 177. ISBN 0-8173-0312-X

- Born, John D. (1968). Governor Johnstone and trade in British West Florida, 1764–1767. Wichita, Kansas: Wichita State University. pp. 19

- Federal Writers' Project (1939), Florida. A Guide to the Southernmost State, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 166

- USS Mercedita history

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 2 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 158–159.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Daily Normal and Record Temperatures in Apalachicola". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2013-11-20.

- "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-05-31.

- "WMO Climate Normals for Apalachicola, Florida 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- Dauterive, Les (2000). "Rigs-to-Reefs policy, progress, and perspective". In: Hallock and French (Eds). Diving for Science ... 2000. Proceedings of the 20th Annual Scientific Diving Symposium. American Academy of Underwater Sciences. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- "Dixie Theatre". www.dixietheatre.com.

- Franklin County Schools website Archived April 24, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Ice and Refrigeration. Nickerson & Collins Company. 1919. p. 235.

- Brady, E.J., (1933), Wardens of the Sea, Sydney, The Endeavour Press, pp.49-50

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Apalachicola, Florida. |

- City of Apalachicola official website

- Apalachicola Bay Chamber of Commerce