Japanese badger

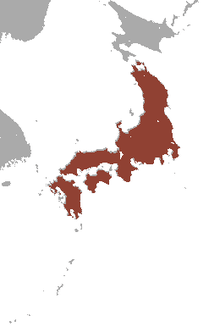

The Japanese badger (Meles anakuma) is a species of carnivoran of the family Mustelidae, the weasels and their kin. Endemic to Japan, it is found on Honshu, Kyushu, Shikoku,[2] and Shōdoshima.[1] It shares the genus Meles with the Asian and European badgers. In Japan it is called by the name anaguma (穴熊) meaning "hole-bear", or mujina (むじな, 狢).

| Japanese badger | |

|---|---|

| |

| At Inokashira Park Zoo, Tokyo | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Mustelidae |

| Genus: | Meles |

| Species: | M. anakuma |

| Binomial name | |

| Meles anakuma Temminck, 1844 | |

| |

| Japanese badger range | |

Description

.jpg)

Japanese badgers are generally smaller (average length 79 cm (31 in) in males, 72 cm (28 in) in females) and less sexually dimorphic (except in the size of the canine teeth) than their European counterparts.[1][3] Tail length is between 14 and 20 cm (5.5 and 7.9 in). This species is similar or mildly larger than the Asian badger. Adults usually weigh from 3.8 to 11 kg (8.4 to 24.3 lb).[4][5] The average weight of female Japanese badgers in one study from the Tokyo area was found to be 6.6 kg (15 lb) while that of males was 7.76 kg (17.1 lb).[6] In the Yamaguchi Prefecture, the average spring weight of female and male Japanese badgers was 4.4 kg (9.7 lb) and 5.7 kg (13 lb).[7] The torso is blunt and limbs are short. The front feet are equipped with powerful digging claws. The claws on hind feet are smaller. The upper coat has long gray-brown hair. Ventral hair is short and black. The face has characteristic black-white stripes that are not as distinct as in the European badger. The dark color is concentrated around the eyes. The skull is smaller than in the European badger.[1]

Origin

The absence of badgers from Hokkaido, and the presence of related M. leucurus in Korea, suggest that the ancestral badgers reached Japan from the southwest via Korea.[1] Genetic studies indicate that there are substantial differences between Japanese and Asian badgers, which were formerly considered conspecific, and that the Japanese badgers are genetically more homogenous.[1]

Habits

Like other members of Meles, Japanese badgers are nocturnal and hibernate during the coldest months of the year.[1] Beginning at 2 years of age, females mate and give birth to litters of two or three cubs in the spring (March–April). They mate again shortly afterwards, but delay implantation until the following February.[1] Japanese badgers are more solitary than European badgers; they do not aggregate into social clans, and mates do not form pair bonds. During mating season, the range of a male badger overlaps with those of 2 to 3 females.[1] Badgers with overlapping ranges may communicate by scent marking.[1]

Habitats

These badgers are found in a variety of woodland and forest habitats.[1]

Folklore

In Japanese mythology, badgers are shapeshifters known as mujina. In the Nihon Shoki, mujina were known to sing and shapeshift as other humans.

Diet

Similar to other badgers, the Japanese badger's diet is omnivorous; it includes earthworms, beetles, berries and persimmons.[1]

Threats

Although it remains common, the range of M. anakuma has shrunk recently.[1] Covering an estimated 29 per cent of the country in 2003, the area had decreased 7 per cent over the previous 25 years.[1] Increased land development and agriculture, as well as competition from introduced raccoons are threats. Hunting is legal but has declined sharply since the 1970s.[1]

In 2017, concern was raised by an upsurge in badger culling in Kyushu. Apparently encouraged by local government bounties and increased popularity of badger meat in Japanese restaurants, it is feared the culling may have reached an unsustainable level.[8][9]

See also

- Mujina, a badger creature from Japanese folklore

References

- Kaneko, Y.; Masuda, R.; Abramov, A.V. (2016). "Meles anakuma". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T136242A45221049. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T136242A45221049.en. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 611. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Kaneko, Y., Maruyama, N. and Kanzaki, N. 1996. Growth and seasonal changes in body weight and size of Japanese badger in Hinodecho, suburb of Tokyo. Journal of Wildlife Research 1: 42-46.

- Tanaka, H. (2006). Winter hibernation and body temperature fluctuation in the Japanese badger, Meles meles anakuma. Zoological science, 23(11), 991-997.

- Yoshimura, K., Shindo, J., & Kageyama, I. (2009). Light and scanning electron microscopic study on the tongue and lingual papillae of the Japanese badgers, Meles meles anakuma. Okajimas folia anatomica Japonica, 85(4), 119-127.

- Kaneko, Y., & Maruyama, N. (2005). Changes in Japanese badger (Meles meles anakuma) body weight and condition caused by the provision of food by local people in a Tokyo suburb. Mammalian Sci, 45, 157-164.

- Tanaka, H. 2002. Ecology and Social System of the Japanese badger, Meles meles anakuma (Carnivora; Mustelidae) in Yamaguchi, Japan. Ph.D Thesis, Yamaguchi University.

- Hornyak, T. (2017-06-09). "Ecologists warn of Japanese badger cull 'crisis'". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22131.

- Kaneko, Y.i; Buesching, C. D.; Newman, C. (2017-04-13). "Japan: Unjustified killing of badgers in Kyushu". Nature. 544 (7649): 161. doi:10.1038/544161a.