Samsun

Samsun (Pontic Greek: Σαμψούντα, Sampsúnta) is a city on the north coast of Turkey with a population of around 1.4 million people. It is the provincial capital of Samsun Province and a major Black Sea port. The growing city has two universities, several hospitals, shopping malls, much light manufacturing industry, sports facilities and an opera.

Samsun | |

|---|---|

In order: Artificial lake near Liberation wharf, Statue of Honor in Belediye Park, Istiklal Street, bottom: View of SS Bandırma museum ship, Samsun tram, wall of covered market. | |

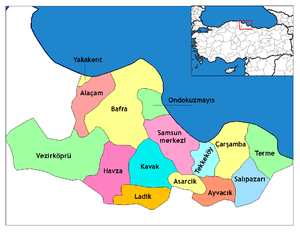

Samsun Location of Samsun within Turkey  Samsun Samsun (Black Sea) | |

| Coordinates: 41°17′25″N 36°20′01″E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Black Sea |

| Province | Samsun |

| Boroughs | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mustafa Demir (AKP) |

| Area | |

| • Metropolitan municipality | 1,055 km2 (407 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 4 m (13 ft) |

| Population (2013) | |

| • Density | 573/km2 (1,480/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 605,319 |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (FET) |

| Postal code | 55 |

| Area code(s) | (+90) 362 |

| Licence plate | 55 |

| Climate | Cfa |

| Website | www.samsun.bel.tr www.samsun.gov.tr |

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk began the Turkish War of Independence here in 1919.

Name

The present name of the city may come from its former Greek name of Amisós (Αμισός) by a reinterpretation of eís Amisón (meaning "to Amisós") and ounta (Greek suffix for place names) to [eí]s Am[p]s-únta (Σαμψούντα : Sampsúnta) and then Samsun[1] (pronounced [samsun]).

The early Greek historian Hecataeus wrote that Amisos was formerly called Enete, the place mentioned in Homer's Iliad. In Book II, Homer says that the ἐνετοί (Enetoi) inhabited Paphlagonia on the southern coast of the Black Sea in the time of the Trojan War (c. 1200 BC). The Paphlagonians are listed among the allies of the Trojans in the war, where their king Pylaemenes and his son Harpalion perished.[2] Strabo mentioned that the inhabitants had disappeared by his time.[3]

It has also been known as Peiraieos by Athenian settlers and even briefly as Pompeiopolis by Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus.[4]

The city was called Simisso by the Genoese and during the Ottoman Empire the present name was written in Ottoman Turkish: صامسون (Ṣāmsūn).

History

Ancient history

.jpg)

Paleolithic artifacts found in the Tekkeköy Caves can be seen in Samsun Archaeology Museum.

The earliest layer excavated of the höyük of Dündartepe revealed a Chalcolithic settlement. Early Bronze Age and Hittite settlements were also found there[5] and at Tekkeköy.

Samsun (then known as Amisos, Greek Αμισός, alternative spelling Amisus) was settled in about 760–750 BC by Ionians from Miletus,[6] who established a flourishing trade relationship with the ancient peoples of Anatolia. The city's ideal combination of fertile ground and shallow waters attracted numerous traders.[7]

Amisus was settled by the Ionian Milesians in the 6th century BC,[8] it is believed that there was significant Greek activity along the coast of the Black Sea, although the archaeological evidence for this is very fragmentary.[9] The only archaeological evidence we have as early as the 6th century is a fragment of wild goat style Greek pottery, in the Louvre.[10]

The city was captured by the Persians in 550 BC and became part of Cappadocia (satrapy).[4] In the 5th century BC, Amisus became a free state and one of the members of the Delian League led by the Athenians;[11] it was then renamed Peiraeus under Pericles.[12] Starting the 3rd century BC the city came under the control of Mithridates I, later founder of the Kingdom of Pontus. The Amisos treasure may have belonged to one of the kings. Tumuli, containing tombs dated between 300 BC and 30 BC, can be seen at Amisos Hill but unfortunately Toraman Tepe was mostly flattened during construction of the 20th century radar base.[13]

The Romans conquered Amisus in 71 BC during the Third Mithridatic War.[14] and Amisus became part of Bithynia et Pontus province. Around 46 BC, during the reign of Julius Caesar, Amisus became the capital of Roman Pontus.[8] From the period of the Second Triumvirate up to Nero, Pontus was ruled by several client kings, as well as one client queen, Pythodorida of Pontus, a granddaughter of Marcus Antonius. From 62 CE it was directly ruled by Roman governors, most famously by Trajan's appointee Pliny. Pliny the Younger's address to the Emperor Trajan in the 1st century CE "By your indulgence, sir, they have the benefit of their own laws," is interpreted by John Boyle Orrery to indicate that the freedoms won for those in Pontus by the Romans was not pure freedom and depended on the generosity of the Roman emperor.[15]

The estimated population of the city around 150 AD is between 20,000 and 25,000 people, classifying it as a relatively large city for that time.[16] The city functioned as the commercial capital for the province of Pontus; beating its rival Sinope (now Sinop) due to its position at the head of the trans-Anatolia highway.[11]

In Late Antiquity, the city became part of the Dioecesis Pontica within the eastern Roman Empire; later still it was part of the Armeniac Theme.[17] Samsun Castle was built on the seaside in 1192, it was demolished between 1909 and 1918.

Early Christianity

.jpg)

Though the roots of the city are Hellenistic,[8] it was also one of the centers of an early Christian congregation.[8] Its function as a commercial metropolis in northern Asia Minor was a contributing factor to enable the spread of Christian influence. As a large port city – the commercial capital of Pontus [18] – travel to and from Christian hotbeds like Jerusalem was not uncommon.[19] According to Josephus, there was large Jewish diaspora in Asia Minor.[20] Given that the early evangelist Christians focused on Jewish diaspora communities, and that the Jewish diaspora in Amisus was a geographically accessible group with a mixed heritage group, it is not surprising that Amisus would be an appealing site for evangelist work. The author of 1 Peter 1:1 addresses the Jewish diaspora of the province of Pontus, along with four other provinces: "Peter, an apostle of Jesus Christ, To God's elect, exiles scattered throughout the provinces of Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia and Bithynia." (Peter 1:1) As Amisus would have been the largest commercial port-city in the province, it is believed certain that the spread of Christianity in the region would have begun there.[20] In the 1st century Pliny the Younger documents accounts of Christians in and around the cities of Pontus.[21] His accounts center on his conflicts with the Christians when he served under the Emperor Trajan and describe early Christian communities, his condemnation of their refusal to renounce their religion, but also describes his tolerance for some Christian practices like Christian charitable societies.[22] Many great early Christian figures had connections to Amisus, including Caesarea Mazaca, Gregory the Illuminator (raised as a Christian from 257 CE when he was brought to Amisus) and Basil the Great (Bishop of the city 330–379 CE).[23]

Christian bishops of Amisus include Antonius, who took part in the Council of Chalcedon in 451; Erythraeus, a signatory of the letter that the bishops of Helenopontus wrote to Emperor Leo I the Thracian after the killing of Patriarch Proterius of Alexandria; the late 6th-century bishop Florus, venerated as a saint in the Greek menologion; and Tiberius, who attended the Third Council of Constantinople (680), Leo, the Second Council of Nicaea (787), and Basilius, the Council of Constantinople of 879. The diocese is no longer mentioned in the Greek Notitiae Episcopatuum after the 15th century and thereafter the city was considered part of the see of Amasea. However, some Greek bishops of the 18th and 19th centuries bore the title of Amisus as titular bishops.[24] In the 13th century the Franciscans had a convent at Amisus, which became a Latin bishopric some time before 1345, when its bishop Paulus was transferred to the recently conquered city of Smyrna and was replaced by the Dominican Benedict, who was followed by an Italian Armenian called Thomas.[25] No longer a residential diocese, it is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.[26]

Medieval and modern history

Samsun was part of the Seljuk Empire,[27] the Sultanate of Rum, the Empire of Trebizond, and was one of the Genoese colonies. After the breakup of the Seljuk Empire into small principalities (beyliks) in the late 13th century, the city was ruled by one of them, the Isfendiyarids. It was captured from the Isfendiyarids at the end of the 14th century by the rival Ottoman beylik (later the Ottoman Empire) under sultan Bayezid I, but was lost again shortly afterwards.

The Ottomans permanently conquered the town in the weeks following 11 August 1420.[28]

In the later Ottoman period, it became part of the Sanjak of Canik (Turkish: Canik Sancağı), which was at first part of the Rûm Eyalet. The land around the town mainly produced tobacco, with its own type being grown in Samsun, the Samsun-Bafra, which the British described as having "small but very aromatic leaves", and commanding a "high price."[29] The town was connected to the railway system in the second half of the 19th century, and tobacco trade boomed. There was a British consulate in the town from 1837 to 1863.[30]

Samsun, then home to an Armenian community numbering over 5,000, was heavily affected during the Armenian Genocide of 1915, the last Armenian Zoroastrians – the Arewordik, or children of the sun, lived there. According to local eyewitnesses, such as Hafiz Mehmet, many of the Samsun Armenians were drowned in the Black Sea.[31] Others were deported from Samsun and ultimately massacred in provinces further south. After the Armenian Genocide, there remained eleven Islamized Armenians and two Armenian physicians. Armenian orphans who had survived were given to Turkish families.[32]

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk established the Turkish national movement against the Allies in Samsun on 19 May 1919, the date which traditionally marks the beginning of the Turkish War of Independence. Atatürk, appointed by the Ottoman government as Inspector of the Ninth Army Troops Inspectorate of the Empire in eastern Anatolia, left Constantinople aboard the now-famous SS Bandırma 16 May for Samsun. Instead of obeying the orders of the Ottoman government, then under the control of the occupying Allies, he and a number of colleagues declared the beginning of the Turkish national movement. As a result of this, the Greek population of Samsun was subject to looting, massacre, and deportation by Turkish irregular groups, as noted by representatives of the American Near East Relief. However these groups couldn't operate freely in Samsun as they did in adjacent region of Merzifon and Bafra due to the presence of the Allied fleet.[33] Being alarmed due to the presence of Greek warships in the vicinity of Samsun, the Turkish national movement undertook the deportation of 21,000 local Greeks to the interior of Anatolia. [34] Later, in early June 1922, the city was bombarded by the Allied navy.

By 1920, Samsun's population totaled about 36,000.[35]

Demographics

During the Tanzimat period and the subsequent wars, Ottoman Muslims were exiled from the Balkans[36] and Circassians were expelled from the Caucasus region.[37] Many of the present inhabitants trace their origins from further west or east on the Black Sea coast. The overwhelming majority of people are Muslims.

Government

The council has various service units.[39] There is a 2010 to 2014 strategic plan.[40] Samsun has a budget deficit of TL 323 million.[41]

Geography

Samsun is a long city which extends along the coast between two river deltas which jut into the Black Sea. It is located at the end of an ancient route from Cappadocia: the Amisos of antiquity lay on the headland northwest of the modern city center.

The city is growing fast: land has been reclaimed from the sea and many more apartment blocks and shopping malls are currently being built. Industry is tending to move (or be moved) east, further away from the city center and towards the airport.

Rivers

To Samsun's west, lies the Kızılırmak ("Red River", the Halys of antiquity), one of the longest rivers in Anatolia and its fertile delta. To the east, lie the Yeşilırmak ("Green River", the Iris of antiquity) and its delta. The River Mert reaches the sea at the city.

Climate

Samsun has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen: Cfa), like most of the eastern Black Sea coast of Turkey.[42]

Spring temperatures can vary by over 10 degrees from one day to the next. Summers are warm and humid, and the average maximum temperature is around 27 °C (81 °F) in August. Winters are cool and damp, and the lowest average minimum temperature is around 3 °C (37 °F) in January.

Precipitation is heaviest in late autumn and early winter. Snow sometimes occurs between the months of December and March, but never more than a few centimeters of snow falls in the city, and temperatures below the freezing point rarely last more than a couple of days.

The water temperature, as in the whole Turkish Black Sea coast, is always cool, fluctuating between 8–20 °C (46–68 °F) throughout the year.

| Climate data for Samsun (1929–2017) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 24.2 (75.6) |

26.5 (79.7) |

33.6 (92.5) |

37.0 (98.6) |

37.4 (99.3) |

37.4 (99.3) |

37.5 (99.5) |

39.0 (102.2) |

38.3 (100.9) |

38.4 (101.1) |

32.4 (90.3) |

28.7 (83.7) |

39.0 (102.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 10.6 (51.1) |

10.9 (51.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

15.2 (59.4) |

19.0 (66.2) |

23.5 (74.3) |

26.4 (79.5) |

27.0 (80.6) |

23.9 (75.0) |

20.2 (68.4) |

16.7 (62.1) |

13.0 (55.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

7.0 (44.6) |

7.9 (46.2) |

11.2 (52.2) |

15.6 (60.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.5 (74.3) |

20.0 (68.0) |

16.2 (61.2) |

12.5 (54.5) |

9.2 (48.6) |

14.5 (58.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4.0 (39.2) |

3.8 (38.8) |

4.5 (40.1) |

7.7 (45.9) |

12.0 (53.6) |

16.1 (61.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

19.6 (67.3) |

16.4 (61.5) |

12.8 (55.0) |

9.2 (48.6) |

6.2 (43.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −8.1 (17.4) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

2.7 (36.9) |

1.9 (35.4) |

13.4 (56.1) |

12.4 (54.3) |

6.8 (44.2) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 70.6 (2.78) |

58.9 (2.32) |

65.8 (2.59) |

57.6 (2.27) |

48.6 (1.91) |

45.3 (1.78) |

34.4 (1.35) |

37.0 (1.46) |

53.8 (2.12) |

78.8 (3.10) |

83.7 (3.30) |

82.1 (3.23) |

716.6 (28.21) |

| Average precipitation days | 13.5 | 13.5 | 15.2 | 13.6 | 12.6 | 9.1 | 5.8 | 6.3 | 9.5 | 11.9 | 11.9 | 12.9 | 135.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 83.7 | 90.4 | 108.5 | 135.0 | 186.0 | 246.0 | 269.7 | 251.1 | 189.0 | 142.6 | 111.0 | 83.7 | 1,896.7 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 2.7 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 6.2 | 8.2 | 8.7 | 8.1 | 6.3 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 5.2 |

| Source: Turkish State Meteorological Service[43] | |||||||||||||

Pollution

Air pollution is a problem in some parts of the city, especially in winter when free coal is supplied to poor families by the government. NOx levels on Yüzüncüyıl Boulevard are among the highest in the country.[44]

Architecture

Mosques

- Pazar Mosque, Samsun's oldest surviving building, a mosque built by the Ilkhanate Mongols in the 13th century.

- Valide or Büyük Mosque was built by Batumlu Hacı Efendi in 1884. Its name "Valide" comes from the mother of Ottoman Sultan Abdulaziz.[45]

- Hacı Hatun Mosque dates from 1694.

Churches

- Samsun Protestant Church

Samsun used to have many Greek Orthodox churches however all got either destroyed or converted to mosques.

Transport

Long distance buses the bus station is outside the city centre, but most bus companies provide a free transfer there if you have a ticket. Passenger and freight trains run to Sivas via Amasya. The train station is in the city center. Freight trains are taken by ferry to railways at Kavkaz in Russia, and will later see service to the port of Varna in Bulgaria and Poti in Georgia.[46]

Modern trams run between the train station and Ondokuz Mayıs University. There is a plan to run electrically powered bus rapid transit between the railway station and Tekkekoy. City buses carry passengers actively. Dolmuş, the routes are numbered 1 to 4 and each route has different color minibuses. The 320 m (1,050 ft) long Samsun Amisos Hill Gondola serves from Batıpark the archaeological area on the Amisos Hill, where ancient tombs in tumuli were discovered.

Samsun-Çarşamba Airport is 23 km (14 mi) east of the city center. It is possible to reach the airport by Havas service buses: they depart from the coach park close to Kultur Sarayi in the city center.[47] Horse-drawn carriages, (Turkish:fayton) run along the seafront. There was automated bike rental along the seafront, but it is not currently operational.

Economy

Samsun has a mixed economy[48] with a cluster of medical industries.[49]

Ports and shipbuilding

Samsun is a port city. In the early 20th century, the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey funded the building of a harbor. Before the building of the harbor, ships had to anchor to deliver goods, approximately 1 mile or more from shore. Trade and transportation was focused around a road to and from Sivas.[35] The privately operated port fronting the city centre handles freight, including RORO ferries to Novorossiysk, whereas fishing boats land their catches in a separate harbour slightly further east. A ship building yard is under construction at the eastern city limit. Road and rail freight connections with central Anatolia can be used to send inland both the agricultural produce of the surrounding well rained upon and fertile land, and also imports from overseas.

Coal imports from Donbass

Donbass anthracite, imported via the Russian ports of Azov and Taganrog, is said to be illegally exported Ukrainian coal.[50] In 2019 some crew were rescued but 6 died after a ship sank in the Black Sea.[51]

Manufacturing and food processing

There is a light industrial zone between the city and the airport. The main manufactured products are medical devices and products, furniture (wood is imported across the Black Sea), tobacco products (although tobacco farming is now limited by the government), chemicals and automobile spare parts.

Flour mills import wheat from Ukraine and export some of the flour.

Local government and services

Provincial government and services (e.g. courts, prisons and hospitals) support the surrounding region. Agricultural research establishments support provincial agriculture and food processing.

Shopping

Most of the many new shopping malls are purpose built, but the former tobacco factory in the city center has been converted into a mall.

Culture

The Atatürk Culture Center

Atatürk Kültür Sarayı (AKM – Palace of Culture). Concerts and other performances are held at the Kultur Sarayi, which is shaped much like a ski jump. "Samsun State Opera and Ballet" performs in The Atatürk Culture Center. Founded in 2009 it is one of the six state opera houses in Turkey. The Samsun Opera have performed Die Entführung (W. A. Mozart) in the annual Istanbul Opera Festival. In collaboration with The Pekin Opera, The Samsun Opera performed Puccini's Madama Butterfly in the Aspendos International Opera and Ballet Festival in 2012. Other performances include La bohème, La traviata, Don Quijote, Giselle. The current musical director is Lorenzo Castriota Skanderbeg.

Museums

- Archaeological and Atatürk Museum. The archaeological part of the museum displays ancient artifacts found in the Samsun area, including the Amisos treasure. The Atatürk section includes photographs of his life and some personal belongings.

- Atatürk (Gazi) Museum. It houses Atatürk's bedroom, his study and conference room as well as some personal belongings.

- Samsun City Museum. A new museum.

Folk dancing

There is an annual international festival.[52]

Education

There are two universities in Samsun: the state run Ondokuz Mayıs University and the private sector Canik Başarı University. There is also a police training college[53] and many small private colleges.

Parks, nature reserves and other greenspace

- Parks

- Batı Park (West Park) is a large park on land reclaimed from the sea

- Doğu Park (East Park)

- Atatürk Park contains his statue by Austrian sculptor Heinrich Krippel, which was completed in 1931. The statue was depicted on the obverse of the Turkish 100,000 lira banknotes of 1991–2001.[54]

- Nature reserves

- Çakırlar Korusu[55]

- Other greenspace

There are several army bases in the city (Esentepe Kışlası, Gökberk Kışlası, 19 Mayis Kışlası and others). Should they become surplus to military requirements in future, for example due to reduced conscription in Turkey, it is currently unclear whether they would become urban open space or be further built on.

Sports

In ancient Roman times gladiator sword fighting[56] apparently took place in Amisos, as depicted on a tombstone dating from the 2nd or 3rd century CE.

Tekkeköy Yaşar Doğu Arena opened in 2013.

Football is the most popular sport: in the older districts above the city center children often kick balls around in the evenings in the smallest streets. The city's football club is Samsunspor, which plays its games at the Samsun 19 Mayıs Stadium.

Basketball, volleyball, tennis, swimming, cable skiing (in summer), horse riding, go karting, paintballing, martial arts and many other sports are played. Cycling and jogging are only common along the sea front, where recreational fishing is also popular.

International relations

Twin towns—Sister cities

Samsun is twinned with:

Notable people

- Mehmet Aslantuğ, actor

- A. I. Bezzerides (1908–2007), American novelist and screenwriter of Greek and Armenian descent

- Nebahat Çehre, actress and beauty queen

- Yıldıray Çınar, musician

- Tanju Çolak, 1987 European Golden Boot holder soccer player/striker

- Mustafa Dağıstanlı, two-time Olympic gold medalist sports wrestler

- Yaşar Doğu, gold medalist wrestler

- Xenophon Akoglou, Greek author, folklorist, soldier and writer

- Ece Erken, TV hostess and actress

- Orhan Gencebay, musician

- DJ Jackson, DJ

- Sagopa Kajmer, musician

- Deniz Kılıçlı, college basketball player at West Virginia University

- Şefik Avni Özüdoğru, military officer in the Ottoman and Turkish armies

- Baki Sarısakal, historian

- Ahu Türkpençe, actress

- Tyrannion of Amisus, 1st century BC grammarian

See also

- Anatolian Tigers

- Beyliks of Canik

- State road D010 (Turkey)

- Samsun Castle

- Category:Tourist attractions in Samsun

References

- Özhan Öztürk. Karadeniz: Ansiklopedik Sözlük (Blacksea: Encyclopedic Dictionary) Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. 2 Cilt (2 Volumes). Heyamola Publishing. Istanbul. 2005 ISBN 975-6121-00-9

- Homer, Iliad; online version at classics.mit.edu, accessed on 2009-08-18. Book II: "The Paphlagonians were commanded by stout-hearted Pylaemanes from Enetae, where the mules run wild in herds. These were they that held Cytorus and the country round Sesamus, with the cities by the river Parthenius, Cromna, Aegialus, and lofty Erithini."

- Strab. 12.3 "Tieium is a town that has nothing worthy of mention except that Philetaerus, the founder of the family of Attalic Kings, was from there. Then comes the Parthenius River, which flows through flowery districts and on this account came by its name; it has its sources in Paphlagonia itself. And then comes Paphlagonia and the Eneti. Writers question whom the poet means by 'the Eneti,' when he says, 'And the rugged heart of Pylaemenes led the Paphlagonians, from the land of the Eneti, whence the breed of wild mules; for at the present time, they say, there are no Eneti to be seen in Paphlagonia, though some say that there is a village on the Aegialus ten schoeni distant from Amastris.' But Zenodotus writes 'from Enete,' and says that Homer clearly indicates the Amisus of today. And others say that a tribe called Eneti, bordering on the Cappadocians, made an expedition with the Cimmerians and then were driven out to the Adriatic Sea. But the thing upon which there is general agreement is, that the Eneti, to whom Pylaemenes belonged, were the most notable tribe of the Paphlagonians, and that, furthermore, these made the expedition with him in very great numbers, but, losing their leader, crossed over to Thrace after the capture of Troy, and on their wanderings went to the Enetian country, as it is now called. According to some writers, Antenor and his children took part in this expedition and settled at the recess of the Adriatic, as mentioned by me in my account of Italy. It is therefore reasonable to suppose that it was on this account that the Eneti disappeared and are not to be seen in Paphlagonia."

- "Samsun Guide" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2014.

- "..:: REPUBLIC OF TURKEY MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND TOURISM ::." Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- "..:: REPUBLIC OF TURKEY MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND TOURISM ::." Archived from the original on 4 April 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- {Cohen, Getzel M. (1995). "The Hellenistic Settlements in Europe, the Islands, and Asia Minor". Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. p. 384.

- Wilson, M. W. "Cities of God in Northern Asia Minor: Using Stark's Social Theories to Reconstruct Peter's Communities". Verbum et Ecclesia 32 (1). p. 3.

- Topalidis, S. "Formation of the First Greek Settlements in the Pontos". Pontos World. Pontosworld.com. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- Tsetskhladze, G.R. (1998 ) "The Greek Colonisation of the Black Sea Area: Historical Interpretation of Archaeology". Stuttgart: F. Steiner. p. 19.; Louvre page Archived 23 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Wilson, M. W. "Cities of God in Northern Asia Minor: Using Stark's Social Theories to Reconstruct Peter's Communities". Verbum et Ecclesia 32 (1). p. 4.

- Jones, A.H.M (1937). "The Cities of the Eastern Roman Provinces". Oxford: The Carendon Press. p. 149.

- "ESKİ SAMSUN' DA (AMİSOS) AYDINLANAN TARİH". Archived from the original on 30 October 2014.

- "Antik Amisos Kenti". Archived from the original on 30 March 2014.

- Orrery, J. B. (1752). "The Letters of Pliny the Younger: With Observations on Each Letter; and an Essay on Pliny's Life, Addressed to Charles Lord Boyle". The 3rd ed. London: Printed by James Bettenham, for Paul Vaillant. p. 407.

- Mitchell, S. (1995). "Anatolia: Land, Men, and Gods in Asia Minor". Journal of Roman Studies, 85. pp. 301–302.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies. (2013). "Roads to Pontus, Royal and Roman." The Journal of Hellenic Studies (Vol. 21). London: Forgotten Books. (Original work published pre-1945, year unknown) p. 105-6.

- Wilson, M. W. "Cities of God in Northern Asia Minor: Using Stark's Social Theories to Reconstruct Peter's Communities". Verbum et Ecclesia 32 (1). p. 2.

- Schalit, A. "Asia Minor." Encyclopedia Judaica. Accessed 11 March 2015.

- "Pliny and Trajan on the Christians." Pliny and Trajan on the Christians. Accessed 7 April 2015.

- Alikin, V. A. (2010). 'Chapter 7.' In The Earliest History of the Christian Gathering: Origin, Development and Content of the Christian Gathering in the First to Third Centuries. Leiden: Brill. p. 270.

- Wilson, M. W. "Cities of God in Northern Asia Minor: Using Stark's Social Theories to Reconstruct Peter's Communities". Verbum et Ecclesia 32 (1). p. 7.

- Siméon Vailhé, v. Amisus, in Dictionnaire d'Histoire et de Géographie ecclésiastiques Archived 9 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, vol. XII, Paris 1953, coll. 1289–1290]

- Jean Richard, La Papauté et les missions d'Orient au Moyen Age (XIII-XV siècles), École Française de Rome, 1977, pp. 170–171 and 235–236

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 831

- "File:Anatolia 1097 it.svg". Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- Zehiroğlu, A.M. (2018) "Trabzon İmparatorluğu" vol.III pp.150–156 ISBN 978-6058103207

- Prothero, W.G. (1920). Armenia and Kurdistan. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 61. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013.

- "Foreign Office: Consulate, Samsun, Ottoman Empire: Entry Books and Registers of Correspondence". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2006). Turkey Beyond Nationalism Towards Post-Nationalist Identities. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. p. 111. ISBN 085771757X.

- Kevorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. I.B.Tauris. pp. 487–91. ISBN 0857730207.

- Prott, Volker (2016). The Politics of Self-Determination: Remaking Territories and National Identities in Europe, 1917–1923. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191083556.

They lotted and burned the houses of the Greeks... In early June, Hosford continued, Samsun faced the same threat of looting, massacres and deportation... Osman Aga's troops could not operate freely in Samsoun as they did later in Marsovan or had done before in the district of Bafra

- Bartrop, Paul R. (2014). Encountering Genocide: Personal Accounts from Victims, Perpetrators, and Witnesses. ABC-CLIO. p. 64. ISBN 9781610693318.

- Prothero, W.G. (1920). Armenia and Kurdistan. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 54. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013.

- "The Exiles from Balkans to Black Sea Coast After the Tanzimat". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- "Report to the Board of Health of the Ottoman Empire, Samsun, May 20, 1864". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/UstMenu.do?metod=temelist

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 23 November 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "İstanbul, Ankara contribute 60 pct of tax revenue in Q1". TodaysZaman. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- "Climate: Samsun – Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". 31 August 2013. Climate-Data.org. Archived from the original on 6 October 2013.

- "Resmi İstatistikler: İllerimize Ait Genel İstatistik Verileri" (in Turkish). Turkish State Meteorological Service. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- "COBENEFITS Study Turkey" (PDF).

- "Samsun". Archived from the original on 20 May 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- "Samsun-Kavkaz ferry line to link Turkey with Russia, Central Asia". Archived from the original on 19 April 2014.

- "Samsun". Archived from the original on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- "..:: REPUBLIC OF TURKEY MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND TOURISM ::." Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- "2023 Export Target 5 Billion Dollars". Archived from the original on 8 March 2014.

- "Russia's Hybrid Strategy in the Sea of Azov: Divide and Antagonize (Part Two)". Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 16 Issue: 18. Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- "Cargo ship sinks off Turkey's Black Sea coast; 6 dead". Associated Press. 7 January 2019.

- ""FESTİVALİ ANLAMAK" ve SAHİP". Archived from the original on 21 February 2014.

- "Police college website (Turkish)". Archived from the original on 14 September 2012.

- Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Archived 3 June 2009 at WebCite. Banknote Museum: 7. Emission Group – One Hundred Thousand Turkish Lira – I. Series Archived 22 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine, II. Series Archived 22 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine & III. Series Archived 22 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine. – Retrieved on 20 April 2009.

- "ÇAKIRLAR KORUSUMESİRE YERİ". Archived from the original on 5 November 2014.

- "Tombstone for the gladiator Diodorus". Archived from the original on 17 February 2014.

- "Samsun – Twin Towns". Samsun-City.sk. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Samsun. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Samsun. |

- Samsun Governor's Office (in Turkish)

- Samsun Metropolitan Municipality (in Turkish)

- Official Tourist Information

- Port Authority

- Current port arrivals and departures

- Coins—Amisus coins (click "Database" and search by state: Amisus)

- Amisos coins found on criminals

- Map of Samsun

- Opera and Ballet

- A History of Amisos (Samsun)

- Samsun Business (in Turkish)

.jpg)